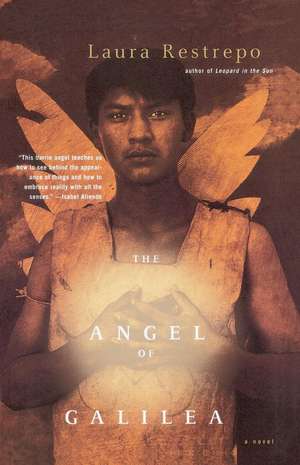

The Angel of Galilea

Autor Laura Restrepo Traducere de Dolores M. Kochen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 1999

"Laura Restrepo breathes life into a singular amalgam of journalistic investigation and literary creation. Her fascination with popular culture and the play of her impeccable humor, of that biting but at the same time tender irony . . . infuses them with unmistakable reading pleasures." --Gabriel García Márquez

Winner of Mexico's Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Prize, and France's Prix France Culture, The Angel of Galilea introduces a refreshing new voice in Latin American literature to the English speaking audience.

Mona is a jaded reporter for a Colombian tabloid sent on assignment to investigate an angel sighting in one of Bogotá's most devastated barrios, where she encounters a community torn apart by a passionate conflict over a beautiful man who walks the fine line between sanity and sainthood. For the people of Galilea, this mysterious and sensual "angel without a name" represents their hope amidst desperate circumstances; for Mona, he awakens her desire to love and gives her a reason to believe. When the barrio's priest leads a revolt against the fallen angel, Mona risks everything to protect him from the gang that threatens to destroy him.

"Restrepo is a writer to treasure." --Alastair Reid

"Sharply resonant." --The New York Times Book Review

"Surprising, wonderful, and, for me, deeply moving."

--Alvaro Mutis

Preț: 88.47 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 133

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.93€ • 17.72$ • 14.01£

16.93€ • 17.72$ • 14.01£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 17-31 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375706493

ISBN-10: 0375706496

Pagini: 208

Dimensiuni: 141 x 221 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Ediția:Vintage Intl.

Editura: Vintage Publishing

ISBN-10: 0375706496

Pagini: 208

Dimensiuni: 141 x 221 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Ediția:Vintage Intl.

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Notă biografică

Laura Restrepo has been very active in politics and journalism throughout Latin America and has lived in Colombia, Argentina, Mexico, and Spain. She was professor of literature at the National University of Colombia as well as political editor of the weekly magazine Semana. She is the author of several novels, including El Leopardo al Sol (Leopard in the Sun, forthcoming from Crown). She currently lives in Bogotá, Colombia.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Orifiel, Angel of Light

There were no warning signs of what was about to happen. Or maybe there were, but I was unable to interpret them. In reconstructing the sequence of events, I recall that a few days before it all started, three men raped a crazy woman in the garden in front of my building. It was around then that my neighbor's dog vaulted from a third-story window, landed on the street, and walked away unharmed. And the leper who sells lottery tickets on the corner of 92nd and 15th streets gave birth to a healthy, beautiful baby. Surely those were signs, among many others, but then again this insane city gives off so many doomsday warnings that no one pays attention anymore. And I live in what is considered a middle-class neighborhood: one can only imagine the number of omens that crop up daily in the shantytowns.

The truth is that this story, with its supernatural echoes, which would so deeply transform my life, began at eight o'clock on a very ordinary Monday morning when, in a lousy mood, I arrived at the editorial offices of Somos magazine, where I worked as a reporter. Feeling certain that my boss was about to give me a particularly loathsome assignment, Id been dreading this moment all weekend. I was sure he would send me to cover the national beauty pageant that was getting under way in Cartagena. I was younger then, full of energy and ambition, and determined to write about things that mattered, but fate had dealt me a cruel blow, forcing me to earn my living at one of the many popular weekly tabloids.

Of all my assignments at Somos, covering the pageant was by far the worst. It was an unnerving task to interview thirty girls with wasp waists and wasp-size brains to match. I also have to admit that their abundant youth and trim figures wounded my pride. Even more painful was having to rhapsodize on Miss Bocayás Pepsodent smile, Miss Tolimas dubious virginity, and Miss Araucas preoccupation with poor children. To top it all, the beauty queens tried so hard to project a charming, naive image that they dealt with everyone on a first-name basis, kissing us, swinging their hips, bubbling over with sweetness. They even had a special name for the reporters from Somos: Sommie, while you're interviewing me, hold my mirror so I can put on my makeup. Take this down, Sommie: My favorite person in the world is Mother Teresa of Calcutta. And there I'd be, standing in front of this splendid five-foot-ten figure, scribbling down streams of nonsense.

