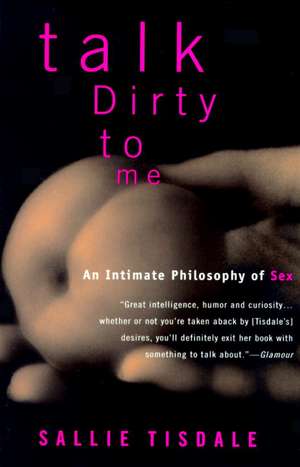

Talk Dirty to Me

Autor Sallie Tisdaleen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 1995

Sallie Tisdale shuns the dry style of academics and takes us on a journey through gender and desire, romance and pornography, prostitution and morality, fantasies and orgasm. She guides us through her field research of peep shows, XXX stores, and even the pornography collection of the British Library. Interweaving her own personal feelings, experiences, and revelations, she presents a brilliant, fascinating, and wholly original portrait of sex and sexuality in America, while encouraging us to explore and create our own "intimate philosophies."

Preț: 108.09 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 162

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.68€ • 21.65$ • 17.21£

20.68€ • 21.65$ • 17.21£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 10-24 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385468558

ISBN-10: 0385468555

Pagini: 366

Dimensiuni: 133 x 206 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0385468555

Pagini: 366

Dimensiuni: 133 x 206 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Extras

We talk about sex all the time, we moderns. We see sex all the time--raw, explicit images everywhere we look. There is "sex" in the media and "sex" in our culture; we argue over "sex education" and discuss our "sexual disorders." But "sex" always seemed less concrete than this to me, more disobedient. Sex troubled me--troubled me in proportion to how much I tried over the years to separate sex from the rest of my life, to manage and define it, to speak of sex as something that began, ended, lived separately from me. Sex demanded my close attention even when I would have preferred to attend to almost anything else.

Devilish reminders crop up all the time. The planet itself is laden with sex, marbled with my physical and psychic responses to its parts, made out of my relationship with its skin. How we are rooted to the earth through our bodies determines how we see other bodies, and ultimately the earth itself. This seems obvious, and yet we don't call this sex. To do so makes sex awfully big, but big is exactly what sex is. Freud was never more right than when he called the human animal "polymorphously perverse." To the unschooled body there are no good or bad sexual objects, no right or wrong responses. (Even the schooled body gets confused.) Sexual acts are one of the primary means by which we can act out our inarticulated inner lives.

The Latin root for pudenda, our genitals, means "to be ashamed." We are twisted between this and the body's blessed pleasures, living among a proliferation of sexual images even as we live in shame. The sex that is presented to us in everyday culture feels strange to me; its images are fragments, lifeless, removed from normal experience. Real sex, the sex in our cells and in the space between our neurons, leaks out and gets into things and stains our vision and colors our lives. This is what we can't see. This is what we never say.

The question is transparent: Why are we so unhappy about our own sexual acts and the acts of others?

There is a school of thought--two schools, in fact--that holds sex to be simply dangerous. The cosmic schools which includes a fair amount of our religious instruction, sees sex as a natural force that must be allowed to exist only within certain absolute bounds. A related philosophy holds that sex as we know it is politically and socially unpalatable. This is most publicly presented by the conservative feminist dictum that in a sexist culture, sex hurts women and no woman lives a sexually free life until the culture itself is uprooted. These beliefs have seeds of truth in them, as does the idea--less a belief than a feeling--that sex is too intimate for public discourse. A different standard is applied to sex this way, a standard that removes it from any context but its most immediate one.

Each of us finds sexual censure in our individual lives, of one kind or another. As for myself, I've been struck (shamed) by highhandedness--the faintly damning gentility of the auteurs. Sex in this view lacks aesthetic; it's seen as a rather low pursuit--fun, but not exactly Ivy League. Sex invokes a kind of hindbrain howling in most people now and then, and because of this--in spite of this, perhaps--the auteur says humans should rise above their baser natures. People must seek the refined and the complex and intellectual in the world, should create, beautify, compose. Presumably art would be considered a more complex, symbolic, and layered act. But good sex is a symphony of experiences infinitely complicated with meaning, rich and unpredictable, as capable of disturbing and illuminating the individual as any formal work of art, as memorable, as fleeting. The real point being made is that sex is low because it's universal. After all, any chimp can fling paint.

