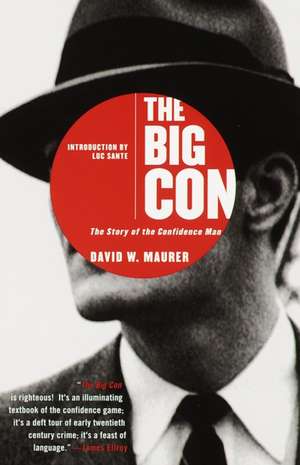

The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man

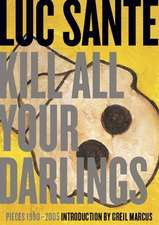

Autor David W. Maurer Luc Santeen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 1999

The Big Con is a treasure trove of American lingo (the write, the rag, the payoff, ropers, shills, the cold poke, the convincer, to put on the send) and indelible characters (Yellow Kid Weil, Barney the Patch, the Seldom Seen Kid, Limehouse Chappie, Larry the Lug). It served as a source for the Oscar-winning film The Sting and will delight fans of such writers as David Mamet, Jim Thompson, Elmore Leonard, and William Burroughs for its droll, utterly authoritative look at the timeless pursuit of relieving one's fellow man of his surplus cash.

Preț: 100.47 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 151

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.23€ • 19.96$ • 16.03£

19.23€ • 19.96$ • 16.03£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 03-17 martie

Livrare express 15-21 februarie pentru 20.24 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385495387

ISBN-10: 0385495382

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Ediția:Anchor Books.

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0385495382

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Ediția:Anchor Books.

Editura: Anchor Books

Extras

A Word About Confidence Men

The grift has a gentle touch. It takes its toll from the verdant sucker by means of the skilled hand or the sharp wit. In this, it differs from all other forms of crime, and especially from the heavy-rackets. It never employs violence to separate the mark from his money. Of all the grifters, the confidence man is the aristocrat.

Although the confidence man is sometimes classed with professional thieves, pickpockets, and gamblers, he is really not a thief at all because he does no actual stealing. The trusting victim literally thrusts a fat bank roll into his hands. It is a point of pride with him that he does not have to steal.

Confidence men are not "crooks" in the ordinary sense of the word. They are suave, slick, and capable. Their depredations are very much on the genteel side. Because of their high intelligence, their solid organization, the widespread connivance of the law, and the fact that the victim must virtually admit criminal intentions himself if he wishes to prosecute, society has been neither willing nor able to avenge itself effectively. Relatively few good con men are ever brought to trial; of those who are tried, few are convicted; of those who are convicted, even fewer ever serve out their full sentences. Many successful operators have never a day in prison to pay for their merry and lucrative lives spent in fleecing willing marks on the big-con games.

A confidence man prospers only because of the fundamental dishonesty of his victim. First, he inspires a firm belief in his own integrity. Second, he brings into play powerful and well-nigh irresistible forces to excite the cupidity of the mark. Then he allows the victim to make large sums of money by means of dealings which are explained to him as being dishonest--and hence a "sure thing." As the lust for large and easy profits is fanned into a hot flame, the mark puts all his scruples behind him. He closes out his bank account, liquidates his property, borrows from his friends, embezzles from his employer or his clients. In the mad frenzy of cheating someone else, he is unaware of the fact that he is the real victim, carefully selected and fatted for the kill. Thus arises the trite but none the less sage maxim: "You can't cheat an honest man."

This fine old principle rules all confidence games, big and little, from a simple three-card monte or shell game in a shady corner of a country fair grounds to the intricate pay-off or rag, played against a big store replete with expensive props and manned by suave experts. The three-card-monte grifter takes a few dollars from a willing farmer here and there; the big-con men take thousands or hundreds of thousands from those who have it. But the principle is always the same.

This accounts for the fact that it has been found very difficult to prosecute confidence men successfully. At the same time it explains why so little of the true nature of confidence games is known to the public, for once a victim is fleeced he often proves to be a most reluctant and untruthful witness against the men who have taken his money. By the same token, confidence men are hardly criminals in the usual sense of the word, for they prosper through a superb knowledge of human nature; they are set apart from those who employ the machine-gun, the blackjack, or the acetylene torch. Their methods differ more in degree than in kind from those employed by more legitimate forms of business.

Modern con men use at present only three big-con games, and only two of these are now used extensively. In addition, there are scores of short-con games which seem to enjoy periodic bursts of activity, followed by alternate periods of obsolescence. Some of these short-con games, when played by big-time professionals who apply the principles of the big con to them, attain very respectable status as devices to separate the mark from his money.

The three big-con games, the wire, the rag, and the pay-off, have in some forty years of their existence taken a staggering toll from a gullible public. No one knows just how much the total is because many touches, especially large ones, never come to light; both con men and police officials agree that roughly ninety per cent of the victims never complain to the police. Some professionals estimate that these three games alone have produced more illicit profit for the operators and for the law than all other forms of professional crime (excepting violations of the prohibition law) over the same period of time. However that may be, it is very certain that they have been immensely profitable.

