The Age of Empathy: Nature's Lessons for a Kinder Society

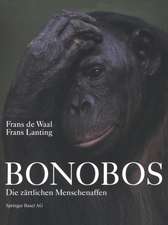

Autor Frans de Waal, F. B. M. De Waalen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2010

—Desmond Morris, author of The Naked Ape

Are we our brothers' keepers? Do we have an instinct for compassion? Or are we, as is often assumed, only on earth to serve our own survival and interests? In this thought-provoking book, the acclaimed author of Our Inner Ape examines how empathy comes naturally to a great variety of animals, including humans.

By studying social behaviors in animals, such as bonding, the herd instinct, the forming of trusting alliances, expressions of consolation, and conflict resolution, Frans de Waal demonstrates that animalsߝand humansߝare "preprogrammed to reach out." He has found that chimpanzees care for mates that are wounded by leopards, elephants offer "reassuring rumbles" to youngsters in distress, and dolphins support sick companions near the water's surface to prevent them from drowning. From day one humans have innate sensitivities to faces, bodies, and voices; we've been designed to feel for one another.

De Waal's theory runs counter to the assumption that humans are inherently selfish, which can be seen in the fields of politics, law, and finance, and whichseems to be evidenced by the current greed-driven stock market collapse. But he cites the public's outrage at the U.S. government's lack of empathy in the wake of Hurricane Katrina as a significant shift in perspectiveߝone that helped Barack Obama become elected and ushered in what may well become an Age of Empathy. Through a better understanding of empathy's survival value in evolution, de Waal suggests, we can work together toward a more just society based on a more generous and accurate view of human nature.

Written in layman's prose with a wealth of anecdotes, wry humor, and incisive intelligence, The Age of Empathy is essential reading for our embattled times.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 116.57 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 175

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.31€ • 23.29$ • 18.46£

22.31€ • 23.29$ • 18.46£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307407771

ISBN-10: 0307407772

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 145 x 213 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0307407772

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 145 x 213 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Recenzii

"A pioneer in primate studies, Frans de Waal sees our better side in chimps, especially our capacity for empathy. In his research, Dr. de Waal has gathered ample evidence that our ability to identify with another's distress -- a catalyst for compassion and charity -- has deep roots in the origin of our species. It is a view independently reinforced by recent biomedical studies showing that our brains are built to feel another's pain."

—Robert Lee Hotz, The Wall Street Journal

“It’s hard to feel the pain of the next guy. First, you have to notice that he exists…then realize that he has different thoughts than you…and different emotions…and that he needs help…and that you should help because you’d like the same done for you…and, wait, did I remember to lock the car?…and… Empathy is often viewed as requiring cognitive capacities for things like theory of mind, perspective taking and the golden rule, implying that empathy is pretty much limited to humans, and is a fairly fragile phenomenon in us. For decades, Frans de Waal has generated elegant data and thinking that show that this is wrong. In this superb book, he shows how we are not the only species with elements of those cognitive capacities, empathy is as much about affect as cognition, and our empathic humanity has roots far deeper than our human-ness.”

—Robert Sapolsky, author of Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers and A Primate’s Memoir

"The lessons of the economic meltdown, Hurricane Katrina, and other disasters may not be what you think: Biologically, humans are not selfish animals. For that matter, neither are animals, writes the engaging Frans de Waal, a psychology professor with proof positive that, like other creatures who hang out in herds, we've evolved to be empathetic. We don't just hear a scream, it chills us to the bone; when we see a smile, we answer with one of our own. THE AGE OF EMPATHY offers advice to cutthroat so-called realists: Listen to your inner ape."

—O, The Oprah Magazine

"Freshly topical….a corrective to the idea that all animals—human and otherwise—are selfish and unfeeling to the core."

—The Economist

"Without question, de Waal’s essential findings should become part of mainstream conversation. But we need to go further by joining them with a radical political analysis, one that spells out the cultural mechanisms that give rise to an empathy-deficient society. Only then can we reclaim the continuity of morality that emerges so eloquently from these pages."

—Gary Olson, The Baltimore Chronicle

"De Waal, a renowned primatologist, knows the territory firsthand. He writes clearly and plays fair; he takes on the strongest arguments against him and is quick to acknowledge complexity. His book is popular science as it should be, far superior to the recent spate of “Darwin made me do it” books that purport to explain (or explain away) our behavior."

—Edward Dolnick, Bookforum

"De Waal is an excellent tour guide, refreshingly literate outside his field, deft at stitching bits of philosophy and anthropology into the narrative. He is also pleasingly opinionated; he seems to have columnist aspirations of his own, and his frequent ߝ usually thoughtful and balanced, occasionally facile ߝ digressions on morality and U.S. politics read like boilerplate New York Times editorials.

