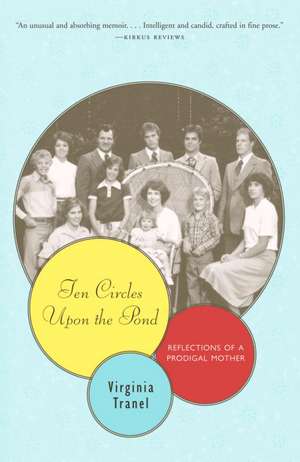

Ten Circles Upon the Pond

Autor Virginia Tranelen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2004

Tranel artfully weaves daily moments with world events as she reflects on how our culture affects our decisions. She offers candid observations on everything from her reproductive choices and feminism's influence on her thinking to sibling rivalries and her family's emotional response when an architect son emails firsthand reports of the horrors of September 11. Whether considering the issues intrinsic to marriage and child-raising, or questioning her own common sense, her insights are always provocative and deeply moving.

Preț: 77.32 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 116

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.80€ • 15.25$ • 12.49£

14.80€ • 15.25$ • 12.49£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400031214

ISBN-10: 1400031214

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 138 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 1400031214

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 138 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Virginia Tranel was born and raised in Dubuque, Iowa, and graduated from Clarke College with a degree in English and Spanish. In January 1957, she married Ned Tranel and moved west, settling finally in Billings, Montana. Her essays have appeared in magazines and anthologies, including the Notre Dame Press anthology of best essays, Family.

Extras

The Binding Problem

DANIEL

Traveling should be easy now. Our youngest child is three. No one is in diapers; everyone is capable of verbal communication, which complicates decision making but should preclude sudden eruptions on the upholstery. We're a happy, companionable family traveling from Ashland, Montana, to Houston, Texas, where my psychologist husband, Ned, will attend a conference on learning disabilities: eight children and two parents, sufficient numbers to justify our gas-guzzling Travelall in the midst of an oil embargo, plus enough clothes, equipment, and illusions to last twelve days. We're eager to get away from winter and Watergate's bad news and are looking forward to touring the Johnson Space Center, seeing the Gulf of Mexico, and, although no one has said it aloud, being unashamedly white for a while.

Two years have passed since we moved from Miles City, seventy miles north, to the house we built high on the hill above Ashland and the Tongue River. Our dining room windows frame the sunset over the Cheyenne reservation, the long-shadowed beauty of shale hills drenched in red and gold. Because we chose to live and work in this community, we enrolled our children in St. Labre Indian School rather than the public school where other white children go; we attend Sunday Mass at the mission church, a stone structure designed as a teepee buttressed with a Christian cross; at games, we sit on the Brave side of the bleachers and cheer against teams our children once played on; our kids invite school friends home for meals and weekends; this past Christmas season, Blake and Tony, two young Cheyenne brothers with no place to go, spent the holidays with us.

Still, the morning sun glares on our pale skin. Each day our children walk down the hill to school and learn more about the meaning of prejudice. One afternoon, our eight-year-old daughter, Monica, wide-eyed and breathless, was chased home by jeering Indian boys. Hey, white girl, watch out. We're gonna get you. During preseason football practice, our oldest son, Dan, lived with the team in a dorm. Rest remedied the brutal physical regimen of two practices a day but not the emotional strain of constant confrontation. He learned to be vigilant and tried to avoid fistfights with verbal tactics.

Reality is taking a toll on the romantic illusions that brought us here. Disturbing daily sights deepen the ache of isolation: a woman sprawled drunk at noon on the sidewalk in front of the bar; a young girl tucking a pinch of tobacco inside her lower lip; a man living in an abandoned car near a tangle of bushes by the river. A few days after we moved into our home, a group of giggling people emboldened by alcohol knocked on our front door to announce their hunger. Did we have food? I invited them in and opened the refrigerator to the woman. She searched the shelves, found cold boiled potatoes, and sliced them for sandwiches. A skinny, pockmarked man squatted on the floor next to Monica and joined her in a game of jacks. Another morning, a lone man drove out of his way to our house to ask if we had a little money for gas.

