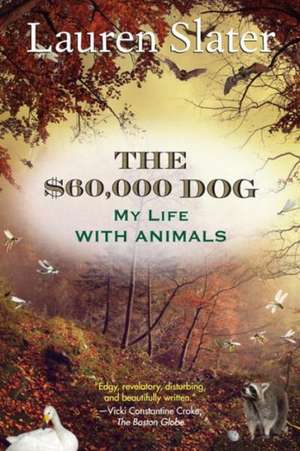

The $60,000 Dog: My Life with Animals

Autor Lauren Slateren Limba Engleză Paperback – 14 oct 2013

From the time she is nine years old, biking to the farmland outside her suburban home, where she discovers a disquieting world of sleeping cows and a “Private Way” full of the wondrous and creepy creatures of the wild—spiders, deer, moles, chipmunks, and foxes—Lauren Slater finds in animals a refuge from her troubled life. As she matures, her attraction to animals strengthens and grows more complex and compelling even as her family is falling to pieces around her. Slater spends a summer at horse camp, where she witnesses the alternating horrific and loving behavior of her instructor toward the animals in her charge and comes to question the bond that so often develops between females and their equines. Slater’s questions follow her to a foster family, her own parents no longer able to care for her. A pet raccoon, rescued from a hole in the wall, teaches her how to feel at home away from home. The two Shiba Inu puppies Slater adopts years later, against her husband’s will, grow increasingly important to her as she ages and her family begins to grow.

Slater’s husband is a born skeptic and possesses a sternly scientific view of animals as unconscious, primitive creatures, one who insists “that an animal’s worth is roughly equivalent to its edibility.” As one of her dogs, Lila, goes blind and the medical bills and monthly expenses begin to pour in, he calculates the financial burden of their canine family member and finds that Lila has cost them about $60,000, not to mention the approximately 400 pounds of feces she has deposited in their yard. But when Benjamin begins to suffer from chronic pain, Lauren is convinced it is Lila’s resilience and the dog’s quick adaptation to her blindness that draws her husband out of his own misery and motivates him to try to adjust to his situation. Ben never becomes a true believer or a die-hard animal lover, but his story and the stories Lauren tells of her own bond with animals convince her that our connections with the furry, the four-legged, the exoskeleton-ed, or the winged may be just as priceless as our human relationships.

The $60,000 Dog is Lauren Slater’s intimate manifesto on the unique, invaluable, and often essential contributions animals make to our lives. As a psychologist, a reporter, an amateur naturalist, and above all an enormously gifted writer, she draws us into the stories of her passion for animals that are so much more than pets. She describes her intense love for the animals in her life without apology and argues, finally, that the works of Darwin and other evolutionary biologists prove that, when it comes to worth, animals are equal, and in some senses even superior, to human beings.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 89.94 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 135

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.21€ • 18.02$ • 14.24£

17.21€ • 18.02$ • 14.24£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Livrare express 01-07 martie pentru 26.44 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780807001912

ISBN-10: 0807001910

Pagini: 251

Dimensiuni: 150 x 221 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: Beacon Press (MA)

ISBN-10: 0807001910

Pagini: 251

Dimensiuni: 150 x 221 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: Beacon Press (MA)

Recenzii

Praise for The $60,000 Dog

"Slater continually surprises wtih connections she makes. Beautifully written, and not just for animal lovers." —Kirkus Reviews

"A thoughtful examination of a sometimes difficult life, ameliorated and often alleviated by connections with nature and animals. . . .Dogs, wasps, and bats also figure in a poetic narrative that gives the reader a melodic look into a deeply considered life."—Booklist

“Assumption-busting, gut--wrenching, life-affirming.”—Pam Houston, MORE magazine

"Edgy, revelatory, disturbing, and beautifully written, Lauren Slater’s The $60,000 Dog is too unsentimental and idiosyncratic in structure to be lumped in with more traditional animal books."—Boston Globe

“A thoughtful memoir unravels the depth of our animal attachments.”—Elle

"It's the fearlessness along with the beauty that makes The $60,000 Dog a work of lasting achievement."—Minneapolis Star Tribune

Praise for Lauren Slater

“The beauty of Lauren Slater’s prose is shocking. . . . Slater’s vision is, ultimately, one of unity and possibility.”— Claire Messud, Newsday

“A lovely writer, easily read, often poetic.”— Michael Winerip, The New York Times Book Review

“An enormously poetic and ebullient writer.”— Elle

“Slater’s writing is confessional without being sentimental, honest without being overbearing.”— Joseph P. Kahn, The Boston Globe

“Slater is more poet than narrator, more philosopher than psychologist, more artist than doctor. . . . Every page brims with beautifully rendered images of thoughts, feelings, emotional states.”—The San Francisco Chronicle

From the Hardcover edition.