Empathy, de Waal says, is one of our most innate capacities, one that likely evolved from mammalian parental care. It begins in the body, a deep unconscious synchrony between mother and child that sets the tone for so many mammalian interactions. When someone smiles, we smile; when they yawn, we yawn; emotion is contagious."

—Jeff Warren, Globe & Mail

"Given the nature of business survival in a competitive world, de Waal's clarion call that greed is out and empathy is in, may be a call we should all hear."

—Ray Wlliams, Psychology Today

"If Dawkins is Huxley’s intellectual descendant, de Waal is certainly Kropotkin’s. Whereas Dawkins holds that biology will be of little help in building a just society, de Waal is less convinced that we are at war with our nature. Rather, he finds it odd that those instances of spontaneous altruism shown in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks or during the Katrina disaster could somehow be considered unnatural."

—Eric Michael Johnson, SEED

"The endeavor has majesty. It also affirms a very unmajestic human experience: Our emotions are a mess. Of course they are—they are accumulated bits of psychic life thrown together over millions of years by evolution with no oversight or quality control about what they actually feel like. Just because we have a single word for a feeling or trait now doesn't mean that it is homogenous or discrete.

Developing an appreciation of this complexity, de Waal suggests, could actually combat one of the least helpful of human tendencies: the impulse—not innate but socially very contagious—to reductively assume our biology is bad."

—Christine Kenneally, Slate

"De Waal...culls an astounding volume of research that deflates the human assumption that animals lack the characteristics often referred to as 'humane.' He cites recent animal behavior studies that challenge the 'primacy of human logic' and put animals on a closer behavioral footing with humans.....Throughout the book, de Waal illustrates how behaving more like our wild mammalian cousins may just save humanity. His contention, colored by philosophical musings and fascinating anecdotes of observed emotional connections between animals, argues persuasively that humans are not greedy or belligerent because animals are; such traits are far from organic or inevitable but patently manmade."

—Publisher's Weekly

"Addressing the question of whether it is possible to 'combine a thriving economy with a humane society' zoologist de Waal answers with a resounding yes....De Waal cites the 'evolutionary antiquity' of empathy to argue that 'society depends on a second invisible hand, one that reaches out to others.' An appealing celebration of our better nature."

—Kirkus

"[De Waal's] illuminating description and explanation of his research have made progressively more magnetic reading (and viewing of the exceptionally illustrative photos and drawings) of eight previous books and don't fail him now."

—Booklist

Praise for Our Inner Ape by Frans de Waal

"This important and illuminating book should help our own species take that lesson in civility to heart."

—Temple Grandin, New York Times

"Frans de Waal's work . . . has helped lift Darwin's conjectures about the evolution of morality to a new level."

—Jonathan Weiner, author of The Beak of the Finch

"Frans de Waal has achieved that state of grace for a scientistߝdoing research that is both rigorous and wildly creative, and in the process has redefined how we think about the most interesting realms of behavior among nonhuman primatesߝcooperation, reconciliation, a sense of fairness, and even the rudiments of morality."

—Robert M. Sapolsky, author of Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers and A Primate's Memoir

"Frans de Waal is uniquely placed to write a book on the duality of human nature and on its biological origins in other primate species. No other book has attempted to cover this ground. Few topics are as timely to the understanding of the human mind and behavior."

—Antonio Damasio, author of Descartes' Error

"On the basis of a fascinating and provocative account of the remarkable continuities between the social emotions of humans and of nonhuman primates, de Waal develops a compelling case for the evolutionary roots of human morality."

—Harry G. Frankfurt, author of On Bullshit

From the Hardcover edition.

—Robert Lee Hotz, The Wall Street Journal

“It’s hard to feel the pain of the next guy. First, you have to notice that he exists…then realize that he has different thoughts than you…and different emotions…and that he needs help…and that you should help because you’d like the same done for you…and, wait, did I remember to lock the car?…and… Empathy is often viewed as requiring cognitive capacities for things like theory of mind, perspective taking and the golden rule, implying that empathy is pretty much limited to humans, and is a fairly fragile phenomenon in us. For decades, Frans de Waal has generated elegant data and thinking that show that this is wrong. In this superb book, he shows how we are not the only species with elements of those cognitive capacities, empathy is as much about affect as cognition, and our empathic humanity has roots far deeper than our human-ness.”

