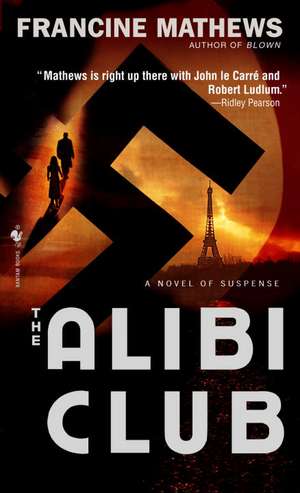

The Alibi Club

Autor Francine Mathewsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2007

As the Nazis march on Paris and the crisis escalates, four remarkable characters are swept into the maelstrom. Their courage will change the course of history.

Epic and yet intimate, a seamless blend of fact and fiction based on a little-known episode of the war, The Alibi Club is a thriller of fierce and complex suspense by a writer whose own life in the spy world makes espionage come uniquely alive.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 46.53 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 70

Preț estimativ în valută:

8.91€ • 9.68$ • 7.49£

8.91€ • 9.68$ • 7.49£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553586305

ISBN-10: 0553586300

Pagini: 370

Dimensiuni: 108 x 175 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Bantam Books

ISBN-10: 0553586300

Pagini: 370

Dimensiuni: 108 x 175 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Bantam Books

Notă biografică

Francine Mattews has worked as a foreign-policy analyst for the CIA. She is the author of The Cutout, which has been purchased for a major motion picture by Warner Bros.; The Secret Agent; and Blown. Under the pseudonym Stephanie Barron, she is the author of eight bestselling Jane Austen mysteries. She lives in Colorado, where she is at work on her next novel of historical suspense.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter One

Later, they would remember that spring as one of the most glorious they'd ever known in Paris. The flowering of pleached fruit trees and the scent of lime blossom crushed underfoot, the chestnuts unfurling their leaves in ordered ranks along the Champs-Elysees, the women's silks rustling like wings as they hurried to dinner—all had a perilous sweetness, like absinthe. Sally King, who had lived in the city for nearly three years now and might be acknowledged as something of an expert, maintained that even when it rained Paris was ravishing. The streets shone in the sudden torrents regardless of grime or automobile petrol or the piss in the open urinals; they glistened with a brilliance that was consumptive and suicidal.

She was surging against the tide of people on the Pont Neuf that night, across the narrowest point of the little island that sat like a raft in the middle of the Seine, having already fought her way past the shuttered bookstalls of the Quai de la Tournelle. She did not move swiftly, because the French heels of her evening sandals caught in the cracks between the paving stones. It was dark, blackout dark, and she would have liked a taxi but there were none to be found. She could sense the panic in the hunched shoulders and too-rapid steps of the Parisians, some of whom turned despite their fear and stared at her openly: Sally King, tall and angular, all her beauty in the impossible length of her legs, the clarity of her frame beneath the candy-wrapper gown.

She had been living among them long enough now to perfect her schoolgirl French and she understood the spattering of rumor and fear. They've broken through the line. The Boches are through at Sedan. The army is in retreat—

The news from the Front had blown through the city like a boiling wind. A whisper on the northern outskirts. The report of a friend of a friend. The streets were blazing with half-truths and exaggeration under the deep blue dusk of the shaded lights, and most people were milling south. Sally pushed north, toward the Right Bank and the exquisite little flat fronting on the Louvre. Philip Stilwell's place.

He had left her waiting at a table with a splendid view of Notre-Dame, conspicuously alone at La Tour d'Argent, not her favorite restaurant in Paris but certainly the most expensive. It was unusual for a woman to arrive without an escort but Gaston Masson, La Tour's manager, was accustomed to the peculiarities of Americans. If the rest of his diners chose to speculate on the cost of Sally's dress, her probable immorality, her purpose in waiting nearly an hour for a man who never showed up—she was at least decorative, and hence valuable against the backdrop of the Seine. Her face, with its high cheekbones and too-wide smile, was said to be famous. She was freakishly tall. She carried a gas-mask case instead of a purse and wore last year's Schiaparelli--an economical gesture in time of war. Shocking pink silk, embroidered with acid green bugs.