The issue isn't racial. What we're concerned about is exposing our children to a reality too grim for them to process. All children, not just ours, need time to make sense of their own lives before they can understand the predicaments of others. And teenagers need a circle of peers with whom they can entrust their dreams. Dan's sole confidant is Rick, a smart Cheyenne kid who plays the guitar and sings Jim Croce songs and is committed, as are many of the talented young, to spending his life here, helping his people.

This trip is supposed to be a vacation from coping. It's even supposed to be fun. But the car cruising so merrily down the road through the Crow Indian reservation is a cage on wheels, vibrating with punching, crying, bickering, all to the beat of hard rock. The driver of the vehicle is sixteen-year-old Dan, bright-eyed with a brand-new driver's license and bushy-headed with an Afro hairstyle. Intelligent, too, skilled and trustworthy. Furthermore, argued his father this morning, this highway driving will be good experience for him.

Risking a carful of people, though, is not a good experience for me. The blaring radio is rattling my confidence. I'm two weeks pregnant and still without symptoms (unless the dim-wittedness that lured me into this car is hormonal) and demoted to the "way back," the third seat where the youngest children ride, happily wrestling, playing reckless games of Slap Jack, looking out for things beginning with C that, when spotted, grant the observer the right to pinch someone. Hard. Preferably an unsuspecting napper. I glare at the untamed hair and the head bobbing to the rhythm of "Born to Be Wild." Is he noticing the gauges that tell facts about oil and brakes and gas? When he glances at the road, does he actually see it? Or has he escaped into the teenage never-never land of noise?

"Car!" someone shouts.

"Stop it!" I shout louder, meaning this car, this trip, and maybe even the direction of our lives. But certainly, the radio.

It takes three more shouts before my husband, the window passenger in the front seat, turns his head. "What?" Ned repeats my message to Dan, whose disgruntlement bristles in the rearview mirror.

"Huh? Down?" Dan's eyes round in disbelief. "Off? All the way off? Aw, Mom, c'mon. Be reasonable. It's Steppenwolf."

I gesture toward three-year-old Jennie, whose head is flopped at a forty-five-degree angle as she sleeps open-mouthed against Elizabeth's shoulder, then mime my words to facilitate lip reading. "Off. Or I drive."

Dan looks to his dad for an ally. Ned responds by reaching across Mike, in the center seat, and pressing the radio's off button.

"Jeez," Dan grumbles. "You guys spoil everything."

Mike, who'll be fifteen in a week and has planned our return trip to include a sentimental stop in Kansas, where he was born, unfolds a map at arm's length. "Over there is where Custer and the Indians fought." He frowns. "Actually, it wasn't really a fight. It was a massacre. Depending on how you look at it."

How you look at it depends, of course, on your ability to see. "Would you mind lowering the map, Mike?" I ask cheerfully. "It's blocking the windshield." My reputation as a wet blanket has been escalating ever since we pulled out of our driveway. Fifty miles ago. Which means one thousand six hundred and fifty miles to go. Why am I here? I wonder for the jillionth time. To know, love, and serve God and be happy with him in heaven comes the rote catechism reply, but it won't do. This is an existential challenge. Am I a self-determining agent responsible for the authenticity of my choices? Or an unconscious accessory to an ordained plan? My track record is incriminating. It began in Dubuque, Iowa, on a frigid January morning in 1957.

My wedding veil drifts over my face as, on my father's arm, I float down the aisle of St. Columbkille's Church in a gown of peau de soie, walking toward him, the dark-haired, restless man I don't know. At least, not in the biblical sense. I mask my eagerness by looking to the left of the altar where that other Virgin gazes back, a serene, blue-mantled statue inviting me with open arms into her mystery. My dad hands me over to Ned, an age-old property transaction, but I'm blissfully unaware. The nuptial Mass, celebrated by Ned's older brother, a priest, the binding vows to love through sickness and health until death do we part, the blessings and music blur by. And then I'm kneeling alone at Mary's feet to pray, a bridal custom I connect vaguely to virgins and vessels and acquiescence. But a prudent move, too, given Mary's role in Catholic tradition as mediatrix of all grace, a kind of funnel for God's blessings, a religious version of the maxim "The hand that rocks the cradle rules the world." As the mother of God, surely her hand has power. So does her left foot, deftly restraining a coiled snake, mythology's symbol of male fertility reincarnated as Christianity's tempter. Unaware of the serpent's former reputation, I stare into the blunt eyes and recall my seven-year-old self, veiled for my First Communion, kneeling in this same church before this same Virgin for whom I was named. I thank her for guiding me from veil to veil.