—Robert Sapolsky, author of Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers and A Primate’s Memoir

"The lessons of the economic meltdown, Hurricane Katrina, and other disasters may not be what you think: Biologically, humans are not selfish animals. For that matter, neither are animals, writes the engaging Frans de Waal, a psychology professor with proof positive that, like other creatures who hang out in herds, we've evolved to be empathetic. We don't just hear a scream, it chills us to the bone; when we see a smile, we answer with one of our own. THE AGE OF EMPATHY offers advice to cutthroat so-called realists: Listen to your inner ape."

—O, The Oprah Magazine

"Freshly topical….a corrective to the idea that all animals—human and otherwise—are selfish and unfeeling to the core."

—The Economist

"Without question, de Waal’s essential findings should become part of mainstream conversation. But we need to go further by joining them with a radical political analysis, one that spells out the cultural mechanisms that give rise to an empathy-deficient society. Only then can we reclaim the continuity of morality that emerges so eloquently from these pages."

—Gary Olson, The Baltimore Chronicle

"De Waal, a renowned primatologist, knows the territory firsthand. He writes clearly and plays fair; he takes on the strongest arguments against him and is quick to acknowledge complexity. His book is popular science as it should be, far superior to the recent spate of “Darwin made me do it” books that purport to explain (or explain away) our behavior."

—Edward Dolnick, Bookforum

"De Waal is an excellent tour guide, refreshingly literate outside his field, deft at stitching bits of philosophy and anthropology into the narrative. He is also pleasingly opinionated; he seems to have columnist aspirations of his own, and his frequent ߝ usually thoughtful and balanced, occasionally facile ߝ digressions on morality and U.S. politics read like boilerplate New York Times editorials.

Empathy, de Waal says, is one of our most innate capacities, one that likely evolved from mammalian parental care. It begins in the body, a deep unconscious synchrony between mother and child that sets the tone for so many mammalian interactions. When someone smiles, we smile; when they yawn, we yawn; emotion is contagious."

—Jeff Warren, Globe & Mail

"Given the nature of business survival in a competitive world, de Waal's clarion call that greed is out and empathy is in, may be a call we should all hear."

—Ray Wlliams, Psychology Today

"If Dawkins is Huxley’s intellectual descendant, de Waal is certainly Kropotkin’s. Whereas Dawkins holds that biology will be of little help in building a just society, de Waal is less convinced that we are at war with our nature. Rather, he finds it odd that those instances of spontaneous altruism shown in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks or during the Katrina disaster could somehow be considered unnatural."

—Eric Michael Johnson, SEED

"The endeavor has majesty. It also affirms a very unmajestic human experience: Our emotions are a mess. Of course they are—they are accumulated bits of psychic life thrown together over millions of years by evolution with no oversight or quality control about what they actually feel like. Just because we have a single word for a feeling or trait now doesn't mean that it is homogenous or discrete.

Developing an appreciation of this complexity, de Waal suggests, could actually combat one of the least helpful of human tendencies: the impulse—not innate but socially very contagious—to reductively assume our biology is bad."

—Christine Kenneally, Slate

"De Waal...culls an astounding volume of research that deflates the human assumption that animals lack the characteristics often referred to as 'humane.' He cites recent animal behavior studies that challenge the 'primacy of human logic' and put animals on a closer behavioral footing with humans.....Throughout the book, de Waal illustrates how behaving more like our wild mammalian cousins may just save humanity. His contention, colored by philosophical musings and fascinating anecdotes of observed emotional connections between animals, argues persuasively that humans are not greedy or belligerent because animals are; such traits are far from organic or inevitable but patently manmade."

—Publisher's Weekly

"Addressing the question of whether it is possible to 'combine a thriving economy with a humane society' zoologist de Waal answers with a resounding yes....De Waal cites the 'evolutionary antiquity' of empathy to argue that 'society depends on a second invisible hand, one that reaches out to others.' An appealing celebration of our better nature."

—Kirkus

"[De Waal's] illuminating description and explanation of his research have made progressively more magnetic reading (and viewing of the exceptionally illustrative photos and drawings) of eight previous books and don't fail him now."

—Booklist

Praise for Our Inner Ape by Frans de Waal

"This important and illuminating book should help our own species take that lesson in civility to heart."

—Temple Grandin, New York Times

"Frans de Waal's work . . . has helped lift Darwin's conjectures about the evolution of morality to a new level."

—Jonathan Weiner, author of The Beak of the Finch

"Frans de Waal has achieved that state of grace for a scientistߝdoing research that is both rigorous and wildly creative, and in the process has redefined how we think about the most interesting realms of behavior among nonhuman primatesߝcooperation, reconciliation, a sense of fairness, and even the rudiments of morality."