Virtually all serious conversation about sex is sooner or later dismissed as trivial--as being too small. In the grand scheme of things sex is nothing beside the more publicly applauded accomplishments. Sex is the ultimate ephemera, a phantom. But our culturewide aversion makes sex more, not less, real. Refusing to look at an illusion gives an illusion body and strength, gives it power. If you want to make a mirage go away, walk toward it. If you turn and run, the lake gets bigger and the palm trees more inviting every time you look back. Sex is, truly, not important--that is, something we can cease worrying about--only to the extent that we look at sex and see it for what it really is, and nothing more.

Sex is as important, in much the same way and to about the same degree, as what we eat and how we sleep. Sex is important because it is central to being human, because it intersects everything else, because it is the physical realm's metaphor for the chaos and texture of our spiritual and psychological lives. Sex is a kind of intuitive art in itself, an art made largely by the human body on levels our frontal cortex can only partly imagine. Sex, in the end, doesn't matter as much as how we treat each other--how much respect and care we accord each other, ourselves, our place, and whatever we call God. What fascinates me most about sex is how many ways we--and I--have used the fear of sex to justify disrespect, castigation, condemnation, and destruction of all these things, including God.

Sex changes the way we see ourselves, breaking and remaking the boundaries of the body and of relationships. It's a door that swings only one way, preventing return. Sex turns us literally inside out, molds and subverts fundamental assumptions. Sex has a unique ability in the human realm to both brutalize and comfort the individual. Turning away from sex means turning away from ourselves, turning away others; fear of sex means fear of others. Without crossing through the country of sex, there's a lot of other territory we can't begin to traverse.

But then again. The first time I had sex--with forethought and contraception and careful planning--all I could say was, "Is that all?" My poor partner, years older than me but still naive about anatomy, could only nod. Was that really what all the fuss was about? I wondered. Was that what my parents did, what happened in the movies when the lights went out, was that momentary shiver the Sturm und Drang of eons? I felt a little . . . disappointed.

I grew up, in the late sixties and early seventies, into the kind of young feminist who believed in the agenda of equality without having read much of the theory. I learned the lingo, talked the talk, walked the walk a little bit. But my secret sexual fantasies seemed to wiggle free of my politics no matter what, seemed to expand and sometimes explode into my manifestly unfeminist consciousness. Part of the feminist agenda, I believed, was raising my own and other people's consciousnesses to the point where images of heterosexual oppression and traditional roles simply disappeared. Therefore, my sexual fantasies would be reeducated along with my relationships and language. But even reading feminist theory didn't help that. Parts of my consciousness refused to rise, staying far below the sanitized plain of social politics.

I didn't even know the words for some of what happened in my sexual fantasies, but I was sure of one thing. Liberated women, women who had thrown off the yoke of heterosexism, didn't even think about what I wanted to do. I wasn't ashamed of being preoccupied with sex--everyone I knew was preoccupied with sex, one way or the other. And though I was plenty confused by the messy etiquette of the early 1970s, and spent time wondering just how much shifting of partners I should do, that was more a source of embarrassed bumbling than conscious shame. The Amazon and Earth Mother images of 1970s-era feminism did me a world of good, in fact. I felt it was okay to have sex, to be sexual--as long I was sexual in a wholesome, Earth Mother kind of way. I felt a little work-ethic guilt at times, since I'd absorbed the solid lower-middle-class belief that whatever was fun didn't count as work, and sex, for all its drama, was sometimes quite a lot of fun. But I was also ashamed, simply ashamed of my own unasked-for appetites and shockingly incorrect fantasies, which would not be still, and which seemed to violate the hygienic dogma of sexual equality and Amazon health.

Sex is so often examined within marriage and relationship, one could almost imagine that's the only place sex exists. I want to deliberately examine sex outside the structure of long-term relationships because the psychic experience of sex doesn't stop at the edge of the relationship even if the physical acts of sex do. In other words, even if I am monogamous for life, my sexuality is promiscuous--roving and polyfidelitous and amoral. If we pretend our sexual feelings always occur (or only rightly can occur) inside the bounds of a commitment, we are lying to ourselves. Even within these bounds, sex takes many forms. In a way, it's unfortunate that we use this one three- letter word to refer to the incredible range of erotic behavior of which people are capable. Just for myself, I would say the best sex I've had and the worst sex I've had don't belong in the same box at all, can't be discussed with the same vocabulary, described in the same language. It's not quite fair to talk about sex in any general way at all.

