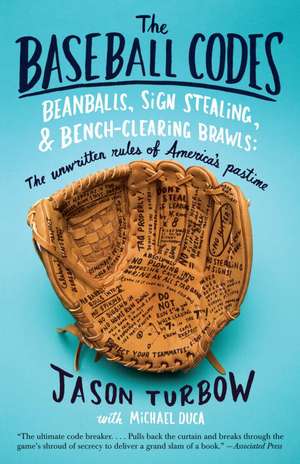

The Baseball Codes: The Unwritten Rules of America's Pastime

Autor Jason Turbow, Michael Ducaen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2011

At the heart of this book are incredible and often hilarious stories involving national heroes (like Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays) and notorious headhunters (like Bob Gibson and Don Drysdale) in a century-long series of confrontations over respect, honor, and the soul of the game. With The Baseball Codes, we see for the first time the game as it’s actually played, through the eyes of the players on the field.

With rollicking stories from the past and new perspectives on baseball’s informal rulebook, The Baseball Codes is a must for every fan.

Preț: 90.91 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 136

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.40€ • 18.89$ • 14.61£

17.40€ • 18.89$ • 14.61£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307278623

ISBN-10: 030727862X

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 133 x 202 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 030727862X

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 133 x 202 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Jason Turbow has written for The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, SportsIllustrated.com, and Slam magazine. He is a regular contributor to Giants Magazine and Athletics, and for three years served as content director for “Giants Today,” a full-page supplement in the San Francisco Chronicle that was published in conjunction with every Giants home game. He lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with his wife and two children.

Michael Duca was the first chairman of the board of Bill James’s Project Scoresheet, was a contributor to and editor of The Great American Baseball Stats Book, and has written for SportsTicker, “Giants Today” in the San Francisco Chronicle, and the Associated Press. He covers the San Jose Sharks for Examiner.com and works for the Office of the Commissioner as an official scorer and for MLB.com. He lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Michael Duca was the first chairman of the board of Bill James’s Project Scoresheet, was a contributor to and editor of The Great American Baseball Stats Book, and has written for SportsTicker, “Giants Today” in the San Francisco Chronicle, and the Associated Press. He covers the San Jose Sharks for Examiner.com and works for the Office of the Commissioner as an official scorer and for MLB.com. He lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Extras

Chapter 7

Don’t Show Players Up

It was a simple question. From the batter’s box at Candlestick Park, Willie Mays looked at Yankees pitcher Whitey Ford and, pointing toward Mickey Mantle in center field, asked, “What’s that crazy b**tard clapping about?”

What that crazy b**tard was clapping about only tangentially concerned Mays, but the Giants superstar didn’t know that at the time. It was the 1961 All-Star Game, and Ford had just struck Mays out, looking, to end the first inning. The question was posed when Ford passed by Mays as the American League defense returned to the dugout—most notably among them Mantle, hopping and applauding every step of the way, as if his team had just won the World Series. There was a good story behind it, but that didn’t much matter in the moment. Willie Mays was being shown up in front of a national baseball audience.

Under ordinary circumstances there is no acceptable reason for a player to embarrass one of his colleagues on the field. It’s the concept at the core of the unwritten rules, helping dictate when it is and isn’t appropriate to steal a base, how one should act in the batter’s box after hitting a home run, and what a player should or shouldn’t say to the media. Nobody likes to be shown up, and baseball’s Code identifies the notion in virtually all its permutations. Mantle’s display should never have happened, and Mays knew it.

Mantle had been joyous for a number of reasons. There was the strikeout itself, which was impressive because to that point Mays had hit Ford like he was playing slow-pitch softball—6-for-6 lifetime, with two homers, a triple, and an astounding 2.167 slugging percentage, all in All- Star competition. Also, Ford and Mantle had spent the previous night painting the town in San Francisco in their own inimitable way, and Ford, still feeling the effects of overindulgence, was hoping simply to survive the confrontation. Realizing that he had no idea how to approach a Mays at-bat, the left-hander opened with a curveball; Mays responded by pummeling the pitch well over four hundred feet, just foul. Ford, bleary and already half beaten, didn’t see a downside to more of the same, and went back to the curve. This time Mays hit it nearly five hundred feet, but again foul. It became clear to the pitcher that he couldn’t win this battle straight up—so he dipped into his bag of tricks.