—Robert M. Sapolsky, author of Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers and A Primate's Memoir

"Frans de Waal is uniquely placed to write a book on the duality of human nature and on its biological origins in other primate species. No other book has attempted to cover this ground. Few topics are as timely to the understanding of the human mind and behavior."

—Antonio Damasio, author of Descartes' Error

"On the basis of a fascinating and provocative account of the remarkable continuities between the social emotions of humans and of nonhuman primates, de Waal develops a compelling case for the evolutionary roots of human morality."

—Harry G. Frankfurt, author of On Bullshit

From the Hardcover edition.

Notă biografică

FRANS DE WAAL is a Dutch-born biologist who lives and works in Atlanta, Georgia. One of the world's best-known primatologists, de Waal is C. H. Candler professor of psychology and director of the Living Links Center at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center at Emory University. He has been elected to the National Academy of Sciences and the Royal Dutch Academy of Sciences. In 2007, Time selected him as one of the World's 100 Most Influential People.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

1

Biology, Left and Right

What is government itself but the greatest of all

reflections on human nature?

-james madison, 1788

Are we our brothers' keepers? Should we be? Or would this role only interfere with why we are on earth, which according to economists is to consume and produce, and according to biologists is to survive and reproduce? That both views sound similar is logical given that they arose at around the same time, in the same place, during the English Industrial Revolution. Both follow a competition-is-good-for-you logic.

Slightly earlier and slightly to the north, in Scotland, the thinking was different. The father of economics, Adam Smith, understood as no other that the pursuit of self-interest needs to be tempered by "fellow feeling." He said so in The Theory of Moral Sentiments, a book not nearly as popular as his later work The Wealth of Nations. He famously opened his first book with:

How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.

The French revolutionaries chanted of fraternite, Abraham Lincoln appealed to the bonds of sympathy, and Theodore Roosevelt spoke glowingly of fellow feeling as "the most important factor in producing a healthy political and social life." But if this is true, why is this sentiment sometimes ridiculed as being, well, sentimental? A recent example occurred after Hurricane Katrina struck Louisiana in 2005. While the American people were transfixed by the unprecedented catastrophe, one cable news network saw fit to ask if the Constitution actually provides for disaster relief. A guest on the show argued that the misery of others is none of our business.

The day the levees broke, I happened to be driving down from Atlanta to Alabama to give a lecture at Auburn University. Except for a few fallen trees, this part of Alabama had suffered little damage, but the hotel was full of refugees: people had crammed the rooms with grandparents, children, dogs, and cats. I woke up at a zoo! Not the strangest place for a biologist, perhaps, but it conveyed the size of the calamity. And these people were the lucky ones. The morning newspaper at my door screamed, "Why have we been left behind like animals?" a quote from one of the people stuck for days without food and sanitation in the Louisiana Superdome.

I took issue with this headline, not because I felt there was nothing to complain about, but because animals don't necessarily leave one another behind. My lecture was on precisely this topic, on how we have an "inner ape" that is not nearly as callous and nasty as advertised, and how empathy comes naturally to our species. I wasn't claiming that it always finds expression, though. Thousands of people with money and cars had fled New Orleans, leaving the sick, old, and poor to fend for themselves. In some places dead bodies floated in the water, where they were being eaten by alligators.

But immediately following the disaster there was also deep embarrassment in the nation about what had happened, and an incredible outpouring of support. Sympathy was not absent-it just was late in coming. Americans are a generous people, yet raised with the mistaken belief that the "invisible hand" of the free market-a metaphor introduced by the same Adam Smith-will take care of society's woes. The invisible hand, however, did nothing to prevent the appalling survival-of-the-fittest scenes in New Orleans.

The ugly secret of economic success is that it sometimes comes at the expense of public funding, thus creating a giant underclass that no one cares about. Katrina exposed the underbelly of American society. On my drive back to Atlanta, it occurred to me that this is the theme of our time: the common good. We tend to focus on wars, terror threats, globalization, and petty political scandals, yet the larger issue is how to combine a thriving economy with a humane society. It relates to health care, education, justice, and-as illustrated by Katrina-protection against nature. The levees in Louisiana had been criminally neglected. In the weeks following the flooding, the media were busy finger-pointing. Had the engineers been at fault? Had funds been diverted? Shouldn't the president have broken off his vacation? Where I come from, fingers belong in the dike-or at least that's how legend has it. In the Netherlands, much of which lies up to twenty feet below sea level, dikes are so sacred that politicians have literally no say over them: Water management is in the hands of engineers and local citizen boards that predate the nation itself.

