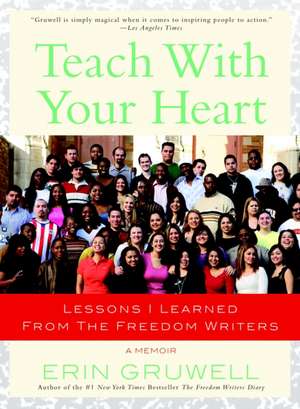

Teach with Your Heart: Lessons I Learned from the Freedom Writers

Autor Erin Gruwellen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2007

Preț: 116.57 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 175

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.31€ • 23.85$ • 18.60£

22.31€ • 23.85$ • 18.60£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767915847

ISBN-10: 0767915844

Pagini: 265

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767915844

Pagini: 265

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Recenzii

“Erin is a true inspiration and an example of the extraordinary difference one person can make in the world. She continues to transform the lives of students across the country through her work and The Freedom Writers Foundation.” — Hilary Swank, two-time Academy Award winner

“Ms. G., as the kids called her, embraced a concept that has been lost in modern life: writing can make pain tolerable, confusion clearer, and the self stronger.” — Anna Quindlen, winner of the Pulitzer Prize and author of the #1 New York Times bestseller Rise and Shine

“Ms. G., as the kids called her, embraced a concept that has been lost in modern life: writing can make pain tolerable, confusion clearer, and the self stronger.” — Anna Quindlen, winner of the Pulitzer Prize and author of the #1 New York Times bestseller Rise and Shine

Notă biografică

ERIN GRUWELL, the Freedom Writers, and her nonprofit organization, The Freedom Writers Foundation, have received many awards, including the prestigious Spirit of Anne Frank Award, and have appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show, Primetime, Good Morning America, and The View, to name a few. Erin Gruwell is also a charismatic motivational speaker who spreads her dynamic message to students, teachers, and business people around the world. She lives in southern California.

Extras

Chapter I

“Why do we have to read books by dead white guys in tights?” asked Sharaud, a foulmouthed sixteen–year–old, after he took one look at my syllabus.

Sharaud had entered my class at Woodrow Wilson High School in Long Beach, California, wearing a football jersey from Polytechnic High School. He must have known that donning the rival jersey was bound to get a rise out of the other students. He arrogantly strutted around my class, taunting the other players that he was going to take their places on the field, then leisurely strolled to the back of the classroom and took a seat.

As I started to discuss the curriculum, my students rocked in their seats and played percussion with their pencils. Some checked their pagers, while others reapplied their eyeliner. Some slouched, some laid their heads on the desks, and some actually took a nap. This was not the reception I was hoping for on my first day as a student teacher.

I dodged a paper airplane—made out of my syllabus, I quickly realized—and tried to make myself heard over a string of “yo mama” jokes.

I fidgeted with my pearls. I glanced at the polka-dot dress I was wearing—it was similar to the one that Julia Roberts wore in Pretty Woman—and wondered if I had chosen the wrong profession.

Why hadn’t I gone to law school like I’d originally planned? In a courtroom, unlike this chaotic classroom, a judge would bang his gavel with gusto after the first projectile had flown across the room, and any innuendo about his mother’s integrity would bring instant charges of contempt of court. I needed a daunting authority figure in a black robe to tell these kids that they were “out of order.” I looked around the room, but an authority figure was nowhere to be found. Then came a panicked realization—I was the authority figure, armed only with a broken piece of chalk.

As a student teacher, I should have been able to rely on my supervising teacher, but he had stepped out of the classroom. When I met with him over the summer, he suggested that it would be a good idea for me to begin teaching on the first day of school, rather than easing my way into it. “If you dive right in,” he said, “you’ll establish your authority from the get–go.” From the comfort of his living room, this suggestion sounded great. I had visions of passing out my syllabus and having students stick out their hands like Oliver Twist and ask for “more.” In reality, the only person requesting “more” was my supervising teacher, who conveniently snuck out to get “more” coffee and never returned.