As we exit the church, friends bolster our fertility with a deluge of rice. The reception is a pleasant nuisance of well-wishers and cake and photographs. At last, I'm sitting beside Ned in the royal blue Chevy sedan he bought last week for $150. In the backseat are all of our possessions, packed for the two-thousand-mile trip to Pullman, Washington, where he'll begin work on a doctorate degree in psychology at the state university and I'll work in the accounting department at a job utterly unrelated to my interests or my college degree in English. My parents wave to us from the front porch. My mother dabs her eyes and says something to my dad, probably one of the proverbs she uses to explain idiosyncrasies and provide moral direction. "Birds of a feather flock together," she said to my brother when he brought home a friend whose character she questioned. "An idle mind is the devil's workshop," she told my sister when she found her daydreaming over her dusting assignment. "Familiarity breeds contempt," she warned when I went steady for the first time. Today, she might be saying, "They're young and haven't learned how life's corners must be turned."

"Still wet behind the ears," I imagine my dad responding as he puts an arm around her shoulder and swipes at his own eyes with the other hand. They shiver on the porch and eye the sign friends have tied to the bumper of our car. Trailing down the road behind us are three scrawled words: HOT SPRINGS TONIGHT!--code words for the longing of couples of that culture who'd lived out the lyrics "Love and marriage, love and marriage go together like a horse and carriage." Simply imagining the joy of consummation made brides blush and grooms sing a different tune: "Tonight, tonight, won't be just any night, tonight there will be no morning star."

Two right turns and we're on our way, naive newlyweds in a blue sedan streaking down the snowy highway like bold strokes on a white canvas. For all we know, those right turns were wrong, and, like artist Robert Motherwell, who claimed to begin each canvas with a series of mistakes, everything ahead of us would be a matter of correction.

"How far did you go the first night?" I once asked a newly married friend, meaning miles on the map. Her cheeks flamed. She stuttered, then smiled. "Well...we went, well, all the way...of course."

All the way across Iowa's hibernating cornfields we honeymoon. All the way across the blanketed wheat fields and sand hills of Nebraska. All the way across Wyoming's snow-swept rangeland, as white as my cast-off bridal gown. In Idaho, we climb into the pure, driven snow of White Bird Hill, where snowflakes swirl like a bridal veil, blinding us to the turns and twists in the road ahead. We put our faith in a mysterious blinking light tunneling north and follow a snowplow all the way to our destination--Pullman, Washington, a quaint town erupting from a sea of wheat. We open the door to an apartment rented over the telephone, three dingy rooms in an old house perched on a steep slope across Main Street from Washington State University.

We close the door behind us with a sigh. We've escaped the Korean War, the leaden winters and sticky summers of the Midwest, the obligation to plant roots in soil we consider unsuited to our fantasies. Ever since the college summers when Ned followed the wheat harvest through Nebraska and Montana, he's imagined his future on a sunny hilltop in the West. And now his dream and his name are mine.

While I yawn over tedious forms at my desk, Ned studies the behavioral patterns of rats and mice for insights into human conduct. My drowsiness is not entirely boredom. Somewhere in the Hot Springs of our honeymoon fantasy, probably in the real place of Rock Springs, Wyoming, our first child has been conceived.