Come to think of it, this also reflects a distrust of government, not so much big government but rather the short-sightedness of most politicians.

Evolutionary Spirit

How people organize their societies may not seem the sort of topic a biologist should worry about. I should be concerned with the ivory-billed woodpecker, the role of primates in the spread of AIDS or Ebola, the disappearance of tropical rain forests, or whether we evolved from the apes. Whereas the latter remains an issue for some, there has nevertheless been a dramatic shift in public opinion regarding the role of biology. The days are behind us when E. O. Wilson was showered with cold water after a lecture on the connection between animal and human behavior. Greater openness to parallels with animals makes life easier for the biologist, hence my decision to go to the next level and see if biology can shed light on human society. If this means wading right into political controversy, so be it; it's not as if biology is not already a part of it. Every debate about society and government makes huge assumptions about human nature, which are presented as if they come straight out of biology. But they almost never do.

Lovers of open competition, for example, often invoke evolution. The e-word even slipped into the infamous "greed speech" of Gordon Gekko, the ruthless corporate raider played by Michael Douglas in the 1987 movie Wall Street:

The point is, ladies and gentleman, that "greed"-for lack of a better word-is good. Greed is right. Greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit.

The evolutionary spirit? Why are assumptions about biology always on the negative side? In the social sciences, human nature is typified by the old Hobbesian proverb Homo homini lupus ("Man is wolf to man"), a questionable statement about our own species based on false assumptions about another species. A biologist exploring the interaction between society and human nature really isn't doing anything new, therefore. The only difference is that instead of trying to justify a particular ideological framework, the biologist has an actual interest in the question of what human nature is and where it came from. Is the evolutionary spirit really all about greed, as Gekko claimed, or is there more to it?

Students of law, economics, and politics lack the tools to look at their own society with any objectivity. What are they going to compare it with? They rarely, if ever, consult the vast knowledge of human behavior accumulated in anthropology, psychology, biology, or neuroscience. The short answer derived from the latter disciplines is that we are group animals: highly cooperative, sensitive to injustice, sometimes warmongering, but mostly peace loving. A society that ignores these tendencies can't be optimal. True, we are also incentive-driven animals, focused on status, territory, and food security, so that any society that ignores those tendencies can't be optimal, either. There is both a social and a selfish side to our species. But since the latter is, at least in the West, the dominant assumption, my focus will be on the former: the role of empathy and social connectedness.

There is exciting new research about the origins of altruism and fairness in both ourselves and other animals. For example, if one gives two monkeys hugely different rewards for the same task, the one who gets the short end of the stick simply refuses to perform. In our own species, too, individuals reject income if they feel the distribution is unfair. Since any income should beat none at all, this means that both monkeys and people fail to follow the profit principle to the letter. By protesting against unfairness, their behavior supports both the claim that incentives matter and that there is a natural dislike of injustice.

Yet in some ways we seem to be moving ever closer to a society with no solidarity whatsoever, one in which a lot of people can expect the short end of the stick. To reconcile this trend with good old Christian values, such as care for the sick and poor, may seem hopeless. But one common strategy is to point the finger at the victims. If the poor can be blamed for being poor, everyone else is off the hook. Thus, a year after Katrina, Newt Gingrich, a prominent conservative politician, called for an investigation into "the failure of citizenship" of people who had been unsuccessful escaping from the hurricane.

Those who highlight individual freedom often regard collective interests as a romantic notion, something for sissies and communists. They prefer an every-man-for-himself logic. For example, instead of spending money on levees that protect an entire region, why not let everyone take care of their own safety? A new company in Florida is doing just that, renting out seats on private jets to fly people out of places threatened by hurricanes. This way, those who can afford it won't need to drive out at five miles per hour with the rest of the populace.

Every society has to deal with this me-first attitude. I see it play out every day. And here I am not referring to people, but to chimpanzees at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center, where I work. At our field station northeast of Atlanta, we house chimps in large outdoor corrals, sometimes providing them with shareable food, such as watermelons. Most of the apes want to be the first to put their hands on our food, because once they have it, it's rarely taken away by others. There actually exists respect of ownership, so that even the lowest-ranking female is allowed to keep her food by the most dominant male. Food possessors are often approached by others with an outstretched hand (a gesture that is also the universal way humans ask for a handout). The apes beg and whine, literally whimpering in the face of the other. If the possessor doesn't give in, beggars may throw a fit, screaming and rolling around as if the world is coming to an end.

My point is that there is both ownership and sharing. In the end, usually within twenty minutes, all of the chimpanzees in the group will have some food. Owners share with their best buddies and family, who in turn share with their best buddies and family. It is a rather peaceful scene even though there is also quite a bit of jostling for position. I still remember a camera crew filming a sharing session and the cameraman turning to me and saying, "I should show this to my kids. They could learn from it."

