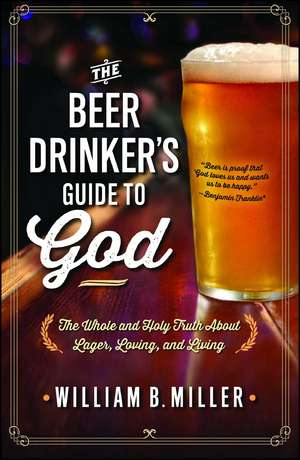

The Beer Drinker's Guide to God: The Whole and Holy Truth About Lager, Loving, and Living

Autor William B. Milleren Limba Engleză Paperback – 19 iun 2014

Father Bill believes that being upright does not mean you have to be uptight. In The Beer Drinker's Guide to God, he brews up insightful, beautifully written reflections on how alcoholic beverages can reveal the true nature of God. He weaves together stories from his life in ministry, his travels in search of the world's best Scotch, his attempts at brewing his own beer, and colorful evenings in his Texan bar. He also reflects on the lessons he's learned from roller derby, playboy bunnies, Las Vegas, and his attempts to marry Miss Universe, all while writing about generosity, sacrifice, pilgrimage, and spiritual transformation. From the deeply touching to the laugh-out-loud funny, these stories ultimately open our minds to the glory of God and our mouths to some of his more delicious creations.The Beer Drinker's Guide to God is a smart, earnest, hilarious book for those thirsty for God's truth.

Preț: 108.22 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 162

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.71€ • 21.62$ • 17.14£

20.71€ • 21.62$ • 17.14£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781476738642

ISBN-10: 1476738645

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Howard Books

Colecția Howard Books

ISBN-10: 1476738645

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Howard Books

Colecția Howard Books

Notă biografică

Father William (Bill) Miller is an Episcopal priest and the rector at St. Michael and All Angel’s Episcopal Church in Kauai, Hawaii. He is also a co-owner of Padre’s Bar, a live music venue/watering hole in Marfa, Texas. God and strong drink are two of his favorite things. Father Bill currently resides in Kauai with his dog, Nawiliwili Nelson.

Extras

The Beer Drinker’s Guide to God

The beauty of the virtue in doing penance for excess, Beautiful too that God shall save me.

The beauty of a companion who does not deny me his company,

Beautiful too the drinking horn’s society.

—“THE LOVES OF TALIESIN,” WELSH, THIRTEENTH CENTURY

Louis “Dynamite” Johnson is the best gay, black, liberal, conservative, antiwar, pro-life, eleventh-grade American history teacher I ever had. In fact, Louis Johnson is the best teacher I ever had.

I will never forget my first day in Johnson’s class. As a self-conscious adolescent introvert, I had not intended to draw attention to the debut of my “so geeky it’s hip” eyewear. My gigantic, tortoiseshell glasses made me look like a mutant horsefly wearing antique aviator goggles. It never occurred to me that I could be singled out as a living object lesson for the chapter on Charles Lindbergh and American aviation history.

I planned to blend in with my back-row desk, maintaining my eleven-year streak of nonparticipation in class discussion. However, Johnson ruined my plan by pausing in the midst of a series of inane student responses to a thought-provoking question. Apparently he assumed that, as high school juniors, we might be capable of a deep conviction, critical analysis, or original thought. What Kinky Friedman wrote about American historical figures was also applicable to our student body: “You can lead a politician to water, but you can’t make him think!”

Johnson’s pedagogical method caught us off guard. We were used to ingesting data and regurgitating it in the form of multiple-choice tests. Our former history teachers, football coaches whose biceps dwarfed their worldview, were uninterested in historical inquiry and their ethos was encapsulated in the adage “The best offense is a good defense.” As far as they were concerned, that pretty much summed up the past, present, and future of American influence in the world.

Dynamite took great delight in lobbing explosives into our heretofore unchallenged understanding of the world and America’s preeminent place therein. He encouraged us to do independent research so that when we came together in class, we could engage in informed discourse and even debate the merits of various ideas. Johnson wanted us to look at the deeper issues of causality, telling us that the removal of our red, white, and blue–tinted glasses might help us to become better patriots, and a stronger nation.

On that fateful first day of class, our American history teacher grew more exasperated with every inarticulate utterance my classmates made. Finally, Johnson looked right at me and my studious-looking spectacles. Hoping that I was seeing through the lens of illumination, he pointed at my most noticeable accessory. He shouted, as if I might be the great, wise hope, “You, the intelligent-looking young man in the back row, what do you think?”

