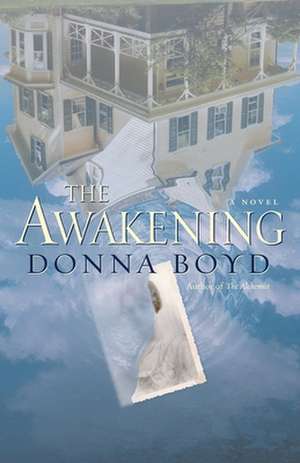

The Awakening

Autor Donna Boyden Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2003 – vârsta de la 14 până la 18 ani

Preț: 87.84 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 132

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.81€ • 17.44$ • 14.05£

16.81€ • 17.44$ • 14.05£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 februarie-10 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345462350

ISBN-10: 0345462351

Pagini: 202

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0345462351

Pagini: 202

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Extras

One

If a human being is the sum total of all her thoughts, memories, and experiences, then I was, for some indeterminate period of time, nothing. I did not exist. I hovered on the edge of consciousness like a breath waiting to be drawn in, a dream not quite formed into images, almost alive and not quite dead. It was not a particularly disagreeable state. Those who know nothing want for nothing, and it was good, for a time, simply not to care.

And then I began to awaken.

My memories of those first days are blurred and tossed together like fruit spilled from a basket; some moments, the brightest in color, stand out in particular; others are lost altogether; none are in the correct order. My eyes, so long unused to seeing, struggled to separate amorphous clouds of light into faces and objects, and did not always succeed. My ears could not quite distinguish one sound from another, and the background noise formed a rather soothing hum of almost musical cadence.

I whispered the customary words, surprised at how hollow and faraway my own voice sounded. “Where am I?”

A face floated into view, familiar, kind. But I could not say I recognized it.

“Don’t you remember?”

I sensed a disappointment when I did not answer, although the voice was carefully neutral. “Try to remember. You’ve been awake before. You’ve asked the question before. Try to remember what happened.”

But the gentle winds of void were beckoning to me again, and remembering seemed entirely too much trouble. I whispered, “I want to go home” just before I drifted away again.

And so it was, the same scene repeated over again, I can’t say how many times. I would awake, I would question; I would sleep, I would forget. But gradually, it seemed, I stayed awake longer, I forgot less. Memories drifted through my dreamlessness like dandelion fluff on a summer breeze.

A house with a green shutter that banged in the wind. A garden and a stone frog covered in moss. The smell of baking bread. A starched doily on a cherry table. Rain on the roof. A child’s voice.

Scraps of a life, bits of a woman. Particles of chaff, harmless and pretty as they danced in the sun, drifting closer and closer until I could see they weren’t chaff at all but floating moths with gossamer wings; no, not moths and not floating, but buzzing insects, darting and daring, irritating me, teasing and stinging and drawing me back to a place I didn’t want to be.

I opened my eyes to the hurtful light. I kept them open. And this time I asked a different question. “What’s wrong with me?”

The face was back, kind and concerned. A male face, familiar. That’s all I can tell you about it. “What can you remember?” he asked.

“What’s wrong with me?” I repeated, more forcefully now. “You can tell me. My husband is a doctor.”

Ah, that I should know that. It was a milestone, and I recognized the fact as well as he did.

“You’ve suffered a severe trauma,” he said gently. “There was a great deal of damage, I’m afraid, to your cognitive functions, and most particularly to your memory. We’ve all been very worried.”

A vague uneasiness crept through me, like beetles crawling on my skin. This time I couldn’t make it go away by slipping back into the nothing place. “How long?”

His eyes were sad and guarded. “A long time.”

Too long. I knew it in my bones. Too terrifyingly long. “Months?”

Silence pulsed like a heart, muffled and strained, whispered like a wind gathering force in the distance, fading, swelling. There were no words, no answers, but I found I did not need them. He just looked at me with those sad eyes, and certainty was like a cold, dark ribbon twining around my soul. I knew.

Too long.

“Who are you?”

