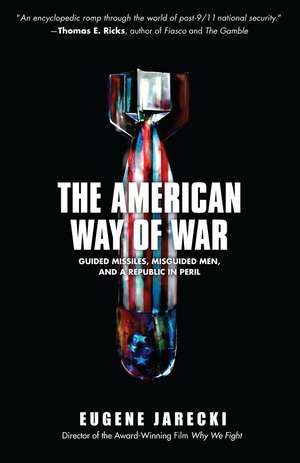

The American Way of War: Guided Missiles, Misguided Men, and a Republic in Peril

Autor Eugene Jareckien Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2009

In his now legendary 1961 farewell address, President Dwight D. Eisenhower warned of "the disastrous rise of misplaced power" that could result from the increasing influence of what he called the "military industrial complex." Nearly two centuries earlier, another general turned president, George Washington, had warned that "overgrown military establishments" were antithetical to republican liberties. Today, with an exploding defense budget, millions of Americans employed in the defense sector, and more than eight hundred U.S. military bases in 130 countries, the worst fears of Washington and Eisenhower have come to pass.

Surveying a scorched landscape of America's military adventures and misadventures, Jarecki's groundbreaking account includes interviews with a who's who of leading figures in the Bush administration, Congress, the military, academia, and the defense industry, including Republican presidential nominee John McCain, Colin Powell's former chief of staff Colonel Lawrence Wilkerson, and longtime Pentagon reformer Franklin "Chuck" Spinney. Their insights expose the deepest roots of American war making, revealing how the "Arsenal of Democracy" that crucially secured American victory in WWII also unleashed the tangled web of corruption America now faces. From the republic's earliest episodes of war to the use of the atom bomb against Japan to the passage of the 1947 National Security Act to the Cold War's creation of an elaborate system of military-industrial-congressional collusion, American democracy has drifted perilously from the intent of its founders. As Jarecki powerfully argues, only concerted action by the American people can, and must, compel the nation back on course.

The American Way of War is a deeply thoughtprovoking study of how America reached a historic crossroads and of how recent excesses of militarism and executive power may provide an opening for the redirection of national priorities.

Preț: 119.61 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 179

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.89€ • 23.90$ • 18.94£

22.89€ • 23.90$ • 18.94£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781416544579

ISBN-10: 1416544577

Pagini: 324

Dimensiuni: 137 x 211 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Free Press

ISBN-10: 1416544577

Pagini: 324

Dimensiuni: 137 x 211 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Free Press

Extras

Introduction: Mission Creep

What are we fighting for? Why do we bury our sons and brothers in lonely graves far from home? For bigger and better business? You know the answer. We're fighting for liberty -- the most expensive luxury known to man. These rights, these privileges, these traditions are precious enough to fight for, precious enough to die for.Lieutenant General Brehon SomervellFort Belvoir, VirginiaMarch 9, 1944

First, a confession. This book is not written by a policy scholar, nor a soldier, nor an insider to the workings of America's military establishment. I am first and foremost a filmmaker, whose 2006 documentary Why We Fight sought to make sense of America's seemingly inexorable path to the tragic quagmire in Iraq. Though I lost friends in the attacks of 9/11 and thus understood the public outrage they produced, I was distressed to see a national tragedy converted by the White House into the pretext for a preemptive war. Still, following the attacks, and prior to being drowned out by war drums from the White House, there was a period of soul-searching among many of the people I knew.

This spirit was briefly magnified by the mainstream media into the inflammatory query, "Why do they hate us?" -- a question that exaggerated the issue, equating any effort simply to understand the roots of the crisis with blaming America for the attacks committed against it. "Why do they hate us?" also did more to forge a gulf between "them" and "us" than to address the deeper questions on people's minds: questions about the state of the world and America's role in it, such as "How did we get to this point?", and "where are we going?"

Before long, as war became inevitable, attention to these questions faded, and public discourse turned predictably partisan. As pro- and antiwar camps hardened, I sought to examine the forces that had so quickly plunged the nation into conflict on several fronts -- from the unlimited battle space of the so-called war on terror to the front lines of Iraq. During the earliest days of World War II, the legendary Hollywood director Frank Capra had made his Why We Fight films for the U.S. military, examining America's reasons for entering that war. At a new time of war, Capra's driving questions take on renewed resonance: "Why are we Americans on the march? What turned our resources, our machines, our whole nation into one vast arsenal, producing more and more weapons of war instead of the old materials of peace?"