I have no idea what came out of my mouth that day. It must have been in English, reasonably articulate, and somewhat morally sound, because I remember Mr. Johnson affirming my brilliant point by pounding his podium with the force of a Baptist preacher. To this day I could swear he gave me an “Amen.”

Talk about a setup. From that day forward, I made a concerted effort to live into Louis Johnson’s perception of me. Maybe he had seen something that really was there, or maybe he just needed glasses.

Because of his insight, I made some profound discoveries that semester. Prior to Dynamite’s influence, I had no idea that there was a large, quiet room on the premises of our school that was filled with books that could be “borrowed” by students. I always assumed that room was the assistant principal’s dungeon. Furthermore, there was a lady who lived in that room called Library Ann. She helped you find things that could make you smarter.

As an added bonus, I discovered that girls often hung out there, and they didn’t seem to mind guys with geeky glasses as long as there was a brain behind them. It was in that library, early one morning, as I was investigating LBJ’s Great Society, that the homecoming queen began to snoop around my table. After hearing a preliminary report on my findings, she proceeded to ask me out on a date. As there is only so much one can learn from books, I was too stupid to say “Yes!”

But something happened to me in Louis Johnson’s American history class. I got smart.

I had failed a geometry class the year before. An F brings a GPA to a point of almost no return, but I made so many A’s after the “Johnson Mandate” that I was inducted into the National Honor Society just before graduation. What’s more, Johnson challenged me to integrate my philosophical and theological convictions into my political and historical world-view. He was the teacher who convinced me that George Bernard Shaw was right: those who cannot change their minds, cannot change anything. I would never look at anything un-critically again, and I would never see the world in the same way.

Just as events in American history were not always black-and-white, issues in Johnson’s class were not always clear-cut. During one discussion, no one could provide a reason why we should care about what happened to non-Americans. Johnson turned to me, pointed, and boomed, “Bill!” I boomed right back, “Because they are human beings!” “Because they are human beings” became the class mantra for the rest of the semester. During another discussion, he attempted to help us understand that other cultures, even those we have sometimes labeled “primitive,” were also innovative and intelligent. American know-how was not the only knowledge out there. While Johnson was unsuccessfully trying to coax “crossbow” out of us as the invention of Native Americans, I had a momentary relapse and got in touch with my inner idiot. “Flaming arrows,” I offered. I must not have been wearing my glasses that day. Johnson seemed to relish pointing out to me that fire had been invented several years prior. I’m sure even Einstein had an off day.

Sometimes the work of challenging accepted attitudes and ideals made us downright uncomfortable. Once, defending the Palestinian cause and criticizing America’s unwavering support for Israel, Johnson got a classmate so worked up he stormed out of class, accusing Johnson of being “anti-Semitic.” Another time, a majority of students and faculty were outraged when Johnson openly challenged a Vietnam War hero over his interpretation of the rationale and success of the war. “That’s just disrespectful,” my fellow classmate intoned. Later he would marry an army recruiter. Later still, they both became Lutheran pastors and liberal Democrats. Hey, if you can’t change your mind.

I still change my mind, and I still recall that initial explosive force that started to knock the scales from my eyes and open me up to alternative realities. Years later, I still attempt to see myself as “that intelligent-looking young man,” although these days I am forced to admit that one out of three ain’t bad.

![]()

There is an optical phenomenon, mostly among males who imbibe, that we have come to call “beer goggles.” After the consumption of an indeterminate number of beers, the brew begins to travel directly from the stomach to the brain, then through the optic nerve, filling the vitreous and aqueous humors with material that is funny only to oneself, and perhaps to the eventual focus of the goggles.

As this eye-opening phenomenon develops, the visual axis is completely inverted. The retinal blood vessels become amber-colored and a white foam begins to coat the entire cornea, distorting one’s vision, but in a most positive way. The lens of the eye begins to focus intently on a previously undesirable object of affection. Right before one’s beer-goggle-covered eyes, this person grows in wisdom, stature, and beauty. Though a temporary condition, the beer goggles may be removed only by a good friend in possession of your car keys. Such lenses also tend to dissipate in the morning light.