One afternoon, as I'm walking home from that dreary desk, two dogs romping in an empty lot catch my eye. They sniff and growl and paw. They dance and skitter. The male rears up on his hind legs and thrusts toward her. She pauses, then sidesteps and drops him on all fours. Again and again, the anxious male tries to mount her; again and again, the jittery bitch leaps away. Finally, she surrenders to his pursuit, slides to a stop, and receives him. I walk faster, feeling found out, besmirched, unable to deny the essential similarity of the mating dance. But I know, too, the enormous difference between this animal frenzy and human lovemaking, an act that can, indeed, help create the ingredients of a loving relationship: trust, consideration, patience, and hope. I run the three blocks to our apartment, trying to outdistance the Victorian attitudes I meant to leave in Iowa's fenced fields. I'll need this animal instinct, along with Dr. Spock, to care for my first child.

"Hell, that's impossible," says my dad, when I call home to report our good news. His quick calculating has left him six days short of nine months and as astonished as the Virgin Mary before the angel Gabriel. Or perhaps what he finds impossible is imagining me, his strong-willed youngest child, as a mother. A vagabond mother, moreover, traveling cross-country again that summer according to her husband's career demands. A willing, eager vessel for a child destined to be a vagabond, too--conceived in Wyoming, quickening in Deadwood, South Dakota, waking me with middle-of-the-night heartburn in Savannah, Illinois, thumping my ribs at Craters of the Moon National Park in Idaho in September as we drive back to Washington State for another school year. A month before my October 20 due date, we settle into married student housing, a converted army barracks where our upstairs apartment has an extra bedroom and all of our neighbors have children.

Elizabeth shifts under Jennie's weight, scowls at the front seat, and jolts my consciousness with a question. "When do I get to drive? Or do the boys get to sit in the front seat for this entire trip?"

"You're only thirteen. And we've only been on the road for an hour. We'll switch places every two hours." I'm impressed at my impromptu diplomacy. The trouble is, no one in the front seat is paying any attention.

"Danny drove when he was thirteen."

"The tractor, maybe. Six miles an hour around the field."

"Oh, huh! Sure. Mom, you know better than that. He drove the pickup when he was eleven. And the car. Dad let him drive whenever he wanted. Just because he's a boy."

I exhale impatience. "He didn't drive on the highway with the whole family in the car."

DANIEL

Traveling should be easy now. Our youngest child is three. No one is in diapers; everyone is capable of verbal communication, which complicates decision making but should preclude sudden eruptions on the upholstery. We're a happy, companionable family traveling from Ashland, Montana, to Houston, Texas, where my psychologist husband, Ned, will attend a conference on learning disabilities: eight children and two parents, sufficient numbers to justify our gas-guzzling Travelall in the midst of an oil embargo, plus enough clothes, equipment, and illusions to last twelve days. We're eager to get away from winter and Watergate's bad news and are looking forward to touring the Johnson Space Center, seeing the Gulf of Mexico, and, although no one has said it aloud, being unashamedly white for a while.

Two years have passed since we moved from Miles City, seventy miles north, to the house we built high on the hill above Ashland and the Tongue River. Our dining room windows frame the sunset over the Cheyenne reservation, the long-shadowed beauty of shale hills drenched in red and gold. Because we chose to live and work in this community, we enrolled our children in St. Labre Indian School rather than the public school where other white children go; we attend Sunday Mass at the mission church, a stone structure designed as a teepee buttressed with a Christian cross; at games, we sit on the Brave side of the bleachers and cheer against teams our children once played on; our kids invite school friends home for meals and weekends; this past Christmas season, Blake and Tony, two young Cheyenne brothers with no place to go, spent the holidays with us.

Still, the morning sun glares on our pale skin. Each day our children walk down the hill to school and learn more about the meaning of prejudice. One afternoon, our eight-year-old daughter, Monica, wide-eyed and breathless, was chased home by jeering Indian boys. Hey, white girl, watch out. We're gonna get you. During preseason football practice, our oldest son, Dan, lived with the team in a dorm. Rest remedied the brutal physical regimen of two practices a day but not the emotional strain of constant confrontation. He learned to be vigilant and tried to avoid fistfights with verbal tactics.

