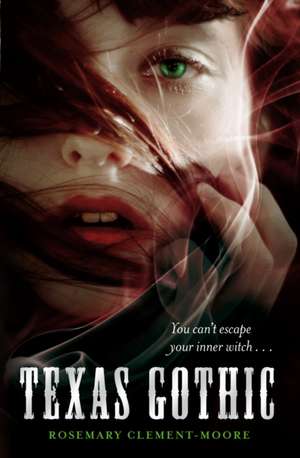

Texas Gothic

Autor Rosemary Clement-Mooreen Limba Engleză Paperback – 4 iul 2018

Preț: 78.89 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 118

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.10€ • 15.83$ • 12.59£

15.10€ • 15.83$ • 12.59£

Cartea se retipărește

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780552576680

ISBN-10: 0552576689

Pagini: 416

Dimensiuni: 129 x 198 x 35 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Editura: Random House

ISBN-10: 0552576689

Pagini: 416

Dimensiuni: 129 x 198 x 35 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Editura: Random House

Notă biografică

ROSEMARY CLEMENT-MOORE lives and writes in Arlington, Texas. Texas Gothic is her fifth book for young readers. You can visit Rosemary at ReadRosemary.com.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

The goat was in the tree again.

I hadn’t even known goats could climb trees. I had been livestock-sitting for three days before I’d figured out how the darned things kept getting out of their pen. Then one day I’d glanced out an upstairs window and seen Taco and Gordita, the ringleaders of the herd, trip-trip-tripping onto one of the low branches extending over the fence that separated their enclosure from the yard around Aunt Hyacinth’s century-old farmhouse.

“Don’t even think about it,” I told Gordita now, facing her across that same fence. I’d just bathed four dogs and then shoveled out the barn. I stank like dirty wet fur and donkey crap, and I was not in the mood to be trifled with.

She stared back at me with a placid, long-lashed eye and bleated, “Mba-a-a-a-a.” Which must translate as “You’re not the boss of me,” because she certainly didn’t trouble herself to get out of the tree.

“Suit yourself,” I said. As long as she was still technically in--or above--her pen, I didn’t have much of an argument. When dealing with nanny goats, you pick your battles.

I suppose Aunt Hyacinth could be forgiven for trusting me to figure out the finer points of goat management for myself. And “for myself” was no exaggeration. Except when my sister, Phin, and I had run into town to get groceries, we hadn’t seen a soul all week. Well, besides Uncle Burt. But you didn’t so much see Aunt Hyacinth’s late husband as sense his presence now and then.

This was Aunt Hyacinth’s first vacation in ten years. The herb farm and the line of organic bath products she produced here had finally reached a point where she could take time off. And she was going to be gone for a month, halfway around the world on a cruise through the Orient, so she’d had a lot of instructions to cover. Even after she’d given Phin and me an exhaustive briefing on the care and feeding of the flora and fauna, even while my mom had waited in the luggage-stuffed van to take her to the airport in San Antonio, Aunt Hy had stood on the porch, hands on her hips, lips pursed in concentration.

“I’m sure I’m forgetting something,” she’d said, scanning the yard for some reminder. Then she laughed and patted my cheek. “Oh, why am I worried? You’re a Goodnight. And if any of us can handle a crisis, Amy, it’s you.”

That was too true. I was the designated grown-up in a family that operated in a different reality than the rest of the world. But if the worst I had to deal with was a herd of goat Houdinis, I’d call myself lucky.

I gathered my dog-washing supplies and trudged toward the limestone ranch house that was the heart of Aunt Hyacinth’s Hill Country homestead. It was a respectable size for an herb farm, though small by ranching standards. Small enough, in fact, to be dwarfed by the surrounding land. To reach the place, you had to take a gravel road through someone else’s pasture to the Goodnight Farm gate, where a second fence of barbed wire and cedar posts surrounded Aunt Hyacinth’s acreage. We often saw our neighbors’ cows grazing through it. I guess the grass really was always greener. A packed dirt road led finally to the sturdy board fence that enclosed the house and yard with its adjoining livestock pens. Sometimes it felt like living inside a giant nesting doll. Ranching life was pretty much all about fences and gates.

