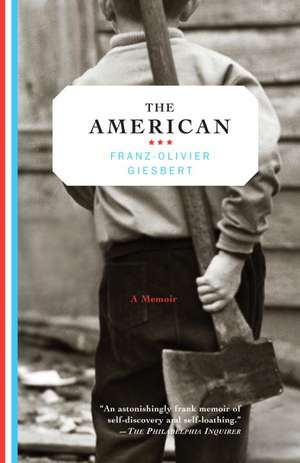

The American

Autor Franz-Olivier Giesberten Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2007

Preț: 79.45 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 119

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.20€ • 15.92$ • 12.58£

15.20€ • 15.92$ • 12.58£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400095858

ISBN-10: 1400095859

Pagini: 160

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 11 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 1400095859

Pagini: 160

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 11 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Notă biografică

Franz-Olivier Giesbert is a prominent French intellectual, though he was born in Wilmington, Delaware and spent the first three years of his life in America. He is a novelist, biographer, television host and newspaper editor. He has worked at Le Nouvelle Observateur as its Washington correspondent and served as Editor-in-Chief of Le Figaro.

Extras

I’ve spent my life trying to get myself forgiven. As far back as I can remember, it seems as though I’ve never been up to it, on any level. It’s a feeling that gives me a knot in my stomach, often, when I have the misfortune of find- ing myself alone with myself. In bed, for example, when I can’t sleep.

I have to avoid myself. That’s vital. I’ve tried, for several decades now, with a certain success. Once in a while I linger in front of a mirror to check out my blank insomniac face or to find a pimple or a new age spot, but I’ve always stayed away from introspection. I don’t think I could survive psychoanalysis.

This is therefore not an analysis sublimated by writing, as certain novels have tended to be. It is my story, a story I have been careful never to tell myself, for fear I wouldn’t be able to stand it. But I would like today to unroll its thread, now that I have arrived at the sunset of my life, and pay my respects, before I join them, to those who made me.

To my father, most of all. To my father whom I was so ashamed of and with whom I think I never talked. Except maybe to ask him to pass the salt or something at dinner, and even that, I’m not sure of. In the last years of his life, each time he hung around me waiting to start a conversation, I changed rooms. I kept putting off the reconciliation that couldn’t fail to be produced if death hadn’t stolen him from my disaffection.

I had an excuse. My father robbed me of my childhood. It’s because of him that I have always seen the world through adult eyes. Even at the age of five or six, I was already without illusions. As well as I can recollect, I never believed in Santa Claus. It’s hard to believe in Santa Claus in a house where the wife is beaten to a pulp several times a week.

I can’t say when my father began beating my mother, but I knew why. Even when he didn’t find a pretext, he had a reason. He resented the whole world, and my mother most of all, for ruining his life. Papa was an artist, a real one, it seems, and he blamed Mother for preventing him from being the great artist he could feel welling up inside him, by ceaselessly making him children. He didn’t like children. They condemned him to bourgeois mediocrity, which he spat upon every single day. Because of his children he had to renounce his palette and easel in order to spend hours boiling up “commercial art,” an expression that, in his mouth, was always an insult and designated prospectuses, catalogs, or posters.

Mother gave him five children. In a voice too tired not to show its fatigue, he called us “mouths to feed,” so it was impossible to be unaware of the weight we represented on his shoulders, which were nevertheless broad and powerful. He simply beat us cold. He beat us, too, especially me, because I stood up to him more than I could make good on, with the air of a village cock, in order to avenge Mother.

Snapshots of that time show me standing a bit apart from the family, head lowered, seemingly closed off. I wasn’t unhappy, though. My head was already filled with a Good Lord of grass, love, dreams, and beasts, not to speak of the Lord and the Holy Virgin who, from Heaven, watched over me, I believed, like milk on the stove. It was just that I was ravaged by hatred. Hate for my father, whom I imagined myself killing sooner or later.

Papa slept with a knife under his pillow. It was a habit he acquired in the army, after the Normandy landing, when his nights were filled with Germans crawling around to kill Yankees, knives between their teeth.

I imitated him. For a long time, I slept with a pocket knife under my pillow, so as to be able to disembowel my father if he ever made trouble for me at night. Although I thought a lot about this project, I don’t think I would have been able to kill him in cold blood, looking him straight in the eyes. I was too afraid of him.

Papa had a propensity for great anger and great violence. Not with everyone, however. In town, he wouldn’t have hurt a fly. I am even sure he let people step on his toes in the bars of Elbeuf, where he often hung out after work. He was the way immigrants often are. He didn’t want to go back to his country. He was afraid of being noticed, having his work permit confiscated, and being sent back to the United States of America, his mother country, which he hated as much as I venerated it.

At home, on the other hand, anything would set him off, particularly when he came back drunk. He wasn’t a happy drunk; that was the least anyone could say of him. The disappearance of a screwdriver could take on seismic proportions; the walls trembled until he found it where he had left it the day before. Same thing if he discovered that some tool—a trowel or a scythe—had been left out in the rain to rust: a family specialty. At the dinner table, he blew up over nothing, an ambiguous imitation or a furtive smile, and blows rained down like shells at the battle of Gravelotte. We often had to evacuate the wounded, after the meal.

That’s why I had a horror of dinners at home. Nights too, since Papa often waited until the lights were out to slug Mother. Sometimes he bellowed out expletives while he hit her. Other times, he just yelled. There were the sounds of a struggle, furniture moving, doors slamming, but I rarely heard my mother complain while she was being pelted by his fists. Sometimes, muffled screams came out of her, which still pierce my ears, fifty years later. But most of the time, in order not to wake the children, she kept her cries to herself, in the pit of her stomach, where they fed a cancer that was biding its time.

On those nights I stayed in bed, my heart beating, my blood frozen, trembling like a leaf. I was dying. I think one always dies a little when one hears one’s mother beaten. I spent a part of my childhood dying, but only part. In the other part, of course, I grew stronger.

2

I’m not sure how old I was, maybe four or five, maybe more, but I remember that it was raining hard and my brothers were not yet born. It was a summer night, in Italy, on the side of Venice where my father liked to spend vacations. We found ourselves, Papa, Mother, my two sisters, and I, in the family car, a Renault that was built like a big bicycle. My mother was reading the road map with a flashlight in her hand, in order to indicate our route to my father, who was in a bad mood because of the bad weather.

“Where are you taking us?” bellowed my father suddenly. “We just passed by here!”

“I don’t think so.”

“You’re making us go around in circles. Don’t you recognize this intersection?”

He stopped the car on the shoulder and grabbed the map and the flashlight from my mother. He concentrated a long time while sighing noisily, because he only did things halfway, before muttering, “You’re wrong again. You don’t even know how to read a map.”

“You’re the one who doesn’t know how to follow my instructions.”

For that act of insolence, Mother got a first blow that knocked her against the car window. Papa didn’t know how to control his strength. He always hit harder than he intended to. His slaps were like punches.