So, don't believe anyone who says that since nature is based on a struggle for life, we need to live like this as well. Many animals survive not by eliminating each other or keeping everything for themselves, but by cooperating and sharing. This applies most definitely to pack hunters, such as wolves or killer whales, but also to our closest relatives, the primates. In a study done at Ta• National Park, in Ivory Coast, chimpanzees took care of group mates wounded by leopards; they licked their mates' blood, carefully removed dirt, and waved away flies that came near the wounds. They protected injured companions and slowed down during travel in order to accommodate them. All of this makes perfect sense, given that chimpanzees live in groups for a reason, the same way wolves and humans are group animals for a reason. If man is wolf to man, he is so in every sense, not just the negative one. We would not be where we are today had our ancestors been socially aloof.

What we need is a complete overhaul of assumptions about human nature. Too many economists and politicians model human society on the perpetual struggle they believe exists in nature, but which is a mere projection. Like magicians, they first throw their ideological prejudices into the hat of nature, then pull them out by their very ears to show how much nature agrees with them. It's a trick we have fallen for for too long. Obviously, competition is part of the picture, but humans can't live by competition alone.

The Over-kissed Child

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant saw as little value in human kindness as former U.S. vice president Dick Cheney did in energy conservation. Cheney mocked conservation as "a sign of personal virtue" that, sadly, wouldn't do the planet any good. Kant praised compassion as "beautiful" yet considered it irrelevant to a virtuous life. Who needs tender feelings if duty is all that matters?

We live in an age that celebrates the cerebral and looks down upon emotions as mushy and messy. Worse, emotions are hard to control, and isn't self-control what makes us human? Like hermits resisting life's temptations, modern philosophers try to keep human passions at arm's length and focus on logic and reason instead. But just as no hermit can avoid dreaming of pretty maidens and good meals, no philosopher can get around the basic needs, desires, and obsessions of a species that, unfortunately for them, actually is made of flesh and blood. The notion of "pure reason" is pure fiction.

If morality is derived from abstract principles, why do judgments often come instantaneously? We hardly need to think about them. In fact, psychologist Jonathan Haidt believes we arrive at them intuitively. He presented human subjects with stories of odd behavior (such as a one-night stand between a brother and sister), which the subjects immediately disapproved of. He then challenged every single reason they could come up with for their rejection of incest until his subjects ran out of reasons. They might say that incest leads to abnormal offspring, but in Haidt's story the siblings used effective contraception, which took care of this argument. Most of his subjects quickly reached the stage of "moral dumbfounding": They stubbornly insisted the behavior was wrong without being able to say why.

From the Hardcover edition.

Biology, Left and Right

What is government itself but the greatest of all

reflections on human nature?

-james madison, 1788

Are we our brothers' keepers? Should we be? Or would this role only interfere with why we are on earth, which according to economists is to consume and produce, and according to biologists is to survive and reproduce? That both views sound similar is logical given that they arose at around the same time, in the same place, during the English Industrial Revolution. Both follow a competition-is-good-for-you logic.

Slightly earlier and slightly to the north, in Scotland, the thinking was different. The father of economics, Adam Smith, understood as no other that the pursuit of self-interest needs to be tempered by "fellow feeling." He said so in The Theory of Moral Sentiments, a book not nearly as popular as his later work The Wealth of Nations. He famously opened his first book with:

How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.

The French revolutionaries chanted of fraternite, Abraham Lincoln appealed to the bonds of sympathy, and Theodore Roosevelt spoke glowingly of fellow feeling as "the most important factor in producing a healthy political and social life." But if this is true, why is this sentiment sometimes ridiculed as being, well, sentimental? A recent example occurred after Hurricane Katrina struck Louisiana in 2005. While the American people were transfixed by the unprecedented catastrophe, one cable news network saw fit to ask if the Constitution actually provides for disaster relief. A guest on the show argued that the misery of others is none of our business.

The day the levees broke, I happened to be driving down from Atlanta to Alabama to give a lecture at Auburn University. Except for a few fallen trees, this part of Alabama had suffered little damage, but the hotel was full of refugees: people had crammed the rooms with grandparents, children, dogs, and cats. I woke up at a zoo! Not the strangest place for a biologist, perhaps, but it conveyed the size of the calamity. And these people were the lucky ones. The morning newspaper at my door screamed, "Why have we been left behind like animals?" a quote from one of the people stuck for days without food and sanitation in the Louisiana Superdome.

