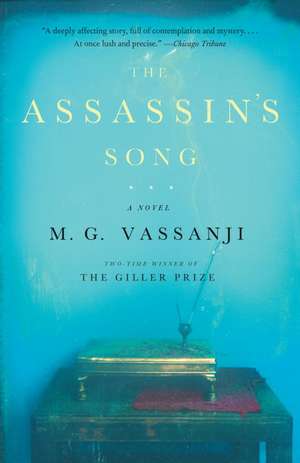

The Assassin's Song

Autor M. G. Vassanjien Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2008

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Scotiabank Giller Prize (2007)

Preț: 82.70 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 124

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.82€ • 16.56$ • 13.17£

15.82€ • 16.56$ • 13.17£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400076574

ISBN-10: 1400076579

Pagini: 338

Dimensiuni: 134 x 202 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 1400076579

Pagini: 338

Dimensiuni: 134 x 202 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

M. G. Vassanji was born in Kenya and raised in Tanzania. Before coming to Canada in 1978, he attended M.I.T. and the University of Pennsylvania, and later was writer in residence at the International Writing Program of the University of Iowa. Vassanji is the author of four acclaimed novels: The Gunny Sack, which won a regional Commonwealth Prize; No New Land; The Book of Secrets, which won the very first Giller Prize; and Amriika. He lives in Toronto with his wife and two sons.

Extras

Chapter 1

Postmaster Flat, Shimla. April 14, 2002.

After the calamity, a beginning.

One night my father took me out for a stroll. This was a rare treat, for he was a reticent man, a great and divine presence in our village who hardly ever ventured out. But it was my birthday. And so my heart was full to bursting with his tall, looming presence beside me. We walked along the highway away from the village, and when we had gone sufficiently far, to where it was utterly quiet and dark, Bapu-ji stopped and stared momentarily at our broken, grey road blurring ahead into the night, then slowly turned around to go back. He looked up at the sky; I did likewise. “Look, Karsan,” said Bapu-ji. He pointed out the bright planets overhead, the speckle that was the North Star, at the constellations connected tenuously by their invisible threads. “When I was young,” he said, “I wished only to study the stars...But that was a long time ago, and a different world...

“But what lies above the stars?” he asked, after the pause, his voice rising a bare nuance above my head. “That is the important question I had to learn. What lies beyond the sky? What do you see when you remove this dark speckled blanket covering our heads? Nothing? But what is nothing?”

I was eleven years old that day. And my father had laid bare for me the essential condition of human existence.

I gaped with my child’s eyes at the blackness above my head, imagined it as a dark blanket dotted with little stars, imagined with a shiver what might lie beyond if you suddenly flung this drapery aside. Loneliness, big and terrifying enough to make you want to weep alone in the dark.

We slowly started on our way back home.

“There is no nothing,” Bapu-ji continued, as if to assuage my fears, his tremulous voice cutting like a saw the layers of darkness before us, “when you realize that everything is in the One...”

My father was the Saheb—the lord and keeper—of Pirbaag, the Shrine of the Wanderer, in our village of Haripir, as was his father before him, as were all our ancestors for many centuries. People came to him for guidance, they put their lives in his hands, they bowed to him with reverence.

As we walked back together towards the few modest lights of Haripir, father and first son, a certain fear, a heaviness of the heart came over me. It never left me, even when I was far away in a world of my own making. But at that time, although I had long suspected it, had received hints of it, I knew for certain that I was the gaadi-varas, the successor and avatar to come at Pirbaag after my father.

I often wished my distinction would simply go away, that I would wake up one morning and it wouldn’t be there. I did not want to be God, or His trustee, or His avatar—the distinctions often blurred in the realm of the mystical that was my inheritance. Growing up in the village all I wanted to be was ordinary, my ambition, like that of many another boy, to play cricket and break the world batting record for my country. But I had been chosen.