My mother, despite the schoolgirl masochism that was eating her up and that I’ll come back to, sometimes had a good comeback. She muttered calmly, which made her case worse, “If you think that is how you’ll find your way, old man—”

She received a new blow, even stronger than the first, to judge by the sound she made: a dull sound, like the sound red meat makes when the butcher throws it on his worktable before cutting it up. Nevertheless, she didn’t consider the discussion over.

“You beast!” she cried.

Third blow, same dull sound. But this time Mother gathered herself up. There were limits to her masochism. She threw herself against Papa’s chest, screaming and drumming against him like an angry child. I always felt very afraid when my mother resisted like that. She wasn’t up to it.

If I remember correctly—and I think I do, at least when it comes to this event—that night my mother did not, as she often had in the past, reproach my father for beating her in front of the children. In fact I’m sure the thought never entered her head. That was when we were beginning to get used to Papa’s rages.

His muscles reacted first. Especially the hand muscles, to be precise. The head followed. One could never look for my father as cause of an action. He no longer answered for anything. For a trifle, he could have killed my mother without intending to, just by punching her wrong. That was why it was my duty as the eldest to kill him before he committed the irreparable.

I didn’t yet have the bulk to stand up to him, but I bided my time, to be sure to accomplish my design. With a knife, with an ax, with a mallet; I hadn’t yet chosen the instrument. However it happened, I at least knew that my father would suffer a thousand deaths, and maybe more.

That’s what I said to myself, that night, on the backseat of the Renault, while I pouted and Papa riddled Mother with punches. He hit her while breathing heavily, and heaved a logger’s groan each time he struck a blow. He applied himself to the task, for he didn’t take anything lightly, especially vacations.

Mother was crying, all wrapped up in her own body, protecting her head with her arms. She was crying without ostentation under the volley of blows, waiting for it to be over. Years later, on reading Ecclesiastes, I understood my mother’s philosophy. For her, there was a time for everything: a time to tear and a time to mend, a time to love and a time to hate. For nothing under the sun can last, neither happiness nor unhappiness. I knew then that she had been much stronger than he was.

It goes without saying that we were crying too, my sisters and I. My father, who ordinarily couldn’t stand the sound of children crying, let us wail our eyes out when he beat Mother. At the time, I thought he was too busy correcting Mother to have time to tell us to shut up. Now, after considering it some more, I think it was his way of telling us we were right.

Papa had extinguished the flashlight, no doubt so as not to use up the battery, during this session with Mother. I could see nothing in the darkness, but I remember that at a given moment my father took my mother’s nose and gave it a twist, unless he crushed it, but if so, the damage would have been visible the next day, and it wasn’t.

“You beast!” cried my mother again, using her favorite insult. “You’ve broken my nose!”

“That’ll teach you.”

“You can just manage on your own now.”

That was the one thing that should never be said. But against all expectations, Papa decided to stop his attack. He acted like someone who hadn’t heard anything and continued on his way without saying a word.

It was still raining when we reached our destination, a second-class campground like all those where we spent our vacations, in the midst of the smell of soap and dirty water. Papa thought it prudent not to put up the tent on its stakes, so all five of us slept, all tangled up, in the family car, in the silence that comes after a storm.

The following day, Papa uncorked some Lambrusco and some Asti Spumante. He was ashamed. My father was always submerged in shame, afterward. He could look at no one and spent hours without unclenching his teeth. That suited us perfectly. No one spoke to him, either. As for me, I had a good reason to keep quiet. I was too busy replaying the film of the fight and planning my revenge. It was the following night, I think, that I wet the bed for the last time.

3

The air was very heavy in our house along the Seine, in Saint-Aubin-lès-Elbeuf. Over everything there reigned a certain violence that crushed you, at least when my father was there. That was surely the reason I developed the bad habit of breathing economically, in little gasps, like a person with asthma.

To this day it sometimes happens that I forget to breathe. My turn goes by. Thus I live between two apneas, more or less. If it were not for the bright lights on the sides of my eyes and the sensation of suffocating—which, from time to time, recall me to order—I think I would have died of asphyxiation long ago.

Often, Mother sent us to her parents’ house, just over a mile away from ours, to unwind a bit. They lived in an enormous apartment over the Allain Press, named after my grandfather, an austere boss, his thin hair slicked back, his eyeglasses stern, his mustache square, who was constantly working and, in order to apologize for that, showered his descendants with gifts.

Most of the time, generosity is just disguised indifference, a way to buy tranquillity. That could not have been true of Papi, as we called him. He had real goodness in his look and smile, and a kind of sweet and attentive irony escaped him, for he sought above all to give the impression, even within the family, that he was uncompromisingly stiff and rigid.

I adored Papi. There was something pathetic about his desire for his twenty grandchildren, with their mothers, to spend at least part of their summer vacations together in a big house that he rented for them in Normandy or Brittany. Or about the interminable dinner parties he organized, made up of family friends and distant cousins. He might have seemed to be seeking a kind of posterity for himself. But he was too proud to have room to be vain, too.

He doubtless foresaw that someday a great seismic event, his death or something else, would devastate everything he had patiently built up over the years: the press, the family, the dynasty. He was too imbued with the ancients he was always reading—Plato or Plutarch—to nourish the illusion that one could leave any trace of oneself on this earth. He didn’t believe in God any more than in the future. His children discovered this rather starkly when they opened his will and read that he was a Christian but not a believer, he wanted to be buried in secret at sun- set, and he wanted to go directly from the house to the cemetery.

Up till then, Papi had always acted like a model parishioner, a great consumer of hosts. That was how I learned that one knows very little about other people before their deaths, even one’s own grandfather. Once they have mounted the stage boards of life, they continue, up until the last speech, to play a character in whom they have ceased to believe. Not wanting to rock the boat, Papi let those who were familiar with his will be his judges and either carry out or not carry out his wishes. They, of course, covered what he said with a handkerchief.

I have spoken of Papi’s goodness. But however sociable he was, he couldn’t stand to have anyone put his authority in question. Not the typographical union leaders, whom he fired without hesitating. Not my father, who worked for his press in the “department of design,” as we called it. I don’t think Papi took advantage of his position to humiliate his son-in-law, but Papa had contestation in his blood, fueled by his passion for American writers like Upton Sinclair, John Dos Passos, and John Steinbeck.

Papa was not a Marxist. He felt a merciless hatred, in fact, for Communists and their fellow travelers, whom he accused of sowing death wherever they went. I heard him say once that he would fear for his life if they ever came to power in France thanks to an invasion by the Soviet Union—a hypothesis, by the way, that he imagined seriously. But at the same time, he loathed bosses most of all, and all those who, like my grandfather, believed they had come—it was one of his favorite expressions—directly out of “Jupiter’s thigh.”

My grandfather certainly had no idea how much Papa hated him, because, as was his wont, Papa said bad things about him only behind his back—that is, in front of us, at home. Papa accused him of everything—greed, stinginess, tyranny, meanness—and, which didn’t make things any easier, he was also jealous of him. He couldn’t abide their conspiratorial tones and low voices when Papi and Mother exchanged books, magazines, smiles, or secrets.

