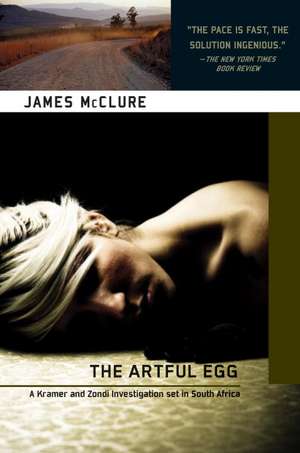

The Artful Egg: Kramer and Zondi Investigations Set in South Africa

Autor James McClureen Limba Engleză Paperback – 18 feb 2013

Preț: 96.66 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 145

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.50€ • 19.15$ • 15.64£

18.50€ • 19.15$ • 15.64£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781616952457

ISBN-10: 1616952458

Pagini: 316

Dimensiuni: 127 x 188 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Soho Crime

Seria Kramer and Zondi Investigations Set in South Africa

ISBN-10: 1616952458

Pagini: 316

Dimensiuni: 127 x 188 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Soho Crime

Seria Kramer and Zondi Investigations Set in South Africa

Notă biografică

James McClure (1939-2006) was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, where he worked as a photographer and then a teacher before becoming a crime reporter. He published eight wildly successful books in the Kramer and Zondi series during his lifetime and was the recipient of the CWA Silver and Gold Daggers.

Extras

Chapter 1

A hen is an egg’s way of making another egg.

This was the thought uppermost in the mind of Ramjut Pillay, Asiatic Postman 2nd Class, at the start of the horrific Tuesday morning that altered the course of his life. He tried to have an uppermost thought every morning, for fear of being lulled into intellectual stagnation by the sort of reading his work required of him:

Mrs. WM Truscott

4 Jan Smuts Close,

Morningside,

Trekkersburg,

Natal,

South Africa

Not that most envelopes, being mailed locally, had anything like as much on them, making this example—an air letter from Cincinnati—the workaday equivalent of War and Peace.

Not that there was ever any real need to read further than the first couple of lines anyway, because nothing reached his sorting-frame that hadn’t already been set aside for Morningside, but he prided himself on being conscientious.

Ramjut Pillay slipped Mrs. Truscott’s air letter through the slot in her front door, sidestepped her dachshund with nimble disdain, and continued on his way. There was nothing today for the Van der Plank family at number 6, and only a few bills and a holiday postcard for the Trenchards at number 8.

He no longer perused postcards; the sheer inanity of their scribbled messages was more than his rather remarkable mind could bear.

“So let us ponder more profoundly and afresh,” he murmured, as he opened the gate to 8 Jan Smuts Close, “the devilish cunning shown by the aforesaid egg, and its consequent effect upon the wretched fowl in question. . . .”

Ramjut Pillay invariably used the plural form when addressing himself, being exceedingly conscious of the fact that there was a lot more to him than met the eye—which, admittedly, wasn’t much.

Bespectacled, standing five-two-and-a-quarter, slightly bow-legged and as spare as a sparrow’s drumstick, he “reliably informed” his pen pals the world over that he was “wholly Gandhi-esque” in appearance, “save for a head of

truly healthy hair.” What he didn’t tell his pen pals was that people frequently looked right through him, just as though he wasn’t there, and that, as a child, his mother had kept losing him on buses, in shops, and at the Hindu temple down Harber Road.

Once, when he was about twelve years old, his father and mother, after a frantic search of the bottom end of town, had found him seated in the midst of the temple elders, under a sacred fig-tree. “Ramjut,” his mother had cried out, “don’t you know how worried your father and I have been? Just what are you up to, child, with these wise old men?” To which he had replied: “Eating figs.”

The front door to 8 Jan Smuts Close opened before he could

slip the mail through its letter-slot.

“I wondered if—” began blowsy Mrs. Trenchard, her green eyes darting to the mail in his right hand.

He knew what she was after. All last week it’d been the same, the constant hope against hope that her son had written to her from army camp. “You keep hearing these stories,” she had explained to him, “that they’re no sooner given their boots than they’re sent to fight in the bush in Namibia.” Indeed, her motherly anguish would once again have been pitiful to behold, were Ramjut Pillay paying the slightest attention to it.