When we returned home, instead of taking the direct path from the roadside gate to our house, which lay straight ahead across an empty yard, my father took me by the separate doorway on our left into the walled compound that was the shrine. This was Pirbaag: calm and cold as infinity. The night air suffused with a faint glow, and an even fainter trace of rose, all around us the raised graves of the saints and sufis of the past, and our ancestors, and others deserving respect and prayers. They were large and small, these graves, ancient and recent, some well tended and heaped with flowers and coloured cloth, others lying forlorn at the fringes among the thorns, neglected and anonymous. This hallowed ground was our trust; we looked after it for people of any creed from any place to come to be blessed and comforted.

Overlooking everything here, towards the farther side of the compound was the grand mausoleum of a thirteenth-century mystic, a sufi called Nur Fazal, known to us belovedly as Pir Bawa and to the world around us as Mussafar Shah, the Wanderer. One day, centuries ago, he came wandering into our land, Gujarat, like a meteor from beyond, and settled here. He became our guide and guru, he showed us the path to liberation from the bonds of temporal existence. Little was known and few really cared about his historical identity: where exactly he came from, who he was, the name of his people. His mother tongue was Persian, perhaps, but he gave us his teachings in the form of songs he composed in our own language, Gujarati.

He was sometimes called the Gardener, because he loved gardens, and he tended his followers like seedlings. He had yet another, curious name, Kaatil, or Killer, which thrilled us children no end. But its provenance was less exciting: he had a piercing look, it was said, sharp as an arrow, and an intellect keen as the blade of a rapier, using which he won many debates in the great courts of the kings.

I would come to believe that my grandfather had an idea of his identity, and my Bapu-ji too, and that in due course when I took on the mantle I too would learn the secret of the sufi.

But now the shrine lies in ruins, a victim of the violence that so gripped our state recently, an orgy of murder and destruction of the kind we euphemistically call “riots.” Only the rats visit the sufi now, to root among the ruins. My father is dead and so is my mother. And my brother militantly calls himself a Muslim and is wanted for questioning regarding a horrific crime. Perhaps such an end was a foregone conclusion—Kali Yuga, the Dark Age, was upon us, as Bapu-ji always warned, quoting our saints and the scriptures: an age when gold became black iron, the ruler betrayed his trust, justice threw aside its blindfold, and the son defied his father. Though Bapu-ji did not expect this last of his favoured first son.

The thought will always remain with me: was my betrayal a part of the prophecy; or could I have averted the calamity that befell us? My logical mind—our first casualty, according to Bapu-ji—has long refused to put faith in such prophecies. I believe simply that my sin, my abandonment and defiance of my inheritance, was a sign of the times. Call the times Kali Yuga if you like—and we can quibble over the question of whether there ever was a Golden Age in which all was good and the sacrificed horse stood up whole after being ritually quartered and eaten. Whatever the case, I was expected to rise above the dark times and be the new saviour.

This role, which I once spurned, I must now assume. I, the last lord of the shrine of Pirbaag, must pick up the pieces of my trust and tell its story—and defy the destroyers, those who in their hatred would not only erase us from the ground of our forefathers but also attempt to write themselves upon it, make ink from our ashes.

The story begins with the arrival in Gujarat of the sufi Nur Fazal. He was our origin, the word and the song, our mother and father and our lover. Forgive me if I must sing to you. The past was told to me always accompanied by song; and now, when memory falters and the pictures in the mind fade and tear and all seems lost, it is the song that prevails.

Chapter 2

From western lands to glorious Patan

He came, of moon visage and arrow eyes.

To the lake of a thousand gods he came

Pranam! sang the gods, thirty-three crores of them.

Saraswati, Vishnu, Brahma bade him inside

Shiva Nataraja brought him water to drink.

The god himself washed this Wanderer’s feet

How could beloved Patan’s sorcerers compete?

You are the true man, said the king, your wisdom great

Be our guest, show us the truth.

c. a.d. 1260.