The dogs had kept a respectful distance from the goats’ enclosure, but they bounded to join me on my way to the house. Sadie nipped at the heels of my rubber boots while Lila wove figure eights between my legs. Bear, no fool, had already headed for the shade to escape the afternoon sun.

“Get off!” I pushed the girls away from my filthy jeans. “I just washed you, you stupid mutts.”

They dashed to join Bear on the side porch. I clomped up the steps, my arms full of dirty towels, and hooked the screen door with a finger. The dogs tumbled into the mudroom after me, then tried to worm into the house while I toed off my boots.

“Not until you’re dry. Stay!” I managed to block them all except Pumpkin, a very appropriately named Pomeranian, who had asthma and got to come inside whenever he wanted. Which was pretty much all the time.

I closed the door and sighed--a mistake, because the deep breath told me just how much I stank.

Hot shower in T minus five, four, three . . .

The light over the sink in the kitchen went out. Not a crisis, since it was four in the afternoon. However, the soft hum of the air conditioner cut out at the same instant, which would be a problem very shortly. A big problem, because the only reason I’d agreed to spend my summer on Goodnight Farm--the last carefree summer of my life, before I started college and things that Really Count in Life--was that I knew it had civilized conveniences like climate control, wireless Internet, and satellite TV.

“Phin!” I shouted. I’d lived with my sister for seventeen years, not counting the last one, which she’d spent in the freshman dorm at the University of Texas. I knew exactly who was to blame for the power outage.

No answer, but that didn’t mean anything. Once Phin was immersed in one of her experiments, Godzilla could stroll over from the Gulf of Mexico and she wouldn’t notice unless his radioactive breath threw off her data.

Phin’s experiments were the reason I was currently covered in dog hair, straw dust, and donkey dung. She had eagerly agreed to house-sit because she wanted to do some kind of botanical research for her summer independent study, and, well . . . where better to do that than an herb farm? But while the Goodnight family might be eccentric by other people’s standards, no one was crazy enough to leave Phin solely in charge of Aunt Hyacinth’s livelihood. She couldn’t always be trusted to feed herself while she was working on a project, let alone the menagerie outside.

I peeled off my filthy socks and headed through the kitchen and living room to the back of the house, where Phin had commandeered Aunt Hyacinth’s workroom as her own. The door was closed, and I gave a cursory knock before I went in, only to stumble on the threshold between the bright afternoon and the startling darkness of the usually sunny space.

Without thinking, I flipped the light switch, but of course nothing happened. All I could see was a glow from Phin’s laptop and, strangely, from under the slate-topped table in the center of the room.

“Hey!” Phin’s voice was muffled, and a moment later her head popped up from behind the Rube Goldberg–type contraption on the table. Her strawberry-blond hair was coming loose from her ponytail, possibly because she was wearing what appeared to be a miner’s headlamp. “I’m doing an experiment.”

“I know.” I shaded my eyes from the light. “The fuse just blew.”

“Did it?” She checked some wires, punched something up on her laptop, then flipped a few switches on the power strip in front of her. “Oh. Good thing I’m at a stopping spot.”

“Well, thank heaven for that,” I said, but my tone was wasted on her. Irony was always wasted on Phin.

Aunt Hyacinth’s workroom was normally a bright, airy space, part sunroom, part apothecary. Just then, however, it was dark and stuffy, with heavy curtains covering the wall of windows and the glass door that led to the attached greenhouse.

On the huge worktable, Phin had set up her laptop and a bewildering rig that included a camera with some kind of complicated lens apparatus, a light box (which I suppose explained why the room was blacked out as if she were expecting the Luftwaffe), and enough electrical wiring to make me very nervous.

It wasn’t that Phin wasn’t brilliant. The only thing that might have kept her from getting a Nobel Prize someday was her field of study. Switzerland didn’t really recognize paranormal research. Neither did most of the world, but that never stopped a Goodnight. Except me, I suppose.

In the dim light, I could see something like electrode leads connected to the leaves of an unidentifiable potted plant. It said a lot about my sister that this was not the strangest thing I’d ever seen her do.

From the Hardcover edition.