After nearly forty years of teaching, my supervising teacher planned to retire at the end of the school year. He had emotionally checked out and was now simply coasting on autopilot. I’d assumed student teachers were to be handled like timid student drivers, with someone ready to grab the wheel when changing lanes or parallel parking went awry. Since my so–called mentor wasn’t there to put on the brakes or take control, I didn’t know which direction to go except forward.

To gain my composure, I tried to sound authoritative while reading my supervising teacher’s “Guidelines for Student Behavior.” I heard some students snickering. I stopped reading to see what they were laughing about.

“You got chalk on your ass,” yelled a student from the back.

“Daaamn, girl! Can I have some fries with that shake?” said another.

Somehow the “Guidelines” weren’t sticking, because the class was completely out of control. Even though I had studied classroom management, it was obvious that my students were the ones managing me. I just wanted to make it to the end of the hour.

Right before the bell rang, one of my students, Melvin, leaned back in his seat and announced, “I give her five days!”

“You’re on,” said Manny.

“I’m gonna make this lady cry in front of the whole class,” Sharaud bragged as he walked out the door.

At that moment, I could hear my father’s smug “I told you so” echo in my mind. A little less foreboding than “Beware the Ides of March,” but accurate nevertheless.

I felt like a failure. It was obvious that I didn’t know what I was doing. I had no idea how to engage these apathetic teenagers who hated reading, hated writing, and apparently hated me. And to make matters worse, student teachers did not receive salaries—we actually paid for the privilege! I was holding down two part–time jobs after school and on weekends to help pay for my semester’s tuition at the university. I worked at Nordstrom department store as a salesclerk in the lingerie department and at a Marriott Hotel as a concierge. Paying to teach in the trenches was like putting my face through a cutout hole at a carnival while a quarterback threw pies at me. At least with a carnival, I’d see it coming.

Once the students left, I picked up the paper airplane off the floor. I circled the room, collecting handouts that had been left behind, and saw ESL scribbled in black marker on several desks on the left side of the room. In educational jargon, ESL stands for English as a Second Language. Earlier, when I’d seen ESL etched on my door, I’d foolishly thought some Spanish-speaker was paying homage to my classroom. I soon realized this ESL had nothing to do with education—it was the acronym for East Side Longos—the largest Latino gang in Long Beach.

Similar gang insignias were on other desks. These defaced desks marked my students’ territory. The Asian students hit up the desks with the name of their respective gang affiliation, as did the African Americans. My multicultural classes in college had conveniently left out the chapter on gangs and turf warfare.

In lieu of a seating chart, I naively let the students pick their own seats. What struck me now was that they chose comfort zones determined by race. This realization gave me pause. I had imagined my students filing into my class and forming a melting pot of colors as they chose their seats, but the pot must have been pretty cold, because there was absolutely no melting. The Latinos had staked out the left side, while the Asian students occupied the right. The back row was occupied by all the African American students, and a couple of Caucasians sheepishly huddled together in the front.

My classroom wasn’t the only place where the students segregated themselves. It was worse out on the school quad. During lunch, the students again separated themselves based on racial identity. The students even had nicknamed their distinct areas: “Beverly Hills 90210,” “Chinatown” (even though most of the students were immigrants from Cambodia), the “Ghetto,” and “South of the Border.”

The transparent segregation of the school shocked me, especially since I was expecting Wilson to be a model of integration. On paper, it was one of the most culturally diverse schools in the country, and I’d chosen to studentteach at Wilson for exactly that reason. Clearly, there was a disparity between what I’d read about Wilson High and its reality.

My dad used to share stories about seeing segregation firsthand. In the early sixties, when he was drafted to play minor league baseball for the Washington Senators, some of his teammates were forced to drink out of separate fountains, eat at different sections in restaurants, and stay at separate motels whenever his team traveled through the South. As a catcher, my dad said “he judged a batter by his swing, not the color of his skin.” So when Hank Aaron started hitting balls out of the park, my father hailed him as his new hero and named his daughter Erin in honor of the legendary batter.