The arrival of the sufi; the contest of magics.

It used to be said of Patan Anularra in the Gujarat kingdom of medieval India that there was not a city within a thousand miles to match its splendour, not a ruler in that vast region not subject to its king. The wealth of its many bazaars came from all corners of the world through the great ports of Cambay and Broach, and from all across Hindustan over land. It boasted the foremost linguists, mathematicians, philosophers, and poets; thousands of students came to study at the feet of its teachers. When the great scholar and priest Hemachandra completed his grammar of Sanskrit that was also a history of the land, it was launched in a grand procession through the avenues of the city, its pages carried on the backs of elephants and trailed by all the learned men. Great intellectual debates took place in the palace, but with dire consequences for the losers, who often had to seek a new city and another patron. In recent times, though, an uneasy air had come to hang over this capital, riding on rumours of doom and catastrophe that travelled with increasing frequency from the north.

Into this once glorious but now a little nervous city there arrived one morning with the dawn a mysterious visitor. He was a man of such a striking visage that on the highways which he had recently travelled men would avert their faces when they crossed his path, then turned to stare long and hard at his back as he hastened on southward. He was medium in stature and extremely fair; he had an emaciated face with a small pointed goatee, his eyes were green; and he wore the robe and turban of a sufi. His name he gave as Nur Fazal, of no fixed abode. He entered the city’s northern gate with a merchant caravan and was duly noted by his attire and language as a wandering Muslim mendicant and scholar originally from Afghanistan or Persia, and possibly a spy of the powerful sultanate of Delhi. Once inside, he put himself up at a small inn near the coppersmiths’ market frequented by the lesser of the foreign merchants and travellers. Soon afterwards, one afternoon, in the company of a local follower, he proceeded to the citadel of the raja, Vishal Dev. The time for the raja’s daily audience with the public was in the morning, but somehow the sufi, unseen at the gate—such were his powers—gained entrance and made his appearance inside.

From the Hardcover edition.

Postmaster Flat, Shimla. April 14, 2002.

After the calamity, a beginning.

One night my father took me out for a stroll. This was a rare treat, for he was a reticent man, a great and divine presence in our village who hardly ever ventured out. But it was my birthday. And so my heart was full to bursting with his tall, looming presence beside me. We walked along the highway away from the village, and when we had gone sufficiently far, to where it was utterly quiet and dark, Bapu-ji stopped and stared momentarily at our broken, grey road blurring ahead into the night, then slowly turned around to go back. He looked up at the sky; I did likewise. “Look, Karsan,” said Bapu-ji. He pointed out the bright planets overhead, the speckle that was the North Star, at the constellations connected tenuously by their invisible threads. “When I was young,” he said, “I wished only to study the stars...But that was a long time ago, and a different world...

“But what lies above the stars?” he asked, after the pause, his voice rising a bare nuance above my head. “That is the important question I had to learn. What lies beyond the sky? What do you see when you remove this dark speckled blanket covering our heads? Nothing? But what is nothing?”

I was eleven years old that day. And my father had laid bare for me the essential condition of human existence.

I gaped with my child’s eyes at the blackness above my head, imagined it as a dark blanket dotted with little stars, imagined with a shiver what might lie beyond if you suddenly flung this drapery aside. Loneliness, big and terrifying enough to make you want to weep alone in the dark.

We slowly started on our way back home.

“There is no nothing,” Bapu-ji continued, as if to assuage my fears, his tremulous voice cutting like a saw the layers of darkness before us, “when you realize that everything is in the One...”

My father was the Saheb—the lord and keeper—of Pirbaag, the Shrine of the Wanderer, in our village of Haripir, as was his father before him, as were all our ancestors for many centuries. People came to him for guidance, they put their lives in his hands, they bowed to him with reverence.