That is no doubt the reason he got along so well with my maternal grandmother. They both shared, I think, the same hatred of Papi. The same passion for music, too. Winner of first place at the Paris conservatory, Mamie made me cry when she played, with ineffable skill, Bach or Dupré, her great friend, on the organs of the churches of Elbeuf.

But she did everything to kill the artist in her. Except when she was in front of an organ, once or twice a month, not much remained of the musician Papi thought he’d married, inflamed as he was from the moment he laid eyes on her, the great Romantic, seeing the sad-eyed girl with the prominent eyeballs whose blind father was a piano tuner. He asked her to respond to his marriage proposal in music: If the answer was yes, she was to play a Bach fugue at Sunday mass. She played the fugue.

As the years passed, Mamie drowned in masochism, that family curse. Once funny, lively, and cultivated, her heart in her hand, a pelican’s heart, she was subject to sudden absurd outbursts, over a laundry mark or insipid friends. She repeated the same expressions all day long; for example, about her grandchildren: “It’s scary how cute he is.” She confined the perimeter of her conversation to the babies, the clothes, the vacuum cleaners, and the cleaning products, while keeping, nevertheless, down to her last drop of life, each time she took her place at a keyboard, the same magic at the tips of her fingers. Papi took a mistress in Paris and loved her passionately. He fled regularly to Italy, where he always spent vacations with her, around Lake Como. He sent us postcards saying “love and kisses.”

Mamie often confronted him with scenes of jealousy. I even saw her slap my grandfather around one Sunday night when he tiptoed in without having turned on the light, with two enormous suitcases by his side. She had been waiting for him at the bottom of the stairs.

I finally understood that when Papa beat Mother, he was also hitting Papi. When we came back from one of our stays with our maternal grandparents, he would correct us for no reason, just for the principle of the thing. No doubt he could see in our eyes that their world fascinated us. I loved everything about their house. The ecstasies of their huge tubs, whereas at home we had to shiver under a shower. The orgies of apple cubes our grandfather provided for us. The huge bookcase in his bedroom, which contained his complete set of Pléiade volumes. The incessant stream of teasing words, uttered in a low voice, his eye benevolent. The nightly depredations I made in the condensed milk he kept for his morning coffee.

One evening when my sisters and I were just coming back from a visit to my grandparents, my father lined us up in front of him, like soldiers being reviewed by their captain, and bellowed out in a martial voice, “So, spoiled children, did you live the high life?”

We didn’t answer anything, in order not to excite him. But he grew heated all by himself.

“You believe that’s real life, the life of châteaus among the filthy rich who fart above their asses! Well, you’re poking your fingers in your eyes.”

My father had an American accent so thick you could cut it with a knife. Like Eddie Constantine, a popular actor in the fifties. But for a foreigner, he had a huge vocabulary, speaking fluent slang, with a sort of voluptuous triviality.

“Your grandfather,” he continued, “doesn’t take himself for a turd, that guy, with his air of having shat all architecture. But he has an asshole like everyone else, the poor idiot.”

I don’t know what my crime could have been, a shrug or an unfortunate word. But Papa’s fist shot out at me. I tried to avoid it, but he knocked me into the hutch right behind me. A key in one of its doors broke the arch over my eyes where the brows are. I still have a scar there to prove it.

I remember the expression on Papa’s face afterward. He looked very bothered, while Mother tried to stanch the blood that flowed everywhere. I don’t think I told on him to the doctor who put in my stitches, but for a long time I displayed my eyebrow wound proudly, like a battle scar.

I certainly hadn’t stolen my punishment; instead of killing Papa, I wounded him often. As he resisted physically, I learned that making fun of him could hurt him more than injuries or blows. My only weapons were the insults I threw in his face, sometimes right in the middle of a meal, just before running away as fast as I could. When he ran after me, he always caught me. But I generally waited to provoke him until the end of the meal, when the wine had gone to his head. He would get up with a terrible scraping of his chair and then sit down again, cursing at me and lashing out against what he called “my stuck-up airs.” Rightly so; I spent my childhood scorning him.

4

Thanks to my father, I learned to live outdoors in any weather, among the beasts, trees, and vegetation. Unable to stand his presence in the house, I often spent entire days in nature, mingling with the great shudder that comes and goes over the world.

Orival Landing, where we lived in Saint-Aubin-lès-Elbeuf, ran along a curve of the Seine. When the weather was nice, it seemed to drown beneath a flood of trees, shrubs, and brambles that were trying to pull themselves up to the sky before they fell back to earth, exhausted, the foliage shining with rain, with dew, or with the slime of snails. Everything there smelled like mud and love, even the people.

Much later, I often encountered that odor at the foot of beds or in damp forests: the smell of the joy of life. Even when it was pouring or the tree branches were covered with frost, I felt that joy underground, a joy of the banks of the Seine, which required, to burst out, only a sunny day, and which, when the day came, would swell the buds, overturn the rocks, and flow toward my feet. That joy enchanted my childhood. I was everything at once: the birds that chirped, the ants that poured out of their hills, the rabbits that danced beneath the brambles, the seeds that creaked with happiness, the wind that ran its fingers through the willows’ hair. I was also the Seine, which let itself flow lazily, half asleep, eight months out of twelve.

I never had to look for God. He was everywhere, in that joy. It seemed to me that I was accompanied and protected. Sometimes, in the midst of the day, because of the wind, the sky, or a smile, I would get carried away by a feeling of ravishment. It was God that called me, I knew it. He never spoke to me, even when I spoke to Him. But I always felt his presence. So the day my mother took me to catechism class for the first time, I was already very devout.

The course was given by the parish priest, a chubby, rosy-cheeked fellow who oozed goodness from every pore: Abbé Mius. He didn’t have any trouble making me into a Catholic. God was for me so obvious, he almost poked you in the eye. I’m sure that, in my mother’s womb, I was already a believer. She transmitted to me a kind of fetal faith, a primal and animal faith—when she spoke about Christ she would have the ecstatic look of a Carmelite.

No doubt she liked sex too much ever to have been tempted to take holy vows. But except for the vow of chastity, I could easily imagine my mother taking the veil and spending her life, a psalter in hand, praying to God. She who never stopped mortifying herself had a hard time accepting the fact, I think, that Christ was a man. I hardly exaggerate when I say that she would eagerly have embraced damnation if only someone would pierce her hands with nails. For lack of anything better, she put them there herself, gradually, with the ecstatic expression of those who adore it when their flesh burns. It did her good to do herself harm.

As an anticlerical in Nietzsche’s manner, my father constantly made fun of my mother’s ostentatious piety. It’s true that she liked to show off her stigmata. Sometimes they had the blue color of the shadows under her eyes, after long days dealing with naps, dirty linen, and crying children. Sometimes they would be green like the bruises inflicted by Papa. Often, in order to be disagreeable, he called her a saint, and I think the word suited her.