A half century since Capra posed these questions, the answers seemed less clear than ever. In order first to research my film and then, upon its release, to show it to audiences, I traveled to the farthest reaches of America's military and civilian landscapes, to military bases and defense plants, to small towns and large towns from the Beltway to the heartland. Among the many things I learned on my travels is that neither supporters nor critics of the Bush administration seemed to understand how its warmaking and sweeping assertions of executive power fit into the long history of the American Republic. Instead, for the most part, critics and supporters were locked in a shallower debate,with one side citing 9/11 as grounds for the administration's radical doctrine of preemption, and the other side vilifying George W. Bush and his team as an overwhelming threat to all that is great and good about America. Lost in this shouting match was any real understanding of what Bush and his wars represent in the larger story of what a thoughtful Air Force colonel described to me as "the American way of war."

Along my journey, I met the characters who appear in these pages. Whether civilian or military, each has been touched by the Iraq War and past American wars in one way or another. And each has a story to tell that sheds light on war's larger political, economic, and spiritual implications for American life. While this book is principally a survey of the evolution of the American system from its birth in a war of revolution to its contemporary reality as the world's sole superpower, it is ultimately a human system -- composed of humans and guided by the ideas, aspirations, and contradictions of humans. As such, the characters in this book lend humanity to its analysis, reminding us that the faceless forces examined here have been set in motion by humans and can thus be redirected by them.

Many of the people portrayed in this book are themselves selfacknowledged works-in-progress. What I came to admire about many of them is their courage in having traveled great personal distance in their understanding of the system in which they have operated, and in many cases continue to operate. Their stories not only illuminate their particular areas of expertise but, by demonstrating their personal capacity to change and grow, remind us of that prospect for ourselves, and for the system of which we are all a part.

As America now hopes to leave the traumatic first years of the twentyfirst century behind and move into a period of loftier ambitions, the nation remains embroiled in a tragic conflict with no clear objective or foreseeable exit. Given all that has come to light about the errors and misdeeds of the Bush years, there is an understandable temptation to dwell on how George W. Bush and those around him could have so misguided the nation, destabilized the world, and compromised America's position in it. Yet, while accountability for these actions is vital, it must be accompanied by rigorous efforts to understand the historical forces that brought America to a place from which Bush's radicalization of policy was possible. Without such vigilance by what Eisenhower called "an alert and knowledgeable citizenry," the system is prone to repeat and, worse, to build on the regrettable patterns of recent years.

From her birth, America was shaped by a contradiction of impulses among the founders. On the one hand, given their difficult experience as colonists under British rule, these men sought to design a republic that would avoid the errors of past major powers. On the other hand, they saw the nation's vast potential and recognized that, no matter how well intended, its government could one day face the dilemmas encountered by its imperialist precursors. The Roman Republic had been overwhelmed by Caesar's imperial ambitions, and the framers recognized that the American system would need to keep the power of its leaders in check. "If men were angels," James Madison noted, "no government would be necessary."

From this insight followed the brilliant concept of the separation of powers, with checks and balances between them; and among these, none was more important to the framers than the constraints placed on the power of any individual to take the country to war. They thus intentionally entangled the authority to declare and prosecute war in a complex web of interlocking responsibilities between the branches.

Looking back from a contemporary vantage point -- at a time of great friction among the branches over the separation of powers -- it's remarkable both how prescient the framers were and yet how much, despite their efforts, events have come to fulfill their worst fears.

In his 1796 Farewell Address, George Washington provided several pieces of indispensable guidance for the generations that would follow. Warning against "permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world," he declared that "overgrown military establishments" were antithetical to republican liberties. Washington's idea was simple. If America stayed clear of the infighting that had historically gone on between European nations, it would much less often face the pressure to go to war and incur its attendant political, economic, and spiritual costs.

