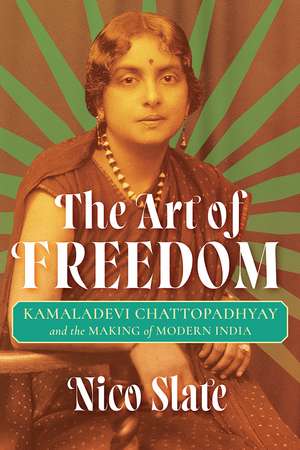

The Art of Freedom: Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay and the Making of Modern India

Autor Nico Slateen Limba Engleză Hardback – 30 apr 2024

Preț: 263.73 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 396

Preț estimativ în valută:

50.47€ • 52.39$ • 42.08£

50.47€ • 52.39$ • 42.08£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 03-17 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780822948209

ISBN-10: 0822948206

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 36 mm

Greutate: 0.64 kg

Editura: University of Pittsburgh Press

Colecția University of Pittsburgh Press

ISBN-10: 0822948206

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 36 mm

Greutate: 0.64 kg

Editura: University of Pittsburgh Press

Colecția University of Pittsburgh Press

Recenzii

"A groundbreaking exploration of the life and contributions of Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay."

—India West Journal

“In this magnificent biography, Nico Slate does full justice to the range and richness of her life and the depth and breadth of Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay’s legacy. His research is impressively thorough, his writing elegant and empathetic, his blending of biography and history seamless and deeply illuminating.”

—Ramachandra Guha, author of Gandhi: The Years That Changed the World

“This deeply researched book restores Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay to her rightful place in India’s history as a freedom fighter and nation builder. In a moving and original narrative, Nico Slate reveals the full emancipatory and participatory potential of Kamaladevi’s social reform activism and anticolonial politics.”

—Sana Aiyar, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

“A chiaroscuro of a life has been painted with stunning precision in Slate’s work. His scholarship and insight bring to vivid immediacy the light and shade of a gifted woman’s struggle for self-expression that coalesced with those of her country.”

—Gopalkrishna Gandhi, Ashoka University

“Nico Slate’s comprehensive and illuminating biography of the great Indian socialist and feminist Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya makes her life and achievements available to American audiences and as such is much appreciated.”

—Ellen Carol DuBois, University of California, Los Angeles

—India West Journal

“In this magnificent biography, Nico Slate does full justice to the range and richness of her life and the depth and breadth of Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay’s legacy. His research is impressively thorough, his writing elegant and empathetic, his blending of biography and history seamless and deeply illuminating.”

—Ramachandra Guha, author of Gandhi: The Years That Changed the World

“This deeply researched book restores Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay to her rightful place in India’s history as a freedom fighter and nation builder. In a moving and original narrative, Nico Slate reveals the full emancipatory and participatory potential of Kamaladevi’s social reform activism and anticolonial politics.”

—Sana Aiyar, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

“A chiaroscuro of a life has been painted with stunning precision in Slate’s work. His scholarship and insight bring to vivid immediacy the light and shade of a gifted woman’s struggle for self-expression that coalesced with those of her country.”

—Gopalkrishna Gandhi, Ashoka University

“Nico Slate’s comprehensive and illuminating biography of the great Indian socialist and feminist Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya makes her life and achievements available to American audiences and as such is much appreciated.”

—Ellen Carol DuBois, University of California, Los Angeles

Notă biografică

Nico Slate is professor in the Department of History at Carnegie Mellon University. His research examines struggles against racism and imperialism in the United States and India. His most recent book is Brothers: A Memoir of Love, Loss, and Race.

Extras

EXCERPT FROM THE INTRODUCTION TO THE ART OF FREEDOM

In the autumn of 1947, a forty-four-year-old woman visited a cavernous building in New Delhi known as the P-Block. The British Raj had just fallen. Two nations—India and Pakistan—had emerged from the wreckage of colonial rule. For generations, imperial authorities had stoked distrust between India’s largest religious communities. As the colonial state retreated, that distrust turned violent on a staggering scale. More than half a million people would die and more than ten million would flee their homes in one of the largest and bloodiest mass migrations in human history.

Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay arrived at the P-Block, the headquarters of the new Relief and Rehabilitation Secretariat, with a plan to resettle thousands of the refugees who had arrived in Delhi. Known throughout the subcontinent by her first name, Kamaladevi had acquired a considerable reputation for her work in the socialist and women’s movements and for having spent years in prison for her opposition to the British Raj. She worked closely with Mahatma Gandhi and with India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. Yet the officials of the Relief and Rehabilitation Secretariat did not respond to her request that land be allocated to the refugees. Undeterred by the bureaucracy’s indifference, she identified a patch of open terrain about twelve miles from the city and informed the authorities that if an appropriate alternative was not provided in the next three days, she would personally escort a group of refugees to claim the land. She hired trucks and worked with the refugees to gather all that was needed to build a temporary settlement. The night before they were to move, a letter arrived providing the land. Kamaladevi helped to organize a new city for refugees just outside of Delhi. Often described as a “model” community, the new town of Faridabad would house 30,000 people on some 1,500 acres. “From an unsightly settlement of ragged tents and squalid huts only a year and a half ago,” the New York Times declared in October 1951, “Faridabad has become a model of combined suburban and rural development with homes, jobs, schools and public health service for all.” With its own electric powerhouse, a 150-bed hospital, and a range of small, collaboratively run businesses—from a dairy farm to a button factory—Faridabad testified to the hope and hard work of thousands of uprooted people, the dedication of dozens of social workers, and the vision and determination of one indomitable woman.

Kamaladevi’s support for refugees was an act of empathy across many divides. Unlike most of the people she strove to empower, she had been born into wealth and status. Kamaladevi Dhareshwar entered the world on April 3, 1903, in Mangalore, a small city on the Arabian Sea in the present-day state of Karnataka. Her family belonged to one of the most affluent and educated communities in colonial India, the Chitrapur Saraswat Brahmins. Her life turned toward adversity when her father died without leaving a will. Most of the family’s wealth was inherited by a male relative, leaving Kamaladevi, her sisters, and her mother in a precarious position. At the age of eleven, Kamaladevi was married to an older boy from one of Mangalore’s wealthiest families. Only a year later, the boy died, leaving Kamaladevi a child widow at a time when widows were often expected to live austere and secluded lives. With support from her mother, Kamaladevi broke social custom by pursuing her own education and, at the age of sixteen, falling in love and remarrying across lines of language, region, and caste.

With her new husband, she sang and acted in plays and films at a time when “respectable” women rarely performed on stage or for a camera, and she traveled to England to pursue a degree in sociology at a time when few Indian women studied abroad. After returning to India to support Gandhi’s noncooperation movement, Kamaladevi became one of the first women to contest a legislative election in colonial India. She played a key role in the creation of the All India Women’s Conference (AIWC) and helped lead that organization as its first secretary. In 1930, when Gandhi launched a civil disobedience campaign while limiting the participation of women, Kamaladevi confronted him, helped to change his mind, and then herself became one of the first women arrested. She spent several years in prison, much of the time in solitary confinement.

Kamaladevi emerged from prison to find that her husband had fathered a child with another woman. She broke yet another taboo by divorcing him. In 1934, she helped found a socialist group within the Indian National Congress and emerged as one of the most influential leaders of the left wing of the freedom struggle. She was also among the most traveled. During the Second World War, she journeyed across the United States, Japan, and war-torn China before returning to India, where she was arrested yet again. After her release, she joined the Congress Working Committee—the party’s highest body—at one of the most crucial junctures in the history of the freedom struggle. Along with her socialist colleagues, she opposed the partition of India, a stance that brought her close to Gandhi toward the end of his life.

