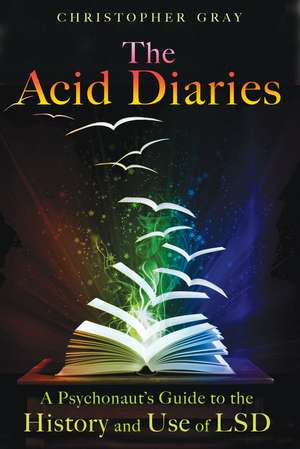

The Acid Diaries: A Psychonaut's Guide to the History and Use of LSD

Autor Christopher Grayen Limba Engleză Paperback – 24 sep 2010

Preț: 76.62 lei

Preț vechi: 102.18 lei

-25% Nou

Puncte Express: 115

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.67€ • 15.94$ • 12.33£

14.67€ • 15.94$ • 12.33£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-16 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781594773839

ISBN-10: 1594773831

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Park Street Press

ISBN-10: 1594773831

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Park Street Press

Notă biografică

Christopher Gray (1942-2009) was well known for his involvement in the 1960s with Situationist International, for his various radical writings, and as Swami Prem Paritosh, disciple of the guru Osho. He translated Raoul Vaneigem’s Banalités de Base (as The Totality for Kids) and is the author of Leaving the Twentieth Century, the first English- language anthology of Situationist ideas, and the biography Life of Osho.

Extras

Chapter 3

The Doors of Perception

What no one dreamed was that the drug was about to become part of the roller coaster political ride of the 1960s. The first step toward this happening was that the drug began to break free of doctors and psychoanalysts. For during the early 1960s, LSD was still perfectly legal and, providing you had halfway reasonable professional qualifications, independent research projects could be set up with relative ease.

Oscar Janiger, a Los Angeles psychotherapist, was the first person to study the effects of LSD on a wide range of people not suffering from any particular psychological problem. Janiger’s approach was very largely nondirective: the setting was a ground floor flat, part of which was a well-equipped art studio for anyone who wanted to paint (Janiger was especially interested in the drug’s effects on creativity), a comfortable modern living room with a record player for anyone who had brought music they wanted to listen to, and French windows giving on to a secluded garden for those who wanted to sit quietly on their own. You could take a walk through the neighborhood so long as you were accompanied by a member of the staff.

The emphasis Janiger put on painting, and on studying the effects of LSD on creativity more generally, indicates how far the drug had already slipped from psychiatric control. LSD was being taken up by avant-garde artists and intellectuals. At first by painters amazed by what the drug could do to form and color; then by writers, musicians, and philosophers equally astounded what high doses could do to cognition.

Mescaline, which had hung fire since its synthesis just after the First World War, was found to resemble LSD very closely in its effects, and for several years the two drugs were used almost interchangeably. As a consequence the peyote cactus cult of the Indians of the American Southwest was suddenly treated with new respect, and the anthropological dimension to hallucinatory drug use began to open up. Gordon Wasson, a New York banker, and his wife, Valentina, tracked down a functioning magic mushroom cult of what seemed great antiquity deep in the mountains of Mexico. Could hallucinatory drugs have played a much more dynamic role in tribal religions and primitive societies in general than had been previously imagined? The word “psychedelic” entered the language.

In fact it was mescaline rather than LSD that proved the inspiration for what was to become the most famous of all testimonials to psychedelics, Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception.

Little more than a lengthy essay, the book opens one May morning in 1953 with Aldous Huxley being given four hundred milligrams of mescaline sulfate by Humphry Osmond, an English doctor responsible for much of the research into LSD and alcoholism in Canada.

Huxley was at his home in the Los Angeles hills, and having taken his dose he lay down and closed his eyes. All he had read about mescaline’s effects led him to expect that within half an hour or so he would begin to see shifting geometric patterns in brilliant color, which would then gradually transform into fantastic landscapes and jeweled architecture. However, as time passed no such thing took place; there were a few colored shapes, but they were devoid of interest. Not until he opened his eyes and sat up did the drug kick in.