Reality is taking a toll on the romantic illusions that brought us here. Disturbing daily sights deepen the ache of isolation: a woman sprawled drunk at noon on the sidewalk in front of the bar; a young girl tucking a pinch of tobacco inside her lower lip; a man living in an abandoned car near a tangle of bushes by the river. A few days after we moved into our home, a group of giggling people emboldened by alcohol knocked on our front door to announce their hunger. Did we have food? I invited them in and opened the refrigerator to the woman. She searched the shelves, found cold boiled potatoes, and sliced them for sandwiches. A skinny, pockmarked man squatted on the floor next to Monica and joined her in a game of jacks. Another morning, a lone man drove out of his way to our house to ask if we had a little money for gas.

The issue isn't racial. What we're concerned about is exposing our children to a reality too grim for them to process. All children, not just ours, need time to make sense of their own lives before they can understand the predicaments of others. And teenagers need a circle of peers with whom they can entrust their dreams. Dan's sole confidant is Rick, a smart Cheyenne kid who plays the guitar and sings Jim Croce songs and is committed, as are many of the talented young, to spending his life here, helping his people.

This trip is supposed to be a vacation from coping. It's even supposed to be fun. But the car cruising so merrily down the road through the Crow Indian reservation is a cage on wheels, vibrating with punching, crying, bickering, all to the beat of hard rock. The driver of the vehicle is sixteen-year-old Dan, bright-eyed with a brand-new driver's license and bushy-headed with an Afro hairstyle. Intelligent, too, skilled and trustworthy. Furthermore, argued his father this morning, this highway driving will be good experience for him.

Risking a carful of people, though, is not a good experience for me. The blaring radio is rattling my confidence. I'm two weeks pregnant and still without symptoms (unless the dim-wittedness that lured me into this car is hormonal) and demoted to the "way back," the third seat where the youngest children ride, happily wrestling, playing reckless games of Slap Jack, looking out for things beginning with C that, when spotted, grant the observer the right to pinch someone. Hard. Preferably an unsuspecting napper. I glare at the untamed hair and the head bobbing to the rhythm of "Born to Be Wild." Is he noticing the gauges that tell facts about oil and brakes and gas? When he glances at the road, does he actually see it? Or has he escaped into the teenage never-never land of noise?

"Car!" someone shouts.

"Stop it!" I shout louder, meaning this car, this trip, and maybe even the direction of our lives. But certainly, the radio.

It takes three more shouts before my husband, the window passenger in the front seat, turns his head. "What?" Ned repeats my message to Dan, whose disgruntlement bristles in the rearview mirror.

"Huh? Down?" Dan's eyes round in disbelief. "Off? All the way off? Aw, Mom, c'mon. Be reasonable. It's Steppenwolf."

I gesture toward three-year-old Jennie, whose head is flopped at a forty-five-degree angle as she sleeps open-mouthed against Elizabeth's shoulder, then mime my words to facilitate lip reading. "Off. Or I drive."

Dan looks to his dad for an ally. Ned responds by reaching across Mike, in the center seat, and pressing the radio's off button.

"Jeez," Dan grumbles. "You guys spoil everything."

Mike, who'll be fifteen in a week and has planned our return trip to include a sentimental stop in Kansas, where he was born, unfolds a map at arm's length. "Over there is where Custer and the Indians fought." He frowns. "Actually, it wasn't really a fight. It was a massacre. Depending on how you look at it."

How you look at it depends, of course, on your ability to see. "Would you mind lowering the map, Mike?" I ask cheerfully. "It's blocking the windshield." My reputation as a wet blanket has been escalating ever since we pulled out of our driveway. Fifty miles ago. Which means one thousand six hundred and fifty miles to go. Why am I here? I wonder for the jillionth time. To know, love, and serve God and be happy with him in heaven comes the rote catechism reply, but it won't do. This is an existential challenge. Am I a self-determining agent responsible for the authenticity of my choices? Or an unconscious accessory to an ordained plan? My track record is incriminating. It began in Dubuque, Iowa, on a frigid January morning in 1957.