All confidence games, big and little, have certain similar underlying principles; all of them progress through certain fundamental stages to an inevitable conclusion; while these stages or steps may vary widely in detail from type to type of game, the principles upon which they are based remain the same and are immediately recognizable. In the big-con games the steps are these:

1. Locating and investigating a well-to-do victim. (Putting the mark up.)

2. Gaining the victim's confidence. (Playing the con for him.)

3. Steering him to meet the insideman. (Roping the mark.)

4. Permitting the insideman to show him how he can make a large amount of money dishonestly. (Telling him the tale.)

5. Allowing the victim to make a substantial profit. (Giving him the convincer.)

6. Determining exactly how much he will invest. (Giving him the breakdown.)

7. Sending him home for this amount of money. (Putting him on the send.)

8. Playing him against a big store and fleecing him. (Taking off the touch.)

9. Getting him out of the way as quietly as possible. (Blowing him off.)

10. Forestalling action by the law. (Putting in the fix.)

The big-con games did not spring full-fledged into existence. The principles on which they operate are as old as civilization. But their immediate evolution is closely knit with the invention and development of the big store, a fake gambling club or broker's office, in which the victim is swindled. And within the twentieth century they have, from the criminal's point of view, reached a very high state of perfection.

The grift has a gentle touch. It takes its toll from the verdant sucker by means of the skilled hand or the sharp wit. In this, it differs from all other forms of crime, and especially from the heavy-rackets. It never employs violence to separate the mark from his money. Of all the grifters, the confidence man is the aristocrat.

Although the confidence man is sometimes classed with professional thieves, pickpockets, and gamblers, he is really not a thief at all because he does no actual stealing. The trusting victim literally thrusts a fat bank roll into his hands. It is a point of pride with him that he does not have to steal.

Confidence men are not "crooks" in the ordinary sense of the word. They are suave, slick, and capable. Their depredations are very much on the genteel side. Because of their high intelligence, their solid organization, the widespread connivance of the law, and the fact that the victim must virtually admit criminal intentions himself if he wishes to prosecute, society has been neither willing nor able to avenge itself effectively. Relatively few good con men are ever brought to trial; of those who are tried, few are convicted; of those who are convicted, even fewer ever serve out their full sentences. Many successful operators have never a day in prison to pay for their merry and lucrative lives spent in fleecing willing marks on the big-con games.

A confidence man prospers only because of the fundamental dishonesty of his victim. First, he inspires a firm belief in his own integrity. Second, he brings into play powerful and well-nigh irresistible forces to excite the cupidity of the mark. Then he allows the victim to make large sums of money by means of dealings which are explained to him as being dishonest--and hence a "sure thing." As the lust for large and easy profits is fanned into a hot flame, the mark puts all his scruples behind him. He closes out his bank account, liquidates his property, borrows from his friends, embezzles from his employer or his clients. In the mad frenzy of cheating someone else, he is unaware of the fact that he is the real victim, carefully selected and fatted for the kill. Thus arises the trite but none the less sage maxim: "You can't cheat an honest man."

This fine old principle rules all confidence games, big and little, from a simple three-card monte or shell game in a shady corner of a country fair grounds to the intricate pay-off or rag, played against a big store replete with expensive props and manned by suave experts. The three-card-monte grifter takes a few dollars from a willing farmer here and there; the big-con men take thousands or hundreds of thousands from those who have it. But the principle is always the same.

This accounts for the fact that it has been found very difficult to prosecute confidence men successfully. At the same time it explains why so little of the true nature of confidence games is known to the public, for once a victim is fleeced he often proves to be a most reluctant and untruthful witness against the men who have taken his money. By the same token, confidence men are hardly criminals in the usual sense of the word, for they prosper through a superb knowledge of human nature; they are set apart from those who employ the machine-gun, the blackjack, or the acetylene torch. Their methods differ more in degree than in kind from those employed by more legitimate forms of business.

Modern con men use at present only three big-con games, and only two of these are now used extensively. In addition, there are scores of short-con games which seem to enjoy periodic bursts of activity, followed by alternate periods of obsolescence. Some of these short-con games, when played by big-time professionals who apply the principles of the big con to them, attain very respectable status as devices to separate the mark from his money.

The three big-con games, the wire, the rag, and the pay-off, have in some forty years of their existence taken a staggering toll from a gullible public. No one knows just how much the total is because many touches, especially large ones, never come to light; both con men and police officials agree that roughly ninety per cent of the victims never complain to the police. Some professionals estimate that these three games alone have produced more illicit profit for the operators and for the law than all other forms of professional crime (excepting violations of the prohibition law) over the same period of time. However that may be, it is very certain that they have been immensely profitable.

All confidence games, big and little, have certain similar underlying principles; all of them progress through certain fundamental stages to an inevitable conclusion; while these stages or steps may vary widely in detail from type to type of game, the principles upon which they are based remain the same and are immediately recognizable. In the big-con games the steps are these:

1. Locating and investigating a well-to-do victim. (Putting the mark up.)

2. Gaining the victim's confidence. (Playing the con for him.)

3. Steering him to meet the insideman. (Roping the mark.)

4. Permitting the insideman to show him how he can make a large amount of money dishonestly. (Telling him the tale.)

5. Allowing the victim to make a substantial profit. (Giving him the convincer.)

6. Determining exactly how much he will invest. (Giving him the breakdown.)

7. Sending him home for this amount of money. (Putting him on the send.)

8. Playing him against a big store and fleecing him. (Taking off the touch.)

9. Getting him out of the way as quietly as possible. (Blowing him off.)

10. Forestalling action by the law. (Putting in the fix.)

The big-con games did not spring full-fledged into existence. The principles on which they operate are as old as civilization. But their immediate evolution is closely knit with the invention and development of the big store, a fake gambling club or broker's office, in which the victim is swindled. And within the twentieth century they have, from the criminal's point of view, reached a very high state of perfection.

Descriere

Now back in print--the classic 1940 study of con men and con games that Luc Sante in "Salon" called, "a bonanza of wild but credible stories, told concisely with deadpan humor, as sly and rich in atmosphere as anything this side of Mark Twain."