I was fascinated by my namesake for challenging the status quo and thus helping to change the face of America’s favorite pastime. I hoped Hammerin’ Hank’s influence would make its way out of the stadiums and into the classrooms. Disappointingly, it didn’t.

After lunch, all the kids from the “Beverly Hills 90210” section trotted to class together. Among them were students whose apparel and matching school sweatshirts identified them as water polo players, cheerleaders, and student council members. Their classrooms had banners that read “Home of the Distinguished Scholars,” along with freshly published textbooks and new computers. In contrast, my room was pretty barren. It didn’t have any banners, much less a computer. All I had to work with were hand–me–down textbooks riddled with graffiti.

In the Distinguished Scholars classrooms, the desks were neatly lined up and filled primarily with Caucasians. Nestled between the rows may have been an occasional African American or Asian student, but it was clear that a tracking system was in place.

The few Caucasians in my class were stigmatized as outcasts by their friends in the Distinguished Scholars program. The general assumption was that they had failed out of the Distinguished Scholars program, had a learning disability, or had just returned from rehab. By the look of things, some were probably on their way back in.

There was a perception in the affluent neighborhood south of the school that the caliber of students attending Wilson had plummeted in recent years. At one point, Wilson High was considered a highly desirable public high school, but there had been noticeable “white flight” after the school district implemented an intradistrict busing program. By the early nineties, the Caucasian population had decreased to less than twenty-five percent. Some speculated that the Distinguished Scholars program was an attempt to rescue the school’s declining reputation and keep neighborhood kids from transferring out. My hope was that I could find something “distinguished” in all of my students.

At the end of my first day, the security guard popped his head into my class. Earlier that morning, he had stopped me in the hallway. He had a walkie-talkie in one hand and a metal-detector wand in the other. “We have zero tolerance for weapons on campus,” he’d warned me. Then he asked to see my ID. I handed him my student ID card from the university. “I’m a student teacher,” I stammered. “I will be teaching junior English.”

“Sorry,” he said with a shrug, “you look like one of the students.”

Now the security guard was here to tell me, “There’s a police officer looking for you.”

“Why?” I asked. “Did somebody steal my car?”

“No,” he laughed, “he said he knows you.”

I went to the office and was surprised to see my old neighbor, Mark, in full police uniform.

“Mark, what are you doing here?” I asked.

“Your brother asked me to check up on you,” he said. Mark had been checking up on me since I was seven. He even threatened to beat up neighborhood boys with his nunchucks simply for flirting with me when we were in the sixth grade.

Mark and I had grown up in the same gated community, but I always suspected that he wanted to keep people out of those gates, whereas I wanted to bring them in. Our paths diverged after high school. I went on to college, and Mark entered the police academy. Coincidentally, we both ended up in Long Beach. It was obvious that Mark had not come to Long Beach out of moral obligation. He came to Long Beach because that’s where the action was.

“I don’t see any bullet holes, so I assume you survived your first day,” he said.

“Barely!” I laughed. “My family’s a little paranoid,” I offered. “My father called me this morning and said, ‘Erin, no matter what you do, please don’t eat the apples!’ He’s convinced they’re laced with strychnine or razor blades.”

“He’s probably right!” he said, and chuckled.

“Oh, come on. It’s not that bad!” I said.

“Don’t tell me it’s not that bad. I’m a cop, remember? I’m the one arresting these kids. There are parts of Long Beach that are like a war zone. Especially after the Rodney King riots. There have been about a hundred gang–related murders in Long Beach already this year.”