As far as I am aware, I have suffered only one serious case of this visual disorder. I was on Sixth Street in Austin, in a very crowded club, when I became incredibly attracted to a striking young woman who was there with her sister. She was obviously seeing her own date through beer goggles, a loser (that is, “not me”) upon whom she was far too fixated. Initially unimpressed with her sibling, I downed an entire case of Mexican beer and began to view the sister with a south-of-the-border version of beer goggles called “Cervezavision.” Through Cervezavision, I began to see the sister as a virtual twin to the true object of my desire. The sister was not a twin. In fact, not nearly a twin. In fact, according to my wingman for the evening, it is conceivable that she was actually her brother. Still, since my brain was filled with an oxygen-depleting liquid, my “better judgment” decided it was time for a siesta and I made a bold move.

Although I have a friend whose nightlife philosophy can be summarized as “Go ugly early,” I have never subscribed to this theory. Fortunately, my good friend and wingman assumed the role of another helpful winged creature, pulled me away from locking lips with the non-twin, and gave me a lecture on optical illusions. Thank God I was not drinking alone.

Once, a normally insightful friend of mine came down with an acute case of this condition. He and I were hanging out at a funky little pub in Hong Kong where I was completely smitten with my exotically beautiful Nepalese server. I was off in my own private Kathmandu when I finally returned to the table and found my friend had somehow made space for two Norwegian women. In fact, he made a lot of space. I have traveled to Norway, and I can attest to the incredibly attractive people in this Nordic wonderland. These specimens, however, were not.

As I gazed upon the Norwegians, the defensive line of the 1986 Super Bowl Champion Chicago Bears came to mind. These ladies made William “Refrigerator” Perry look not only small, but also highly desirable. My friend leaned in to me and said, “Dude, these chicks are hot.” I leaned back to him and said, “Dude, these chicks are not. You are now going to get up from this table and follow me back to the hotel. No, you may not have another beer. Trust me on this one. Tomorrow morning you will thank me for this.”

And he did.

Another friend with what one might also call “Alternavision” is the Reverend James Douglas Hunter. Jimmy Hunter is an African-American Missionary Baptist pastor in Texas. He is my most stylish friend. His shoes have Italian names and are crafted from the hides of the world’s most exotic animals. When he wears his full-length black leather coat, he comes across as smooth as the silk shirt underneath. When we are out on the town together, people often stop and stare at us as if we are famous. Let me rephrase that. When we are out on the town together, people often stop and stare at him as if he is famous.

What’s really fun about the Reverend Hunter is that if he suspects there might be a Baptist lurking nearby, he will order his margaritas in a coffee cup. Adjacent tables are always astounded that so much caffeine can put a man to sleep.

I met Jimmy Hunter at a funeral in East Austin. I had accepted a call to a predominantly African-American parish where the local custom was for all ministers who had any relation to any relation of the deceased to participate. This was not only my first funeral, it was my first public appearance in the neighborhood. With some trepidation, I walked into the David Chapel Missionary Baptist Church to participate in the funeral for someone I did not know, among ministers I did not know, according to a religious tradition with which I was completely unfamiliar. They were all wearing ties. I was wearing a clerical collar. They were all carrying Bibles. I was carrying my Episcopal Book of Common Prayer. They were all men of color. I am more pale than ale. They were all professionals when it comes to extemporaneous speaking. I am an Episcopalian, so I read my prayers verbatim. They’ve memorized half the Bible. I’ve read some of it. Their services go on for days. My services are done in one hour. They mostly don’t drink. I needed a beer.

As soon as I walked in the door, I spotted the reverend. He was smiling and nodding at me as if he had spotted a long-lost friend. He walked over and greeted me: “Welcome. We’re so glad you’re here.” He told me to follow him and do what he did. I almost sat in his lap, I was so comforted by his presence. I managed to look pious for two and a half hours, and, as we began to process out, the senior pastor nudged me and said, “Pastor, won’t you share some scripture?” The prayer book comes in handy from time to time. After the service, the Reverend Hunter told me that if he hadn’t known otherwise, he’d have sworn I was a Missionary Baptist. He was lying, but in a nice way. We’ve been friends ever since.

We’ve come a long way since that initial nerve-racking encounter. Our time together is now much livelier. We’ve had a good-natured, tongue-in-cheek contest going on for many years as to which one of us is “the Greatest in the Kingdom of God.” Our opinions differ on that. We’ve debated facetiously over the years regarding the superiority of our respective preaching styles, intellectual prowess, spiritual depth, biblical knowledge, congregational growth, teaching ability, motivating force, musical preferences, and impact on the world at large. Each of us is always pointing out how God has most recently revealed his overwhelming preference for one at the expense of the other. I was ahead in the count and just couldn’t leave well enough alone.