Though Ford has admitted to doctoring baseballs in later years, at that point in his career he wasn’t well practiced in the art. Still, he was ahead in the count, it was an exhibition game, and Mays was entitled to at least one more pitch. Without much to lose, Ford spat on his throwing hand, then pretended to wipe it off on his shirt. When he released the ball, it slid rotation-free from between his fingers and sailed directly at Mays’s head, before dropping, said Ford, “from his chin to his knees” through the strike zone. Mays could do nothing but gape and wait for umpire Stan Landes to shoot up his right hand and call strike three.

To this point in the story, nobody has been shown up at all. Ford may have violated baseball’s actual rules by loading up a spitter, but cheating is fairly well tolerated within the Code. Mays’s reaction to the extreme break of the pitch may have made him look bad, but that was hardly Ford’s fault. But then came Mantle, jumping and clapping like a kid who’d just been handed tickets to the circus. It didn’t much matter that the spectacle was directed not at Mays but at Giants owner Horace Stoneham, who immediately understood the motivation behind Mantle’s antics.

Stoneham had gone out of his way to make Mantle and Ford feel at home upon their arrival in town a day earlier, using his connections at the exclusive Olympic Club to arrange a round of golf for the duo, and went so far as to enlist his son Peter as their chauffeur. Because the pair of Yankees had failed to bring golf equipment, their first stop was the pro shop, for shoes, gloves, sweaters, and rental clubs. The total came to four hundred dollars, but the club didn’t accept cash. Instead, they charged everything to Stoneham, intending to pay him back at the ballpark the following day.

That night, however, the three met at a party at the chic Mark Hopkins Hotel. Ford attempted to settle his tab on the spot, but Stoneham’s response wasn’t quite what he anticipated: The owner told him to keep his money . . . for the moment. Stoneham then proposed a wager: If Ford retired Mays the first time they faced each other the following afternoon, he owed nothing. Should the center fielder hit safely, however, Ford and Mantle would owe Stoneham eight hundred dollars, double their original debt. Ordinarily, this sort of bet would be weighted heavily in favor of the pitcher, since even the best hitters connect only three times out of ten, but Ford was aware of his track record against Mays. Nonetheless, the lefty loved a challenge even more than he loved a drink, and quickly accepted Stoneham’s terms.

Mantle, however, wasn’t so cavalier, telling Ford frankly just how bad a deal it was. “I hated to lose a sucker bet,” he said later, “and this was one of them.”

That didn’t keep Ford from sweet-talking him into accepting Stoneham’s terms. In center field the next day, Mantle found himself significantly more concerned about the potential four-hundred-dollar hole in his pocket than he was about the baseball ramifications of the Ford-Mays showdown. So, when the Giants’ star was called out on the decisive spitter, it was all Mantle could do to keep from pirouetting across the field. Said Ford, “Here it was only the end of the first inning in the All-Star Game, and he was going crazy all the way into the dugout.”

“It didn’t dawn on me right away how it must have looked to Willie and the crowd,” said Mantle. “It looked as if I was all tickled about Mays striking out because of the big rivalry [over who was the game’s pre-eminent center fielder], and in the dugout when Whitey mentioned my reaction I slapped my forehead and sputtered, ‘Aw, no . . . I didn’t . . . how could I . . . what a dumb thing.’ ”

That Mantle got away with it was largely due to the fact that Ford later explained the entire affair to Mays, much to May’s amusement. In this regard, Mantle was luckier than most players, who usually learn of their indiscretions from well-placed fastballs, not from conversation. For example, stepping out of the batter’s box once a pitcher comes set isn’t something that inspires retribution in most pitchers, but it did for Goose Gossage—in a spring-training game, no less. And Randy Johnson drilled a player in a B-squad game for swinging too hard. New York Mets closer Billy Wagner considered hitting a spring-scrimmage opponent from the University of Michigan who had the nerve to bunt on him. (“Play to win against Villanova,” the pitcher said afterward.) Nolan Ryan felt similarly when major-leaguers laid down bunts against him, and Don Drysdale and Bob Gibson were likely to knock down any opponent who dug in. All these pitchers felt justified in meting out justice for infractions that the majority of their colleagues barely noticed.