I took issue with this headline, not because I felt there was nothing to complain about, but because animals don't necessarily leave one another behind. My lecture was on precisely this topic, on how we have an "inner ape" that is not nearly as callous and nasty as advertised, and how empathy comes naturally to our species. I wasn't claiming that it always finds expression, though. Thousands of people with money and cars had fled New Orleans, leaving the sick, old, and poor to fend for themselves. In some places dead bodies floated in the water, where they were being eaten by alligators.

But immediately following the disaster there was also deep embarrassment in the nation about what had happened, and an incredible outpouring of support. Sympathy was not absent-it just was late in coming. Americans are a generous people, yet raised with the mistaken belief that the "invisible hand" of the free market-a metaphor introduced by the same Adam Smith-will take care of society's woes. The invisible hand, however, did nothing to prevent the appalling survival-of-the-fittest scenes in New Orleans.

The ugly secret of economic success is that it sometimes comes at the expense of public funding, thus creating a giant underclass that no one cares about. Katrina exposed the underbelly of American society. On my drive back to Atlanta, it occurred to me that this is the theme of our time: the common good. We tend to focus on wars, terror threats, globalization, and petty political scandals, yet the larger issue is how to combine a thriving economy with a humane society. It relates to health care, education, justice, and-as illustrated by Katrina-protection against nature. The levees in Louisiana had been criminally neglected. In the weeks following the flooding, the media were busy finger-pointing. Had the engineers been at fault? Had funds been diverted? Shouldn't the president have broken off his vacation? Where I come from, fingers belong in the dike-or at least that's how legend has it. In the Netherlands, much of which lies up to twenty feet below sea level, dikes are so sacred that politicians have literally no say over them: Water management is in the hands of engineers and local citizen boards that predate the nation itself.

Come to think of it, this also reflects a distrust of government, not so much big government but rather the short-sightedness of most politicians.

Evolutionary Spirit

How people organize their societies may not seem the sort of topic a biologist should worry about. I should be concerned with the ivory-billed woodpecker, the role of primates in the spread of AIDS or Ebola, the disappearance of tropical rain forests, or whether we evolved from the apes. Whereas the latter remains an issue for some, there has nevertheless been a dramatic shift in public opinion regarding the role of biology. The days are behind us when E. O. Wilson was showered with cold water after a lecture on the connection between animal and human behavior. Greater openness to parallels with animals makes life easier for the biologist, hence my decision to go to the next level and see if biology can shed light on human society. If this means wading right into political controversy, so be it; it's not as if biology is not already a part of it. Every debate about society and government makes huge assumptions about human nature, which are presented as if they come straight out of biology. But they almost never do.

Lovers of open competition, for example, often invoke evolution. The e-word even slipped into the infamous "greed speech" of Gordon Gekko, the ruthless corporate raider played by Michael Douglas in the 1987 movie Wall Street:

The point is, ladies and gentleman, that "greed"-for lack of a better word-is good. Greed is right. Greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit.

The evolutionary spirit? Why are assumptions about biology always on the negative side? In the social sciences, human nature is typified by the old Hobbesian proverb Homo homini lupus ("Man is wolf to man"), a questionable statement about our own species based on false assumptions about another species. A biologist exploring the interaction between society and human nature really isn't doing anything new, therefore. The only difference is that instead of trying to justify a particular ideological framework, the biologist has an actual interest in the question of what human nature is and where it came from. Is the evolutionary spirit really all about greed, as Gekko claimed, or is there more to it?

Students of law, economics, and politics lack the tools to look at their own society with any objectivity. What are they going to compare it with? They rarely, if ever, consult the vast knowledge of human behavior accumulated in anthropology, psychology, biology, or neuroscience. The short answer derived from the latter disciplines is that we are group animals: highly cooperative, sensitive to injustice, sometimes warmongering, but mostly peace loving. A society that ignores these tendencies can't be optimal. True, we are also incentive-driven animals, focused on status, territory, and food security, so that any society that ignores those tendencies can't be optimal, either. There is both a social and a selfish side to our species. But since the latter is, at least in the West, the dominant assumption, my focus will be on the former: the role of empathy and social connectedness.

There is exciting new research about the origins of altruism and fairness in both ourselves and other animals. For example, if one gives two monkeys hugely different rewards for the same task, the one who gets the short end of the stick simply refuses to perform. In our own species, too, individuals reject income if they feel the distribution is unfair. Since any income should beat none at all, this means that both monkeys and people fail to follow the profit principle to the letter. By protesting against unfairness, their behavior supports both the claim that incentives matter and that there is a natural dislike of injustice.