"Perhaps M. Stilwell is delayed," Masson observed apologetically. "If the Germans have broken our line . . . if they have crossed the Meuse and even now are on the march through Belgium . . . a lawyer might have much to do . . ."

But not tonight, Sally thought as she picked her way across the ancient bridge. Tonight he was going to ask me to marry him.

The note had come at five o'clock, hand-delivered by one of Sullivan & Cromwell's messengers because she had no telephone in her flat in the Latin Quarter. Sally dearest I might be a little late for dinner this evening as I've an appointment with a member of the firm . . . Ask Gaston to seat you and order up a bottle of champagne. . . . A lawyer's wife, she'd thought, would have to adjust to such things. But Philip had never come; and rudeness was unlike him.

At the end of the bridge she hesitated. The darkened bulk of the Louvre loomed on her left. Without its usual blaze of light the city seemed forlorn and spectral, the people muttering through the streets like an army of the dead. Sally heard an air-raid siren shrill, and the high-pitched tinkle of breaking glass. A woman sobbed. Gooseflesh rose along her bare arms and she understood how solitary she was, how vulnerable. She ought to head for a bomb shelter, but nothing had fallen on Paris during the tedious eight months of phony war, so she squared her shoulders and walked toward Philip.

Another woman would have doubted herself. Assumed that he hadn't shown because he didn't love her. That simple thought never occurred to Sally. She had mapped Philip's soul quite thoroughly during the long months of the past winter, her job abruptly over, the whole question of her future hanging in the balance. She knew he'd been worried for weeks, and that it had something to do with S&C--with his work at the law firm of Sullivan & Cromwell.

They'd met the previous August, Philip new to Paris and losing his way on the Rue Cambon, searching for S&C's door and stumbling instead into the House of Chanel, which sat at number 31. Sally had been descending the famous staircase—Coco's preferred runway—to the admiration of the men and women seated expectantly below. It was Mademoiselle's fall collection, the last collection she would design for years, as it turned out. Sally had worn one of Coco's little black dresses, very chic and timeless in the usual manner; it was Chanel who'd made black fashionable when it had always been strictly for mourning. That August the color was disastrous, a presage of Poland's martyrdom, all diesel fumes and charred steel.

Philip watched the entire show from the doorway, and when approached by one of the vendeuses, stammered something about shopping for his mother. Sally'd agreed to have dinner with him, although she never really ate during the couture season. It was the beginning of an affair that had carried her headlong to this final night, the empty chair across the snowy linen, the curious gaze of the Paris streets. A meeting with a member of the firm, he'd said. And something had gone wrong.

Philip, she thought, fear knifing jaggedly through her. Philip.

She'd hung on all winter and spring in her apartment in the Latin Quarter, believing the news would change—hostilities would end—Hitler would go away. She rehearsed the truths Coco had taught her over the past three years, her inner voice less cultivated and more Western: Raise the waist in front and a girl looks taller. Lower the back, and you hide a drooping ass. Dip the hemline in the rear because it'll hitch up along the hips. Everything's in the shoulders. A woman should cross her arms when her measurements are taken: that way she allows for enough give.

He lived just off Rue de Rivoli where it met Rue St-Honore. An old limestone pile arranged around a courtyard, a tall double doorway flung open all day. Some dead aristocrat's hotel particulier, long since sliced into flats. Not a fashionable address, but Philip was too young and too foreign to know that. He wanted the heart of Paris: a view of the river from his salon, the cries of the knife-grinders beneath his window, church bells crashing into his bed at all hours of the night. Cracked boiserie and parquet that screamed underfoot. Mirrors so fogged they resembled pewter. Sally had lived in Paris longer but Philip loved the city better, loved the heartiness of her food and the guttural accents and the birdcages on the Ile Saint-Louis. Sunday mornings the two of them threw open the shutters and leaned on the windowsills, their shoulders suspended over the street, staring out at the world until their eyes ached.