My wedding veil drifts over my face as, on my father's arm, I float down the aisle of St. Columbkille's Church in a gown of peau de soie, walking toward him, the dark-haired, restless man I don't know. At least, not in the biblical sense. I mask my eagerness by looking to the left of the altar where that other Virgin gazes back, a serene, blue-mantled statue inviting me with open arms into her mystery. My dad hands me over to Ned, an age-old property transaction, but I'm blissfully unaware. The nuptial Mass, celebrated by Ned's older brother, a priest, the binding vows to love through sickness and health until death do we part, the blessings and music blur by. And then I'm kneeling alone at Mary's feet to pray, a bridal custom I connect vaguely to virgins and vessels and acquiescence. But a prudent move, too, given Mary's role in Catholic tradition as mediatrix of all grace, a kind of funnel for God's blessings, a religious version of the maxim "The hand that rocks the cradle rules the world." As the mother of God, surely her hand has power. So does her left foot, deftly restraining a coiled snake, mythology's symbol of male fertility reincarnated as Christianity's tempter. Unaware of the serpent's former reputation, I stare into the blunt eyes and recall my seven-year-old self, veiled for my First Communion, kneeling in this same church before this same Virgin for whom I was named. I thank her for guiding me from veil to veil.

As we exit the church, friends bolster our fertility with a deluge of rice. The reception is a pleasant nuisance of well-wishers and cake and photographs. At last, I'm sitting beside Ned in the royal blue Chevy sedan he bought last week for $150. In the backseat are all of our possessions, packed for the two-thousand-mile trip to Pullman, Washington, where he'll begin work on a doctorate degree in psychology at the state university and I'll work in the accounting department at a job utterly unrelated to my interests or my college degree in English. My parents wave to us from the front porch. My mother dabs her eyes and says something to my dad, probably one of the proverbs she uses to explain idiosyncrasies and provide moral direction. "Birds of a feather flock together," she said to my brother when he brought home a friend whose character she questioned. "An idle mind is the devil's workshop," she told my sister when she found her daydreaming over her dusting assignment. "Familiarity breeds contempt," she warned when I went steady for the first time. Today, she might be saying, "They're young and haven't learned how life's corners must be turned."

"Still wet behind the ears," I imagine my dad responding as he puts an arm around her shoulder and swipes at his own eyes with the other hand. They shiver on the porch and eye the sign friends have tied to the bumper of our car. Trailing down the road behind us are three scrawled words: HOT SPRINGS TONIGHT!--code words for the longing of couples of that culture who'd lived out the lyrics "Love and marriage, love and marriage go together like a horse and carriage." Simply imagining the joy of consummation made brides blush and grooms sing a different tune: "Tonight, tonight, won't be just any night, tonight there will be no morning star."

Two right turns and we're on our way, naive newlyweds in a blue sedan streaking down the snowy highway like bold strokes on a white canvas. For all we know, those right turns were wrong, and, like artist Robert Motherwell, who claimed to begin each canvas with a series of mistakes, everything ahead of us would be a matter of correction.

"How far did you go the first night?" I once asked a newly married friend, meaning miles on the map. Her cheeks flamed. She stuttered, then smiled. "Well...we went, well, all the way...of course."

All the way across Iowa's hibernating cornfields we honeymoon. All the way across the blanketed wheat fields and sand hills of Nebraska. All the way across Wyoming's snow-swept rangeland, as white as my cast-off bridal gown. In Idaho, we climb into the pure, driven snow of White Bird Hill, where snowflakes swirl like a bridal veil, blinding us to the turns and twists in the road ahead. We put our faith in a mysterious blinking light tunneling north and follow a snowplow all the way to our destination--Pullman, Washington, a quaint town erupting from a sea of wheat. We open the door to an apartment rented over the telephone, three dingy rooms in an old house perched on a steep slope across Main Street from Washington State University.

We close the door behind us with a sigh. We've escaped the Korean War, the leaden winters and sticky summers of the Midwest, the obligation to plant roots in soil we consider unsuited to our fantasies. Ever since the college summers when Ned followed the wheat harvest through Nebraska and Montana, he's imagined his future on a sunny hilltop in the West. And now his dream and his name are mine.