Instead, he was slyly stealing a look at seventeen-year-old Suzie Trenchard—he’d delivered her recent birthday cards in their unsealed envelopes—who was languidly descending the staircase, engrossed in a glossy magazine. The white girl’s legs were bare all the way up to the frilly-edged panties she wore beneath a shortie nightie. What legs! Broad thighs, smooth knees, calves with a truly heavenly curve to them. The full

breasts were also quite exquisite, a pair of bobbing sweet melons which jutted the sheer fabric and gave it a delicate shake each step she took. Several split-seconds passed before he could reluctantly collect himself.

“You were wondering, madam?” said Ramjut Pillay, fanning the mail like a conjuror and suggesting she picked the postcard.

“Blast,” said Mrs. Trenchard, hardly glancing at it. “Is that the best you can do?”

“The picture is most pretty and informative,” Ramjut Pillay pointed out.

“Don’t be cheeky!” snapped Mrs. Trenchard. “What I want to know is, haven’t you anything else for me?”

There was really no need for her to be so rude, so he indulged a simple pleasure by handing over the bills one by one. Then, with a final forbidden glance at Suzie Trenchard, whose delectable bottom was giving a ripe jiggle as she disappeared down the passage towards the kitchen, he turned and went on his way.

“Suzie!” he heard Mrs. Trenchard shouting out, a moment before the front door was slammed shut. “Suzie, will you come downstairs this minute for your breakfast? And see you’re decent, do you hear? Don’t forget the servants.”

Two letters, an electricity bill, and a small packet of colour prints went sliding through on to the hall carpet of 10 Jan Smuts Close.

“A hen is an egg’s way of making. . . .”

But his uppermost thought had changed.

It was always so when Ramjut Pillay felt a stirring in his loins.

A condition, moreover, that tended to elevate his thoughts still

further, reminding him of his deep affinity with the Mahatma.

“Brahmacharya. . . .” he whispered reverently, not noticing

that he’d given 12 Jan Smuts Close the mail for numbers 14

and 16 as well, so great was his preoccupation at this moment

with Higher Things.

The brahmacharya experiments, as any devotee of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi knew full well, had entailed the Mahatma lying all night with naked young girls beside him, testing his will to abstain. Gandhi’s will had reportedly never failed him, and neither would Ramjut Pillay’s, he felt sure, given the opportunity to undergo a similar ordeal.

“There’s the rubbing,” he muttered to himself, hurrying on up the close. “The damnable rubbing. . . .”

The rub being quite simply that, try as he might, Ramjut Pillay had yet to find a young girl in Trekkersburg who was willing to lie naked beside him all night. Once, he had come very close to emulating the Mahatma, that was beyond dispute—although her

father still did not see it that way, and he had to make a two-block detour whenever he chanced to be in that part of town. And once, having decided that tender years might not be an absolute requirement of a brahmacharya experiment, he had attempted a

night with Sophia, a middle-aged Tamil lady well known for her accommodating disposition. That had worked very well for the first hour; and then, growing restless, Sophia had given a deep sigh before suddenly heaving herself on to him.

“I say,” called out old Major MacTaggart from the porch of 14 Jan Smuts Close, “dash it all, I was expecting a copy of the club minutes this morning. You weren’t just going to trot by, were you?”

“M-Major?”

“Big brown envelope.”

Ramjut Pillay seemed to remember a big brown envelope in his Jan Smuts Close bundle, but a quick check revealed that his memory, usually so perfect in every way, must have played a trick on him. “So sorry, Major,” he said, “no can do today.”

“Humph,” Major MacTaggart snorted unpleasantly. “I’ve my doubts about you as a post wallah, Pillay, serious doubts. Well, don’t just stand there looking holier-than-thou, you bandy old rascal—you’re late enough as it is.”

Seething with indignation, yet no better placed to protest than when Sophia had clapped a hand over his mouth before having her vigorous way with him, Ramjut Pillay continued on up Jan Smuts Close. By jingo, how the world took advantage of an avowed pacifist.

“A ruddy hen,” he said crossly, “is an egg’s—”

No good. He simply couldn’t be expected to concentrate, certainly not under these circumstances. Post wallah? What a damnable impudence! What a way to speak to a highly educated man, qualified ten times over in any number of things. Why, the principal of the Easiway Correspondence College, the world-famous Dr. Gideon de Bruin, was forever congratulating him on the variety of diplomas he continued to be awarded, ranging from Automotive Engineering (Theory Only) to Elementary Philosophy, Newspaper Cartooning and Conversational Afrikaans.