"Slater continually surprises wtih connections she makes. Beautifully written, and not just for animal lovers." —Kirkus Reviews

"A thoughtful examination of a sometimes difficult life, ameliorated and often alleviated by connections with nature and animals. . . .Dogs, wasps, and bats also figure in a poetic narrative that gives the reader a melodic look into a deeply considered life."—Booklist

“Assumption-busting, gut--wrenching, life-affirming.”—Pam Houston, MORE magazine

"Edgy, revelatory, disturbing, and beautifully written, Lauren Slater’s The $60,000 Dog is too unsentimental and idiosyncratic in structure to be lumped in with more traditional animal books."—Boston Globe

“A thoughtful memoir unravels the depth of our animal attachments.”—Elle

"It's the fearlessness along with the beauty that makes The $60,000 Dog a work of lasting achievement."—Minneapolis Star Tribune

Praise for Lauren Slater

“The beauty of Lauren Slater’s prose is shocking. . . . Slater’s vision is, ultimately, one of unity and possibility.”— Claire Messud, Newsday

“A lovely writer, easily read, often poetic.”— Michael Winerip, The New York Times Book Review

“An enormously poetic and ebullient writer.”— Elle

“Slater’s writing is confessional without being sentimental, honest without being overbearing.”— Joseph P. Kahn, The Boston Globe

“Slater is more poet than narrator, more philosopher than psychologist, more artist than doctor. . . . Every page brims with beautifully rendered images of thoughts, feelings, emotional states.”—The San Francisco Chronicle

From the Hardcover edition.

Cuprins

Chapter 1: The Egg

Chapter 2: Sugaring the Bit

Chapter 3: Old Homes

Chapter 4: The Swan with a Broken Beak

Chapter 5: The Sixty Thousand-Dollar Dog

Chapter 6: The Death of a Wasp

Chapter 7: Bat Dreams

Acknowledgments

Chapter 2: Sugaring the Bit

Chapter 3: Old Homes

Chapter 4: The Swan with a Broken Beak

Chapter 5: The Sixty Thousand-Dollar Dog

Chapter 6: The Death of a Wasp

Chapter 7: Bat Dreams

Acknowledgments

Notă biografică

Lauren Slater is the author of six books, including Welcome to My Country, Lying: A Metaphorical Memoir, Opening Skinner’s Box, the short-story collection Blue Beyond Blue, and Love Works Like This, which chronicled the agonizing decisions she made relating to her psychiatric illness and her pregnancy. Slater has been the recipient of numerous awards, including a 2004 National Endowments for the Arts Award, multiple inclusions in Best American volumes, and a Knight Science Journalism fellowship at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Slater was a practicing psychologist for eleven years before embarking on a full-time writing career. She served as the clinical and later executive director of AfterCare Services. Slater lives and writes in Harvard, Massachusetts.

Extras

From Chapter 5

Pressure

My dog, Lila, is forty pounds packed with muscle and grit. Her hide is as rough as the rind of a cantaloupe, covered with course hair that is nevertheless somehow soft to the touch. She is a dumb dog in the sense that all dogs are dumb, driven by genes and status, she will willingly fight any mammal that threatens her alpha position, and she delights in bones, big greasy bones she can crunch in her curved canines, and then swallow, splinters and all.