Marie-Berthe, called Mabé, saint and martyr. Her greatest happiness would be to be beheaded, or disemboweled, cut up and scattered. She gathered herself together as she could. I understood her better when I was about eleven and found in our library, lost between two huge volumes, doubtless some paternal Hugo or Balzac, a little volume by Simone Weil entitled The Weight of Grace. When the weather was good, I often took the book along with me, in my wanderings along the Seine, to read a few pages surrounded by the beauty of the world. My mother had underlined passages in pencil, as Papi also liked to do.

Thanks to Simone Weil, I understood the virtues of detachment and renunciation, which I saw at work every day when my mother silently absorbed my father’s anger or served herself last at table, or when she didn’t actually give her piece of cake to one of her gluttonous children. Since then, it seems to me I drink from the same well as Mother every time I reread Meister Eckhart’s Treatises and Sermons, Saint Teresa of Ávila’s Life, or Saint John of the Cross’s Spiritual Works.

Except for The Weight of Grace, I never saw any of these books in the house, but Mother sounded exactly like them in different words and conformed to each of their precepts. To find oneself by losing oneself. To renounce everything in order to take possession of oneself. To lower oneself constantly in order to rise up to God.

Mother had the religion of sacrifice and never stopped giving of herself: to her children, to her high school students, to sick or distressed neighbors, to everyone. Her self-denial was almost hysterical.

Some years later, a long time after Mother’s death, I had one of the strongest shocks of my life when I read the autobiography of Saint Marguerite Marie Alacoque. It was my mother speaking to me, her words and her obsessions. With my heart aching, I heard her voice from the grave through the words of the nun arriving at the Monastery of the Visitation, in Paray-le-Monial, in 1671.

The more my love for him is oppressed,

The more I burn for his unique ability to console;

Let me be nightly and daily distressed,

My love for him cannot be removed from my soul;

The more I suffer for his part,

The more he twines me in his heart.

It is in her autobiography that Marguerite Marie recounts that one day, not being able to stand herself for being disgusted by little things, she couldn’t stop herself from licking up the vomit of a patient and eating it while saying to God, “If I had a thousand bodies, a thousand loves, a thousand lives, I would sacrifice them all in order to submit to thee.”

That was exactly Mother. At home, she was the bowel-movement inspector, rolling her eyes in ecstasy when she saw, at the bottom of the pot, her children’s turds. She almost stuck her nose in them. I even heard it said that, at the Liberation, she was not a prudish nurse. She never had to be asked to clean up the sick or the dead. She even tolerated quite well the job of emptying the vat of family excrement. My mother loved shit, because it enabled her to expiate everything and nothing.

5

Rereading my pages up to here, I wonder whether I haven’t fallen into the trap so frequent among writers of memoirs. With a few exceptions, they are either vain or whiny, accusing themselves by beating on the chests of others while recounting all the harm that has been done them.

I, too, have done evil, notably to my father. As I said before, I practically never talked to him. I even turned my back on him, especially when he was down. Long after my mother, the most immediately concerned, had forgiven him his volleys of long ago, I refused to let him off the hook or even to commute the sentence I had given him: perpetual silence. Wrapped up in my idea of vengeance, I always kept my teeth gritted, my face glowering in front of his face, which toward the end was asking for grace.

When he was suffering from bouts of lumbago and shouting loud enough to wake the dead on his sickbed, I didn’t once go up to his room to ask him what I could do to help. Rather, I chuckled to myself. When he was fired from the press at age fifty and saw himself definitively reduced to unemployment, I made no sympathetic gesture toward him, not even a word. He had become invisible to me—except, of course, when I wanted to provoke him. I loved to drive him crazy.

“Did you feed the rabbits?” he growled.

“Obviously.”

“And did you lock the gate on the fence?”

“Obviously.”

“Are you making fun of me?”

“Obviously.”

Obviously was one of those words he couldn’t stand to hear, especially from me. I therefore repeated it as often as possible in an ironic tone of voice. He responded, when I was young, with growls and slaps. While Papa thought before speaking, he never thought before hitting.

But there was nothing to be done; I loved nothing better than getting to him. I formed the habit of adoring everything he detested. Contemporary art. American films. The Catholic Church. French Algeria. It was only to displease him, I understood later, that I finally ended up in journalism, a profession he considered made for embittered people, who usually wrote lying down.

I didn’t dare say to anyone, least of all myself, that I wanted to become a writer. I had therefore chosen substitute careers. Veterinarian, because I loved animals. Trial lawyer, because, like all timid people, I dreamed, in arguing my case, of displaying myself in public. University professor, because, with only a few hours of classes every week, I would be able to give free rein to the great novelist slumbering, I thought, inside me. But the day I discovered that the thought of seeing me a journalist made my father most unhappy, I knew I had found my calling.

He tried to reason with me, showing me that even the greatest journalists never left anything behind, aside from a few witticisms. He described to me a profession eaten up by bitterness. For him, journalists were amnesiac parasites who fed on the droppings of others. Besides, they got everything mixed up. The subsidiary and the essential. Heroes and strutting showoff cocks. Car accidents and large historical cycles. But the more Papa warned me, the more determined and desirous I became. I loved to upset him.

Nevertheless, there was always, until the day of his death, one day in the year when I made peace with my father, one day when I didn’t wish him harm because he wasn’t quite the same. This was Christmas Day. I lowered my guard in front of his smile and his look, almost weepy, when he watched us unwrap our presents at the foot of the tree.

Papa beat us a lot, my mother, my sisters, and me. But he spoiled us the same amount. The more I think of that, the more I regret not having dug and searched inside him to help uncover the goodness he tried all his life to hide, as if it were a nasty sin that was exposed before our eyes at Christmastime.

That good nature reappeared also in very precise circumstances: birthdays; greeting his parents after their annual trip across the Atlantic to see us; what he did for neighbors in need; conversations he had with animals.

However bizarre it may seem, my father was incapable of killing an animal. The only time he tried, it was a real catastrophe. A huge rooster was terrorizing the neighborhood. Papa decided to cut his head off as they did on the midwestern farm where, in his youth, he spent a summer he often spoke of. An American decapitation was, according to him, a less painful method—that is, more civilized—than the French bloodletting which, on Sunday mornings, did indeed fill the air with horrible whimperings and cries of eternal pain in the chicken coops round about.

I was supposed to help, my heart racing, a few steps away from the place of execution. I was four or five, and death interested me. I was not disappointed. The ax indeed fell on the beast’s neck, but it seemed that emotion made Papa lose some of his herculean strength, unless the blade had slipped for some unknown reason. The screaming rooster escaped, flapping his wings, but not, it’s true, puffing out his neck as he was wont to do. We looked for him for a long time in the tall grass where he disappeared. When we found him, he was almost dead, breathing his last on the way to the kitchen. I remember that, once plucked, his skin was blue, like the corpses of those who have greatly suffered.