“That’s a pretty stamp,” remarked Miss Simson at 20 Jan Smuts Close, as she signed for a registered letter, “on that cream envelope, half-sticking out of your bag.”

Ramjut Pillay glanced down. Great heavens, he’d quite forgotten he had this to look forward to. “Yes, the new UK issue, madam,” he said, “and the first time I am ever seeing one.”

“So, are you going to ask them if you can have it?” said Miss Simson, smiling as she handed back his ballpoint pen. “To add to your collection?”

“Most assuredly,” Ramjut Pillay replied, nodding.

But it wasn’t until he had actually reached the top end of Jan Smuts Close that his mood changed properly, allowing him to appreciate again what a beautiful morning it was, and to anticipate to the full becoming the proud owner of such a fine example of British stamp design.

“Now, let us see. . . .” he said, pausing to take out the cream envelope and to rummage about for the rest of the mail for Woodhollow.

There was always quite a bit of it, the bulk coming from overseas and being addressed to Naomi Stride. Yes, just “Naomi Stride,” with no “Mrs” or “Miss” in front, which was because, she had explained to him, it was her “professional name,” whatever

that meant. Then, to complicate matters, she also received post for Mrs. Naomi Kennedy, for Mrs. N.G. Kennedy, and for Mrs. W.J. Kennedy, although nothing ever arrived for a Mr. Kennedy.

To the cream envelope Ramjut Pillay added six other personal letters, four business letters and a circular, then started up the long drive. Woodhollow, or 30 Jan Smuts Close as it really should have been known, wasn’t strictly speaking part of the cul-de-sac of modest middle-class bungalows at all, but stood well back, behind a screen of Scots firs up at the top end, facing away over a wooded valley. It always took a minute or two, in fact, before someone approaching on foot actually saw the house, so dense was the surrounding vegetation.

“Ah, such beauty,” sighed Ramjut Pillay, and inhaled again the heavy scent of the flowering shrubs on either side of him.

He pictured the lady coming to the door, his asking for the stamp most politely, and her agreeing as always, giving that throaty little laugh. Perhaps she would want to ask him more about preparing curries, which she did from time to time, and he would have a glass of chilled orange juice brought out to him by the servant.

Just then, there was a stirring in his loins, making him

wonder why on earth the problem of the brahmacharya experiments should return to bother him at such a time. Then, without warning, a truly shocking insight provided the answer to that, tempting him to think the unthinkable.

He gave in.

A hen is an egg’s way of making another egg.

This was the thought uppermost in the mind of Ramjut Pillay, Asiatic Postman 2nd Class, at the start of the horrific Tuesday morning that altered the course of his life. He tried to have an uppermost thought every morning, for fear of being lulled into intellectual stagnation by the sort of reading his work required of him:

Mrs. WM Truscott

4 Jan Smuts Close,

Morningside,

Trekkersburg,

Natal,

South Africa

Not that most envelopes, being mailed locally, had anything like as much on them, making this example—an air letter from Cincinnati—the workaday equivalent of War and Peace.

Not that there was ever any real need to read further than the first couple of lines anyway, because nothing reached his sorting-frame that hadn’t already been set aside for Morningside, but he prided himself on being conscientious.

Ramjut Pillay slipped Mrs. Truscott’s air letter through the slot in her front door, sidestepped her dachshund with nimble disdain, and continued on his way. There was nothing today for the Van der Plank family at number 6, and only a few bills and a holiday postcard for the Trenchards at number 8.

He no longer perused postcards; the sheer inanity of their scribbled messages was more than his rather remarkable mind could bear.

“So let us ponder more profoundly and afresh,” he murmured, as he opened the gate to 8 Jan Smuts Close, “the devilish cunning shown by the aforesaid egg, and its consequent effect upon the wretched fowl in question. . . .”

Ramjut Pillay invariably used the plural form when addressing himself, being exceedingly conscious of the fact that there was a lot more to him than met the eye—which, admittedly, wasn’t much.

Bespectacled, standing five-two-and-a-quarter, slightly bow-legged and as spare as a sparrow’s drumstick, he “reliably informed” his pen pals the world over that he was “wholly Gandhi-esque” in appearance, “save for a head of

truly healthy hair.” What he didn’t tell his pen pals was that people frequently looked right through him, just as though he wasn’t there, and that, as a child, his mother had kept losing him on buses, in shops, and at the Hindu temple down Harber Road.