Several code violations, however, are universally abhorred. At or near the top of any pitcher’s peeves is the home-run pimp, a hitter who lingers in the batter’s box as the ball soars over the wall. The first great player to fit this bill was Minnesota’s Hall of Fame slugger Harmon Killebrew, by nature a quiet man who happened to take delight throughout the 1960s in watching his big flies leave the yard. “Killebrew was the first one I saw (do it),” said Frank Robinson. “He would stand there and watch them. But heck, he hit the ball so high, he could watch them.” Reggie Jackson, widely credited with bringing the practice to prominence in the 1970s, credits Killebrew with providing inspiration.

Jackson, of course, added panache and self-absorption to the act, combined with a thirst for attention that Killebrew never knew. During Jackson’s days with the Yankees, he went so far as to claim the final slot in batting practice because it afforded him the largest audience before which to perform. This became known as “Reggie Time,” and the slugger saw fit to bestow it upon some lucky teammate if he was unable to take that slot on a particular day.

Barry Bonds eventually became the torchbearer for home-run pimping, not only watching but twirling in the batter’s box as a matter of follow-through. David Halberstam wrote of Bonds’s mid-career antics for ESPN.com: “The pause at this moment, as we have all come to learn, is very long, plenty of time for the invisible but zen-like moment of appreciation when Barry Bonds psychically high-fives Barry Bonds and reassures him once again that there’s no one quite like him in baseball.”

Admiring one’s own longball isn’t all that sets pitchers off. When Phillies rookie Jimmy Rollins flipped his bat after hitting a home run off St. Louis reliever Steve Kline in 2001, the Cardinals pitcher went ballistic, screaming as he followed Rollins around the bases. “I called him every name in the book, tried to get him to fight,” said Kline. The pitcher stopped only upon reaching Philadelphia third baseman Scott Rolen, who was moving into the on-deck circle and alleviated the situation by assuring him that members of the Phillies would take care of it internally.

“That’s f**king Little League s**t,” said Kline after the game. “If you’re going to flip the bat, I’m going to flip your helmet next time. You’re a rookie, you respect this game for a while. . . . There’s a code. He should know better than that.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Don’t Show Players Up

It was a simple question. From the batter’s box at Candlestick Park, Willie Mays looked at Yankees pitcher Whitey Ford and, pointing toward Mickey Mantle in center field, asked, “What’s that crazy b**tard clapping about?”

What that crazy b**tard was clapping about only tangentially concerned Mays, but the Giants superstar didn’t know that at the time. It was the 1961 All-Star Game, and Ford had just struck Mays out, looking, to end the first inning. The question was posed when Ford passed by Mays as the American League defense returned to the dugout—most notably among them Mantle, hopping and applauding every step of the way, as if his team had just won the World Series. There was a good story behind it, but that didn’t much matter in the moment. Willie Mays was being shown up in front of a national baseball audience.

Under ordinary circumstances there is no acceptable reason for a player to embarrass one of his colleagues on the field. It’s the concept at the core of the unwritten rules, helping dictate when it is and isn’t appropriate to steal a base, how one should act in the batter’s box after hitting a home run, and what a player should or shouldn’t say to the media. Nobody likes to be shown up, and baseball’s Code identifies the notion in virtually all its permutations. Mantle’s display should never have happened, and Mays knew it.

Mantle had been joyous for a number of reasons. There was the strikeout itself, which was impressive because to that point Mays had hit Ford like he was playing slow-pitch softball—6-for-6 lifetime, with two homers, a triple, and an astounding 2.167 slugging percentage, all in All- Star competition. Also, Ford and Mantle had spent the previous night painting the town in San Francisco in their own inimitable way, and Ford, still feeling the effects of overindulgence, was hoping simply to survive the confrontation. Realizing that he had no idea how to approach a Mays at-bat, the left-hander opened with a curveball; Mays responded by pummeling the pitch well over four hundred feet, just foul. Ford, bleary and already half beaten, didn’t see a downside to more of the same, and went back to the curve. This time Mays hit it nearly five hundred feet, but again foul. It became clear to the pitcher that he couldn’t win this battle straight up—so he dipped into his bag of tricks.