Love can coexist with, and join, everything I'm talking about. I've learned more about sex through the tunnels of love than otherwise, by far. Sexual passion greatly complicates but also greatly expands the already labyrinthine complications of love itself. With sexual love can come moments of overpowering fulfillment, an almost devastating, a frightening, satiety. But even in a long-term romance there is a world of difference between the desire for the lover's body and the desire for the lover's body, and for now, this last is what concerns me.

Most sex research is touched by a slight whiff of erotophobia, written dryly and pedantically, tainted by what Kenneth Tynan once called the "whiff of evasiveness." When literary critics do deign to discuss sex, they pinch their prose up into tight knots, lest anyone think they were aroused by their subject. Unlike, say, particle physics or eighteenth- century landscape styles, the erotic as a study causes its students to repress and contain their enthusiasm. They must be careful not to wax too pleased. A surprising amount of intellectual material on sex discusses the subject as though it were a form of garbage, interesting in an anthropological way for all it says about the culture that makes it, but unpalatable nonetheless.

Over the years I've read a lot of the research and I've read theory and I've read plenty of mannerly and overblown literary prose on the subject, but what I really longed for all along was material that addressed the real experience of sex. My own study has never been an intellectual exercise even when I wanted it to be, even when I knew exactly why so many scholars write as though they have never had a sexual thought. Sex has always been, and remains, intensely emotional and socially powerful for me. Studying it was part of my reconciliation with a large and demanding aspect of my life. The most important part of that reconciliation is understanding just how individualistic sex is. I see how much pain people can feel around the subject of sex, how injured and afraid of sex a lot of people are--how injured I am in certain ways. I can see why people sometimes want so much to avoid the topic, why other people seem unable to avoid it. Either way, sex counts.

This book, even when it's about other people's fantasies and other people's myths, is largely about me. It has to be. These are my concerns, my interests, my own little fetishes, as it were. This behavior that is so much a part of our community and personal relations is very much a behavior of the single, lone self. All I've read of sex in history, in anthropology, in religion, in other people's lives, I've read more for my own reassurance, to assuage my own guilt and clear up my confusion than for anything else. And I've been reassured.

In February 1992 I published an essay in Harper's about my interest in pornography. It was the first time I'd written transparently about sex and its complicated, layered meanings. Pornography is a hall of mirrors, a central symbol of the society-wide confusion over sex. By its existence, porn defines us as sexual animals; its only function is to arouse our primal sexual response. The urge (which I certainly felt) to discuss pornography in solely cerebral or political terms seemed, in the end, to be useless as well as silly. Pornography is designed to bypass the brain as much as possible. I was interested in the discomfort pornography brings up, both for others and for myself; no matter what else I could say about it, I had to admit that I found a lot of pornography exciting. It got me, down deep, and I could think of no better unifying metaphor for the impact of sex on my life. Sex has eternal charm for the body--a perpetual, organic hold. Porn is sex off the leash.

I received a lot of letters in response to that essay--a few dozen canceled subscriptions, a lot of thoughtful letters from women and men who had struggled to understand their own interest in pornography, a few huzzahs, a few mash notes, a few bare confessions. One woman wrote to say I should not be allowed to have children, failing to explain where her own children had come from. It's difficult for any of us to talk honestly and seriously about sex, and it may be especially hard for men to listen to anyone, male or female, talk about sex. One man wrote offering to cut his penis off and mail it to me. A radio interviewer in Canada asked me to describe what I was wearing, and then, please, to "talk dirty" to him.

Several letter writers who identified themselves as conservative feminists relied more on epithet than analysis; their insults were graphic and vile. I was struck by their rage, their venom, which was so much greater than the reservations I had expressed in the essay about the conservative feminist position on pornography. Their rage, in fact, was considerably greater and more personally expressed than that of the subscription-cancelers. That group was interesting largely because they equated my frank discussion of pornography with pornography itself. (Censorship, legal and otherwise, makes it impossible not only to talk about the censored object, but about censorship.) There was clearly something much deeper than a political disagreement going on.