Once, when he was about twelve years old, his father and mother, after a frantic search of the bottom end of town, had found him seated in the midst of the temple elders, under a sacred fig-tree. “Ramjut,” his mother had cried out, “don’t you know how worried your father and I have been? Just what are you up to, child, with these wise old men?” To which he had replied: “Eating figs.”

The front door to 8 Jan Smuts Close opened before he could

slip the mail through its letter-slot.

“I wondered if—” began blowsy Mrs. Trenchard, her green eyes darting to the mail in his right hand.

He knew what she was after. All last week it’d been the same, the constant hope against hope that her son had written to her from army camp. “You keep hearing these stories,” she had explained to him, “that they’re no sooner given their boots than they’re sent to fight in the bush in Namibia.” Indeed, her motherly anguish would once again have been pitiful to behold, were Ramjut Pillay paying the slightest attention to it.

Instead, he was slyly stealing a look at seventeen-year-old Suzie Trenchard—he’d delivered her recent birthday cards in their unsealed envelopes—who was languidly descending the staircase, engrossed in a glossy magazine. The white girl’s legs were bare all the way up to the frilly-edged panties she wore beneath a shortie nightie. What legs! Broad thighs, smooth knees, calves with a truly heavenly curve to them. The full

breasts were also quite exquisite, a pair of bobbing sweet melons which jutted the sheer fabric and gave it a delicate shake each step she took. Several split-seconds passed before he could reluctantly collect himself.

“You were wondering, madam?” said Ramjut Pillay, fanning the mail like a conjuror and suggesting she picked the postcard.

“Blast,” said Mrs. Trenchard, hardly glancing at it. “Is that the best you can do?”

“The picture is most pretty and informative,” Ramjut Pillay pointed out.

“Don’t be cheeky!” snapped Mrs. Trenchard. “What I want to know is, haven’t you anything else for me?”

There was really no need for her to be so rude, so he indulged a simple pleasure by handing over the bills one by one. Then, with a final forbidden glance at Suzie Trenchard, whose delectable bottom was giving a ripe jiggle as she disappeared down the passage towards the kitchen, he turned and went on his way.

“Suzie!” he heard Mrs. Trenchard shouting out, a moment before the front door was slammed shut. “Suzie, will you come downstairs this minute for your breakfast? And see you’re decent, do you hear? Don’t forget the servants.”

Two letters, an electricity bill, and a small packet of colour prints went sliding through on to the hall carpet of 10 Jan Smuts Close.

“A hen is an egg’s way of making. . . .”

But his uppermost thought had changed.

It was always so when Ramjut Pillay felt a stirring in his loins.

A condition, moreover, that tended to elevate his thoughts still

further, reminding him of his deep affinity with the Mahatma.

“Brahmacharya. . . .” he whispered reverently, not noticing

that he’d given 12 Jan Smuts Close the mail for numbers 14

and 16 as well, so great was his preoccupation at this moment

with Higher Things.

The brahmacharya experiments, as any devotee of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi knew full well, had entailed the Mahatma lying all night with naked young girls beside him, testing his will to abstain. Gandhi’s will had reportedly never failed him, and neither would Ramjut Pillay’s, he felt sure, given the opportunity to undergo a similar ordeal.

“There’s the rubbing,” he muttered to himself, hurrying on up the close. “The damnable rubbing. . . .”

The rub being quite simply that, try as he might, Ramjut Pillay had yet to find a young girl in Trekkersburg who was willing to lie naked beside him all night. Once, he had come very close to emulating the Mahatma, that was beyond dispute—although her

father still did not see it that way, and he had to make a two-block detour whenever he chanced to be in that part of town. And once, having decided that tender years might not be an absolute requirement of a brahmacharya experiment, he had attempted a

night with Sophia, a middle-aged Tamil lady well known for her accommodating disposition. That had worked very well for the first hour; and then, growing restless, Sophia had given a deep sigh before suddenly heaving herself on to him.

“I say,” called out old Major MacTaggart from the porch of 14 Jan Smuts Close, “dash it all, I was expecting a copy of the club minutes this morning. You weren’t just going to trot by, were you?”

“M-Major?”

“Big brown envelope.”

Ramjut Pillay seemed to remember a big brown envelope in his Jan Smuts Close bundle, but a quick check revealed that his memory, usually so perfect in every way, must have played a trick on him. “So sorry, Major,” he said, “no can do today.”