Though Ford has admitted to doctoring baseballs in later years, at that point in his career he wasn’t well practiced in the art. Still, he was ahead in the count, it was an exhibition game, and Mays was entitled to at least one more pitch. Without much to lose, Ford spat on his throwing hand, then pretended to wipe it off on his shirt. When he released the ball, it slid rotation-free from between his fingers and sailed directly at Mays’s head, before dropping, said Ford, “from his chin to his knees” through the strike zone. Mays could do nothing but gape and wait for umpire Stan Landes to shoot up his right hand and call strike three.

To this point in the story, nobody has been shown up at all. Ford may have violated baseball’s actual rules by loading up a spitter, but cheating is fairly well tolerated within the Code. Mays’s reaction to the extreme break of the pitch may have made him look bad, but that was hardly Ford’s fault. But then came Mantle, jumping and clapping like a kid who’d just been handed tickets to the circus. It didn’t much matter that the spectacle was directed not at Mays but at Giants owner Horace Stoneham, who immediately understood the motivation behind Mantle’s antics.

Stoneham had gone out of his way to make Mantle and Ford feel at home upon their arrival in town a day earlier, using his connections at the exclusive Olympic Club to arrange a round of golf for the duo, and went so far as to enlist his son Peter as their chauffeur. Because the pair of Yankees had failed to bring golf equipment, their first stop was the pro shop, for shoes, gloves, sweaters, and rental clubs. The total came to four hundred dollars, but the club didn’t accept cash. Instead, they charged everything to Stoneham, intending to pay him back at the ballpark the following day.

That night, however, the three met at a party at the chic Mark Hopkins Hotel. Ford attempted to settle his tab on the spot, but Stoneham’s response wasn’t quite what he anticipated: The owner told him to keep his money . . . for the moment. Stoneham then proposed a wager: If Ford retired Mays the first time they faced each other the following afternoon, he owed nothing. Should the center fielder hit safely, however, Ford and Mantle would owe Stoneham eight hundred dollars, double their original debt. Ordinarily, this sort of bet would be weighted heavily in favor of the pitcher, since even the best hitters connect only three times out of ten, but Ford was aware of his track record against Mays. Nonetheless, the lefty loved a challenge even more than he loved a drink, and quickly accepted Stoneham’s terms.

Mantle, however, wasn’t so cavalier, telling Ford frankly just how bad a deal it was. “I hated to lose a sucker bet,” he said later, “and this was one of them.”

That didn’t keep Ford from sweet-talking him into accepting Stoneham’s terms. In center field the next day, Mantle found himself significantly more concerned about the potential four-hundred-dollar hole in his pocket than he was about the baseball ramifications of the Ford-Mays showdown. So, when the Giants’ star was called out on the decisive spitter, it was all Mantle could do to keep from pirouetting across the field. Said Ford, “Here it was only the end of the first inning in the All-Star Game, and he was going crazy all the way into the dugout.”

“It didn’t dawn on me right away how it must have looked to Willie and the crowd,” said Mantle. “It looked as if I was all tickled about Mays striking out because of the big rivalry [over who was the game’s pre-eminent center fielder], and in the dugout when Whitey mentioned my reaction I slapped my forehead and sputtered, ‘Aw, no . . . I didn’t . . . how could I . . . what a dumb thing.’ ”

That Mantle got away with it was largely due to the fact that Ford later explained the entire affair to Mays, much to May’s amusement. In this regard, Mantle was luckier than most players, who usually learn of their indiscretions from well-placed fastballs, not from conversation. For example, stepping out of the batter’s box once a pitcher comes set isn’t something that inspires retribution in most pitchers, but it did for Goose Gossage—in a spring-training game, no less. And Randy Johnson drilled a player in a B-squad game for swinging too hard. New York Mets closer Billy Wagner considered hitting a spring-scrimmage opponent from the University of Michigan who had the nerve to bunt on him. (“Play to win against Villanova,” the pitcher said afterward.) Nolan Ryan felt similarly when major-leaguers laid down bunts against him, and Don Drysdale and Bob Gibson were likely to knock down any opponent who dug in. All these pitchers felt justified in meting out justice for infractions that the majority of their colleagues barely noticed.