Huxley found himself sitting in a transfigured room. Furniture and walls of books were glowing as though lit from within. The jewellike colors for which mescaline was celebrated were there . . . not inside, but out. The spines of the books glowing, he wrote, like rubies and emeralds and lapis lazuli; and when he looked down at his own body, the very material of his trousers had become a source of wonder.

Beside him was a small vase with three flowers in it, a casual combination of a rose, a carnation, and an iris, but what he saw took his breath away:

I was seeing what Adam had seen on the morning of his creation--the miracle, moment by moment, of naked existence . . . Flowers shining with their own inner light and all but quivering under the pressure of the significance with which they were charged . . .

World authority on comparative religion and leading exponent of Indian advaita vedanta Huxley may well have been--but nothing had prepared him for this, this beauty of everyday objects that led him deeper and deeper into is-ness. Perhaps that was the most striking thing The Doors of Perception did, it replaced the concept of hallucination by that of vision:

What rose and iris and carnation so intensely signified was nothing more, and nothing less, than what they were--a transience that was yet eternal life--a perpetual perishing that was at the same time pure Being, a bundle of minute, unique particulars in which, by some unspeakable and yet self-evident paradox, was to be seen the divine source of all existence.

Equally important was that Huxley was the first person to point to boundary loss as being the keynote psychedelic experience. He noted the way the grid that the mind or ego imposes on perception loosens and dissolves, the way phenomena breathe and pulse as they lead you deeper and deeper into themselves. In many ways Huxley’s experience that spring day was more typically Platonic than Indian advaitin. Beauty dissolved into is-ness, and is-ness into intelligible Being.

The Doors of Perception

What no one dreamed was that the drug was about to become part of the roller coaster political ride of the 1960s. The first step toward this happening was that the drug began to break free of doctors and psychoanalysts. For during the early 1960s, LSD was still perfectly legal and, providing you had halfway reasonable professional qualifications, independent research projects could be set up with relative ease.

Oscar Janiger, a Los Angeles psychotherapist, was the first person to study the effects of LSD on a wide range of people not suffering from any particular psychological problem. Janiger’s approach was very largely nondirective: the setting was a ground floor flat, part of which was a well-equipped art studio for anyone who wanted to paint (Janiger was especially interested in the drug’s effects on creativity), a comfortable modern living room with a record player for anyone who had brought music they wanted to listen to, and French windows giving on to a secluded garden for those who wanted to sit quietly on their own. You could take a walk through the neighborhood so long as you were accompanied by a member of the staff.

The emphasis Janiger put on painting, and on studying the effects of LSD on creativity more generally, indicates how far the drug had already slipped from psychiatric control. LSD was being taken up by avant-garde artists and intellectuals. At first by painters amazed by what the drug could do to form and color; then by writers, musicians, and philosophers equally astounded what high doses could do to cognition.

Mescaline, which had hung fire since its synthesis just after the First World War, was found to resemble LSD very closely in its effects, and for several years the two drugs were used almost interchangeably. As a consequence the peyote cactus cult of the Indians of the American Southwest was suddenly treated with new respect, and the anthropological dimension to hallucinatory drug use began to open up. Gordon Wasson, a New York banker, and his wife, Valentina, tracked down a functioning magic mushroom cult of what seemed great antiquity deep in the mountains of Mexico. Could hallucinatory drugs have played a much more dynamic role in tribal religions and primitive societies in general than had been previously imagined? The word “psychedelic” entered the language.

In fact it was mescaline rather than LSD that proved the inspiration for what was to become the most famous of all testimonials to psychedelics, Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception.

Little more than a lengthy essay, the book opens one May morning in 1953 with Aldous Huxley being given four hundred milligrams of mescaline sulfate by Humphry Osmond, an English doctor responsible for much of the research into LSD and alcoholism in Canada.

Huxley was at his home in the Los Angeles hills, and having taken his dose he lay down and closed his eyes. All he had read about mescaline’s effects led him to expect that within half an hour or so he would begin to see shifting geometric patterns in brilliant color, which would then gradually transform into fantastic landscapes and jeweled architecture. However, as time passed no such thing took place; there were a few colored shapes, but they were devoid of interest. Not until he opened his eyes and sat up did the drug kick in.