Growing up, my only exposure to “gangs” had been through the media or movies. My “hip” high school English teacher made us watch West Side Story to understand how the Montagues and the Capulets in Romeo and Juliet were like modern gangs. “Gangs” like the Jets and Sharks had staged rumbles. In real life, Jerome Robbins wasn’t choreographing Friday–night fights in Long Beach.

“I’d hate to see you get caught in the cross fire,” Mark said. “Just be careful.”

“I will,” I said, hugging him good-bye.

The security guard, who had been eavesdropping on my entire conversation, said, “He’s right, you know. Long Beach has changed a lot.”

At that moment, I just wanted to escape. I’d had enough negativity for one day, so I ducked into the teachers’ lounge to seek solace. The moment I walked in, conversation stopped. They looked me up and down and said nothing. They didn’t offer me a chair, a cup of coffee, or a word of encouragement. I looked down and noticed their open–toed Birkenstocks, in earthy contrast to my pumps. I must have looked like I had just stepped out of a Talbot’s catalog. I was definitely overdressed.

Their disapproving glances brought out insecurities that had never surfaced before. Obviously, I hadn’t made a good first impression. Maybe it was the polka dots. Or maybe it was my Tiffany pearls that pushed it over the top. Even though I craved their acceptance, it was pretty obvious that these particular teachers didn’t want me in their clique—or their lounge, for that matter. Maybe I was too young, too preppy, or maybe they assumed I’d been born with a silver spoon in my mouth. Their uncomfortable silence made it pretty obvious that they felt I didn’t belong.

I stood against the wall and listened to disgruntled banter about the new crop of students dubbed as “rejects.” Apparently, my class was not the only place where things had gone awry. The teachers, many of whom had taught at Wilson since the “good old days,” were discussing how the school was “going to hell in a handbasket.”

“This place has gone downhill ever since those kids started getting bussed in from the projects,” one teacher said.

“They don’t even care about school,” said another.

“They don’t care about anything!” said another.

Their casual banter about those kids was startling. I was troubled by how nonchalant they were with their pejorative comments. After a string of generalizations about those kids, the teachers moved on to something more specific.

“Did you hear about the latest disciplinary transfer from Poly?” one of the teachers asked.

I instantly suspected that they were talking about Sharaud, because he had sauntered into my class wearing his Poly jersey. “I heard he brought a gun to Poly last year and was planning to shoot everyone in the teachers’ lounge.”

“No, I heard he was planning to shoot his English teacher,” said another teacher.

“They only let him in here because they couldn’t find the gun. It’s just a matter of time before that boy blows someone away,” said another.

After being sufficiently ignored and hearing tales of how Sharaud would single-handedly destroy the institution. I decided I couldn't handle it anymore. I grabbed my bag and headed for the door. No one said good–bye. Why would they? They hadn’t even bothered to say hello.

I fumbled for my keys as I dashed to my car. The lingering conversation about Sharaud had struck fear into me. What if I was the next teacher who triggered him?

“Why do we have to read books by dead white guys in tights?” asked Sharaud, a foulmouthed sixteen–year–old, after he took one look at my syllabus.

Sharaud had entered my class at Woodrow Wilson High School in Long Beach, California, wearing a football jersey from Polytechnic High School. He must have known that donning the rival jersey was bound to get a rise out of the other students. He arrogantly strutted around my class, taunting the other players that he was going to take their places on the field, then leisurely strolled to the back of the classroom and took a seat.

As I started to discuss the curriculum, my students rocked in their seats and played percussion with their pencils. Some checked their pagers, while others reapplied their eyeliner. Some slouched, some laid their heads on the desks, and some actually took a nap. This was not the reception I was hoping for on my first day as a student teacher.

I dodged a paper airplane—made out of my syllabus, I quickly realized—and tried to make myself heard over a string of “yo mama” jokes.

I fidgeted with my pearls. I glanced at the polka-dot dress I was wearing—it was similar to the one that Julia Roberts wore in Pretty Woman—and wondered if I had chosen the wrong profession.