From the Hardcover edition.

I have to avoid myself. That’s vital. I’ve tried, for several decades now, with a certain success. Once in a while I linger in front of a mirror to check out my blank insomniac face or to find a pimple or a new age spot, but I’ve always stayed away from introspection. I don’t think I could survive psychoanalysis.

This is therefore not an analysis sublimated by writing, as certain novels have tended to be. It is my story, a story I have been careful never to tell myself, for fear I wouldn’t be able to stand it. But I would like today to unroll its thread, now that I have arrived at the sunset of my life, and pay my respects, before I join them, to those who made me.

To my father, most of all. To my father whom I was so ashamed of and with whom I think I never talked. Except maybe to ask him to pass the salt or something at dinner, and even that, I’m not sure of. In the last years of his life, each time he hung around me waiting to start a conversation, I changed rooms. I kept putting off the reconciliation that couldn’t fail to be produced if death hadn’t stolen him from my disaffection.

I had an excuse. My father robbed me of my childhood. It’s because of him that I have always seen the world through adult eyes. Even at the age of five or six, I was already without illusions. As well as I can recollect, I never believed in Santa Claus. It’s hard to believe in Santa Claus in a house where the wife is beaten to a pulp several times a week.

I can’t say when my father began beating my mother, but I knew why. Even when he didn’t find a pretext, he had a reason. He resented the whole world, and my mother most of all, for ruining his life. Papa was an artist, a real one, it seems, and he blamed Mother for preventing him from being the great artist he could feel welling up inside him, by ceaselessly making him children. He didn’t like children. They condemned him to bourgeois mediocrity, which he spat upon every single day. Because of his children he had to renounce his palette and easel in order to spend hours boiling up “commercial art,” an expression that, in his mouth, was always an insult and designated prospectuses, catalogs, or posters.

Mother gave him five children. In a voice too tired not to show its fatigue, he called us “mouths to feed,” so it was impossible to be unaware of the weight we represented on his shoulders, which were nevertheless broad and powerful. He simply beat us cold. He beat us, too, especially me, because I stood up to him more than I could make good on, with the air of a village cock, in order to avenge Mother.

Snapshots of that time show me standing a bit apart from the family, head lowered, seemingly closed off. I wasn’t unhappy, though. My head was already filled with a Good Lord of grass, love, dreams, and beasts, not to speak of the Lord and the Holy Virgin who, from Heaven, watched over me, I believed, like milk on the stove. It was just that I was ravaged by hatred. Hate for my father, whom I imagined myself killing sooner or later.

Papa slept with a knife under his pillow. It was a habit he acquired in the army, after the Normandy landing, when his nights were filled with Germans crawling around to kill Yankees, knives between their teeth.

I imitated him. For a long time, I slept with a pocket knife under my pillow, so as to be able to disembowel my father if he ever made trouble for me at night. Although I thought a lot about this project, I don’t think I would have been able to kill him in cold blood, looking him straight in the eyes. I was too afraid of him.

Papa had a propensity for great anger and great violence. Not with everyone, however. In town, he wouldn’t have hurt a fly. I am even sure he let people step on his toes in the bars of Elbeuf, where he often hung out after work. He was the way immigrants often are. He didn’t want to go back to his country. He was afraid of being noticed, having his work permit confiscated, and being sent back to the United States of America, his mother country, which he hated as much as I venerated it.

At home, on the other hand, anything would set him off, particularly when he came back drunk. He wasn’t a happy drunk; that was the least anyone could say of him. The disappearance of a screwdriver could take on seismic proportions; the walls trembled until he found it where he had left it the day before. Same thing if he discovered that some tool—a trowel or a scythe—had been left out in the rain to rust: a family specialty. At the dinner table, he blew up over nothing, an ambiguous imitation or a furtive smile, and blows rained down like shells at the battle of Gravelotte. We often had to evacuate the wounded, after the meal.

That’s why I had a horror of dinners at home. Nights too, since Papa often waited until the lights were out to slug Mother. Sometimes he bellowed out expletives while he hit her. Other times, he just yelled. There were the sounds of a struggle, furniture moving, doors slamming, but I rarely heard my mother complain while she was being pelted by his fists. Sometimes, muffled screams came out of her, which still pierce my ears, fifty years later. But most of the time, in order not to wake the children, she kept her cries to herself, in the pit of her stomach, where they fed a cancer that was biding its time.

On those nights I stayed in bed, my heart beating, my blood frozen, trembling like a leaf. I was dying. I think one always dies a little when one hears one’s mother beaten. I spent a part of my childhood dying, but only part. In the other part, of course, I grew stronger.

2

I’m not sure how old I was, maybe four or five, maybe more, but I remember that it was raining hard and my brothers were not yet born. It was a summer night, in Italy, on the side of Venice where my father liked to spend vacations. We found ourselves, Papa, Mother, my two sisters, and I, in the family car, a Renault that was built like a big bicycle. My mother was reading the road map with a flashlight in her hand, in order to indicate our route to my father, who was in a bad mood because of the bad weather.

“Where are you taking us?” bellowed my father suddenly. “We just passed by here!”

“I don’t think so.”

“You’re making us go around in circles. Don’t you recognize this intersection?”

He stopped the car on the shoulder and grabbed the map and the flashlight from my mother. He concentrated a long time while sighing noisily, because he only did things halfway, before muttering, “You’re wrong again. You don’t even know how to read a map.”

“You’re the one who doesn’t know how to follow my instructions.”

For that act of insolence, Mother got a first blow that knocked her against the car window. Papa didn’t know how to control his strength. He always hit harder than he intended to. His slaps were like punches.

My mother, despite the schoolgirl masochism that was eating her up and that I’ll come back to, sometimes had a good comeback. She muttered calmly, which made her case worse, “If you think that is how you’ll find your way, old man—”

She received a new blow, even stronger than the first, to judge by the sound she made: a dull sound, like the sound red meat makes when the butcher throws it on his worktable before cutting it up. Nevertheless, she didn’t consider the discussion over.

“You beast!” she cried.

Third blow, same dull sound. But this time Mother gathered herself up. There were limits to her masochism. She threw herself against Papa’s chest, screaming and drumming against him like an angry child. I always felt very afraid when my mother resisted like that. She wasn’t up to it.

If I remember correctly—and I think I do, at least when it comes to this event—that night my mother did not, as she often had in the past, reproach my father for beating her in front of the children. In fact I’m sure the thought never entered her head. That was when we were beginning to get used to Papa’s rages.

His muscles reacted first. Especially the hand muscles, to be precise. The head followed. One could never look for my father as cause of an action. He no longer answered for anything. For a trifle, he could have killed my mother without intending to, just by punching her wrong. That was why it was my duty as the eldest to kill him before he committed the irreparable.

I didn’t yet have the bulk to stand up to him, but I bided my time, to be sure to accomplish my design. With a knife, with an ax, with a mallet; I hadn’t yet chosen the instrument. However it happened, I at least knew that my father would suffer a thousand deaths, and maybe more.