Sometimes I'm shocked at what shocks, the cultural relativism at work. The sculptures of Pompeii shocked the Europe of the 1700s, Kinsey shocked Americans in the 1940s, and Shakespeare shocks us now. Our oldest stories validate desire. I sometimes wish that those who rail about morality and normality would read a little anthropology and a bit of Homer. Myths and folklore are full of blunt, amused, and salacious stories, full of castration and masturbation and incest, necrophilia and zoophilia, the mysterious power of the vagina and the clitoris. Many cultures have practiced freer and more open sex l

Devilish reminders crop up all the time. The planet itself is laden with sex, marbled with my physical and psychic responses to its parts, made out of my relationship with its skin. How we are rooted to the earth through our bodies determines how we see other bodies, and ultimately the earth itself. This seems obvious, and yet we don't call this sex. To do so makes sex awfully big, but big is exactly what sex is. Freud was never more right than when he called the human animal "polymorphously perverse." To the unschooled body there are no good or bad sexual objects, no right or wrong responses. (Even the schooled body gets confused.) Sexual acts are one of the primary means by which we can act out our inarticulated inner lives.

The Latin root for pudenda, our genitals, means "to be ashamed." We are twisted between this and the body's blessed pleasures, living among a proliferation of sexual images even as we live in shame. The sex that is presented to us in everyday culture feels strange to me; its images are fragments, lifeless, removed from normal experience. Real sex, the sex in our cells and in the space between our neurons, leaks out and gets into things and stains our vision and colors our lives. This is what we can't see. This is what we never say.

The question is transparent: Why are we so unhappy about our own sexual acts and the acts of others?

There is a school of thought--two schools, in fact--that holds sex to be simply dangerous. The cosmic schools which includes a fair amount of our religious instruction, sees sex as a natural force that must be allowed to exist only within certain absolute bounds. A related philosophy holds that sex as we know it is politically and socially unpalatable. This is most publicly presented by the conservative feminist dictum that in a sexist culture, sex hurts women and no woman lives a sexually free life until the culture itself is uprooted. These beliefs have seeds of truth in them, as does the idea--less a belief than a feeling--that sex is too intimate for public discourse. A different standard is applied to sex this way, a standard that removes it from any context but its most immediate one.

Each of us finds sexual censure in our individual lives, of one kind or another. As for myself, I've been struck (shamed) by highhandedness--the faintly damning gentility of the auteurs. Sex in this view lacks aesthetic; it's seen as a rather low pursuit--fun, but not exactly Ivy League. Sex invokes a kind of hindbrain howling in most people now and then, and because of this--in spite of this, perhaps--the auteur says humans should rise above their baser natures. People must seek the refined and the complex and intellectual in the world, should create, beautify, compose. Presumably art would be considered a more complex, symbolic, and layered act. But good sex is a symphony of experiences infinitely complicated with meaning, rich and unpredictable, as capable of disturbing and illuminating the individual as any formal work of art, as memorable, as fleeting. The real point being made is that sex is low because it's universal. After all, any chimp can fling paint.

Virtually all serious conversation about sex is sooner or later dismissed as trivial--as being too small. In the grand scheme of things sex is nothing beside the more publicly applauded accomplishments. Sex is the ultimate ephemera, a phantom. But our culturewide aversion makes sex more, not less, real. Refusing to look at an illusion gives an illusion body and strength, gives it power. If you want to make a mirage go away, walk toward it. If you turn and run, the lake gets bigger and the palm trees more inviting every time you look back. Sex is, truly, not important--that is, something we can cease worrying about--only to the extent that we look at sex and see it for what it really is, and nothing more.

Sex is as important, in much the same way and to about the same degree, as what we eat and how we sleep. Sex is important because it is central to being human, because it intersects everything else, because it is the physical realm's metaphor for the chaos and texture of our spiritual and psychological lives. Sex is a kind of intuitive art in itself, an art made largely by the human body on levels our frontal cortex can only partly imagine. Sex, in the end, doesn't matter as much as how we treat each other--how much respect and care we accord each other, ourselves, our place, and whatever we call God. What fascinates me most about sex is how many ways we--and I--have used the fear of sex to justify disrespect, castigation, condemnation, and destruction of all these things, including God.

Sex changes the way we see ourselves, breaking and remaking the boundaries of the body and of relationships. It's a door that swings only one way, preventing return. Sex turns us literally inside out, molds and subverts fundamental assumptions. Sex has a unique ability in the human realm to both brutalize and comfort the individual. Turning away from sex means turning away from ourselves, turning away others; fear of sex means fear of others. Without crossing through the country of sex, there's a lot of other territory we can't begin to traverse.