This time it was I who asked the question, as we strolled some days or weeks later in the garden of what I had come to understand was the sanitarium where I had been admitted after the accident. I continued to be baffled by the indefinite control I possessed over my body, as though limbs, muscles, and responsive nerves had also been afflicted with spotty memory loss. Sometimes I strolled, sometimes I stumbled; sometimes I glided, sometimes I could not move at all no matter how hard I tried. I might reach for something and grasp only air. I might desperately want to reach for something, and be unable to move at all. The sweet-faced nurses and therapists assured me this all was normal, and that I was making a remarkable recovery. Perhaps. In truth, the challenges of learning to motivate through my environment, of envisioning an action and then performing it, seemed but minor inconveniences to me. I was far more concerned with what had been lost inside my mind.

Scraps of understanding were returning to me, though in no particular order and without a great deal of meaning. I knew, for example, that it had been an accident that was responsible for my injuries, but I did not know what kind of accident, nor how extensive those injuries were. I remembered the terror of that moment, the violence and suddenness of it, and even, to some startling extent, the pain. But I could remember no details.

I knew I was in a sanitarium, although I did not know how I knew it, and I did not know where, nor for how long. I did not know my age or my name or my station in life, nor what I looked like nor who were my friends nor who was my family. No one came to visit me. Had they all forgotten me? Or had there never been anyone at all who cared? Did I play the piano or like to dance? Who were my favorite authors? How did I like to pass the time on a lazy summer day? What kind of life had I had that I could leave it so easily and forget it entirely?

Sometimes questions like these consumed me with a feverish intensity; other times I didn’t care at all. Sometimes answers would come to me, as surprising as a suddenly popped balloon, with no warning whatsoever. Most of the time there were only questions.

The attendants at this place whose name I did not know were of precious little help. It was against policy, they said, to supply any answers about a resident’s past. It was very important that everything I learned be the result of spontaneous recollection; only in this way could my recovery be considered permanent and genuine.

So I had learned to mask my questions in innocuous forms, like “Who are you?” and to hoard every scrap of information that was returned to me against that time when I might have enough pieces of the puzzle to begin to put together a shape.

He said, with a firm and reassuring smile, “I am the person who is going to help you get better. You can call me Michael.”

“You’re a doctor.” A statement of the obvious. “I’m not comfortable calling you by your Christian name. It seems disrespectful.”

“It’s not, I assure you.”

We were in the garden because I longed so for the scent of clean air and the touch of the sun, for the lush ripeness of growing things and fecund earth. But the experience so far had been less than satisfactory. The colors seemed muted some- how, the greens flat and the yellows brown. The flowers had no scent. The light did not warm.

I knew there were medications that could dull the senses. But I was terrified by the thought that this muffling, foggy veil that seemed to have twined itself around my brain like spiderwebs on a dewy morning was nothing that could be induced by an injection or erased with a pill. The damage might be permanent. I might never again hear the trill of a chickadee in all its subtle nuances, or smell the perfume of spring grass, or gasp with delight over the shadow a butterfly cast on a stone path in late-summer light. The possibility filled me with such dread that I could not even ask for the truth of it.

I said, “My husband was a doctor, you know.”

“Yes, I know.”

“He was a brilliant man.”

We walked through the still and colorless garden with its soft, cool light and its pale flowers. I felt the comfort of Michael’s presence beside me, but it seemed a small thing, floating alone in a great hollow universe. I said softly, “He’s dead, isn’t he?”

“Yes.” Without hesitation, without apology. It was as though he were observing that the sky is blue, or remarking how lovely the forsythia was this year. Yes.

It was not so much sorrow that filled me, but a swelling sense of loss, a wave that crested and broke and was lost again in the sea of my despair. I wanted to weep, but could not find the tears. And I was shamed by the almost certain knowledge that, if I did cry, it would not be for the man whose face I could not remember, but for myself. He was dead. I think I had always known that.

I said, “It was the same accident that took my memory. There were no survivors.” Odd, how I simply said that, and knew it was true. Something else I must have always known.

We walked for a long time in empty silence. I said, “I’m all alone.”

“Of course you’re not. Everyone here wants to help you.”

“But they can’t, can they?” Now I turned and looked directly into the kind face of this man I did not know, but who was the only familiar thing in a world of void. “No one can help me. I think I must have read about places like these, people like me. No one ever gets better. No one ever goes home.”