Why hadn’t I gone to law school like I’d originally planned? In a courtroom, unlike this chaotic classroom, a judge would bang his gavel with gusto after the first projectile had flown across the room, and any innuendo about his mother’s integrity would bring instant charges of contempt of court. I needed a daunting authority figure in a black robe to tell these kids that they were “out of order.” I looked around the room, but an authority figure was nowhere to be found. Then came a panicked realization—I was the authority figure, armed only with a broken piece of chalk.

As a student teacher, I should have been able to rely on my supervising teacher, but he had stepped out of the classroom. When I met with him over the summer, he suggested that it would be a good idea for me to begin teaching on the first day of school, rather than easing my way into it. “If you dive right in,” he said, “you’ll establish your authority from the get–go.” From the comfort of his living room, this suggestion sounded great. I had visions of passing out my syllabus and having students stick out their hands like Oliver Twist and ask for “more.” In reality, the only person requesting “more” was my supervising teacher, who conveniently snuck out to get “more” coffee and never returned.

After nearly forty years of teaching, my supervising teacher planned to retire at the end of the school year. He had emotionally checked out and was now simply coasting on autopilot. I’d assumed student teachers were to be handled like timid student drivers, with someone ready to grab the wheel when changing lanes or parallel parking went awry. Since my so–called mentor wasn’t there to put on the brakes or take control, I didn’t know which direction to go except forward.

To gain my composure, I tried to sound authoritative while reading my supervising teacher’s “Guidelines for Student Behavior.” I heard some students snickering. I stopped reading to see what they were laughing about.

“You got chalk on your ass,” yelled a student from the back.

“Daaamn, girl! Can I have some fries with that shake?” said another.

Somehow the “Guidelines” weren’t sticking, because the class was completely out of control. Even though I had studied classroom management, it was obvious that my students were the ones managing me. I just wanted to make it to the end of the hour.

Right before the bell rang, one of my students, Melvin, leaned back in his seat and announced, “I give her five days!”

“You’re on,” said Manny.

“I’m gonna make this lady cry in front of the whole class,” Sharaud bragged as he walked out the door.

At that moment, I could hear my father’s smug “I told you so” echo in my mind. A little less foreboding than “Beware the Ides of March,” but accurate nevertheless.

I felt like a failure. It was obvious that I didn’t know what I was doing. I had no idea how to engage these apathetic teenagers who hated reading, hated writing, and apparently hated me. And to make matters worse, student teachers did not receive salaries—we actually paid for the privilege! I was holding down two part–time jobs after school and on weekends to help pay for my semester’s tuition at the university. I worked at Nordstrom department store as a salesclerk in the lingerie department and at a Marriott Hotel as a concierge. Paying to teach in the trenches was like putting my face through a cutout hole at a carnival while a quarterback threw pies at me. At least with a carnival, I’d see it coming.

Once the students left, I picked up the paper airplane off the floor. I circled the room, collecting handouts that had been left behind, and saw ESL scribbled in black marker on several desks on the left side of the room. In educational jargon, ESL stands for English as a Second Language. Earlier, when I’d seen ESL etched on my door, I’d foolishly thought some Spanish-speaker was paying homage to my classroom. I soon realized this ESL had nothing to do with education—it was the acronym for East Side Longos—the largest Latino gang in Long Beach.

Similar gang insignias were on other desks. These defaced desks marked my students’ territory. The Asian students hit up the desks with the name of their respective gang affiliation, as did the African Americans. My multicultural classes in college had conveniently left out the chapter on gangs and turf warfare.

In lieu of a seating chart, I naively let the students pick their own seats. What struck me now was that they chose comfort zones determined by race. This realization gave me pause. I had imagined my students filing into my class and forming a melting pot of colors as they chose their seats, but the pot must have been pretty cold, because there was absolutely no melting. The Latinos had staked out the left side, while the Asian students occupied the right. The back row was occupied by all the African American students, and a couple of Caucasians sheepishly huddled together in the front.