One evening I was feeling filled with the Holy Spirit as our conversation turned toward a hero to both of us: the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. We admired King’s ability to integrate theological understanding with decisive and life-changing action. Some people talk the talk. Some people walk the walk. King did both. Despite Dr. King’s preoccupation with selfless service as the core of Christian faith, I decided to use him as another stepping-stone on the way to my rightful place at the right hand of God.

“You know, Jimmy,” I reasoned, “it is obvious to me that, just as God chose Dr. King to be a great prophet in his time, so God has chosen me as the greatest prophet of our generation, far greater than you anyway. I make this observation because King’s birthday, as you know, is January fifteenth. But what you don’t know, my dear Reverend Hunter, is that January sixteenth, the very next day, is my birthday. It is readily apparent that this is the sign we have been seeking to determine, once and for all, who is greatest among us. When it comes to you and me, my lesser brother, you are Howard Cosell to my Muhammad Ali. I am the greatest in God’s kingdom!”

The Reverend Hunter looked at me as though shocked and deeply disturbed, as if he had just lost a great and final battle. Then the twinkle in his eye became a knowing if not superior smile.

“Just so I am clear,” he began. “You assume that you are the greatest in God’s kingdom because the great prophet, Martin Luther King, was born on January fifteenth and you were born on January sixteenth?”

“That is correct, ‘O Ye of Smaller Stature,’ ” I replied.

Nodding his head as if to affirm my logic, he stood up and towered over me, bellowing the prophetic question, “And do you know when my birthday is?” I was about to offer the day after Groundhog Day as a possibility when he thundered forth, as only a surefire Baptist preacher can do, “December twenty-sixth!”

Okay, so I am the second greatest in God’s kingdom.

As enlightening as that revelatory moment was, the Prophet James was not finished opening my eyes to greater realities. I fondly remember visiting him just after he had accepted a call to a Missionary Baptist Church in Port Arthur, Texas. “It’s the silk-stocking congregation,” he told me, still in competitive mode even after he had handily won the birthday contest.

Port Arthur is part of the so-called Golden Triangle of Southeast Texas, with the cities of Beaumont and Orange completing the polygon. Neither obtuse nor acute, this triangle is more of the oblique variety. That is, you have to tilt your head a bit to find the proper viewing angle and look a little harder to find the gleam. Over the years, the gold has lost some of its luster. Port Arthur is a town that has endured white flight, polluting petrochemical plants, territorial tension after an influx of Vietnamese shrimp boats, a vacated downtown, corrupt politicians, and economic downturn. But it’s still a pretty interesting place. It is no longer the confining and conforming place it was fifty years ago. These days you can take one part Cajun-spiced alligator, mix in some swampy blues and urban hip-hop, throw in a pinch of cowpoke and Texas football, and you get Port Arthur. It is a town that has given the world the painter Robert Rauschenberg, football coach Jimmy Johnson, and the legendary singer Janis Joplin. Driving around the ramshackle streets of Port Arthur, you begin to understand how a little white girl could wail the blues with conviction and how Rauschenberg’s Combines of trash and found objects made artistic sense, and also why Jimmy Johnson now lives in Miami.

The Reverend Hunter drove me over Rainbow Bridge and eventually to what’s left of Pleasure Island. Years ago it resembled Coney Island with a big amusement park and an Olympic-sized swimming pool. Now there are a few lonely sailboats, some scraggly fields, and a crumbling parking lot.

We drove to the top of the bridge to get a view of the city below upon our return. There was a barge or two in the distance, a meandering, all-but-forgotten waterway, and a neighborhood of coastal houses that seemed to be standing on stilts just to be noticed. I was about to say something stupid regarding the depressing ugliness of the landscape when the Reverend Hunter took his hand off the steering wheel and waved it over the scene ahead and below.

“Isn’t it beautiful?” he asked. “From up here, it looks just like a postcard.”

I looked again. Blinked my eyes. Tilted my head. Refocused my gaze. The water was glistening with the first hint of a setting sun. The houses below were painted the most vibrant colors. The swampland appeared as a patchwork quilt of alligator green and golden brown. And the Reverend Hunter was looking as stylish as ever.

Perhaps that is why they call the prophets seers. They see things most of us miss. They view that which is in front of them through a lens that transforms reality right before their eyes into images of radiance. Mere eyesight becomes rare insight.