I hadn’t even known goats could climb trees. I had been livestock-sitting for three days before I’d figured out how the darned things kept getting out of their pen. Then one day I’d glanced out an upstairs window and seen Taco and Gordita, the ringleaders of the herd, trip-trip-tripping onto one of the low branches extending over the fence that separated their enclosure from the yard around Aunt Hyacinth’s century-old farmhouse.

“Don’t even think about it,” I told Gordita now, facing her across that same fence. I’d just bathed four dogs and then shoveled out the barn. I stank like dirty wet fur and donkey crap, and I was not in the mood to be trifled with.

She stared back at me with a placid, long-lashed eye and bleated, “Mba-a-a-a-a.” Which must translate as “You’re not the boss of me,” because she certainly didn’t trouble herself to get out of the tree.

“Suit yourself,” I said. As long as she was still technically in--or above--her pen, I didn’t have much of an argument. When dealing with nanny goats, you pick your battles.

I suppose Aunt Hyacinth could be forgiven for trusting me to figure out the finer points of goat management for myself. And “for myself” was no exaggeration. Except when my sister, Phin, and I had run into town to get groceries, we hadn’t seen a soul all week. Well, besides Uncle Burt. But you didn’t so much see Aunt Hyacinth’s late husband as sense his presence now and then.

This was Aunt Hyacinth’s first vacation in ten years. The herb farm and the line of organic bath products she produced here had finally reached a point where she could take time off. And she was going to be gone for a month, halfway around the world on a cruise through the Orient, so she’d had a lot of instructions to cover. Even after she’d given Phin and me an exhaustive briefing on the care and feeding of the flora and fauna, even while my mom had waited in the luggage-stuffed van to take her to the airport in San Antonio, Aunt Hy had stood on the porch, hands on her hips, lips pursed in concentration.

“I’m sure I’m forgetting something,” she’d said, scanning the yard for some reminder. Then she laughed and patted my cheek. “Oh, why am I worried? You’re a Goodnight. And if any of us can handle a crisis, Amy, it’s you.”

That was too true. I was the designated grown-up in a family that operated in a different reality than the rest of the world. But if the worst I had to deal with was a herd of goat Houdinis, I’d call myself lucky.

I gathered my dog-washing supplies and trudged toward the limestone ranch house that was the heart of Aunt Hyacinth’s Hill Country homestead. It was a respectable size for an herb farm, though small by ranching standards. Small enough, in fact, to be dwarfed by the surrounding land. To reach the place, you had to take a gravel road through someone else’s pasture to the Goodnight Farm gate, where a second fence of barbed wire and cedar posts surrounded Aunt Hyacinth’s acreage. We often saw our neighbors’ cows grazing through it. I guess the grass really was always greener. A packed dirt road led finally to the sturdy board fence that enclosed the house and yard with its adjoining livestock pens. Sometimes it felt like living inside a giant nesting doll. Ranching life was pretty much all about fences and gates.

The dogs had kept a respectful distance from the goats’ enclosure, but they bounded to join me on my way to the house. Sadie nipped at the heels of my rubber boots while Lila wove figure eights between my legs. Bear, no fool, had already headed for the shade to escape the afternoon sun.

“Get off!” I pushed the girls away from my filthy jeans. “I just washed you, you stupid mutts.”

They dashed to join Bear on the side porch. I clomped up the steps, my arms full of dirty towels, and hooked the screen door with a finger. The dogs tumbled into the mudroom after me, then tried to worm into the house while I toed off my boots.

“Not until you’re dry. Stay!” I managed to block them all except Pumpkin, a very appropriately named Pomeranian, who had asthma and got to come inside whenever he wanted. Which was pretty much all the time.

I closed the door and sighed--a mistake, because the deep breath told me just how much I stank.

Hot shower in T minus five, four, three . . .

The light over the sink in the kitchen went out. Not a crisis, since it was four in the afternoon. However, the soft hum of the air conditioner cut out at the same instant, which would be a problem very shortly. A big problem, because the only reason I’d agreed to spend my summer on Goodnight Farm--the last carefree summer of my life, before I started college and things that Really Count in Life--was that I knew it had civilized conveniences like climate control, wireless Internet, and satellite TV.