My classroom wasn’t the only place where the students segregated themselves. It was worse out on the school quad. During lunch, the students again separated themselves based on racial identity. The students even had nicknamed their distinct areas: “Beverly Hills 90210,” “Chinatown” (even though most of the students were immigrants from Cambodia), the “Ghetto,” and “South of the Border.”

The transparent segregation of the school shocked me, especially since I was expecting Wilson to be a model of integration. On paper, it was one of the most culturally diverse schools in the country, and I’d chosen to studentteach at Wilson for exactly that reason. Clearly, there was a disparity between what I’d read about Wilson High and its reality.

My dad used to share stories about seeing segregation firsthand. In the early sixties, when he was drafted to play minor league baseball for the Washington Senators, some of his teammates were forced to drink out of separate fountains, eat at different sections in restaurants, and stay at separate motels whenever his team traveled through the South. As a catcher, my dad said “he judged a batter by his swing, not the color of his skin.” So when Hank Aaron started hitting balls out of the park, my father hailed him as his new hero and named his daughter Erin in honor of the legendary batter.

I was fascinated by my namesake for challenging the status quo and thus helping to change the face of America’s favorite pastime. I hoped Hammerin’ Hank’s influence would make its way out of the stadiums and into the classrooms. Disappointingly, it didn’t.

After lunch, all the kids from the “Beverly Hills 90210” section trotted to class together. Among them were students whose apparel and matching school sweatshirts identified them as water polo players, cheerleaders, and student council members. Their classrooms had banners that read “Home of the Distinguished Scholars,” along with freshly published textbooks and new computers. In contrast, my room was pretty barren. It didn’t have any banners, much less a computer. All I had to work with were hand–me–down textbooks riddled with graffiti.

In the Distinguished Scholars classrooms, the desks were neatly lined up and filled primarily with Caucasians. Nestled between the rows may have been an occasional African American or Asian student, but it was clear that a tracking system was in place.

The few Caucasians in my class were stigmatized as outcasts by their friends in the Distinguished Scholars program. The general assumption was that they had failed out of the Distinguished Scholars program, had a learning disability, or had just returned from rehab. By the look of things, some were probably on their way back in.

There was a perception in the affluent neighborhood south of the school that the caliber of students attending Wilson had plummeted in recent years. At one point, Wilson High was considered a highly desirable public high school, but there had been noticeable “white flight” after the school district implemented an intradistrict busing program. By the early nineties, the Caucasian population had decreased to less than twenty-five percent. Some speculated that the Distinguished Scholars program was an attempt to rescue the school’s declining reputation and keep neighborhood kids from transferring out. My hope was that I could find something “distinguished” in all of my students.

At the end of my first day, the security guard popped his head into my class. Earlier that morning, he had stopped me in the hallway. He had a walkie-talkie in one hand and a metal-detector wand in the other. “We have zero tolerance for weapons on campus,” he’d warned me. Then he asked to see my ID. I handed him my student ID card from the university. “I’m a student teacher,” I stammered. “I will be teaching junior English.”

“Sorry,” he said with a shrug, “you look like one of the students.”

Now the security guard was here to tell me, “There’s a police officer looking for you.”

“Why?” I asked. “Did somebody steal my car?”

“No,” he laughed, “he said he knows you.”

I went to the office and was surprised to see my old neighbor, Mark, in full police uniform.

“Mark, what are you doing here?” I asked.

“Your brother asked me to check up on you,” he said. Mark had been checking up on me since I was seven. He even threatened to beat up neighborhood boys with his nunchucks simply for flirting with me when we were in the sixth grade.

Mark and I had grown up in the same gated community, but I always suspected that he wanted to keep people out of those gates, whereas I wanted to bring them in. Our paths diverged after high school. I went on to college, and Mark entered the police academy. Coincidentally, we both ended up in Long Beach. It was obvious that Mark had not come to Long Beach out of moral obligation. He came to Long Beach because that’s where the action was.