I wonder what the world would look like if it didn’t require beer goggles to behold such sights, if we no longer saw dimly a distorted reality, but clearly focused on God’s great vision for all creation. I wonder what perspective might appear if each day I removed the scales of skepticism from my eyes and looked through the lens of a more loving and appreciative Alternavision.

Dynamite, I’ll bet. And beautiful, too.

Too beautiful.

1

BEER GOGGLES

The beauty of the virtue in doing penance for excess, Beautiful too that God shall save me.

The beauty of a companion who does not deny me his company,

Beautiful too the drinking horn’s society.

—“THE LOVES OF TALIESIN,” WELSH, THIRTEENTH CENTURY

Louis “Dynamite” Johnson is the best gay, black, liberal, conservative, antiwar, pro-life, eleventh-grade American history teacher I ever had. In fact, Louis Johnson is the best teacher I ever had.

I will never forget my first day in Johnson’s class. As a self-conscious adolescent introvert, I had not intended to draw attention to the debut of my “so geeky it’s hip” eyewear. My gigantic, tortoiseshell glasses made me look like a mutant horsefly wearing antique aviator goggles. It never occurred to me that I could be singled out as a living object lesson for the chapter on Charles Lindbergh and American aviation history.

I planned to blend in with my back-row desk, maintaining my eleven-year streak of nonparticipation in class discussion. However, Johnson ruined my plan by pausing in the midst of a series of inane student responses to a thought-provoking question. Apparently he assumed that, as high school juniors, we might be capable of a deep conviction, critical analysis, or original thought. What Kinky Friedman wrote about American historical figures was also applicable to our student body: “You can lead a politician to water, but you can’t make him think!”

Johnson’s pedagogical method caught us off guard. We were used to ingesting data and regurgitating it in the form of multiple-choice tests. Our former history teachers, football coaches whose biceps dwarfed their worldview, were uninterested in historical inquiry and their ethos was encapsulated in the adage “The best offense is a good defense.” As far as they were concerned, that pretty much summed up the past, present, and future of American influence in the world.

Dynamite took great delight in lobbing explosives into our heretofore unchallenged understanding of the world and America’s preeminent place therein. He encouraged us to do independent research so that when we came together in class, we could engage in informed discourse and even debate the merits of various ideas. Johnson wanted us to look at the deeper issues of causality, telling us that the removal of our red, white, and blue–tinted glasses might help us to become better patriots, and a stronger nation.

On that fateful first day of class, our American history teacher grew more exasperated with every inarticulate utterance my classmates made. Finally, Johnson looked right at me and my studious-looking spectacles. Hoping that I was seeing through the lens of illumination, he pointed at my most noticeable accessory. He shouted, as if I might be the great, wise hope, “You, the intelligent-looking young man in the back row, what do you think?”

I have no idea what came out of my mouth that day. It must have been in English, reasonably articulate, and somewhat morally sound, because I remember Mr. Johnson affirming my brilliant point by pounding his podium with the force of a Baptist preacher. To this day I could swear he gave me an “Amen.”

Talk about a setup. From that day forward, I made a concerted effort to live into Louis Johnson’s perception of me. Maybe he had seen something that really was there, or maybe he just needed glasses.

Because of his insight, I made some profound discoveries that semester. Prior to Dynamite’s influence, I had no idea that there was a large, quiet room on the premises of our school that was filled with books that could be “borrowed” by students. I always assumed that room was the assistant principal’s dungeon. Furthermore, there was a lady who lived in that room called Library Ann. She helped you find things that could make you smarter.

As an added bonus, I discovered that girls often hung out there, and they didn’t seem to mind guys with geeky glasses as long as there was a brain behind them. It was in that library, early one morning, as I was investigating LBJ’s Great Society, that the homecoming queen began to snoop around my table. After hearing a preliminary report on my findings, she proceeded to ask me out on a date. As there is only so much one can learn from books, I was too stupid to say “Yes!”

But something happened to me in Louis Johnson’s American history class. I got smart.

I had failed a geometry class the year before. An F brings a GPA to a point of almost no return, but I made so many A’s after the “Johnson Mandate” that I was inducted into the National Honor Society just before graduation. What’s more, Johnson challenged me to integrate my philosophical and theological convictions into my political and historical world-view. He was the teacher who convinced me that George Bernard Shaw was right: those who cannot change their minds, cannot change anything. I would never look at anything un-critically again, and I would never see the world in the same way.