She had four blocks still to walk when she saw the phalanx of cars from the prefecture de police. Philip's double-doored entry sprawled wide. Catching up her gas mask and silk dress, she began to run in the vicious sandals, straps cutting into her feet.

He was tied to the mahogany bedposts by his wrists and ankles, blood spattered the length of his nude body. She stood in the bedroom doorway swaying slightly, the police still unaware of her presence, and studied him: slack mouth, startled gray eyes, the latticework of ribs too embarrassingly white. The armpits monkeylike, the gourd of the hips and the knot of pubic hair at the groin, glistening with wetness. The erection still flagrant, even in death. Philip's penis, alert and red, something she'd touched once in a car. The whip forgotten on the rug beneath him. There was another man, also nude but a stranger to her, dangling from the chandelier. His toes were horribly callused, the joints blistered yellow.

Her mouth twisted and she must have gasped something in English—Philip's name, possibly—because one of the official French turned his head sharply and saw her, incongruous in her shocking pink gown. He scowled and crossed the room in three strides, blocking her view.

"Out, mademoiselle."

"But I know him!"

"I'm sorry, mademoiselle. You cannot be here. Antoine! Vite!"

She was grasped by the arm not ungently and led from the apartment, past the divan on which they'd had quick suppers, past the shutters they'd thrown open, a pair of highball glasses half-filled with drink. The wastebasket had overturned, and a few shards of glass were scattered on the threadbare Aubusson. She was dragged beyond the obscene figure dangling from the chandelier and into the hallway, where she began to shudder uncontrollably and the young man, Antoine—he wore a regular gendarme's uniform, not a detective's khaki raincoat—stood uncertainly clutching her elbow.

"Sally."

The quiet voice was one she knew. Max Shoop, who ran S&C's Paris office, in his elegant French clothes, his eyes remote and expressionless. They would have called Max, of course. She turned to him as a small child turns its face into its mother's apron, whimpering, her eyes scrunched closed.

"Sally," Max said again, and put an awkward hand on her bare shoulder. "I'm—sorry. I wish you hadn't seen that."

"Philip—"

"He's dead, Sally. He's dead."

"But how . . . ?" She pushed Shoop away, eyes open now and staring directly at him. "What in the world . . ."

"The police think it was a heart attack." He was uncomfortable with the words and all that had not been said: the meaning of the whip, the determined tumescence. Two men dead with a simultaneity that suggested climax. But Max Shoop was not the kind to admit discomfort: He maintained a perfect gravity, his face as expressionless as though he commented upon the weather.

"Who," she said with difficulty, "is hanging from the ceiling?"

Shoop's eyes slid away under their heavy lids. "I'm told he's from one of the clubs in Montmartre. Did you . . . know about Philip?"

"That he was . . . that he . . ." She stopped, uncertain of the words.

"My poor girl." Lips compressed, he led her away from the flat, toward the concierge's rooms one floor below. The good stiff shot of brandy that would be waiting there.

"It's not," she insisted clearly as he paused before the old woman's door, his hand raised to knock, "what you think, you know. It's not what you think."

Chapter Two

The revue at the Folies Bergeres didn't end until midnight, so Memphis never made it to the Alibi Club until one o'clock in the morning. Spatz knew exactly how the routine would go: The limousine and driver, the boy with the jaguar on its leash, Raoul hovering like a pimp in the background, his hands never far from his wife's ass. And Memphis herself: taller than a normal Parisienne, thinner and tauter, the muscles under the dark green velvet gown as coiled and sleek as the big cat beside her. She would pause in the curtained doorway as though searching the crowd—the Alibi Club was a true boute de nuit, a box of a room holding maybe ten tables—and the effect would be instantaneous. Every head would turn. Every man and woman would rise, and applaud her again for the simple fact of her existence, for the whiff of exotic sex she brought into the place, of jealousy unappeased.