But then again. The first time I had sex--with forethought and contraception and careful planning--all I could say was, "Is that all?" My poor partner, years older than me but still naive about anatomy, could only nod. Was that really what all the fuss was about? I wondered. Was that what my parents did, what happened in the movies when the lights went out, was that momentary shiver the Sturm und Drang of eons? I felt a little . . . disappointed.

I grew up, in the late sixties and early seventies, into the kind of young feminist who believed in the agenda of equality without having read much of the theory. I learned the lingo, talked the talk, walked the walk a little bit. But my secret sexual fantasies seemed to wiggle free of my politics no matter what, seemed to expand and sometimes explode into my manifestly unfeminist consciousness. Part of the feminist agenda, I believed, was raising my own and other people's consciousnesses to the point where images of heterosexual oppression and traditional roles simply disappeared. Therefore, my sexual fantasies would be reeducated along with my relationships and language. But even reading feminist theory didn't help that. Parts of my consciousness refused to rise, staying far below the sanitized plain of social politics.

I didn't even know the words for some of what happened in my sexual fantasies, but I was sure of one thing. Liberated women, women who had thrown off the yoke of heterosexism, didn't even think about what I wanted to do. I wasn't ashamed of being preoccupied with sex--everyone I knew was preoccupied with sex, one way or the other. And though I was plenty confused by the messy etiquette of the early 1970s, and spent time wondering just how much shifting of partners I should do, that was more a source of embarrassed bumbling than conscious shame. The Amazon and Earth Mother images of 1970s-era feminism did me a world of good, in fact. I felt it was okay to have sex, to be sexual--as long I was sexual in a wholesome, Earth Mother kind of way. I felt a little work-ethic guilt at times, since I'd absorbed the solid lower-middle-class belief that whatever was fun didn't count as work, and sex, for all its drama, was sometimes quite a lot of fun. But I was also ashamed, simply ashamed of my own unasked-for appetites and shockingly incorrect fantasies, which would not be still, and which seemed to violate the hygienic dogma of sexual equality and Amazon health.

Sex is so often examined within marriage and relationship, one could almost imagine that's the only place sex exists. I want to deliberately examine sex outside the structure of long-term relationships because the psychic experience of sex doesn't stop at the edge of the relationship even if the physical acts of sex do. In other words, even if I am monogamous for life, my sexuality is promiscuous--roving and polyfidelitous and amoral. If we pretend our sexual feelings always occur (or only rightly can occur) inside the bounds of a commitment, we are lying to ourselves. Even within these bounds, sex takes many forms. In a way, it's unfortunate that we use this one three- letter word to refer to the incredible range of erotic behavior of which people are capable. Just for myself, I would say the best sex I've had and the worst sex I've had don't belong in the same box at all, can't be discussed with the same vocabulary, described in the same language. It's not quite fair to talk about sex in any general way at all.

Love can coexist with, and join, everything I'm talking about. I've learned more about sex through the tunnels of love than otherwise, by far. Sexual passion greatly complicates but also greatly expands the already labyrinthine complications of love itself. With sexual love can come moments of overpowering fulfillment, an almost devastating, a frightening, satiety. But even in a long-term romance there is a world of difference between the desire for the lover's body and the desire for the lover's body, and for now, this last is what concerns me.

Most sex research is touched by a slight whiff of erotophobia, written dryly and pedantically, tainted by what Kenneth Tynan once called the "whiff of evasiveness." When literary critics do deign to discuss sex, they pinch their prose up into tight knots, lest anyone think they were aroused by their subject. Unlike, say, particle physics or eighteenth- century landscape styles, the erotic as a study causes its students to repress and contain their enthusiasm. They must be careful not to wax too pleased. A surprising amount of intellectual material on sex discusses the subject as though it were a form of garbage, interesting in an anthropological way for all it says about the culture that makes it, but unpalatable nonetheless.

Over the years I've read a lot of the research and I've read theory and I've read plenty of mannerly and overblown literary prose on the subject, but what I really longed for all along was material that addressed the real experience of sex. My own study has never been an intellectual exercise even when I wanted it to be, even when I knew exactly why so many scholars write as though they have never had a sexual thought. Sex has always been, and remains, intensely emotional and socially powerful for me. Studying it was part of my reconciliation with a large and demanding aspect of my life. The most important part of that reconciliation is understanding just how individualistic sex is. I see how much pain people can feel around the subject of sex, how injured and afraid of sex a lot of people are--how injured I am in certain ways. I can see why people sometimes want so much to avoid the topic, why other people seem unable to avoid it. Either way, sex counts.