Yet in some ways we seem to be moving ever closer to a society with no solidarity whatsoever, one in which a lot of people can expect the short end of the stick. To reconcile this trend with good old Christian values, such as care for the sick and poor, may seem hopeless. But one common strategy is to point the finger at the victims. If the poor can be blamed for being poor, everyone else is off the hook. Thus, a year after Katrina, Newt Gingrich, a prominent conservative politician, called for an investigation into "the failure of citizenship" of people who had been unsuccessful escaping from the hurricane.

Those who highlight individual freedom often regard collective interests as a romantic notion, something for sissies and communists. They prefer an every-man-for-himself logic. For example, instead of spending money on levees that protect an entire region, why not let everyone take care of their own safety? A new company in Florida is doing just that, renting out seats on private jets to fly people out of places threatened by hurricanes. This way, those who can afford it won't need to drive out at five miles per hour with the rest of the populace.

Every society has to deal with this me-first attitude. I see it play out every day. And here I am not referring to people, but to chimpanzees at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center, where I work. At our field station northeast of Atlanta, we house chimps in large outdoor corrals, sometimes providing them with shareable food, such as watermelons. Most of the apes want to be the first to put their hands on our food, because once they have it, it's rarely taken away by others. There actually exists respect of ownership, so that even the lowest-ranking female is allowed to keep her food by the most dominant male. Food possessors are often approached by others with an outstretched hand (a gesture that is also the universal way humans ask for a handout). The apes beg and whine, literally whimpering in the face of the other. If the possessor doesn't give in, beggars may throw a fit, screaming and rolling around as if the world is coming to an end.

My point is that there is both ownership and sharing. In the end, usually within twenty minutes, all of the chimpanzees in the group will have some food. Owners share with their best buddies and family, who in turn share with their best buddies and family. It is a rather peaceful scene even though there is also quite a bit of jostling for position. I still remember a camera crew filming a sharing session and the cameraman turning to me and saying, "I should show this to my kids. They could learn from it."

So, don't believe anyone who says that since nature is based on a struggle for life, we need to live like this as well. Many animals survive not by eliminating each other or keeping everything for themselves, but by cooperating and sharing. This applies most definitely to pack hunters, such as wolves or killer whales, but also to our closest relatives, the primates. In a study done at Ta• National Park, in Ivory Coast, chimpanzees took care of group mates wounded by leopards; they licked their mates' blood, carefully removed dirt, and waved away flies that came near the wounds. They protected injured companions and slowed down during travel in order to accommodate them. All of this makes perfect sense, given that chimpanzees live in groups for a reason, the same way wolves and humans are group animals for a reason. If man is wolf to man, he is so in every sense, not just the negative one. We would not be where we are today had our ancestors been socially aloof.

What we need is a complete overhaul of assumptions about human nature. Too many economists and politicians model human society on the perpetual struggle they believe exists in nature, but which is a mere projection. Like magicians, they first throw their ideological prejudices into the hat of nature, then pull them out by their very ears to show how much nature agrees with them. It's a trick we have fallen for for too long. Obviously, competition is part of the picture, but humans can't live by competition alone.

The Over-kissed Child

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant saw as little value in human kindness as former U.S. vice president Dick Cheney did in energy conservation. Cheney mocked conservation as "a sign of personal virtue" that, sadly, wouldn't do the planet any good. Kant praised compassion as "beautiful" yet considered it irrelevant to a virtuous life. Who needs tender feelings if duty is all that matters?

We live in an age that celebrates the cerebral and looks down upon emotions as mushy and messy. Worse, emotions are hard to control, and isn't self-control what makes us human? Like hermits resisting life's temptations, modern philosophers try to keep human passions at arm's length and focus on logic and reason instead. But just as no hermit can avoid dreaming of pretty maidens and good meals, no philosopher can get around the basic needs, desires, and obsessions of a species that, unfortunately for them, actually is made of flesh and blood. The notion of "pure reason" is pure fiction.

If morality is derived from abstract principles, why do judgments often come instantaneously? We hardly need to think about them. In fact, psychologist Jonathan Haidt believes we arrive at them intuitively. He presented human subjects with stories of odd behavior (such as a one-night stand between a brother and sister), which the subjects immediately disapproved of. He then challenged every single reason they could come up with for their rejection of incest until his subjects ran out of reasons. They might say that incest leads to abnormal offspring, but in Haidt's story the siblings used effective contraception, which took care of this argument. Most of his subjects quickly reached the stage of "moral dumbfounding": They stubbornly insisted the behavior was wrong without being able to say why.

From the Hardcover edition.