“That’s not true. You’re going to get better.”

“Then help me!” I cried. “Tell me what happened to me, tell me what I’ve lost, tell me how he died! Tell me where I am and where I came from and what I have to do to get my memory back! Tell me who I am!”

If a human being is the sum total of all her thoughts, memories, and experiences, then I was, for some indeterminate period of time, nothing. I did not exist. I hovered on the edge of consciousness like a breath waiting to be drawn in, a dream not quite formed into images, almost alive and not quite dead. It was not a particularly disagreeable state. Those who know nothing want for nothing, and it was good, for a time, simply not to care.

And then I began to awaken.

My memories of those first days are blurred and tossed together like fruit spilled from a basket; some moments, the brightest in color, stand out in particular; others are lost altogether; none are in the correct order. My eyes, so long unused to seeing, struggled to separate amorphous clouds of light into faces and objects, and did not always succeed. My ears could not quite distinguish one sound from another, and the background noise formed a rather soothing hum of almost musical cadence.

I whispered the customary words, surprised at how hollow and faraway my own voice sounded. “Where am I?”

A face floated into view, familiar, kind. But I could not say I recognized it.

“Don’t you remember?”

I sensed a disappointment when I did not answer, although the voice was carefully neutral. “Try to remember. You’ve been awake before. You’ve asked the question before. Try to remember what happened.”

But the gentle winds of void were beckoning to me again, and remembering seemed entirely too much trouble. I whispered, “I want to go home” just before I drifted away again.

And so it was, the same scene repeated over again, I can’t say how many times. I would awake, I would question; I would sleep, I would forget. But gradually, it seemed, I stayed awake longer, I forgot less. Memories drifted through my dreamlessness like dandelion fluff on a summer breeze.

A house with a green shutter that banged in the wind. A garden and a stone frog covered in moss. The smell of baking bread. A starched doily on a cherry table. Rain on the roof. A child’s voice.

Scraps of a life, bits of a woman. Particles of chaff, harmless and pretty as they danced in the sun, drifting closer and closer until I could see they weren’t chaff at all but floating moths with gossamer wings; no, not moths and not floating, but buzzing insects, darting and daring, irritating me, teasing and stinging and drawing me back to a place I didn’t want to be.

I opened my eyes to the hurtful light. I kept them open. And this time I asked a different question. “What’s wrong with me?”

The face was back, kind and concerned. A male face, familiar. That’s all I can tell you about it. “What can you remember?” he asked.

“What’s wrong with me?” I repeated, more forcefully now. “You can tell me. My husband is a doctor.”

Ah, that I should know that. It was a milestone, and I recognized the fact as well as he did.

“You’ve suffered a severe trauma,” he said gently. “There was a great deal of damage, I’m afraid, to your cognitive functions, and most particularly to your memory. We’ve all been very worried.”

A vague uneasiness crept through me, like beetles crawling on my skin. This time I couldn’t make it go away by slipping back into the nothing place. “How long?”

His eyes were sad and guarded. “A long time.”

Too long. I knew it in my bones. Too terrifyingly long. “Months?”

Silence pulsed like a heart, muffled and strained, whispered like a wind gathering force in the distance, fading, swelling. There were no words, no answers, but I found I did not need them. He just looked at me with those sad eyes, and certainty was like a cold, dark ribbon twining around my soul. I knew.

Too long.

“Who are you?”

This time it was I who asked the question, as we strolled some days or weeks later in the garden of what I had come to understand was the sanitarium where I had been admitted after the accident. I continued to be baffled by the indefinite control I possessed over my body, as though limbs, muscles, and responsive nerves had also been afflicted with spotty memory loss. Sometimes I strolled, sometimes I stumbled; sometimes I glided, sometimes I could not move at all no matter how hard I tried. I might reach for something and grasp only air. I might desperately want to reach for something, and be unable to move at all. The sweet-faced nurses and therapists assured me this all was normal, and that I was making a remarkable recovery. Perhaps. In truth, the challenges of learning to motivate through my environment, of envisioning an action and then performing it, seemed but minor inconveniences to me. I was far more concerned with what had been lost inside my mind.