In the autumn of 1947, a forty-four-year-old woman visited a cavernous building in New Delhi known as the P-Block. The British Raj had just fallen. Two nations—India and Pakistan—had emerged from the wreckage of colonial rule. For generations, imperial authorities had stoked distrust between India’s largest religious communities. As the colonial state retreated, that distrust turned violent on a staggering scale. More than half a million people would die and more than ten million would flee their homes in one of the largest and bloodiest mass migrations in human history.

Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay arrived at the P-Block, the headquarters of the new Relief and Rehabilitation Secretariat, with a plan to resettle thousands of the refugees who had arrived in Delhi. Known throughout the subcontinent by her first name, Kamaladevi had acquired a considerable reputation for her work in the socialist and women’s movements and for having spent years in prison for her opposition to the British Raj. She worked closely with Mahatma Gandhi and with India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. Yet the officials of the Relief and Rehabilitation Secretariat did not respond to her request that land be allocated to the refugees. Undeterred by the bureaucracy’s indifference, she identified a patch of open terrain about twelve miles from the city and informed the authorities that if an appropriate alternative was not provided in the next three days, she would personally escort a group of refugees to claim the land. She hired trucks and worked with the refugees to gather all that was needed to build a temporary settlement. The night before they were to move, a letter arrived providing the land. Kamaladevi helped to organize a new city for refugees just outside of Delhi. Often described as a “model” community, the new town of Faridabad would house 30,000 people on some 1,500 acres. “From an unsightly settlement of ragged tents and squalid huts only a year and a half ago,” the New York Times declared in October 1951, “Faridabad has become a model of combined suburban and rural development with homes, jobs, schools and public health service for all.” With its own electric powerhouse, a 150-bed hospital, and a range of small, collaboratively run businesses—from a dairy farm to a button factory—Faridabad testified to the hope and hard work of thousands of uprooted people, the dedication of dozens of social workers, and the vision and determination of one indomitable woman.

Kamaladevi’s support for refugees was an act of empathy across many divides. Unlike most of the people she strove to empower, she had been born into wealth and status. Kamaladevi Dhareshwar entered the world on April 3, 1903, in Mangalore, a small city on the Arabian Sea in the present-day state of Karnataka. Her family belonged to one of the most affluent and educated communities in colonial India, the Chitrapur Saraswat Brahmins. Her life turned toward adversity when her father died without leaving a will. Most of the family’s wealth was inherited by a male relative, leaving Kamaladevi, her sisters, and her mother in a precarious position. At the age of eleven, Kamaladevi was married to an older boy from one of Mangalore’s wealthiest families. Only a year later, the boy died, leaving Kamaladevi a child widow at a time when widows were often expected to live austere and secluded lives. With support from her mother, Kamaladevi broke social custom by pursuing her own education and, at the age of sixteen, falling in love and remarrying across lines of language, region, and caste.

With her new husband, she sang and acted in plays and films at a time when “respectable” women rarely performed on stage or for a camera, and she traveled to England to pursue a degree in sociology at a time when few Indian women studied abroad. After returning to India to support Gandhi’s noncooperation movement, Kamaladevi became one of the first women to contest a legislative election in colonial India. She played a key role in the creation of the All India Women’s Conference (AIWC) and helped lead that organization as its first secretary. In 1930, when Gandhi launched a civil disobedience campaign while limiting the participation of women, Kamaladevi confronted him, helped to change his mind, and then herself became one of the first women arrested. She spent several years in prison, much of the time in solitary confinement.

Kamaladevi emerged from prison to find that her husband had fathered a child with another woman. She broke yet another taboo by divorcing him. In 1934, she helped found a socialist group within the Indian National Congress and emerged as one of the most influential leaders of the left wing of the freedom struggle. She was also among the most traveled. During the Second World War, she journeyed across the United States, Japan, and war-torn China before returning to India, where she was arrested yet again. After her release, she joined the Congress Working Committee—the party’s highest body—at one of the most crucial junctures in the history of the freedom struggle. Along with her socialist colleagues, she opposed the partition of India, a stance that brought her close to Gandhi toward the end of his life.