Just as events in American history were not always black-and-white, issues in Johnson’s class were not always clear-cut. During one discussion, no one could provide a reason why we should care about what happened to non-Americans. Johnson turned to me, pointed, and boomed, “Bill!” I boomed right back, “Because they are human beings!” “Because they are human beings” became the class mantra for the rest of the semester. During another discussion, he attempted to help us understand that other cultures, even those we have sometimes labeled “primitive,” were also innovative and intelligent. American know-how was not the only knowledge out there. While Johnson was unsuccessfully trying to coax “crossbow” out of us as the invention of Native Americans, I had a momentary relapse and got in touch with my inner idiot. “Flaming arrows,” I offered. I must not have been wearing my glasses that day. Johnson seemed to relish pointing out to me that fire had been invented several years prior. I’m sure even Einstein had an off day.

Sometimes the work of challenging accepted attitudes and ideals made us downright uncomfortable. Once, defending the Palestinian cause and criticizing America’s unwavering support for Israel, Johnson got a classmate so worked up he stormed out of class, accusing Johnson of being “anti-Semitic.” Another time, a majority of students and faculty were outraged when Johnson openly challenged a Vietnam War hero over his interpretation of the rationale and success of the war. “That’s just disrespectful,” my fellow classmate intoned. Later he would marry an army recruiter. Later still, they both became Lutheran pastors and liberal Democrats. Hey, if you can’t change your mind.

I still change my mind, and I still recall that initial explosive force that started to knock the scales from my eyes and open me up to alternative realities. Years later, I still attempt to see myself as “that intelligent-looking young man,” although these days I am forced to admit that one out of three ain’t bad.

There is an optical phenomenon, mostly among males who imbibe, that we have come to call “beer goggles.” After the consumption of an indeterminate number of beers, the brew begins to travel directly from the stomach to the brain, then through the optic nerve, filling the vitreous and aqueous humors with material that is funny only to oneself, and perhaps to the eventual focus of the goggles.

As this eye-opening phenomenon develops, the visual axis is completely inverted. The retinal blood vessels become amber-colored and a white foam begins to coat the entire cornea, distorting one’s vision, but in a most positive way. The lens of the eye begins to focus intently on a previously undesirable object of affection. Right before one’s beer-goggle-covered eyes, this person grows in wisdom, stature, and beauty. Though a temporary condition, the beer goggles may be removed only by a good friend in possession of your car keys. Such lenses also tend to dissipate in the morning light.

As far as I am aware, I have suffered only one serious case of this visual disorder. I was on Sixth Street in Austin, in a very crowded club, when I became incredibly attracted to a striking young woman who was there with her sister. She was obviously seeing her own date through beer goggles, a loser (that is, “not me”) upon whom she was far too fixated. Initially unimpressed with her sibling, I downed an entire case of Mexican beer and began to view the sister with a south-of-the-border version of beer goggles called “Cervezavision.” Through Cervezavision, I began to see the sister as a virtual twin to the true object of my desire. The sister was not a twin. In fact, not nearly a twin. In fact, according to my wingman for the evening, it is conceivable that she was actually her brother. Still, since my brain was filled with an oxygen-depleting liquid, my “better judgment” decided it was time for a siesta and I made a bold move.

Although I have a friend whose nightlife philosophy can be summarized as “Go ugly early,” I have never subscribed to this theory. Fortunately, my good friend and wingman assumed the role of another helpful winged creature, pulled me away from locking lips with the non-twin, and gave me a lecture on optical illusions. Thank God I was not drinking alone.

Once, a normally insightful friend of mine came down with an acute case of this condition. He and I were hanging out at a funky little pub in Hong Kong where I was completely smitten with my exotically beautiful Nepalese server. I was off in my own private Kathmandu when I finally returned to the table and found my friend had somehow made space for two Norwegian women. In fact, he made a lot of space. I have traveled to Norway, and I can attest to the incredibly attractive people in this Nordic wonderland. These specimens, however, were not.

As I gazed upon the Norwegians, the defensive line of the 1986 Super Bowl Champion Chicago Bears came to mind. These ladies made William “Refrigerator” Perry look not only small, but also highly desirable. My friend leaned in to me and said, “Dude, these chicks are hot.” I leaned back to him and said, “Dude, these chicks are not. You are now going to get up from this table and follow me back to the hotel. No, you may not have another beer. Trust me on this one. Tomorrow morning you will thank me for this.”