Spatz had seen it all before, month after month of his enslavement to Memphis—which had endured somewhat longer, he reflected, than most of his amusements. He was content to sit alone, nursing a cigar, a plate of hideously overpriced oysters untouched before him. Hundreds of people lined up outside the Alibi Club, but only forty would be ushered through the entrance ropes—and only Spatz was given a table in a corner by himself. Spatz's careless patronage paid the bills. The fact that he was German and officially an enemy of everyone in the room was immaterial. The man's French was perfect; he drew no attention at all.

He was a broad-shouldered, elegantly clad animal of the highest pedigree: Hans Gunter von Dincklage, coddled son of a mixed parentage, child of Lower Saxony, blond and inhumanly charming. Spatz meant sparrow in German. The name did not immediately suit him until one understood his habit of darting from perch to perch, whim to whim. His official title during the past few years was diplomat, attached to the German embassy, but the embassy was closed now because of the state of war and Spatz was at loose ends. He had spent the winter in Switzerland but had drifted back to Paris as the guest of a cousin who lived in the sixteenth arrondissement. His wife he had divorced years ago on the grounds of incompatibility. His enemies pointed out that she had Jewish blood.

He had done nothing of real note in all his forty-five years except play polo well at Deauville.

A girl in fishnet tights was passing gin, but Spatz preferred Scotch. He had just palmed the heavy glass, feeling its weight as a comfort in the hand, when a man slid into the empty seat beside him.

"This is a private table."

"I don't care," the man snapped. "I've been hunting for you for hours, von Dincklage. You're ridiculously hard to find."

Spatz considered him. Fussy and small, with a toothbrush mustache and the sort of clothes that proclaimed the high-paid clerk; the sharp wet eyes of a blackmailer. He thought he could put a name to the man.

"You're Morris," he mused. "Emery Morris, am I right? You work for old Cromwell's outfit over near the Ritz."

"Sullivan and Cromwell," Morris corrected. "The New York law firm. I am a partner there."

"Call me tomorrow at home. I don't do business here."

Emery Morris glanced around him with a moue of distaste. "You'll have to make an exception. There is a matter of the gravest importance—"

From the Hardcover edition.

Later, they would remember that spring as one of the most glorious they'd ever known in Paris. The flowering of pleached fruit trees and the scent of lime blossom crushed underfoot, the chestnuts unfurling their leaves in ordered ranks along the Champs-Elysees, the women's silks rustling like wings as they hurried to dinner—all had a perilous sweetness, like absinthe. Sally King, who had lived in the city for nearly three years now and might be acknowledged as something of an expert, maintained that even when it rained Paris was ravishing. The streets shone in the sudden torrents regardless of grime or automobile petrol or the piss in the open urinals; they glistened with a brilliance that was consumptive and suicidal.

She was surging against the tide of people on the Pont Neuf that night, across the narrowest point of the little island that sat like a raft in the middle of the Seine, having already fought her way past the shuttered bookstalls of the Quai de la Tournelle. She did not move swiftly, because the French heels of her evening sandals caught in the cracks between the paving stones. It was dark, blackout dark, and she would have liked a taxi but there were none to be found. She could sense the panic in the hunched shoulders and too-rapid steps of the Parisians, some of whom turned despite their fear and stared at her openly: Sally King, tall and angular, all her beauty in the impossible length of her legs, the clarity of her frame beneath the candy-wrapper gown.

She had been living among them long enough now to perfect her schoolgirl French and she understood the spattering of rumor and fear. They've broken through the line. The Boches are through at Sedan. The army is in retreat—

The news from the Front had blown through the city like a boiling wind. A whisper on the northern outskirts. The report of a friend of a friend. The streets were blazing with half-truths and exaggeration under the deep blue dusk of the shaded lights, and most people were milling south. Sally pushed north, toward the Right Bank and the exquisite little flat fronting on the Louvre. Philip Stilwell's place.