This book, even when it's about other people's fantasies and other people's myths, is largely about me. It has to be. These are my concerns, my interests, my own little fetishes, as it were. This behavior that is so much a part of our community and personal relations is very much a behavior of the single, lone self. All I've read of sex in history, in anthropology, in religion, in other people's lives, I've read more for my own reassurance, to assuage my own guilt and clear up my confusion than for anything else. And I've been reassured.

In February 1992 I published an essay in Harper's about my interest in pornography. It was the first time I'd written transparently about sex and its complicated, layered meanings. Pornography is a hall of mirrors, a central symbol of the society-wide confusion over sex. By its existence, porn defines us as sexual animals; its only function is to arouse our primal sexual response. The urge (which I certainly felt) to discuss pornography in solely cerebral or political terms seemed, in the end, to be useless as well as silly. Pornography is designed to bypass the brain as much as possible. I was interested in the discomfort pornography brings up, both for others and for myself; no matter what else I could say about it, I had to admit that I found a lot of pornography exciting. It got me, down deep, and I could think of no better unifying metaphor for the impact of sex on my life. Sex has eternal charm for the body--a perpetual, organic hold. Porn is sex off the leash.

I received a lot of letters in response to that essay--a few dozen canceled subscriptions, a lot of thoughtful letters from women and men who had struggled to understand their own interest in pornography, a few huzzahs, a few mash notes, a few bare confessions. One woman wrote to say I should not be allowed to have children, failing to explain where her own children had come from. It's difficult for any of us to talk honestly and seriously about sex, and it may be especially hard for men to listen to anyone, male or female, talk about sex. One man wrote offering to cut his penis off and mail it to me. A radio interviewer in Canada asked me to describe what I was wearing, and then, please, to "talk dirty" to him.

Several letter writers who identified themselves as conservative feminists relied more on epithet than analysis; their insults were graphic and vile. I was struck by their rage, their venom, which was so much greater than the reservations I had expressed in the essay about the conservative feminist position on pornography. Their rage, in fact, was considerably greater and more personally expressed than that of the subscription-cancelers. That group was interesting largely because they equated my frank discussion of pornography with pornography itself. (Censorship, legal and otherwise, makes it impossible not only to talk about the censored object, but about censorship.) There was clearly something much deeper than a political disagreement going on.

Sometimes I'm shocked at what shocks, the cultural relativism at work. The sculptures of Pompeii shocked the Europe of the 1700s, Kinsey shocked Americans in the 1940s, and Shakespeare shocks us now. Our oldest stories validate desire. I sometimes wish that those who rail about morality and normality would read a little anthropology and a bit of Homer. Myths and folklore are full of blunt, amused, and salacious stories, full of castration and masturbation and incest, necrophilia and zoophilia, the mysterious power of the vagina and the clitoris. Many cultures have practiced freer and more open sex l

Recenzii

"This book is not about pornography. No writer likes that question--'What's your book about?' It's almost impossible to sum up a book in a few words. In Talk Dirty to Me, I discuss pornography, prostitution, orgasms, fantasies, and other things sexual, but the book is about why these things are significant. The result is a 'philosophy'--an intimate, entirely personal philosophy about the role of sex in human life. I don't expect readers to agree or disagree with my ideas. (In fact, I hope I make most readers blush and complain at least once; that eternal elusiveness of explanation is part of what fascinates me about the subject.) My sexual philosophy is that of a bisexual woman of a certain generation and culture, and it can't encompass or explain much more than that. I consider myself 'sex-positive,' willing to celebrate the Iife-affirming nature of sex and to tolerate with cheer the enormous variations sex takes in human lives. Human beings will endlessly try to understand and explain sex to one another--and to themselves. That's what I've tried to do here."

--Sallie Tisdale

--Sallie Tisdale

Descriere

We live in a world in which most public images and interactions carry an element of sexual desire, yet it is nearly impossible for us to talk openly and honestly about sex. Talk Dirty to Me--a frank, funny, enlightened, and arousing portrait of sexuality in America--is the conversation we've been waiting for but have been afraid to start.

Notă biografică

Sallie Tisdale is a frequent contributor to Harper’s and her writing has also appeared in The New Yorker, Vogue, and Esquire, among others. She is an award-winning essayist and has received the Pushcart Prize. Among her seven books are Women of the Way and Stepping Westward.