“I don’t see any bullet holes, so I assume you survived your first day,” he said.

“Barely!” I laughed. “My family’s a little paranoid,” I offered. “My father called me this morning and said, ‘Erin, no matter what you do, please don’t eat the apples!’ He’s convinced they’re laced with strychnine or razor blades.”

“He’s probably right!” he said, and chuckled.

“Oh, come on. It’s not that bad!” I said.

“Don’t tell me it’s not that bad. I’m a cop, remember? I’m the one arresting these kids. There are parts of Long Beach that are like a war zone. Especially after the Rodney King riots. There have been about a hundred gang–related murders in Long Beach already this year.”

Growing up, my only exposure to “gangs” had been through the media or movies. My “hip” high school English teacher made us watch West Side Story to understand how the Montagues and the Capulets in Romeo and Juliet were like modern gangs. “Gangs” like the Jets and Sharks had staged rumbles. In real life, Jerome Robbins wasn’t choreographing Friday–night fights in Long Beach.

“I’d hate to see you get caught in the cross fire,” Mark said. “Just be careful.”

“I will,” I said, hugging him good-bye.

The security guard, who had been eavesdropping on my entire conversation, said, “He’s right, you know. Long Beach has changed a lot.”

At that moment, I just wanted to escape. I’d had enough negativity for one day, so I ducked into the teachers’ lounge to seek solace. The moment I walked in, conversation stopped. They looked me up and down and said nothing. They didn’t offer me a chair, a cup of coffee, or a word of encouragement. I looked down and noticed their open–toed Birkenstocks, in earthy contrast to my pumps. I must have looked like I had just stepped out of a Talbot’s catalog. I was definitely overdressed.

Their disapproving glances brought out insecurities that had never surfaced before. Obviously, I hadn’t made a good first impression. Maybe it was the polka dots. Or maybe it was my Tiffany pearls that pushed it over the top. Even though I craved their acceptance, it was pretty obvious that these particular teachers didn’t want me in their clique—or their lounge, for that matter. Maybe I was too young, too preppy, or maybe they assumed I’d been born with a silver spoon in my mouth. Their uncomfortable silence made it pretty obvious that they felt I didn’t belong.

I stood against the wall and listened to disgruntled banter about the new crop of students dubbed as “rejects.” Apparently, my class was not the only place where things had gone awry. The teachers, many of whom had taught at Wilson since the “good old days,” were discussing how the school was “going to hell in a handbasket.”

“This place has gone downhill ever since those kids started getting bussed in from the projects,” one teacher said.

“They don’t even care about school,” said another.

“They don’t care about anything!” said another.

Their casual banter about those kids was startling. I was troubled by how nonchalant they were with their pejorative comments. After a string of generalizations about those kids, the teachers moved on to something more specific.

“Did you hear about the latest disciplinary transfer from Poly?” one of the teachers asked.

I instantly suspected that they were talking about Sharaud, because he had sauntered into my class wearing his Poly jersey. “I heard he brought a gun to Poly last year and was planning to shoot everyone in the teachers’ lounge.”

“No, I heard he was planning to shoot his English teacher,” said another teacher.

“They only let him in here because they couldn’t find the gun. It’s just a matter of time before that boy blows someone away,” said another.

After being sufficiently ignored and hearing tales of how Sharaud would single-handedly destroy the institution. I decided I couldn't handle it anymore. I grabbed my bag and headed for the door. No one said good–bye. Why would they? They hadn’t even bothered to say hello.

I fumbled for my keys as I dashed to my car. The lingering conversation about Sharaud had struck fear into me. What if I was the next teacher who triggered him?

Descriere

A high school teacher in Long Beach, California, and participant in the Freedom Writers Project recounts how her students have helped her figure out the best ways to work for educational reform and continually renew her sense of commitment to and compassion for young people.