No. This year I was going to refuse to cover the pageant, even if it cost me my job. Devouring a bowl of earthworms would be preferable to being called Sommie one more time or doing Miss Cundinamarca the favor of fetching the earrings she left in the dining room. So I entered the editor's office cursing under my breath; unfortunately, I knew only too well that it would be impossible to find another steady job and, therefore, to resign was out of the question.

At the far side of the room I spotted the familiar bottle-green corduroy jacket, and I thought, now the jacket will turn around to reveal, turkey neck and all, none other than my boss who, without greeting me, will bark out orders to pack for Cartagena--and off goes Sommie again, having to swallow her worms whole. The jacket turned around, and the turkey looked at me, but contrary to my expectations, he condescended to wish me good morning, and not a word about Cartagena. Instead he demanded something else, which I did not like any better.

"Get out to the Galilea district right away. An angels been sighted."

"What angel?"

"Whatever. I need a piece on angels."

Now Colombia happens to be the country in the world with the most miracles per square foot. All virgins descend from Heaven, all Christs shed tears, invisible surgeons perform appendectomies on the faithful, and soothsayers predict winning lottery numbers. This is all routine: we maintain a direct line with the other world, and can only survive as a nation with a daily megadose of superstition. We have always enjoyed an international monopoly on irrational and paranormal events. And yet the editor in chief wanted a piece on angel sightings now--not a month earlier or a month later--merely because the topic was no longer hot in the United States.

A few months ago, the end-of-millennium and New Age winds had stirred a veritable angelic frenzy in the States. Hundreds of people had claimed to have had contact with one angel or another. Eminent scientists attested to their presence, and even the first lady, moved by the general enthusiasm, sported a brooch of cherub wings on her lapel. As usual, Americans were flogging the topic to the point of exhaustion. Eventually, the first lady dropped her wings and returned to her more classic jewelry, the scientists came back to earth, and the T-shirts printed with plump little Raphaelite angels were put on sale at half price. That signaled that it was now our turn, here in Colombia. We pick up what is already passé in Miami. Astonishing, isnt it, that we journalists spend most of our time warming up topics already cold in the United States.

Despite everything, I did not complain.

"Why the Galilea district?" I wanted to know.

"There's a woman from Galilea who comes several days a week to wash clothes for one of my wife's aunts. This woman told her about the angel. So, go out there now and get the story however you can, even if you have to make it up. And take photos, plenty of photos. Next week well put it on the cover."

"Can you give me a name, or an address? Any concrete details?"

"Nothing, you'll have to figure it out. What the heck do I know? When you see someone with wings, that's your angel."

Galilea. It must be one of the countless neighborhoods in the south of the city, miserable, overcrowded, devastated by gangs of youths. But its name was Galilea, and ever since I was a child, biblical names have had the power to move me. Every night before I went to bed, until I was twelve or thirteen, my grandfather used to read me a passage from the Old Testament or the Gospels. I listened, mesmerized, without understanding much but lulled by the whir of his r's, which, as an old Belgian, he could never pronounce well in Spanish.

My grandfather would fall asleep halfway through his recitation, and I, entranced, would then repeat fragments from his evocative reading: Samaria, Galilee, Jacob, Rachel, Wedding at Cana, Sea of Tiberias, Mary Magdalene, Esau, Gethsemane, and the whole litany of names, ancient and mysterious, would waft its way through my bedroom in the darkness. Some words were terrifying and presaged destruction, like Mane, Thecel, and Phares, though I still do not know what they mean; others sounded incredibly harsh, like noli me tangere, which was what Jesus said to Mary Magdalene after his resurrection.

Even today, biblical names seem like talismans for me. Though I must admit that despite my grandfather's readings, and my own baptism and Christian upbringing, I was not a practicing Christian, perhaps not even a believer. And that is still the case: I must stress this from the outset so that nobody will be thinking, let alone hoping, that this is the story of a religious conversion.