That’s what I said to myself, that night, on the backseat of the Renault, while I pouted and Papa riddled Mother with punches. He hit her while breathing heavily, and heaved a logger’s groan each time he struck a blow. He applied himself to the task, for he didn’t take anything lightly, especially vacations.

Mother was crying, all wrapped up in her own body, protecting her head with her arms. She was crying without ostentation under the volley of blows, waiting for it to be over. Years later, on reading Ecclesiastes, I understood my mother’s philosophy. For her, there was a time for everything: a time to tear and a time to mend, a time to love and a time to hate. For nothing under the sun can last, neither happiness nor unhappiness. I knew then that she had been much stronger than he was.

It goes without saying that we were crying too, my sisters and I. My father, who ordinarily couldn’t stand the sound of children crying, let us wail our eyes out when he beat Mother. At the time, I thought he was too busy correcting Mother to have time to tell us to shut up. Now, after considering it some more, I think it was his way of telling us we were right.

Papa had extinguished the flashlight, no doubt so as not to use up the battery, during this session with Mother. I could see nothing in the darkness, but I remember that at a given moment my father took my mother’s nose and gave it a twist, unless he crushed it, but if so, the damage would have been visible the next day, and it wasn’t.

“You beast!” cried my mother again, using her favorite insult. “You’ve broken my nose!”

“That’ll teach you.”

“You can just manage on your own now.”

That was the one thing that should never be said. But against all expectations, Papa decided to stop his attack. He acted like someone who hadn’t heard anything and continued on his way without saying a word.

It was still raining when we reached our destination, a second-class campground like all those where we spent our vacations, in the midst of the smell of soap and dirty water. Papa thought it prudent not to put up the tent on its stakes, so all five of us slept, all tangled up, in the family car, in the silence that comes after a storm.

The following day, Papa uncorked some Lambrusco and some Asti Spumante. He was ashamed. My father was always submerged in shame, afterward. He could look at no one and spent hours without unclenching his teeth. That suited us perfectly. No one spoke to him, either. As for me, I had a good reason to keep quiet. I was too busy replaying the film of the fight and planning my revenge. It was the following night, I think, that I wet the bed for the last time.

3

The air was very heavy in our house along the Seine, in Saint-Aubin-lès-Elbeuf. Over everything there reigned a certain violence that crushed you, at least when my father was there. That was surely the reason I developed the bad habit of breathing economically, in little gasps, like a person with asthma.

To this day it sometimes happens that I forget to breathe. My turn goes by. Thus I live between two apneas, more or less. If it were not for the bright lights on the sides of my eyes and the sensation of suffocating—which, from time to time, recall me to order—I think I would have died of asphyxiation long ago.

Often, Mother sent us to her parents’ house, just over a mile away from ours, to unwind a bit. They lived in an enormous apartment over the Allain Press, named after my grandfather, an austere boss, his thin hair slicked back, his eyeglasses stern, his mustache square, who was constantly working and, in order to apologize for that, showered his descendants with gifts.

Most of the time, generosity is just disguised indifference, a way to buy tranquillity. That could not have been true of Papi, as we called him. He had real goodness in his look and smile, and a kind of sweet and attentive irony escaped him, for he sought above all to give the impression, even within the family, that he was uncompromisingly stiff and rigid.

I adored Papi. There was something pathetic about his desire for his twenty grandchildren, with their mothers, to spend at least part of their summer vacations together in a big house that he rented for them in Normandy or Brittany. Or about the interminable dinner parties he organized, made up of family friends and distant cousins. He might have seemed to be seeking a kind of posterity for himself. But he was too proud to have room to be vain, too.

He doubtless foresaw that someday a great seismic event, his death or something else, would devastate everything he had patiently built up over the years: the press, the family, the dynasty. He was too imbued with the ancients he was always reading—Plato or Plutarch—to nourish the illusion that one could leave any trace of oneself on this earth. He didn’t believe in God any more than in the future. His children discovered this rather starkly when they opened his will and read that he was a Christian but not a believer, he wanted to be buried in secret at sun- set, and he wanted to go directly from the house to the cemetery.

Up till then, Papi had always acted like a model parishioner, a great consumer of hosts. That was how I learned that one knows very little about other people before their deaths, even one’s own grandfather. Once they have mounted the stage boards of life, they continue, up until the last speech, to play a character in whom they have ceased to believe. Not wanting to rock the boat, Papi let those who were familiar with his will be his judges and either carry out or not carry out his wishes. They, of course, covered what he said with a handkerchief.

I have spoken of Papi’s goodness. But however sociable he was, he couldn’t stand to have anyone put his authority in question. Not the typographical union leaders, whom he fired without hesitating. Not my father, who worked for his press in the “department of design,” as we called it. I don’t think Papi took advantage of his position to humiliate his son-in-law, but Papa had contestation in his blood, fueled by his passion for American writers like Upton Sinclair, John Dos Passos, and John Steinbeck.

Papa was not a Marxist. He felt a merciless hatred, in fact, for Communists and their fellow travelers, whom he accused of sowing death wherever they went. I heard him say once that he would fear for his life if they ever came to power in France thanks to an invasion by the Soviet Union—a hypothesis, by the way, that he imagined seriously. But at the same time, he loathed bosses most of all, and all those who, like my grandfather, believed they had come—it was one of his favorite expressions—directly out of “Jupiter’s thigh.”

My grandfather certainly had no idea how much Papa hated him, because, as was his wont, Papa said bad things about him only behind his back—that is, in front of us, at home. Papa accused him of everything—greed, stinginess, tyranny, meanness—and, which didn’t make things any easier, he was also jealous of him. He couldn’t abide their conspiratorial tones and low voices when Papi and Mother exchanged books, magazines, smiles, or secrets.

That is no doubt the reason he got along so well with my maternal grandmother. They both shared, I think, the same hatred of Papi. The same passion for music, too. Winner of first place at the Paris conservatory, Mamie made me cry when she played, with ineffable skill, Bach or Dupré, her great friend, on the organs of the churches of Elbeuf.

But she did everything to kill the artist in her. Except when she was in front of an organ, once or twice a month, not much remained of the musician Papi thought he’d married, inflamed as he was from the moment he laid eyes on her, the great Romantic, seeing the sad-eyed girl with the prominent eyeballs whose blind father was a piano tuner. He asked her to respond to his marriage proposal in music: If the answer was yes, she was to play a Bach fugue at Sunday mass. She played the fugue.

As the years passed, Mamie drowned in masochism, that family curse. Once funny, lively, and cultivated, her heart in her hand, a pelican’s heart, she was subject to sudden absurd outbursts, over a laundry mark or insipid friends. She repeated the same expressions all day long; for example, about her grandchildren: “It’s scary how cute he is.” She confined the perimeter of her conversation to the babies, the clothes, the vacuum cleaners, and the cleaning products, while keeping, nevertheless, down to her last drop of life, each time she took her place at a keyboard, the same magic at the tips of her fingers. Papi took a mistress in Paris and loved her passionately. He fled regularly to Italy, where he always spent vacations with her, around Lake Como. He sent us postcards saying “love and kisses.”