“Phin!” I shouted. I’d lived with my sister for seventeen years, not counting the last one, which she’d spent in the freshman dorm at the University of Texas. I knew exactly who was to blame for the power outage.

No answer, but that didn’t mean anything. Once Phin was immersed in one of her experiments, Godzilla could stroll over from the Gulf of Mexico and she wouldn’t notice unless his radioactive breath threw off her data.

Phin’s experiments were the reason I was currently covered in dog hair, straw dust, and donkey dung. She had eagerly agreed to house-sit because she wanted to do some kind of botanical research for her summer independent study, and, well . . . where better to do that than an herb farm? But while the Goodnight family might be eccentric by other people’s standards, no one was crazy enough to leave Phin solely in charge of Aunt Hyacinth’s livelihood. She couldn’t always be trusted to feed herself while she was working on a project, let alone the menagerie outside.

I peeled off my filthy socks and headed through the kitchen and living room to the back of the house, where Phin had commandeered Aunt Hyacinth’s workroom as her own. The door was closed, and I gave a cursory knock before I went in, only to stumble on the threshold between the bright afternoon and the startling darkness of the usually sunny space.

Without thinking, I flipped the light switch, but of course nothing happened. All I could see was a glow from Phin’s laptop and, strangely, from under the slate-topped table in the center of the room.

“Hey!” Phin’s voice was muffled, and a moment later her head popped up from behind the Rube Goldberg–type contraption on the table. Her strawberry-blond hair was coming loose from her ponytail, possibly because she was wearing what appeared to be a miner’s headlamp. “I’m doing an experiment.”

“I know.” I shaded my eyes from the light. “The fuse just blew.”

“Did it?” She checked some wires, punched something up on her laptop, then flipped a few switches on the power strip in front of her. “Oh. Good thing I’m at a stopping spot.”

“Well, thank heaven for that,” I said, but my tone was wasted on her. Irony was always wasted on Phin.

Aunt Hyacinth’s workroom was normally a bright, airy space, part sunroom, part apothecary. Just then, however, it was dark and stuffy, with heavy curtains covering the wall of windows and the glass door that led to the attached greenhouse.

On the huge worktable, Phin had set up her laptop and a bewildering rig that included a camera with some kind of complicated lens apparatus, a light box (which I suppose explained why the room was blacked out as if she were expecting the Luftwaffe), and enough electrical wiring to make me very nervous.

It wasn’t that Phin wasn’t brilliant. The only thing that might have kept her from getting a Nobel Prize someday was her field of study. Switzerland didn’t really recognize paranormal research. Neither did most of the world, but that never stopped a Goodnight. Except me, I suppose.

In the dim light, I could see something like electrode leads connected to the leaves of an unidentifiable potted plant. It said a lot about my sister that this was not the strangest thing I’d ever seen her do.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

Starred Review, Kirkus Reviews, May 15, 2011:

"This engaging mystery has plenty of both paranormal and romance, spiced with loving families and satisfyingly packed with self-sufficient, competent girls."

Starred Review, School Library Journal, August 2011:

"It’s hard to picture a successful merging of Texas ranching culture with psychic ghost-hunting and witchcraft, but that’s what Clement-Moore has achieved in this novel laced with great characters, a healthy dose of humor, and a nod to popular culture...Teens looking for a rollicking adventure filled with paranormal events, dastardly evildoers, and laugh-out-loud moments as Amy and Ben argue and snipe their way to love will adore this book."

From the Hardcover edition.

"This engaging mystery has plenty of both paranormal and romance, spiced with loving families and satisfyingly packed with self-sufficient, competent girls."

Starred Review, School Library Journal, August 2011:

"It’s hard to picture a successful merging of Texas ranching culture with psychic ghost-hunting and witchcraft, but that’s what Clement-Moore has achieved in this novel laced with great characters, a healthy dose of humor, and a nod to popular culture...Teens looking for a rollicking adventure filled with paranormal events, dastardly evildoers, and laugh-out-loud moments as Amy and Ben argue and snipe their way to love will adore this book."

From the Hardcover edition.