I confess that when my boss said "Galilea," the word at first meant nothing to me, perhaps because the annoying way he pronounced the word robbed it of its power. And biblical names were usually relegated to our poorest neighborhoods--Belencito, Siloé, Nazaret--so I didnt give it a second thought.

Twenty minutes later I was in a taxi, heading for Galilea. The driver had never even heard of the place and had to radio for directions.

All I knew about angels was a prayer I used to recite as a child:

Sweet Guardian Angel

My heavenly guide

Hovering, night and day

Gently by my side.

My only contact with angels had been in grade school, at a procession on the thirteenth of May in honor of the Virgin Mary, and it had not turned out well. It so happened that one year, for being such a model student, my best friend, Marie Chris Cortés, had been chosen to be part of the Celestial Legion and had to wear an angel costume with a pair of very real-looking wings, which her mother had made for her out of real feathers. When I saw her, I laughed, and told her she looked more like a chicken than an angel, which was true.

--Translated by Dolores M. Koch

There were no warning signs of what was about to happen. Or maybe there were, but I was unable to interpret them. In reconstructing the sequence of events, I recall that a few days before it all started, three men raped a crazy woman in the garden in front of my building. It was around then that my neighbor's dog vaulted from a third-story window, landed on the street, and walked away unharmed. And the leper who sells lottery tickets on the corner of 92nd and 15th streets gave birth to a healthy, beautiful baby. Surely those were signs, among many others, but then again this insane city gives off so many doomsday warnings that no one pays attention anymore. And I live in what is considered a middle-class neighborhood: one can only imagine the number of omens that crop up daily in the shantytowns.

The truth is that this story, with its supernatural echoes, which would so deeply transform my life, began at eight o'clock on a very ordinary Monday morning when, in a lousy mood, I arrived at the editorial offices of Somos magazine, where I worked as a reporter. Feeling certain that my boss was about to give me a particularly loathsome assignment, Id been dreading this moment all weekend. I was sure he would send me to cover the national beauty pageant that was getting under way in Cartagena. I was younger then, full of energy and ambition, and determined to write about things that mattered, but fate had dealt me a cruel blow, forcing me to earn my living at one of the many popular weekly tabloids.

Of all my assignments at Somos, covering the pageant was by far the worst. It was an unnerving task to interview thirty girls with wasp waists and wasp-size brains to match. I also have to admit that their abundant youth and trim figures wounded my pride. Even more painful was having to rhapsodize on Miss Bocayás Pepsodent smile, Miss Tolimas dubious virginity, and Miss Araucas preoccupation with poor children. To top it all, the beauty queens tried so hard to project a charming, naive image that they dealt with everyone on a first-name basis, kissing us, swinging their hips, bubbling over with sweetness. They even had a special name for the reporters from Somos: Sommie, while you're interviewing me, hold my mirror so I can put on my makeup. Take this down, Sommie: My favorite person in the world is Mother Teresa of Calcutta. And there I'd be, standing in front of this splendid five-foot-ten figure, scribbling down streams of nonsense.

No. This year I was going to refuse to cover the pageant, even if it cost me my job. Devouring a bowl of earthworms would be preferable to being called Sommie one more time or doing Miss Cundinamarca the favor of fetching the earrings she left in the dining room. So I entered the editor's office cursing under my breath; unfortunately, I knew only too well that it would be impossible to find another steady job and, therefore, to resign was out of the question.

At the far side of the room I spotted the familiar bottle-green corduroy jacket, and I thought, now the jacket will turn around to reveal, turkey neck and all, none other than my boss who, without greeting me, will bark out orders to pack for Cartagena--and off goes Sommie again, having to swallow her worms whole. The jacket turned around, and the turkey looked at me, but contrary to my expectations, he condescended to wish me good morning, and not a word about Cartagena. Instead he demanded something else, which I did not like any better.

"Get out to the Galilea district right away. An angels been sighted."

"What angel?"

"Whatever. I need a piece on angels."

Now Colombia happens to be the country in the world with the most miracles per square foot. All virgins descend from Heaven, all Christs shed tears, invisible surgeons perform appendectomies on the faithful, and soothsayers predict winning lottery numbers. This is all routine: we maintain a direct line with the other world, and can only survive as a nation with a daily megadose of superstition. We have always enjoyed an international monopoly on irrational and paranormal events. And yet the editor in chief wanted a piece on angel sightings now--not a month earlier or a month later--merely because the topic was no longer hot in the United States.