My husband disparages Lila, and, to his credit, there is much there to disparage. She lacks the capacity for critical thought. She has deposited in our yard an estimated four hundred pounds of feces during her ten-year tenure with us. Her urine has bleached our green grass so the lawn is now a bright yellow-lime, the same shade as the world seen through a pair of poorly tinted sunglasses, at once glaring and false. Lila farts and howls. Lila sheds and drools. Lila costs us more per year to maintain than does the oil to heat our home. There is her food; her vaccinations; her grooming; the four times yearly palpating of her anal glands; her heartworm medications; her chew toys; her city leash; her second, country retractable leash; her dog bed; the emergency veterinary visits when she gets ill; the sheer time it takes to walk her (my husband estimates my rate at fifty dollars per hour). Picture him, my husband, at night, the children tucked in bed, punching the keys on his calculator. Picture Lila, unsuspecting (and this is why she charms us, is it not?), draped across his feet, dreaming of deer and rivers as he figures the cost of her existence meshed with ours. It is cold outside. The air cracks like a pane of glass and sends its shards straight up our noses. He presses = and announces the price he claims is right. Sixty thousand. The cost of Lila’s life. I look out the window. The lawn she’s bleached is covered with a fine film of snow and the sky above is as dark as a blackboard, scrawled with stars and beyond them—what? Six trillion suns. Ancient radiation that still sizzles in our air. Scientists now claim there is more than one universe, but precisely how many more? No one knows. Some things cannot be calculated. I won’t tell my husband this. I love my husband. I love Lila too.

Why I love Lila is not clear. The facts, after all, are the facts. There are, by some estimates, 2 million tons of dog feces deposited annually on American sidewalks and in American parks and lawns. The volume of the collective canine liquid output in this country has been estimated at 4 billion gallons. Dogs are the carriers of more than sixty-five diseases they can pass to their human counterparts. Some of the more well-known ones are rabies, tuberculosis, and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Six hundred and fifty four people died last year in the United States from dog bites, and over thirty thousand were injured enough to require a visit to the emergency room. Seems a no brainer, right? Knowing these facts, you would have to be as dumb as a dog to have a dog in your home.

Now, another small fact. I don’t have one dog. I have two. And if I had a bigger home, I would have three. Maybe even four. Or more. My idea of heaven on earth is to have as many dogs as I do socks, or spoons. All the facts in the world cannot change the final fact in this matter, which is that dogs and I—we get along.

I don’t know why this is. Nor do I know why I so adore dogs while my husband fairly despises them. I have a hunch, though not up to investigation. Still, here it is. Dogs evolved from wolves. The modern-day human evolved from the Cro-Magnon man. A long time ago, so long that even all the dog scat stretched into a single smelly string could not go that far, a few wolf pups crept into a few Cro-Magnon caves and kept some scared families company in a night dense with danger. These wolf pups howled warning when a wildebeest was near. Their multilayered coats emitted continuous waves of warmth. Faster than us on their feet, they became indispensable hunting aides, twisting up in the air and bringing down the deer, teeth sunk into the blood-speckled neck of an animal we feasted on, sharing scraps, breaking bread with these canids whose evolution is all tied up with ours. Eventually, these progenitor pups, perpetually in our presence, grew domesticated, and thus the dawning of the dog. This, understand, is the short, short, short version of what was probably in reality a synergistic push and pull, a unique kind of coevolution that kept on keeping on over spans of thousands and thousands of years.

Sometimes, if I lie very still in the flat part of our field and if, as I do so, I stare up at the spattered sky, I think I can feel those years tumbling me over and down, over and down and back. My guess? I must have descended from those early wolf-welcoming Cro-Magnons, those hairy hunters with the genetic predisposition that allowed them to open doors they didn’t know they had. I must have descended from a line of people, who liked the stink of the wild, smelling it on their palms pressed up to their faces; who knew long before Crick unraveled the chromosome that there was not much difference between our genome and theirs. And these people, per- haps they were lonely and needed the feel of fur in order to salve the skin-stinging openness of the Pliocene plains. Most of all I believe we believed, even back then—a wordless, wild belief—that humans only become beings in relation to the animals with whom we share this planet; the differences defines us and the similarities remind us of some essential primitive cry we keep a clamp on.