Almost two centuries later, on January 17, 1961, another generalturned-president would echo Washington in his own Farewell Address. "We have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions," declared Dwight D. Eisenhower, warning famously that America must "guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence...by the military-industrial complex." Eisenhower's warning against the "MIC," as it has come to be known, was a milestone in American history. From his firsthand experience, Eisenhower felt compelled to warn the nation that in the wake of World War II and amid its efforts to fight the Cold War, military, industrial, and political interests were forming an "unholy alliance" that was distorting America's national priorities.

As the chapters of this book explore, between Washington's time and Eisenhower's, and in turn between Eisenhower's and today, with each of the wars America has fought, she has drifted ever further from the framers' desired balance between a certain measure of isolationism and the necessity to defend the country. With each war, too, the separation of powers has suffered, with the executive branch coming to far outweigh the others in influence, agency, and power.

Examining the history of how this came to pass is in no way intended to minimize the errors, moral compromises, and outright offenses perpetrated by George W. Bush and his administration. Yet it does offer a deeper explanation of how such a radical chapter in the history of American policy was made possible by what preceded it. Only by getting at these roots of the American way of war can we begin to develop a realistic prescription for the nation's repair.

At the heart of this analysis is a military concept known as "mission creep." This term could have been used to describe any number of American wars from Korea to Vietnam to Iraq. But it first appeared in 1993 in articles on the UN peacekeeping mission in Somalia. Since then, it has swept into the parlance of Pentagon planners and, like so many terms that start in the military, spread into other fields. It means simply "the gradual process by which a campaign or mission's objectives change over time, especially with undesirable consequences."1

Not since John F. Kennedy has the relationship between a sitting president and his father been as talked about as that between George W. Bush and George H. W. Like Kennedy, George Junior grew up in the shadow of a powerful patriarch to whom his political ascent was widely attributed. But unlike Kennedy, George Junior's presidency was from the start undermined by rumors of significant ideological difference, distance, and disapproval from his father. George Senior has at times tried to dispel this impression, yet his body language and public statements by key members of his inner circle betray otherwise.

Nowhere does the gulf between father and son reveal itself more vividly than in the first Bush's 1992 memoir, entitled A World Transformed. Explaining his decision not to pursue the overthrow of Saddam Hussein after the 1991 Gulf War, the forty-first president could not have imagined that his words might one day challenge his son's decision to do just that:

We would have been forced to occupy Baghdad and, in effect, rule Iraq. The coalition would instantly have collapsed, the Arabs deserting it in anger and other allies pulling out as well. Under the circumstances, there was no viable "exit strategy" we could see....Released during the Clinton years, Bush's memoir was generally perceived as a faint echo of a bygone time. But as George Junior's war in Iraq began slipping into a quagmire he hadn't anticipated, his father's words were brought back by critics to haunt him.

Had we gone the invasion route, the U.S. could conceivably still be an occupying power in a bitterly hostile land. It would have been a dramatically different -- and perhaps barren -- outcome.It's almost painful to read how clearly the elder Bush can foresee the fate that awaits his son. But beyond the battlefield, Bush Senior also predicted the larger danger of drifting policy rationales:

Trying to eliminate Saddam, extending the ground war into an occupation of Iraq would have violated our guideline about not changing objectives in midstream, engaging in "mission creep," and would have incurred incalculable human and political costs.2As George W. Bush's rational for war in Iraq shifted -- from a link between Saddam and 9/11, to Iraq's possession and development of weapons of mass destruction, to the goal of liberating the Iraqi people, to suppressing an insurgency, and now to scrambling to contain the fallout of a tragically misguided conflict -- the Iraq War has been a case study in mission creep.

Still, this book is not about the drifting mission of George Junior's misadventure in Iraq. Rather, it sees this drift as a symptom -- and a predictable one -- of a broader mission creep that has afflicted the country since its very founding. Though the Bush administration has, without question, asserted unprecedented executive powers and done farreaching damage to the republic, the foreign and domestic policies of George W. Bush were not born overnight. And just as American soldiers now retread paths well worn during past engagements in the Iraqi desert and elsewhere, so too Bush's trespasses at home and abroad have deep roots in the country's history.

Copyright © 2008 by Eugene Jarecki

Notă biografică

Eugene Jarecki