“Humph,” Major MacTaggart snorted unpleasantly. “I’ve my doubts about you as a post wallah, Pillay, serious doubts. Well, don’t just stand there looking holier-than-thou, you bandy old rascal—you’re late enough as it is.”

Seething with indignation, yet no better placed to protest than when Sophia had clapped a hand over his mouth before having her vigorous way with him, Ramjut Pillay continued on up Jan Smuts Close. By jingo, how the world took advantage of an avowed pacifist.

“A ruddy hen,” he said crossly, “is an egg’s—”

No good. He simply couldn’t be expected to concentrate, certainly not under these circumstances. Post wallah? What a damnable impudence! What a way to speak to a highly educated man, qualified ten times over in any number of things. Why, the principal of the Easiway Correspondence College, the world-famous Dr. Gideon de Bruin, was forever congratulating him on the variety of diplomas he continued to be awarded, ranging from Automotive Engineering (Theory Only) to Elementary Philosophy, Newspaper Cartooning and Conversational Afrikaans.

“That’s a pretty stamp,” remarked Miss Simson at 20 Jan Smuts Close, as she signed for a registered letter, “on that cream envelope, half-sticking out of your bag.”

Ramjut Pillay glanced down. Great heavens, he’d quite forgotten he had this to look forward to. “Yes, the new UK issue, madam,” he said, “and the first time I am ever seeing one.”

“So, are you going to ask them if you can have it?” said Miss Simson, smiling as she handed back his ballpoint pen. “To add to your collection?”

“Most assuredly,” Ramjut Pillay replied, nodding.

But it wasn’t until he had actually reached the top end of Jan Smuts Close that his mood changed properly, allowing him to appreciate again what a beautiful morning it was, and to anticipate to the full becoming the proud owner of such a fine example of British stamp design.

“Now, let us see. . . .” he said, pausing to take out the cream envelope and to rummage about for the rest of the mail for Woodhollow.

There was always quite a bit of it, the bulk coming from overseas and being addressed to Naomi Stride. Yes, just “Naomi Stride,” with no “Mrs” or “Miss” in front, which was because, she had explained to him, it was her “professional name,” whatever

that meant. Then, to complicate matters, she also received post for Mrs. Naomi Kennedy, for Mrs. N.G. Kennedy, and for Mrs. W.J. Kennedy, although nothing ever arrived for a Mr. Kennedy.

To the cream envelope Ramjut Pillay added six other personal letters, four business letters and a circular, then started up the long drive. Woodhollow, or 30 Jan Smuts Close as it really should have been known, wasn’t strictly speaking part of the cul-de-sac of modest middle-class bungalows at all, but stood well back, behind a screen of Scots firs up at the top end, facing away over a wooded valley. It always took a minute or two, in fact, before someone approaching on foot actually saw the house, so dense was the surrounding vegetation.

“Ah, such beauty,” sighed Ramjut Pillay, and inhaled again the heavy scent of the flowering shrubs on either side of him.

He pictured the lady coming to the door, his asking for the stamp most politely, and her agreeing as always, giving that throaty little laugh. Perhaps she would want to ask him more about preparing curries, which she did from time to time, and he would have a glass of chilled orange juice brought out to him by the servant.

Just then, there was a stirring in his loins, making him

wonder why on earth the problem of the brahmacharya experiments should return to bother him at such a time. Then, without warning, a truly shocking insight provided the answer to that, tempting him to think the unthinkable.

He gave in.

Recenzii

"The pace is fast, the solution ingenious. Above all, however, is the author's extraordinary naturalistic style. He is that rarity—a sensitive writer who can carry his point without forcing."—The New York Times Book Review

"McClure's stories ... have been noteworthy in equal measure for their poignant evocation of [South Africa], their perception of partnership, and their acute sense of sexual obsession."—Time Magazine

"[McClure is] a distinguished crime novelist who has created in his Afrikaner Tromp Kramer and Bantu Sergeant Zondi two detectives who are as far from stereotypes as any in the genre."—P. D. James

"McClure's stories ... have been noteworthy in equal measure for their poignant evocation of [South Africa], their perception of partnership, and their acute sense of sexual obsession."—Time Magazine

"[McClure is] a distinguished crime novelist who has created in his Afrikaner Tromp Kramer and Bantu Sergeant Zondi two detectives who are as far from stereotypes as any in the genre."—P. D. James