The bottom line? Maybe Homo can only be Sapien (wise) when he respects the radical others who populate our blue ball, when he considers their sentient suffering and their planes of knowledge. Literary critic Donna Haraway puts it well when she writes in her book The Companion Species Manifesto, “Dogs, in their historical complexity, matter here. Dogs are not an alibi for other themes; dogs are fleshy material-semiotic presences in the body of techno- science. Dogs are not surrogates for theory; they are not here just to think with. They are here to live with. Partners in the crime of human evolution, they are in the garden from the get-go.” This is all a lot of hog wash, or poodle poop, according to my husband. Jacques Derrida wrote about feeling shame when he saw the face of an animal in part because that face reflected back to him his moral failings as a man amongst men who had trampled the planet past the point of recognition, almost. My husband is a gentle man who cares about this planet. He says sorry to a tree before he cuts it down. He dutifully recycles, patiently sorting our scumbled trash, putting tin in the blue bin, plastics in the pink. He grows exotic mushrooms in our backyard’s shadiest spot, fragrant plants with gilled undersides and suede-soft caps of gray. But when it comes to dogs, my husband feels next to nothing. He has, I think, a kind of canid autism, almost utterly unable to engage in the social play between people and their pooches. His actions and attitude lead me to wonder if his long line is entirely different from mine. While I must be descended from those hairy hunters with genetic pre- dispositions that encouraged them to welcome wolf, my husband, well, he must come from a tribe the genetic constitution of which lead them to either overtly reject the canine or simply fail to hear his knock at their door. Some theorists believe that the reason why the Neanderthals became extinct is because they never took to the pups sniffing the perimeters of their property and thus lost out on all the riches that the human/canine relationship had to offer. As the Cro-Magnon flourished, the Neanderthals—living in an iced-over Europe, in a land of perpetual twilit snow—dwindled down; cold, hunger, scarcity the name of their game. What this may mean: all those “not dog” people, the ones who push away the paws and straighten their skirts after being sniffed, well, they may have one foot in the chromosomally compromised Neanderthal pool, while, on the other hand, those of us who sneak food to Fido, roam with Rover, or insist that the Pekinese is put on the bed each night, well, we may be displaying not idiocy or short-sighted sentimentality, as our critics would call it, but a sign of our superior genetic lineage. It’s possible. But I don’t want to tell my husband this. I’d hate to hurt his feelings.

Despite our different attitudes towards dogs in particular, pets in general (we also have a cat, two hamsters, and I’m planning on hens and horses when we move full time to the country) have not been a subject of sore dispute in our home until recently. In the past, my husband and I have had brief spats about Lila and her brother, Musashi, but nothing that led to a deep and abiding impasse. Now, however, circumstances are starting to change. When I got the dogs they were puppies, and so were we. Twelve years later, I have begun to read the obituaries in the paper. I worry about osteoporosis, and I experience occasional sciatica. My eye- sight is going, the distance still crisp but all that comes close to me fuzzy. Furred. Words warp and melt, slipping sideways on the page. The other day, while admiring my hydrangea in the garden, I could not recall its name. Hydrangea. Hydrangea. Hydrangea. Now I walk around repeating the names of plants to myself, as if words will keep my world intact. Hydrangea. Aster. Sedum. Astilbe.

My husband, a deeply private person, has his own assortment of worries, aches, and pains. Two years or so ago his arms started to hurt, a flaming deep in the muscles. The pain had made him smaller, solitary, sitting in his study, his wrists gleaming with Bengay. Before he left his job, unable to use a keyboard, he worked sixty, seventy hours a week and got his exercise while commuting in his car, steering with his left hand and lifting a five-pound weight with his right. Then he’d switch sides. He claimed that kept him in cardiovascular shape. I view this claim as the distortions of a desperate man. Forty-five, forty-six, forty-seven. Unemployed, now; cornered and chronic. He has a beautiful bald spot on his head, a perfect cream-colored circle haloed by red hair. He knows enough not to try a comb-over. Our children see his bald spot as a toy. Our son races his cars around and around its circumference. Our daughter draws on it: Two eyes. A heart. Enough, he says. Enough. As for our dogs, our aging reflects theirs or theirs ours. Musashi, the elder of our canines, appears blessed with youthful genes, his only sign a whitening of the whiskers. But Lila, like me, is going gray all over, her urine mysteriously tinged with pus and blood, her hips eroding, clumps of fur falling from her hide, her skin beneath raw red and scaly.

Pressure

My dog, Lila, is forty pounds packed with muscle and grit. Her hide is as rough as the rind of a cantaloupe, covered with course hair that is nevertheless somehow soft to the touch. She is a dumb dog in the sense that all dogs are dumb, driven by genes and status, she will willingly fight any mammal that threatens her alpha position, and she delights in bones, big greasy bones she can crunch in her curved canines, and then swallow, splinters and all.