He had left her waiting at a table with a splendid view of Notre-Dame, conspicuously alone at La Tour d'Argent, not her favorite restaurant in Paris but certainly the most expensive. It was unusual for a woman to arrive without an escort but Gaston Masson, La Tour's manager, was accustomed to the peculiarities of Americans. If the rest of his diners chose to speculate on the cost of Sally's dress, her probable immorality, her purpose in waiting nearly an hour for a man who never showed up—she was at least decorative, and hence valuable against the backdrop of the Seine. Her face, with its high cheekbones and too-wide smile, was said to be famous. She was freakishly tall. She carried a gas-mask case instead of a purse and wore last year's Schiaparelli--an economical gesture in time of war. Shocking pink silk, embroidered with acid green bugs.

"Perhaps M. Stilwell is delayed," Masson observed apologetically. "If the Germans have broken our line . . . if they have crossed the Meuse and even now are on the march through Belgium . . . a lawyer might have much to do . . ."

But not tonight, Sally thought as she picked her way across the ancient bridge. Tonight he was going to ask me to marry him.

The note had come at five o'clock, hand-delivered by one of Sullivan & Cromwell's messengers because she had no telephone in her flat in the Latin Quarter. Sally dearest I might be a little late for dinner this evening as I've an appointment with a member of the firm . . . Ask Gaston to seat you and order up a bottle of champagne. . . . A lawyer's wife, she'd thought, would have to adjust to such things. But Philip had never come; and rudeness was unlike him.

At the end of the bridge she hesitated. The darkened bulk of the Louvre loomed on her left. Without its usual blaze of light the city seemed forlorn and spectral, the people muttering through the streets like an army of the dead. Sally heard an air-raid siren shrill, and the high-pitched tinkle of breaking glass. A woman sobbed. Gooseflesh rose along her bare arms and she understood how solitary she was, how vulnerable. She ought to head for a bomb shelter, but nothing had fallen on Paris during the tedious eight months of phony war, so she squared her shoulders and walked toward Philip.

Another woman would have doubted herself. Assumed that he hadn't shown because he didn't love her. That simple thought never occurred to Sally. She had mapped Philip's soul quite thoroughly during the long months of the past winter, her job abruptly over, the whole question of her future hanging in the balance. She knew he'd been worried for weeks, and that it had something to do with S&C--with his work at the law firm of Sullivan & Cromwell.

They'd met the previous August, Philip new to Paris and losing his way on the Rue Cambon, searching for S&C's door and stumbling instead into the House of Chanel, which sat at number 31. Sally had been descending the famous staircase—Coco's preferred runway—to the admiration of the men and women seated expectantly below. It was Mademoiselle's fall collection, the last collection she would design for years, as it turned out. Sally had worn one of Coco's little black dresses, very chic and timeless in the usual manner; it was Chanel who'd made black fashionable when it had always been strictly for mourning. That August the color was disastrous, a presage of Poland's martyrdom, all diesel fumes and charred steel.

Philip watched the entire show from the doorway, and when approached by one of the vendeuses, stammered something about shopping for his mother. Sally'd agreed to have dinner with him, although she never really ate during the couture season. It was the beginning of an affair that had carried her headlong to this final night, the empty chair across the snowy linen, the curious gaze of the Paris streets. A meeting with a member of the firm, he'd said. And something had gone wrong.

Philip, she thought, fear knifing jaggedly through her. Philip.

She'd hung on all winter and spring in her apartment in the Latin Quarter, believing the news would change—hostilities would end—Hitler would go away. She rehearsed the truths Coco had taught her over the past three years, her inner voice less cultivated and more Western: Raise the waist in front and a girl looks taller. Lower the back, and you hide a drooping ass. Dip the hemline in the rear because it'll hitch up along the hips. Everything's in the shoulders. A woman should cross her arms when her measurements are taken: that way she allows for enough give.