Mamie often confronted him with scenes of jealousy. I even saw her slap my grandfather around one Sunday night when he tiptoed in without having turned on the light, with two enormous suitcases by his side. She had been waiting for him at the bottom of the stairs.

I finally understood that when Papa beat Mother, he was also hitting Papi. When we came back from one of our stays with our maternal grandparents, he would correct us for no reason, just for the principle of the thing. No doubt he could see in our eyes that their world fascinated us. I loved everything about their house. The ecstasies of their huge tubs, whereas at home we had to shiver under a shower. The orgies of apple cubes our grandfather provided for us. The huge bookcase in his bedroom, which contained his complete set of Pléiade volumes. The incessant stream of teasing words, uttered in a low voice, his eye benevolent. The nightly depredations I made in the condensed milk he kept for his morning coffee.

One evening when my sisters and I were just coming back from a visit to my grandparents, my father lined us up in front of him, like soldiers being reviewed by their captain, and bellowed out in a martial voice, “So, spoiled children, did you live the high life?”

We didn’t answer anything, in order not to excite him. But he grew heated all by himself.

“You believe that’s real life, the life of châteaus among the filthy rich who fart above their asses! Well, you’re poking your fingers in your eyes.”

My father had an American accent so thick you could cut it with a knife. Like Eddie Constantine, a popular actor in the fifties. But for a foreigner, he had a huge vocabulary, speaking fluent slang, with a sort of voluptuous triviality.

“Your grandfather,” he continued, “doesn’t take himself for a turd, that guy, with his air of having shat all architecture. But he has an asshole like everyone else, the poor idiot.”

I don’t know what my crime could have been, a shrug or an unfortunate word. But Papa’s fist shot out at me. I tried to avoid it, but he knocked me into the hutch right behind me. A key in one of its doors broke the arch over my eyes where the brows are. I still have a scar there to prove it.

I remember the expression on Papa’s face afterward. He looked very bothered, while Mother tried to stanch the blood that flowed everywhere. I don’t think I told on him to the doctor who put in my stitches, but for a long time I displayed my eyebrow wound proudly, like a battle scar.

I certainly hadn’t stolen my punishment; instead of killing Papa, I wounded him often. As he resisted physically, I learned that making fun of him could hurt him more than injuries or blows. My only weapons were the insults I threw in his face, sometimes right in the middle of a meal, just before running away as fast as I could. When he ran after me, he always caught me. But I generally waited to provoke him until the end of the meal, when the wine had gone to his head. He would get up with a terrible scraping of his chair and then sit down again, cursing at me and lashing out against what he called “my stuck-up airs.” Rightly so; I spent my childhood scorning him.

4

Thanks to my father, I learned to live outdoors in any weather, among the beasts, trees, and vegetation. Unable to stand his presence in the house, I often spent entire days in nature, mingling with the great shudder that comes and goes over the world.

Orival Landing, where we lived in Saint-Aubin-lès-Elbeuf, ran along a curve of the Seine. When the weather was nice, it seemed to drown beneath a flood of trees, shrubs, and brambles that were trying to pull themselves up to the sky before they fell back to earth, exhausted, the foliage shining with rain, with dew, or with the slime of snails. Everything there smelled like mud and love, even the people.

Much later, I often encountered that odor at the foot of beds or in damp forests: the smell of the joy of life. Even when it was pouring or the tree branches were covered with frost, I felt that joy underground, a joy of the banks of the Seine, which required, to burst out, only a sunny day, and which, when the day came, would swell the buds, overturn the rocks, and flow toward my feet. That joy enchanted my childhood. I was everything at once: the birds that chirped, the ants that poured out of their hills, the rabbits that danced beneath the brambles, the seeds that creaked with happiness, the wind that ran its fingers through the willows’ hair. I was also the Seine, which let itself flow lazily, half asleep, eight months out of twelve.

I never had to look for God. He was everywhere, in that joy. It seemed to me that I was accompanied and protected. Sometimes, in the midst of the day, because of the wind, the sky, or a smile, I would get carried away by a feeling of ravishment. It was God that called me, I knew it. He never spoke to me, even when I spoke to Him. But I always felt his presence. So the day my mother took me to catechism class for the first time, I was already very devout.

The course was given by the parish priest, a chubby, rosy-cheeked fellow who oozed goodness from every pore: Abbé Mius. He didn’t have any trouble making me into a Catholic. God was for me so obvious, he almost poked you in the eye. I’m sure that, in my mother’s womb, I was already a believer. She transmitted to me a kind of fetal faith, a primal and animal faith—when she spoke about Christ she would have the ecstatic look of a Carmelite.

No doubt she liked sex too much ever to have been tempted to take holy vows. But except for the vow of chastity, I could easily imagine my mother taking the veil and spending her life, a psalter in hand, praying to God. She who never stopped mortifying herself had a hard time accepting the fact, I think, that Christ was a man. I hardly exaggerate when I say that she would eagerly have embraced damnation if only someone would pierce her hands with nails. For lack of anything better, she put them there herself, gradually, with the ecstatic expression of those who adore it when their flesh burns. It did her good to do herself harm.

As an anticlerical in Nietzsche’s manner, my father constantly made fun of my mother’s ostentatious piety. It’s true that she liked to show off her stigmata. Sometimes they had the blue color of the shadows under her eyes, after long days dealing with naps, dirty linen, and crying children. Sometimes they would be green like the bruises inflicted by Papa. Often, in order to be disagreeable, he called her a saint, and I think the word suited her.

Marie-Berthe, called Mabé, saint and martyr. Her greatest happiness would be to be beheaded, or disemboweled, cut up and scattered. She gathered herself together as she could. I understood her better when I was about eleven and found in our library, lost between two huge volumes, doubtless some paternal Hugo or Balzac, a little volume by Simone Weil entitled The Weight of Grace. When the weather was good, I often took the book along with me, in my wanderings along the Seine, to read a few pages surrounded by the beauty of the world. My mother had underlined passages in pencil, as Papi also liked to do.

Thanks to Simone Weil, I understood the virtues of detachment and renunciation, which I saw at work every day when my mother silently absorbed my father’s anger or served herself last at table, or when she didn’t actually give her piece of cake to one of her gluttonous children. Since then, it seems to me I drink from the same well as Mother every time I reread Meister Eckhart’s Treatises and Sermons, Saint Teresa of Ávila’s Life, or Saint John of the Cross’s Spiritual Works.

Except for The Weight of Grace, I never saw any of these books in the house, but Mother sounded exactly like them in different words and conformed to each of their precepts. To find oneself by losing oneself. To renounce everything in order to take possession of oneself. To lower oneself constantly in order to rise up to God.