As we walked back together towards the few modest lights of Haripir, father and first son, a certain fear, a heaviness of the heart came over me. It never left me, even when I was far away in a world of my own making. But at that time, although I had long suspected it, had received hints of it, I knew for certain that I was the gaadi-varas, the successor and avatar to come at Pirbaag after my father.

I often wished my distinction would simply go away, that I would wake up one morning and it wouldn’t be there. I did not want to be God, or His trustee, or His avatar—the distinctions often blurred in the realm of the mystical that was my inheritance. Growing up in the village all I wanted to be was ordinary, my ambition, like that of many another boy, to play cricket and break the world batting record for my country. But I had been chosen.

When we returned home, instead of taking the direct path from the roadside gate to our house, which lay straight ahead across an empty yard, my father took me by the separate doorway on our left into the walled compound that was the shrine. This was Pirbaag: calm and cold as infinity. The night air suffused with a faint glow, and an even fainter trace of rose, all around us the raised graves of the saints and sufis of the past, and our ancestors, and others deserving respect and prayers. They were large and small, these graves, ancient and recent, some well tended and heaped with flowers and coloured cloth, others lying forlorn at the fringes among the thorns, neglected and anonymous. This hallowed ground was our trust; we looked after it for people of any creed from any place to come to be blessed and comforted.

Overlooking everything here, towards the farther side of the compound was the grand mausoleum of a thirteenth-century mystic, a sufi called Nur Fazal, known to us belovedly as Pir Bawa and to the world around us as Mussafar Shah, the Wanderer. One day, centuries ago, he came wandering into our land, Gujarat, like a meteor from beyond, and settled here. He became our guide and guru, he showed us the path to liberation from the bonds of temporal existence. Little was known and few really cared about his historical identity: where exactly he came from, who he was, the name of his people. His mother tongue was Persian, perhaps, but he gave us his teachings in the form of songs he composed in our own language, Gujarati.

He was sometimes called the Gardener, because he loved gardens, and he tended his followers like seedlings. He had yet another, curious name, Kaatil, or Killer, which thrilled us children no end. But its provenance was less exciting: he had a piercing look, it was said, sharp as an arrow, and an intellect keen as the blade of a rapier, using which he won many debates in the great courts of the kings.

I would come to believe that my grandfather had an idea of his identity, and my Bapu-ji too, and that in due course when I took on the mantle I too would learn the secret of the sufi.

But now the shrine lies in ruins, a victim of the violence that so gripped our state recently, an orgy of murder and destruction of the kind we euphemistically call “riots.” Only the rats visit the sufi now, to root among the ruins. My father is dead and so is my mother. And my brother militantly calls himself a Muslim and is wanted for questioning regarding a horrific crime. Perhaps such an end was a foregone conclusion—Kali Yuga, the Dark Age, was upon us, as Bapu-ji always warned, quoting our saints and the scriptures: an age when gold became black iron, the ruler betrayed his trust, justice threw aside its blindfold, and the son defied his father. Though Bapu-ji did not expect this last of his favoured first son.

The thought will always remain with me: was my betrayal a part of the prophecy; or could I have averted the calamity that befell us? My logical mind—our first casualty, according to Bapu-ji—has long refused to put faith in such prophecies. I believe simply that my sin, my abandonment and defiance of my inheritance, was a sign of the times. Call the times Kali Yuga if you like—and we can quibble over the question of whether there ever was a Golden Age in which all was good and the sacrificed horse stood up whole after being ritually quartered and eaten. Whatever the case, I was expected to rise above the dark times and be the new saviour.

This role, which I once spurned, I must now assume. I, the last lord of the shrine of Pirbaag, must pick up the pieces of my trust and tell its story—and defy the destroyers, those who in their hatred would not only erase us from the ground of our forefathers but also attempt to write themselves upon it, make ink from our ashes.

The story begins with the arrival in Gujarat of the sufi Nur Fazal. He was our origin, the word and the song, our mother and father and our lover. Forgive me if I must sing to you. The past was told to me always accompanied by song; and now, when memory falters and the pictures in the mind fade and tear and all seems lost, it is the song that prevails.