He lived just off Rue de Rivoli where it met Rue St-Honore. An old limestone pile arranged around a courtyard, a tall double doorway flung open all day. Some dead aristocrat's hotel particulier, long since sliced into flats. Not a fashionable address, but Philip was too young and too foreign to know that. He wanted the heart of Paris: a view of the river from his salon, the cries of the knife-grinders beneath his window, church bells crashing into his bed at all hours of the night. Cracked boiserie and parquet that screamed underfoot. Mirrors so fogged they resembled pewter. Sally had lived in Paris longer but Philip loved the city better, loved the heartiness of her food and the guttural accents and the birdcages on the Ile Saint-Louis. Sunday mornings the two of them threw open the shutters and leaned on the windowsills, their shoulders suspended over the street, staring out at the world until their eyes ached.

She had four blocks still to walk when she saw the phalanx of cars from the prefecture de police. Philip's double-doored entry sprawled wide. Catching up her gas mask and silk dress, she began to run in the vicious sandals, straps cutting into her feet.

He was tied to the mahogany bedposts by his wrists and ankles, blood spattered the length of his nude body. She stood in the bedroom doorway swaying slightly, the police still unaware of her presence, and studied him: slack mouth, startled gray eyes, the latticework of ribs too embarrassingly white. The armpits monkeylike, the gourd of the hips and the knot of pubic hair at the groin, glistening with wetness. The erection still flagrant, even in death. Philip's penis, alert and red, something she'd touched once in a car. The whip forgotten on the rug beneath him. There was another man, also nude but a stranger to her, dangling from the chandelier. His toes were horribly callused, the joints blistered yellow.

Her mouth twisted and she must have gasped something in English—Philip's name, possibly—because one of the official French turned his head sharply and saw her, incongruous in her shocking pink gown. He scowled and crossed the room in three strides, blocking her view.

"Out, mademoiselle."

"But I know him!"

"I'm sorry, mademoiselle. You cannot be here. Antoine! Vite!"

She was grasped by the arm not ungently and led from the apartment, past the divan on which they'd had quick suppers, past the shutters they'd thrown open, a pair of highball glasses half-filled with drink. The wastebasket had overturned, and a few shards of glass were scattered on the threadbare Aubusson. She was dragged beyond the obscene figure dangling from the chandelier and into the hallway, where she began to shudder uncontrollably and the young man, Antoine—he wore a regular gendarme's uniform, not a detective's khaki raincoat—stood uncertainly clutching her elbow.

"Sally."

The quiet voice was one she knew. Max Shoop, who ran S&C's Paris office, in his elegant French clothes, his eyes remote and expressionless. They would have called Max, of course. She turned to him as a small child turns its face into its mother's apron, whimpering, her eyes scrunched closed.

"Sally," Max said again, and put an awkward hand on her bare shoulder. "I'm—sorry. I wish you hadn't seen that."

"Philip—"

"He's dead, Sally. He's dead."

"But how . . . ?" She pushed Shoop away, eyes open now and staring directly at him. "What in the world . . ."

"The police think it was a heart attack." He was uncomfortable with the words and all that had not been said: the meaning of the whip, the determined tumescence. Two men dead with a simultaneity that suggested climax. But Max Shoop was not the kind to admit discomfort: He maintained a perfect gravity, his face as expressionless as though he commented upon the weather.

"Who," she said with difficulty, "is hanging from the ceiling?"

Shoop's eyes slid away under their heavy lids. "I'm told he's from one of the clubs in Montmartre. Did you . . . know about Philip?"

"That he was . . . that he . . ." She stopped, uncertain of the words.

"My poor girl." Lips compressed, he led her away from the flat, toward the concierge's rooms one floor below. The good stiff shot of brandy that would be waiting there.

"It's not," she insisted clearly as he paused before the old woman's door, his hand raised to knock, "what you think, you know. It's not what you think."