Several code violations, however, are universally abhorred. At or near the top of any pitcher’s peeves is the home-run pimp, a hitter who lingers in the batter’s box as the ball soars over the wall. The first great player to fit this bill was Minnesota’s Hall of Fame slugger Harmon Killebrew, by nature a quiet man who happened to take delight throughout the 1960s in watching his big flies leave the yard. “Killebrew was the first one I saw (do it),” said Frank Robinson. “He would stand there and watch them. But heck, he hit the ball so high, he could watch them.” Reggie Jackson, widely credited with bringing the practice to prominence in the 1970s, credits Killebrew with providing inspiration.

Jackson, of course, added panache and self-absorption to the act, combined with a thirst for attention that Killebrew never knew. During Jackson’s days with the Yankees, he went so far as to claim the final slot in batting practice because it afforded him the largest audience before which to perform. This became known as “Reggie Time,” and the slugger saw fit to bestow it upon some lucky teammate if he was unable to take that slot on a particular day.

Barry Bonds eventually became the torchbearer for home-run pimping, not only watching but twirling in the batter’s box as a matter of follow-through. David Halberstam wrote of Bonds’s mid-career antics for ESPN.com: “The pause at this moment, as we have all come to learn, is very long, plenty of time for the invisible but zen-like moment of appreciation when Barry Bonds psychically high-fives Barry Bonds and reassures him once again that there’s no one quite like him in baseball.”

Admiring one’s own longball isn’t all that sets pitchers off. When Phillies rookie Jimmy Rollins flipped his bat after hitting a home run off St. Louis reliever Steve Kline in 2001, the Cardinals pitcher went ballistic, screaming as he followed Rollins around the bases. “I called him every name in the book, tried to get him to fight,” said Kline. The pitcher stopped only upon reaching Philadelphia third baseman Scott Rolen, who was moving into the on-deck circle and alleviated the situation by assuring him that members of the Phillies would take care of it internally.

“That’s f**king Little League s**t,” said Kline after the game. “If you’re going to flip the bat, I’m going to flip your helmet next time. You’re a rookie, you respect this game for a while. . . . There’s a code. He should know better than that.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"Delicious . . . Entertaining . . . The Baseball Codes reads like a lab report by a psychologist who has been observing hostile toddlers whack one another with plastic shovels in a sandbox."

—Bruce Weber, The New York Times Book Review

“A frankly incredible book—a history and analysis of baseball’s insular culture of unwritten rules, protocols and superstitions, assembled over the course of ten years . . . I can say without hesitation that this is one of the all-time greats—a first-ballot Hall of Famer.”

—Glenn McDonald, NPR

“If baseball players adhere to a series of informal doctrines, then consider Turbow the ultimate code breaker . . . Turbow pulls back the curtain and breaks through the game’s shroud of secrecy to deliver a grand slam of a book.”

—Mike Householder, Associated Press

“A remarkably well researched book, filled with intricate details of plays from the past 100 years.”

—Larry Getlen, New York Post

“Turbow and Duca have filled a void with this entertaining, revealing survey of the varied, sometimes inscrutable unwritten rules that govern the way baseball is played by the pros.”

—Booklist

“A highly entertaining read . . . A comprehensive, sometimes hilarious guide to perhaps a misunderstood aspect of our national pastime.”

—Publishers Weekly

—Bruce Weber, The New York Times Book Review

“A frankly incredible book—a history and analysis of baseball’s insular culture of unwritten rules, protocols and superstitions, assembled over the course of ten years . . . I can say without hesitation that this is one of the all-time greats—a first-ballot Hall of Famer.”

—Glenn McDonald, NPR

“If baseball players adhere to a series of informal doctrines, then consider Turbow the ultimate code breaker . . . Turbow pulls back the curtain and breaks through the game’s shroud of secrecy to deliver a grand slam of a book.”

—Mike Householder, Associated Press

“A remarkably well researched book, filled with intricate details of plays from the past 100 years.”

—Larry Getlen, New York Post

“Turbow and Duca have filled a void with this entertaining, revealing survey of the varied, sometimes inscrutable unwritten rules that govern the way baseball is played by the pros.”

—Booklist

“A highly entertaining read . . . A comprehensive, sometimes hilarious guide to perhaps a misunderstood aspect of our national pastime.”

—Publishers Weekly

Descriere

Everyone knows baseball is a game of intricate regulations, but it is more complicated than we realize. What truly governs the game is a set of unwritten rules. In "The Baseball Codes," old-timers and all-time greats share their insights into the game's most hallowed, and least known, traditions.