My husband disparages Lila, and, to his credit, there is much there to disparage. She lacks the capacity for critical thought. She has deposited in our yard an estimated four hundred pounds of feces during her ten-year tenure with us. Her urine has bleached our green grass so the lawn is now a bright yellow-lime, the same shade as the world seen through a pair of poorly tinted sunglasses, at once glaring and false. Lila farts and howls. Lila sheds and drools. Lila costs us more per year to maintain than does the oil to heat our home. There is her food; her vaccinations; her grooming; the four times yearly palpating of her anal glands; her heartworm medications; her chew toys; her city leash; her second, country retractable leash; her dog bed; the emergency veterinary visits when she gets ill; the sheer time it takes to walk her (my husband estimates my rate at fifty dollars per hour). Picture him, my husband, at night, the children tucked in bed, punching the keys on his calculator. Picture Lila, unsuspecting (and this is why she charms us, is it not?), draped across his feet, dreaming of deer and rivers as he figures the cost of her existence meshed with ours. It is cold outside. The air cracks like a pane of glass and sends its shards straight up our noses. He presses = and announces the price he claims is right. Sixty thousand. The cost of Lila’s life. I look out the window. The lawn she’s bleached is covered with a fine film of snow and the sky above is as dark as a blackboard, scrawled with stars and beyond them—what? Six trillion suns. Ancient radiation that still sizzles in our air. Scientists now claim there is more than one universe, but precisely how many more? No one knows. Some things cannot be calculated. I won’t tell my husband this. I love my husband. I love Lila too.

Why I love Lila is not clear. The facts, after all, are the facts. There are, by some estimates, 2 million tons of dog feces deposited annually on American sidewalks and in American parks and lawns. The volume of the collective canine liquid output in this country has been estimated at 4 billion gallons. Dogs are the carriers of more than sixty-five diseases they can pass to their human counterparts. Some of the more well-known ones are rabies, tuberculosis, and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Six hundred and fifty four people died last year in the United States from dog bites, and over thirty thousand were injured enough to require a visit to the emergency room. Seems a no brainer, right? Knowing these facts, you would have to be as dumb as a dog to have a dog in your home.

Now, another small fact. I don’t have one dog. I have two. And if I had a bigger home, I would have three. Maybe even four. Or more. My idea of heaven on earth is to have as many dogs as I do socks, or spoons. All the facts in the world cannot change the final fact in this matter, which is that dogs and I—we get along.

I don’t know why this is. Nor do I know why I so adore dogs while my husband fairly despises them. I have a hunch, though not up to investigation. Still, here it is. Dogs evolved from wolves. The modern-day human evolved from the Cro-Magnon man. A long time ago, so long that even all the dog scat stretched into a single smelly string could not go that far, a few wolf pups crept into a few Cro-Magnon caves and kept some scared families company in a night dense with danger. These wolf pups howled warning when a wildebeest was near. Their multilayered coats emitted continuous waves of warmth. Faster than us on their feet, they became indispensable hunting aides, twisting up in the air and bringing down the deer, teeth sunk into the blood-speckled neck of an animal we feasted on, sharing scraps, breaking bread with these canids whose evolution is all tied up with ours. Eventually, these progenitor pups, perpetually in our presence, grew domesticated, and thus the dawning of the dog. This, understand, is the short, short, short version of what was probably in reality a synergistic push and pull, a unique kind of coevolution that kept on keeping on over spans of thousands and thousands of years.

Sometimes, if I lie very still in the flat part of our field and if, as I do so, I stare up at the spattered sky, I think I can feel those years tumbling me over and down, over and down and back. My guess? I must have descended from those early wolf-welcoming Cro-Magnons, those hairy hunters with the genetic predisposition that allowed them to open doors they didn’t know they had. I must have descended from a line of people, who liked the stink of the wild, smelling it on their palms pressed up to their faces; who knew long before Crick unraveled the chromosome that there was not much difference between our genome and theirs. And these people, per- haps they were lonely and needed the feel of fur in order to salve the skin-stinging openness of the Pliocene plains. Most of all I believe we believed, even back then—a wordless, wild belief—that humans only become beings in relation to the animals with whom we share this planet; the differences defines us and the similarities remind us of some essential primitive cry we keep a clamp on.