And he did.

Another friend with what one might also call “Alternavision” is the Reverend James Douglas Hunter. Jimmy Hunter is an African-American Missionary Baptist pastor in Texas. He is my most stylish friend. His shoes have Italian names and are crafted from the hides of the world’s most exotic animals. When he wears his full-length black leather coat, he comes across as smooth as the silk shirt underneath. When we are out on the town together, people often stop and stare at us as if we are famous. Let me rephrase that. When we are out on the town together, people often stop and stare at him as if he is famous.

What’s really fun about the Reverend Hunter is that if he suspects there might be a Baptist lurking nearby, he will order his margaritas in a coffee cup. Adjacent tables are always astounded that so much caffeine can put a man to sleep.

I met Jimmy Hunter at a funeral in East Austin. I had accepted a call to a predominantly African-American parish where the local custom was for all ministers who had any relation to any relation of the deceased to participate. This was not only my first funeral, it was my first public appearance in the neighborhood. With some trepidation, I walked into the David Chapel Missionary Baptist Church to participate in the funeral for someone I did not know, among ministers I did not know, according to a religious tradition with which I was completely unfamiliar. They were all wearing ties. I was wearing a clerical collar. They were all carrying Bibles. I was carrying my Episcopal Book of Common Prayer. They were all men of color. I am more pale than ale. They were all professionals when it comes to extemporaneous speaking. I am an Episcopalian, so I read my prayers verbatim. They’ve memorized half the Bible. I’ve read some of it. Their services go on for days. My services are done in one hour. They mostly don’t drink. I needed a beer.

As soon as I walked in the door, I spotted the reverend. He was smiling and nodding at me as if he had spotted a long-lost friend. He walked over and greeted me: “Welcome. We’re so glad you’re here.” He told me to follow him and do what he did. I almost sat in his lap, I was so comforted by his presence. I managed to look pious for two and a half hours, and, as we began to process out, the senior pastor nudged me and said, “Pastor, won’t you share some scripture?” The prayer book comes in handy from time to time. After the service, the Reverend Hunter told me that if he hadn’t known otherwise, he’d have sworn I was a Missionary Baptist. He was lying, but in a nice way. We’ve been friends ever since.

We’ve come a long way since that initial nerve-racking encounter. Our time together is now much livelier. We’ve had a good-natured, tongue-in-cheek contest going on for many years as to which one of us is “the Greatest in the Kingdom of God.” Our opinions differ on that. We’ve debated facetiously over the years regarding the superiority of our respective preaching styles, intellectual prowess, spiritual depth, biblical knowledge, congregational growth, teaching ability, motivating force, musical preferences, and impact on the world at large. Each of us is always pointing out how God has most recently revealed his overwhelming preference for one at the expense of the other. I was ahead in the count and just couldn’t leave well enough alone.

One evening I was feeling filled with the Holy Spirit as our conversation turned toward a hero to both of us: the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. We admired King’s ability to integrate theological understanding with decisive and life-changing action. Some people talk the talk. Some people walk the walk. King did both. Despite Dr. King’s preoccupation with selfless service as the core of Christian faith, I decided to use him as another stepping-stone on the way to my rightful place at the right hand of God.

“You know, Jimmy,” I reasoned, “it is obvious to me that, just as God chose Dr. King to be a great prophet in his time, so God has chosen me as the greatest prophet of our generation, far greater than you anyway. I make this observation because King’s birthday, as you know, is January fifteenth. But what you don’t know, my dear Reverend Hunter, is that January sixteenth, the very next day, is my birthday. It is readily apparent that this is the sign we have been seeking to determine, once and for all, who is greatest among us. When it comes to you and me, my lesser brother, you are Howard Cosell to my Muhammad Ali. I am the greatest in God’s kingdom!”

The Reverend Hunter looked at me as though shocked and deeply disturbed, as if he had just lost a great and final battle. Then the twinkle in his eye became a knowing if not superior smile.

“Just so I am clear,” he began. “You assume that you are the greatest in God’s kingdom because the great prophet, Martin Luther King, was born on January fifteenth and you were born on January sixteenth?”

“That is correct, ‘O Ye of Smaller Stature,’ ” I replied.

Nodding his head as if to affirm my logic, he stood up and towered over me, bellowing the prophetic question, “And do you know when my birthday is?” I was about to offer the day after Groundhog Day as a possibility when he thundered forth, as only a surefire Baptist preacher can do, “December twenty-sixth!”