Mother had the religion of sacrifice and never stopped giving of herself: to her children, to her high school students, to sick or distressed neighbors, to everyone. Her self-denial was almost hysterical.

Some years later, a long time after Mother’s death, I had one of the strongest shocks of my life when I read the autobiography of Saint Marguerite Marie Alacoque. It was my mother speaking to me, her words and her obsessions. With my heart aching, I heard her voice from the grave through the words of the nun arriving at the Monastery of the Visitation, in Paray-le-Monial, in 1671.

The more my love for him is oppressed,

The more I burn for his unique ability to console;

Let me be nightly and daily distressed,

My love for him cannot be removed from my soul;

The more I suffer for his part,

The more he twines me in his heart.

It is in her autobiography that Marguerite Marie recounts that one day, not being able to stand herself for being disgusted by little things, she couldn’t stop herself from licking up the vomit of a patient and eating it while saying to God, “If I had a thousand bodies, a thousand loves, a thousand lives, I would sacrifice them all in order to submit to thee.”

That was exactly Mother. At home, she was the bowel-movement inspector, rolling her eyes in ecstasy when she saw, at the bottom of the pot, her children’s turds. She almost stuck her nose in them. I even heard it said that, at the Liberation, she was not a prudish nurse. She never had to be asked to clean up the sick or the dead. She even tolerated quite well the job of emptying the vat of family excrement. My mother loved shit, because it enabled her to expiate everything and nothing.

5

Rereading my pages up to here, I wonder whether I haven’t fallen into the trap so frequent among writers of memoirs. With a few exceptions, they are either vain or whiny, accusing themselves by beating on the chests of others while recounting all the harm that has been done them.

I, too, have done evil, notably to my father. As I said before, I practically never talked to him. I even turned my back on him, especially when he was down. Long after my mother, the most immediately concerned, had forgiven him his volleys of long ago, I refused to let him off the hook or even to commute the sentence I had given him: perpetual silence. Wrapped up in my idea of vengeance, I always kept my teeth gritted, my face glowering in front of his face, which toward the end was asking for grace.

When he was suffering from bouts of lumbago and shouting loud enough to wake the dead on his sickbed, I didn’t once go up to his room to ask him what I could do to help. Rather, I chuckled to myself. When he was fired from the press at age fifty and saw himself definitively reduced to unemployment, I made no sympathetic gesture toward him, not even a word. He had become invisible to me—except, of course, when I wanted to provoke him. I loved to drive him crazy.

“Did you feed the rabbits?” he growled.

“Obviously.”

“And did you lock the gate on the fence?”

“Obviously.”

“Are you making fun of me?”

“Obviously.”

Obviously was one of those words he couldn’t stand to hear, especially from me. I therefore repeated it as often as possible in an ironic tone of voice. He responded, when I was young, with growls and slaps. While Papa thought before speaking, he never thought before hitting.

But there was nothing to be done; I loved nothing better than getting to him. I formed the habit of adoring everything he detested. Contemporary art. American films. The Catholic Church. French Algeria. It was only to displease him, I understood later, that I finally ended up in journalism, a profession he considered made for embittered people, who usually wrote lying down.

I didn’t dare say to anyone, least of all myself, that I wanted to become a writer. I had therefore chosen substitute careers. Veterinarian, because I loved animals. Trial lawyer, because, like all timid people, I dreamed, in arguing my case, of displaying myself in public. University professor, because, with only a few hours of classes every week, I would be able to give free rein to the great novelist slumbering, I thought, inside me. But the day I discovered that the thought of seeing me a journalist made my father most unhappy, I knew I had found my calling.

He tried to reason with me, showing me that even the greatest journalists never left anything behind, aside from a few witticisms. He described to me a profession eaten up by bitterness. For him, journalists were amnesiac parasites who fed on the droppings of others. Besides, they got everything mixed up. The subsidiary and the essential. Heroes and strutting showoff cocks. Car accidents and large historical cycles. But the more Papa warned me, the more determined and desirous I became. I loved to upset him.

Nevertheless, there was always, until the day of his death, one day in the year when I made peace with my father, one day when I didn’t wish him harm because he wasn’t quite the same. This was Christmas Day. I lowered my guard in front of his smile and his look, almost weepy, when he watched us unwrap our presents at the foot of the tree.

Papa beat us a lot, my mother, my sisters, and me. But he spoiled us the same amount. The more I think of that, the more I regret not having dug and searched inside him to help uncover the goodness he tried all his life to hide, as if it were a nasty sin that was exposed before our eyes at Christmastime.

That good nature reappeared also in very precise circumstances: birthdays; greeting his parents after their annual trip across the Atlantic to see us; what he did for neighbors in need; conversations he had with animals.

However bizarre it may seem, my father was incapable of killing an animal. The only time he tried, it was a real catastrophe. A huge rooster was terrorizing the neighborhood. Papa decided to cut his head off as they did on the midwestern farm where, in his youth, he spent a summer he often spoke of. An American decapitation was, according to him, a less painful method—that is, more civilized—than the French bloodletting which, on Sunday mornings, did indeed fill the air with horrible whimperings and cries of eternal pain in the chicken coops round about.

I was supposed to help, my heart racing, a few steps away from the place of execution. I was four or five, and death interested me. I was not disappointed. The ax indeed fell on the beast’s neck, but it seemed that emotion made Papa lose some of his herculean strength, unless the blade had slipped for some unknown reason. The screaming rooster escaped, flapping his wings, but not, it’s true, puffing out his neck as he was wont to do. We looked for him for a long time in the tall grass where he disappeared. When we found him, he was almost dead, breathing his last on the way to the kitchen. I remember that, once plucked, his skin was blue, like the corpses of those who have greatly suffered.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“[An] astonishingly frank memoir of self-discovery and self-loathing.” –The Philadelphia Inquirer

“Says as much about the events in Normandy in 1944 as do many of the far weightier texts that it can honorably sit beside.”

–The Economist

“What Giesbert does well in his work . . . is to instill his prose with the haunting that forever chases the abused child, long after that child becomes an adult.” –Rocky Mountain News

“This dark story, in the tradition of Maupassant, is a miracle: gaiety, imagination, the drive to understand, and also tenderness. . . . It has perhaps never been better show how war continues long after its end and is spread from father to son.” –Le Nouvel Observateur

“Says as much about the events in Normandy in 1944 as do many of the far weightier texts that it can honorably sit beside.”

–The Economist

“What Giesbert does well in his work . . . is to instill his prose with the haunting that forever chases the abused child, long after that child becomes an adult.” –Rocky Mountain News

“This dark story, in the tradition of Maupassant, is a miracle: gaiety, imagination, the drive to understand, and also tenderness. . . . It has perhaps never been better show how war continues long after its end and is spread from father to son.” –Le Nouvel Observateur

Descriere

This poignant, taunt, harrowing childhood memoir, already a controversial bestseller in Europe, describes a Frenchman's dark relationship with his abusive American father.