Huxley found himself sitting in a transfigured room. Furniture and walls of books were glowing as though lit from within. The jewellike colors for which mescaline was celebrated were there . . . not inside, but out. The spines of the books glowing, he wrote, like rubies and emeralds and lapis lazuli; and when he looked down at his own body, the very material of his trousers had become a source of wonder.

Beside him was a small vase with three flowers in it, a casual combination of a rose, a carnation, and an iris, but what he saw took his breath away:

I was seeing what Adam had seen on the morning of his creation--the miracle, moment by moment, of naked existence . . . Flowers shining with their own inner light and all but quivering under the pressure of the significance with which they were charged . . .

World authority on comparative religion and leading exponent of Indian advaita vedanta Huxley may well have been--but nothing had prepared him for this, this beauty of everyday objects that led him deeper and deeper into is-ness. Perhaps that was the most striking thing The Doors of Perception did, it replaced the concept of hallucination by that of vision:

What rose and iris and carnation so intensely signified was nothing more, and nothing less, than what they were--a transience that was yet eternal life--a perpetual perishing that was at the same time pure Being, a bundle of minute, unique particulars in which, by some unspeakable and yet self-evident paradox, was to be seen the divine source of all existence.

Equally important was that Huxley was the first person to point to boundary loss as being the keynote psychedelic experience. He noted the way the grid that the mind or ego imposes on perception loosens and dissolves, the way phenomena breathe and pulse as they lead you deeper and deeper into themselves. In many ways Huxley’s experience that spring day was more typically Platonic than Indian advaitin. Beauty dissolved into is-ness, and is-ness into intelligible Being.

Cuprins

Preface

1 Batch 25

2 Wonder Drug

3 The Doors of Perception

4 Psychopolitics and the Sixties

5 Bad Trips

6 The First Maps

7 Sleep--and Waking Up

8 Realms of the Human Unconscious

9 Session 1: A Low-Dose Trip

10 The First Group of Trips

11 Session 6: Doubling the Dose

12 BPM 2

13 Session 8: Windle Hey

14 Session 9: Mum

15 Underground Psychotherapy

16 Set, Setting, and History

17 God as Light

18 “I Saw a Man Cloathed with Raggs . . .”

19 Resistance

20 Psychedelics Since the Sixties

21 Resistance (continued)

22 Anna and A Cappella

23 Anna’s Death

24 Session 21: Being Two People Simultaneously

25 The Transpersonal

26 Tripping on the Heath

27 The Purple Flowers

28 “Ecstatic Journey of the Living into the Realm of the Dead . . .”

29 “Ecstatic Journey . . .” (continued)

30 Terrible Beauty

31 “Not the true samadhi . . .”

32 Session 27: Last Trip in the Woods

33 Demonstrations, Ecstasy, Advaita

34 Return of the Repressed

35 “Another World Is Possible”

36 “Another World Is Possible” (continued)

37 Toward a Sacramental Vision of Reality

38 Meltdown in God

39 Out of the Body?

40 Session 45: At Judges Walk

41 BPM 4

42 The Long Flashback

43 Interim Report

44 Interim Report (continued)

45 Mutual Immanence

46 Sanctus

Appendix: Ergot and the West

Notes

Bibliography: A Chronology of Psychedelic

Literature

1 Batch 25

2 Wonder Drug

3 The Doors of Perception

4 Psychopolitics and the Sixties

5 Bad Trips

6 The First Maps

7 Sleep--and Waking Up

8 Realms of the Human Unconscious

9 Session 1: A Low-Dose Trip

10 The First Group of Trips

11 Session 6: Doubling the Dose

12 BPM 2

13 Session 8: Windle Hey

14 Session 9: Mum

15 Underground Psychotherapy

16 Set, Setting, and History

17 God as Light

18 “I Saw a Man Cloathed with Raggs . . .”