A few months ago, the end-of-millennium and New Age winds had stirred a veritable angelic frenzy in the States. Hundreds of people had claimed to have had contact with one angel or another. Eminent scientists attested to their presence, and even the first lady, moved by the general enthusiasm, sported a brooch of cherub wings on her lapel. As usual, Americans were flogging the topic to the point of exhaustion. Eventually, the first lady dropped her wings and returned to her more classic jewelry, the scientists came back to earth, and the T-shirts printed with plump little Raphaelite angels were put on sale at half price. That signaled that it was now our turn, here in Colombia. We pick up what is already passé in Miami. Astonishing, isnt it, that we journalists spend most of our time warming up topics already cold in the United States.

Despite everything, I did not complain.

"Why the Galilea district?" I wanted to know.

"There's a woman from Galilea who comes several days a week to wash clothes for one of my wife's aunts. This woman told her about the angel. So, go out there now and get the story however you can, even if you have to make it up. And take photos, plenty of photos. Next week well put it on the cover."

"Can you give me a name, or an address? Any concrete details?"

"Nothing, you'll have to figure it out. What the heck do I know? When you see someone with wings, that's your angel."

Galilea. It must be one of the countless neighborhoods in the south of the city, miserable, overcrowded, devastated by gangs of youths. But its name was Galilea, and ever since I was a child, biblical names have had the power to move me. Every night before I went to bed, until I was twelve or thirteen, my grandfather used to read me a passage from the Old Testament or the Gospels. I listened, mesmerized, without understanding much but lulled by the whir of his r's, which, as an old Belgian, he could never pronounce well in Spanish.

My grandfather would fall asleep halfway through his recitation, and I, entranced, would then repeat fragments from his evocative reading: Samaria, Galilee, Jacob, Rachel, Wedding at Cana, Sea of Tiberias, Mary Magdalene, Esau, Gethsemane, and the whole litany of names, ancient and mysterious, would waft its way through my bedroom in the darkness. Some words were terrifying and presaged destruction, like Mane, Thecel, and Phares, though I still do not know what they mean; others sounded incredibly harsh, like noli me tangere, which was what Jesus said to Mary Magdalene after his resurrection.

Even today, biblical names seem like talismans for me. Though I must admit that despite my grandfather's readings, and my own baptism and Christian upbringing, I was not a practicing Christian, perhaps not even a believer. And that is still the case: I must stress this from the outset so that nobody will be thinking, let alone hoping, that this is the story of a religious conversion.

I confess that when my boss said "Galilea," the word at first meant nothing to me, perhaps because the annoying way he pronounced the word robbed it of its power. And biblical names were usually relegated to our poorest neighborhoods--Belencito, Siloé, Nazaret--so I didnt give it a second thought.

Twenty minutes later I was in a taxi, heading for Galilea. The driver had never even heard of the place and had to radio for directions.

All I knew about angels was a prayer I used to recite as a child:

Sweet Guardian Angel

My heavenly guide

Hovering, night and day

Gently by my side.

My only contact with angels had been in grade school, at a procession on the thirteenth of May in honor of the Virgin Mary, and it had not turned out well. It so happened that one year, for being such a model student, my best friend, Marie Chris Cortés, had been chosen to be part of the Celestial Legion and had to wear an angel costume with a pair of very real-looking wings, which her mother had made for her out of real feathers. When I saw her, I laughed, and told her she looked more like a chicken than an angel, which was true.

--Translated by Dolores M. Koch

Textul de pe ultima copertă

Winner of Mexico's Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz Prize, and France's Prix France Culture, The Angel of Galilea introduces a refreshing new voice in Latin American literature to the English speaking audience.

Mona is a jaded reporter for a Colombian tabloid sent on assignment to investigate an angel sighting in one of Bogota's most devastated barrios, where she encounters a community torn apart by a passionate conflict over a beautiful man who walks the fine line between sanity and sainthood. For the people of Galilea, this mysterious and sensual "angel without a name" represents their hope amidst desperate circumstances; for Mona, he awakens her desire to love and gives her a reason to believe. When the barrio's priest leads a revolt against the fallen angel, Mona risks everything to protect him from the gang that threatens to destroy him.