Chapter Two

The revue at the Folies Bergeres didn't end until midnight, so Memphis never made it to the Alibi Club until one o'clock in the morning. Spatz knew exactly how the routine would go: The limousine and driver, the boy with the jaguar on its leash, Raoul hovering like a pimp in the background, his hands never far from his wife's ass. And Memphis herself: taller than a normal Parisienne, thinner and tauter, the muscles under the dark green velvet gown as coiled and sleek as the big cat beside her. She would pause in the curtained doorway as though searching the crowd—the Alibi Club was a true boute de nuit, a box of a room holding maybe ten tables—and the effect would be instantaneous. Every head would turn. Every man and woman would rise, and applaud her again for the simple fact of her existence, for the whiff of exotic sex she brought into the place, of jealousy unappeased.

Spatz had seen it all before, month after month of his enslavement to Memphis—which had endured somewhat longer, he reflected, than most of his amusements. He was content to sit alone, nursing a cigar, a plate of hideously overpriced oysters untouched before him. Hundreds of people lined up outside the Alibi Club, but only forty would be ushered through the entrance ropes—and only Spatz was given a table in a corner by himself. Spatz's careless patronage paid the bills. The fact that he was German and officially an enemy of everyone in the room was immaterial. The man's French was perfect; he drew no attention at all.

He was a broad-shouldered, elegantly clad animal of the highest pedigree: Hans Gunter von Dincklage, coddled son of a mixed parentage, child of Lower Saxony, blond and inhumanly charming. Spatz meant sparrow in German. The name did not immediately suit him until one understood his habit of darting from perch to perch, whim to whim. His official title during the past few years was diplomat, attached to the German embassy, but the embassy was closed now because of the state of war and Spatz was at loose ends. He had spent the winter in Switzerland but had drifted back to Paris as the guest of a cousin who lived in the sixteenth arrondissement. His wife he had divorced years ago on the grounds of incompatibility. His enemies pointed out that she had Jewish blood.

He had done nothing of real note in all his forty-five years except play polo well at Deauville.

A girl in fishnet tights was passing gin, but Spatz preferred Scotch. He had just palmed the heavy glass, feeling its weight as a comfort in the hand, when a man slid into the empty seat beside him.

"This is a private table."

"I don't care," the man snapped. "I've been hunting for you for hours, von Dincklage. You're ridiculously hard to find."

Spatz considered him. Fussy and small, with a toothbrush mustache and the sort of clothes that proclaimed the high-paid clerk; the sharp wet eyes of a blackmailer. He thought he could put a name to the man.

"You're Morris," he mused. "Emery Morris, am I right? You work for old Cromwell's outfit over near the Ritz."

"Sullivan and Cromwell," Morris corrected. "The New York law firm. I am a partner there."

"Call me tomorrow at home. I don't do business here."

Emery Morris glanced around him with a moue of distaste. "You'll have to make an exception. There is a matter of the gravest importance—"

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“What a movie The Alibi Club would make.”—Chicago Tribune

"Imagine the impeccable period details of Alan Furst's novels about Paris during WWII mixed with a cast straight out of Casablanca and you begin to get some idea of the pleasures on tap in Mathew's new thriller."—Publishers Weekly, starred review

"A unique portrait of life on the edge of horror... [with] a remarkable cast of characters."—San Francisco Chronicle

From the Hardcover edition.

"Imagine the impeccable period details of Alan Furst's novels about Paris during WWII mixed with a cast straight out of Casablanca and you begin to get some idea of the pleasures on tap in Mathew's new thriller."—Publishers Weekly, starred review

"A unique portrait of life on the edge of horror... [with] a remarkable cast of characters."—San Francisco Chronicle

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

Set against the backdrop of a stunning, little-known episode of early World War I, this suspenseful novel follows four women, thrown together by chance, who make a perilous attempt to smuggle a brilliant atomic fusion scientist and his lethal secrets away from Nazi control.