While I yawn over tedious forms at my desk, Ned studies the behavioral patterns of rats and mice for insights into human conduct. My drowsiness is not entirely boredom. Somewhere in the Hot Springs of our honeymoon fantasy, probably in the real place of Rock Springs, Wyoming, our first child has been conceived.

One afternoon, as I'm walking home from that dreary desk, two dogs romping in an empty lot catch my eye. They sniff and growl and paw. They dance and skitter. The male rears up on his hind legs and thrusts toward her. She pauses, then sidesteps and drops him on all fours. Again and again, the anxious male tries to mount her; again and again, the jittery bitch leaps away. Finally, she surrenders to his pursuit, slides to a stop, and receives him. I walk faster, feeling found out, besmirched, unable to deny the essential similarity of the mating dance. But I know, too, the enormous difference between this animal frenzy and human lovemaking, an act that can, indeed, help create the ingredients of a loving relationship: trust, consideration, patience, and hope. I run the three blocks to our apartment, trying to outdistance the Victorian attitudes I meant to leave in Iowa's fenced fields. I'll need this animal instinct, along with Dr. Spock, to care for my first child.

"Hell, that's impossible," says my dad, when I call home to report our good news. His quick calculating has left him six days short of nine months and as astonished as the Virgin Mary before the angel Gabriel. Or perhaps what he finds impossible is imagining me, his strong-willed youngest child, as a mother. A vagabond mother, moreover, traveling cross-country again that summer according to her husband's career demands. A willing, eager vessel for a child destined to be a vagabond, too--conceived in Wyoming, quickening in Deadwood, South Dakota, waking me with middle-of-the-night heartburn in Savannah, Illinois, thumping my ribs at Craters of the Moon National Park in Idaho in September as we drive back to Washington State for another school year. A month before my October 20 due date, we settle into married student housing, a converted army barracks where our upstairs apartment has an extra bedroom and all of our neighbors have children.

Elizabeth shifts under Jennie's weight, scowls at the front seat, and jolts my consciousness with a question. "When do I get to drive? Or do the boys get to sit in the front seat for this entire trip?"

"You're only thirteen. And we've only been on the road for an hour. We'll switch places every two hours." I'm impressed at my impromptu diplomacy. The trouble is, no one in the front seat is paying any attention.

"Danny drove when he was thirteen."

"The tractor, maybe. Six miles an hour around the field."

"Oh, huh! Sure. Mom, you know better than that. He drove the pickup when he was eleven. And the car. Dad let him drive whenever he wanted. Just because he's a boy."

I exhale impatience. "He didn't drive on the highway with the whole family in the car."

Recenzii

“An unusual and absorbing memoir. . . . Intelligent and candid, crafted in fine prose.” –Kirkus Reviews

“Could not be more timely. . . . Tranel's book will offer a good deal of solace to readers made anxious by current doom-and-gloom headlines. . . . [She] is upbeat, imparting parental wisdom in peppy aphorisms, but she also confides her doubts about her own parenting and her faith.”—Booklist

“Tranel’s simple and poetic prose...combined with her refreshingly open thoughts on life . . . make this portrait accessible to all readers. Highly recommended.” –Library Journal (starred)

“[Tranel] has managed to find a precious connection with all ten of her sons and daughters. That is the beauty of Ten Circles Upon The Pond. . . . [She] shows that she is at once so old-fashioned, yet so wise to the world she raised her brood in.”—Frank Deford, NPR commentator

“Could not be more timely. . . . Tranel's book will offer a good deal of solace to readers made anxious by current doom-and-gloom headlines. . . . [She] is upbeat, imparting parental wisdom in peppy aphorisms, but she also confides her doubts about her own parenting and her faith.”—Booklist

“Tranel’s simple and poetic prose...combined with her refreshingly open thoughts on life . . . make this portrait accessible to all readers. Highly recommended.” –Library Journal (starred)

“[Tranel] has managed to find a precious connection with all ten of her sons and daughters. That is the beauty of Ten Circles Upon The Pond. . . . [She] shows that she is at once so old-fashioned, yet so wise to the world she raised her brood in.”—Frank Deford, NPR commentator