The bottom line? Maybe Homo can only be Sapien (wise) when he respects the radical others who populate our blue ball, when he considers their sentient suffering and their planes of knowledge. Literary critic Donna Haraway puts it well when she writes in her book The Companion Species Manifesto, “Dogs, in their historical complexity, matter here. Dogs are not an alibi for other themes; dogs are fleshy material-semiotic presences in the body of techno- science. Dogs are not surrogates for theory; they are not here just to think with. They are here to live with. Partners in the crime of human evolution, they are in the garden from the get-go.” This is all a lot of hog wash, or poodle poop, according to my husband. Jacques Derrida wrote about feeling shame when he saw the face of an animal in part because that face reflected back to him his moral failings as a man amongst men who had trampled the planet past the point of recognition, almost. My husband is a gentle man who cares about this planet. He says sorry to a tree before he cuts it down. He dutifully recycles, patiently sorting our scumbled trash, putting tin in the blue bin, plastics in the pink. He grows exotic mushrooms in our backyard’s shadiest spot, fragrant plants with gilled undersides and suede-soft caps of gray. But when it comes to dogs, my husband feels next to nothing. He has, I think, a kind of canid autism, almost utterly unable to engage in the social play between people and their pooches. His actions and attitude lead me to wonder if his long line is entirely different from mine. While I must be descended from those hairy hunters with genetic pre- dispositions that encouraged them to welcome wolf, my husband, well, he must come from a tribe the genetic constitution of which lead them to either overtly reject the canine or simply fail to hear his knock at their door. Some theorists believe that the reason why the Neanderthals became extinct is because they never took to the pups sniffing the perimeters of their property and thus lost out on all the riches that the human/canine relationship had to offer. As the Cro-Magnon flourished, the Neanderthals—living in an iced-over Europe, in a land of perpetual twilit snow—dwindled down; cold, hunger, scarcity the name of their game. What this may mean: all those “not dog” people, the ones who push away the paws and straighten their skirts after being sniffed, well, they may have one foot in the chromosomally compromised Neanderthal pool, while, on the other hand, those of us who sneak food to Fido, roam with Rover, or insist that the Pekinese is put on the bed each night, well, we may be displaying not idiocy or short-sighted sentimentality, as our critics would call it, but a sign of our superior genetic lineage. It’s possible. But I don’t want to tell my husband this. I’d hate to hurt his feelings.

Despite our different attitudes towards dogs in particular, pets in general (we also have a cat, two hamsters, and I’m planning on hens and horses when we move full time to the country) have not been a subject of sore dispute in our home until recently. In the past, my husband and I have had brief spats about Lila and her brother, Musashi, but nothing that led to a deep and abiding impasse. Now, however, circumstances are starting to change. When I got the dogs they were puppies, and so were we. Twelve years later, I have begun to read the obituaries in the paper. I worry about osteoporosis, and I experience occasional sciatica. My eye- sight is going, the distance still crisp but all that comes close to me fuzzy. Furred. Words warp and melt, slipping sideways on the page. The other day, while admiring my hydrangea in the garden, I could not recall its name. Hydrangea. Hydrangea. Hydrangea. Now I walk around repeating the names of plants to myself, as if words will keep my world intact. Hydrangea. Aster. Sedum. Astilbe.

My husband, a deeply private person, has his own assortment of worries, aches, and pains. Two years or so ago his arms started to hurt, a flaming deep in the muscles. The pain had made him smaller, solitary, sitting in his study, his wrists gleaming with Bengay. Before he left his job, unable to use a keyboard, he worked sixty, seventy hours a week and got his exercise while commuting in his car, steering with his left hand and lifting a five-pound weight with his right. Then he’d switch sides. He claimed that kept him in cardiovascular shape. I view this claim as the distortions of a desperate man. Forty-five, forty-six, forty-seven. Unemployed, now; cornered and chronic. He has a beautiful bald spot on his head, a perfect cream-colored circle haloed by red hair. He knows enough not to try a comb-over. Our children see his bald spot as a toy. Our son races his cars around and around its circumference. Our daughter draws on it: Two eyes. A heart. Enough, he says. Enough. As for our dogs, our aging reflects theirs or theirs ours. Musashi, the elder of our canines, appears blessed with youthful genes, his only sign a whitening of the whiskers. But Lila, like me, is going gray all over, her urine mysteriously tinged with pus and blood, her hips eroding, clumps of fur falling from her hide, her skin beneath raw red and scaly.