Okay, so I am the second greatest in God’s kingdom.

As enlightening as that revelatory moment was, the Prophet James was not finished opening my eyes to greater realities. I fondly remember visiting him just after he had accepted a call to a Missionary Baptist Church in Port Arthur, Texas. “It’s the silk-stocking congregation,” he told me, still in competitive mode even after he had handily won the birthday contest.

Port Arthur is part of the so-called Golden Triangle of Southeast Texas, with the cities of Beaumont and Orange completing the polygon. Neither obtuse nor acute, this triangle is more of the oblique variety. That is, you have to tilt your head a bit to find the proper viewing angle and look a little harder to find the gleam. Over the years, the gold has lost some of its luster. Port Arthur is a town that has endured white flight, polluting petrochemical plants, territorial tension after an influx of Vietnamese shrimp boats, a vacated downtown, corrupt politicians, and economic downturn. But it’s still a pretty interesting place. It is no longer the confining and conforming place it was fifty years ago. These days you can take one part Cajun-spiced alligator, mix in some swampy blues and urban hip-hop, throw in a pinch of cowpoke and Texas football, and you get Port Arthur. It is a town that has given the world the painter Robert Rauschenberg, football coach Jimmy Johnson, and the legendary singer Janis Joplin. Driving around the ramshackle streets of Port Arthur, you begin to understand how a little white girl could wail the blues with conviction and how Rauschenberg’s Combines of trash and found objects made artistic sense, and also why Jimmy Johnson now lives in Miami.

The Reverend Hunter drove me over Rainbow Bridge and eventually to what’s left of Pleasure Island. Years ago it resembled Coney Island with a big amusement park and an Olympic-sized swimming pool. Now there are a few lonely sailboats, some scraggly fields, and a crumbling parking lot.

We drove to the top of the bridge to get a view of the city below upon our return. There was a barge or two in the distance, a meandering, all-but-forgotten waterway, and a neighborhood of coastal houses that seemed to be standing on stilts just to be noticed. I was about to say something stupid regarding the depressing ugliness of the landscape when the Reverend Hunter took his hand off the steering wheel and waved it over the scene ahead and below.

“Isn’t it beautiful?” he asked. “From up here, it looks just like a postcard.”

I looked again. Blinked my eyes. Tilted my head. Refocused my gaze. The water was glistening with the first hint of a setting sun. The houses below were painted the most vibrant colors. The swampland appeared as a patchwork quilt of alligator green and golden brown. And the Reverend Hunter was looking as stylish as ever.

Perhaps that is why they call the prophets seers. They see things most of us miss. They view that which is in front of them through a lens that transforms reality right before their eyes into images of radiance. Mere eyesight becomes rare insight.

I wonder what the world would look like if it didn’t require beer goggles to behold such sights, if we no longer saw dimly a distorted reality, but clearly focused on God’s great vision for all creation. I wonder what perspective might appear if each day I removed the scales of skepticism from my eyes and looked through the lens of a more loving and appreciative Alternavision.

Dynamite, I’ll bet. And beautiful, too.

Too beautiful.

Recenzii

"Bill Miller gives religion a good name. His book had me laughing out loud in parts and highlighting other sections for later reference. Buy this book, read it, then toast to spiritual transformation."

"The well-schooled theologian or the purveyor of spirits will both savor The Beer Drinker’s Guide to God ."

“In The Beer Drinker’s Guide to God, Father Bill Miller writes with eloquence and great humor—two qualities missing in much of Christian writing today—to remind us that Christianity is a religion of joy, celebration, and love. Father Miller’s sermons are crafted like parables, and so is this wonderful, joyous, profound, inspiring, wise, and deeply funny book, which strikes the perfect note and doesn’t miss a beat.”

"The well-schooled theologian or the purveyor of spirits will both savor The Beer Drinker’s Guide to God ."

“In The Beer Drinker’s Guide to God, Father Bill Miller writes with eloquence and great humor—two qualities missing in much of Christian writing today—to remind us that Christianity is a religion of joy, celebration, and love. Father Miller’s sermons are crafted like parables, and so is this wonderful, joyous, profound, inspiring, wise, and deeply funny book, which strikes the perfect note and doesn’t miss a beat.”

Descriere

Written by an Episcopalian priest-slash-bar owner, this thoughtful, well-written book of spiritual essays distills lessons about the character of God