Chapter 2

From western lands to glorious Patan

He came, of moon visage and arrow eyes.

To the lake of a thousand gods he came

Pranam! sang the gods, thirty-three crores of them.

Saraswati, Vishnu, Brahma bade him inside

Shiva Nataraja brought him water to drink.

The god himself washed this Wanderer’s feet

How could beloved Patan’s sorcerers compete?

You are the true man, said the king, your wisdom great

Be our guest, show us the truth.

c. a.d. 1260.

The arrival of the sufi; the contest of magics.

It used to be said of Patan Anularra in the Gujarat kingdom of medieval India that there was not a city within a thousand miles to match its splendour, not a ruler in that vast region not subject to its king. The wealth of its many bazaars came from all corners of the world through the great ports of Cambay and Broach, and from all across Hindustan over land. It boasted the foremost linguists, mathematicians, philosophers, and poets; thousands of students came to study at the feet of its teachers. When the great scholar and priest Hemachandra completed his grammar of Sanskrit that was also a history of the land, it was launched in a grand procession through the avenues of the city, its pages carried on the backs of elephants and trailed by all the learned men. Great intellectual debates took place in the palace, but with dire consequences for the losers, who often had to seek a new city and another patron. In recent times, though, an uneasy air had come to hang over this capital, riding on rumours of doom and catastrophe that travelled with increasing frequency from the north.

Into this once glorious but now a little nervous city there arrived one morning with the dawn a mysterious visitor. He was a man of such a striking visage that on the highways which he had recently travelled men would avert their faces when they crossed his path, then turned to stare long and hard at his back as he hastened on southward. He was medium in stature and extremely fair; he had an emaciated face with a small pointed goatee, his eyes were green; and he wore the robe and turban of a sufi. His name he gave as Nur Fazal, of no fixed abode. He entered the city’s northern gate with a merchant caravan and was duly noted by his attire and language as a wandering Muslim mendicant and scholar originally from Afghanistan or Persia, and possibly a spy of the powerful sultanate of Delhi. Once inside, he put himself up at a small inn near the coppersmiths’ market frequented by the lesser of the foreign merchants and travellers. Soon afterwards, one afternoon, in the company of a local follower, he proceeded to the citadel of the raja, Vishal Dev. The time for the raja’s daily audience with the public was in the morning, but somehow the sufi, unseen at the gate—such were his powers—gained entrance and made his appearance inside.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“A deeply affecting story, full of contemplation and mystery. . . . At once lush and precise.”

—Chicago Tribune

“Thought-provoking and satisfying. . . . There are echoes of Rohinton Mistry, of V. S. Naipaul, of Salman Rushdie. But the lyricism of Karsan's contemplations, the careful evocation of place, the writer's obvious warmth for his characters, the sense of compassion layered into the story—these are all Vassanji's.”

—The Washington Post Book World

“A resplendent novel. . . .Vassanji eloquently details the sufferings of Karsan's family as the price of his individual freedom.”

—The New Yorker

“Moving. . . . A complex, multifaceted drama, one that interweaves history, religion and politics with a vibrant personal story.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

—Chicago Tribune

“Thought-provoking and satisfying. . . . There are echoes of Rohinton Mistry, of V. S. Naipaul, of Salman Rushdie. But the lyricism of Karsan's contemplations, the careful evocation of place, the writer's obvious warmth for his characters, the sense of compassion layered into the story—these are all Vassanji's.”

—The Washington Post Book World

“A resplendent novel. . . .Vassanji eloquently details the sufferings of Karsan's family as the price of his individual freedom.”

—The New Yorker

“Moving. . . . A complex, multifaceted drama, one that interweaves history, religion and politics with a vibrant personal story.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

Premii

- Scotiabank Giller Prize Nominee, 2007