19 Resistance

20 Psychedelics Since the Sixties

21 Resistance (continued)

22 Anna and A Cappella

23 Anna’s Death

24 Session 21: Being Two People Simultaneously

25 The Transpersonal

26 Tripping on the Heath

27 The Purple Flowers

28 “Ecstatic Journey of the Living into the Realm of the Dead . . .”

29 “Ecstatic Journey . . .” (continued)

30 Terrible Beauty

31 “Not the true samadhi . . .”

32 Session 27: Last Trip in the Woods

33 Demonstrations, Ecstasy, Advaita

34 Return of the Repressed

35 “Another World Is Possible”

36 “Another World Is Possible” (continued)

37 Toward a Sacramental Vision of Reality

38 Meltdown in God

39 Out of the Body?

40 Session 45: At Judges Walk

41 BPM 4

42 The Long Flashback

43 Interim Report

44 Interim Report (continued)

45 Mutual Immanence

46 Sanctus

Appendix: Ergot and the West

Notes

Bibliography: A Chronology of Psychedelic

Literature

Recenzii

"Truly The Acid Diaries is a return to form for psychedelic literature, not only is it a beautifully written narrative but it's full of engaging ideas that Gray uses to weave a web of possibility and, ultimately, hope for the future of psychedelics."

“For anyone who thinks the story of LSD was written in the sixties: think again. The Acid Diaries combines a sharp critique of that decade’s psychedelic adventures with a brave and original series of self-experiments in the present day. The result is an instant classic of acid literature.”

“Read this book.”

“A unique account of a courageous psychonaut’s journey into the preternatural depths of human consciousness.”

“The Acid Diaries is the best insider’s portrait of the psychedelic journey I’ve ever found; the writing is stunningly beautiful in its effervescent candor. The Acid Diaries is an exceptionally honest and unguarded book.”

“Instant enlightenment? Hardly. One has to work for it, as outlined in this book . . . highly recommended . . .”

“Like any strong acid trip, there is both existential angst and cosmic bliss, and many states in between. The Acid Diaries is a contemporary classic of personal psychedelic exploration.”

“All psychonauts will admire and profit from this amazing gift.”

“. . . a rich, dense, philosophical, and psychological trip memoir.”

“If you have any interest at all in acid, then get your hands on this book!”

" . . . extraordinarily insightful..."

“It is Gray’s foundation in spiritual practices that makes The Acid Diaries glow. . . Gray is not some detached scientist. Nor is he some drugged our hippie. He writes with an intelligent, literate and confessional voice that’s casual, yet never sloppy. . . This makes The Acid Diaries an excellent “gateway” book into the genre of psychedelic literature for anyone new to the field.”

“For anyone who thinks the story of LSD was written in the sixties: think again. The Acid Diaries combines a sharp critique of that decade’s psychedelic adventures with a brave and original series of self-experiments in the present day. The result is an instant classic of acid literature.”

“Read this book.”

“A unique account of a courageous psychonaut’s journey into the preternatural depths of human consciousness.”

“The Acid Diaries is the best insider’s portrait of the psychedelic journey I’ve ever found; the writing is stunningly beautiful in its effervescent candor. The Acid Diaries is an exceptionally honest and unguarded book.”

“Instant enlightenment? Hardly. One has to work for it, as outlined in this book . . . highly recommended . . .”

“Like any strong acid trip, there is both existential angst and cosmic bliss, and many states in between. The Acid Diaries is a contemporary classic of personal psychedelic exploration.”

“All psychonauts will admire and profit from this amazing gift.”

“. . . a rich, dense, philosophical, and psychological trip memoir.”

“If you have any interest at all in acid, then get your hands on this book!”

" . . . extraordinarily insightful..."

“It is Gray’s foundation in spiritual practices that makes The Acid Diaries glow. . . Gray is not some detached scientist. Nor is he some drugged our hippie. He writes with an intelligent, literate and confessional voice that’s casual, yet never sloppy. . . This makes The Acid Diaries an excellent “gateway” book into the genre of psychedelic literature for anyone new to the field.”

Descriere

An exploration of the personal and spiritual truths revealed through LSD.