Scraps of understanding were returning to me, though in no particular order and without a great deal of meaning. I knew, for example, that it had been an accident that was responsible for my injuries, but I did not know what kind of accident, nor how extensive those injuries were. I remembered the terror of that moment, the violence and suddenness of it, and even, to some startling extent, the pain. But I could remember no details.

I knew I was in a sanitarium, although I did not know how I knew it, and I did not know where, nor for how long. I did not know my age or my name or my station in life, nor what I looked like nor who were my friends nor who was my family. No one came to visit me. Had they all forgotten me? Or had there never been anyone at all who cared? Did I play the piano or like to dance? Who were my favorite authors? How did I like to pass the time on a lazy summer day? What kind of life had I had that I could leave it so easily and forget it entirely?

Sometimes questions like these consumed me with a feverish intensity; other times I didn’t care at all. Sometimes answers would come to me, as surprising as a suddenly popped balloon, with no warning whatsoever. Most of the time there were only questions.

The attendants at this place whose name I did not know were of precious little help. It was against policy, they said, to supply any answers about a resident’s past. It was very important that everything I learned be the result of spontaneous recollection; only in this way could my recovery be considered permanent and genuine.

So I had learned to mask my questions in innocuous forms, like “Who are you?” and to hoard every scrap of information that was returned to me against that time when I might have enough pieces of the puzzle to begin to put together a shape.

He said, with a firm and reassuring smile, “I am the person who is going to help you get better. You can call me Michael.”

“You’re a doctor.” A statement of the obvious. “I’m not comfortable calling you by your Christian name. It seems disrespectful.”

“It’s not, I assure you.”

We were in the garden because I longed so for the scent of clean air and the touch of the sun, for the lush ripeness of growing things and fecund earth. But the experience so far had been less than satisfactory. The colors seemed muted some- how, the greens flat and the yellows brown. The flowers had no scent. The light did not warm.

I knew there were medications that could dull the senses. But I was terrified by the thought that this muffling, foggy veil that seemed to have twined itself around my brain like spiderwebs on a dewy morning was nothing that could be induced by an injection or erased with a pill. The damage might be permanent. I might never again hear the trill of a chickadee in all its subtle nuances, or smell the perfume of spring grass, or gasp with delight over the shadow a butterfly cast on a stone path in late-summer light. The possibility filled me with such dread that I could not even ask for the truth of it.

I said, “My husband was a doctor, you know.”

“Yes, I know.”

“He was a brilliant man.”

We walked through the still and colorless garden with its soft, cool light and its pale flowers. I felt the comfort of Michael’s presence beside me, but it seemed a small thing, floating alone in a great hollow universe. I said softly, “He’s dead, isn’t he?”

“Yes.” Without hesitation, without apology. It was as though he were observing that the sky is blue, or remarking how lovely the forsythia was this year. Yes.

It was not so much sorrow that filled me, but a swelling sense of loss, a wave that crested and broke and was lost again in the sea of my despair. I wanted to weep, but could not find the tears. And I was shamed by the almost certain knowledge that, if I did cry, it would not be for the man whose face I could not remember, but for myself. He was dead. I think I had always known that.

I said, “It was the same accident that took my memory. There were no survivors.” Odd, how I simply said that, and knew it was true. Something else I must have always known.

We walked for a long time in empty silence. I said, “I’m all alone.”

“Of course you’re not. Everyone here wants to help you.”

“But they can’t, can they?” Now I turned and looked directly into the kind face of this man I did not know, but who was the only familiar thing in a world of void. “No one can help me. I think I must have read about places like these, people like me. No one ever gets better. No one ever goes home.”

“That’s not true. You’re going to get better.”

“Then help me!” I cried. “Tell me what happened to me, tell me what I’ve lost, tell me how he died! Tell me where I am and where I came from and what I have to do to get my memory back! Tell me who I am!”

Descriere

Paul and Penny Mason are spending the summer at the family lake house in a last ditch effort to save their crumbling marriage. The celebrated author of "The Alchemist" leaves the world of ancient Egypt with this chilling, modern ghost story of an unraveling family.

Notă biografică

Donna Boyd