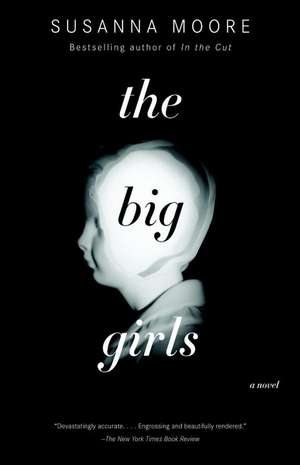

The Big Girls

Autor Susanna Mooreen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2008

Dr. Louise Forrest, a recently divorced mother of an eight-year-old boy, is the new chief of psychiatry there.

Captain Ike Bradshaw is the corrections officer who wants her.

And Angie, an ambitious Hollywood starlet contacted by Helen, is intent on nothing but fame.

Drawing these four characters together in a story of shocking and disturbing revelations, The Big Girls is an electrifying novel about the anarchy of families, the sometimes destructive power of maternal instinct, and the cult of celebrity.

Preț: 88.24 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 132

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.89€ • 17.57$ • 14.15£

16.89€ • 17.57$ • 14.15£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400076109

ISBN-10: 1400076102

Pagini: 224

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: VINTAGE CONTEMPORARIES

ISBN-10: 1400076102

Pagini: 224

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: VINTAGE CONTEMPORARIES

Notă biografică

Susanna Moore is the author of the novels One Last Look, In the Cut, The Whiteness of Bones, Sleeping Beauties, and My Old Sweetheart, which won the Ernest Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award for First Fiction, and the Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Her nonfiction travel book, I Myself Have Seen It, was published by the National Geographic Society in 2003. She lives in New York City.www.susannamoore.com

Extras

Sloatsburg Correctional Institution, a walled complex of seven large stone buildings, sits on the west bank of the Hudson River. An hour north of Manhattan by train, it was built in the late nineteenth century as a sanatorium for tuberculosis patients. Buildings A, B, and C hold five hundred prisoners of the federal government, all of them women. The remaining buildings are used for clinics, schoolrooms, the chapel, and administration as well as for the laundry, kitchens, library, and machine shop. There is a large plot of land behind Building A where the prisoners grow beans. A high brick wall with two wooden watchtowers occupied by men with rifles surrounds the prison on three sides. The river runs parallel to Building C on the east. There are no guardhouses along the river, which causes me to wonder. Do they think that black women can't swim?

My first day at Sloatsburg—six months ago this Monday—I made a cautious tour of the place, looking over my shoulder as if fearful of my own apprehension. No one seemed to notice, or to care, which I decided was a good sign. I am still making a cautious tour of the place.

I enter each weekday morning through elaborate iron gates, left from the days when Sloatsburg's population was consumptive Irish housemaids and dairy farmers, passing slowly through three security checkpoints with cameras, metal detectors, scanning machines, and electronic hand-checks to a large front hall with a white marble floor. The odor, even in the hall, is female.

My office is on the second floor of Building C. The rooms, on either side of a narrow hall, were once used by patients, but now they are occupied by the medical staff and social workers. The doors to the offices, each with a thick glass panel, are often left ajar, and it is possible to overhear the doctors and their patients. Cameras are suspended from the hall ceiling at intervals of thirty feet, although not inside the small bathroom. The bathroom is reserved for staff. The key is one of several we are meant to keep with us at all times, along with keys to the pharmacy, clinic, file room, and chapel, which is kept locked except when it is used as a movie theater.

There are no windows in the offices. There is a wooden desk with drawers. Three metal chairs—the one with arms is for the doctor. I keep my keys in the desk, as well as a Walkman and CDs for the train ride back and forth to the city, a tape measure in a green leather case that once belonged to my mother, a penknife, tea bags, my personal drugs, an alarm clock, a photograph of my son, pens and pencils, a pencil sharpener, and some licorice. Also a flask of vodka and a map of the prison. An electric kettle, teapot, and two Japanese saké cups sit atop a file cabinet. On my desk is a cypripedium in a clay pot. Some of these things are against prison regulations. With a little reflection, I see that my small attempts to make my office more comfortable, more suitable to my tastes, are a bit spinsterish.

Each morning, after checking the pharmacy's compliance sheet (expiration dates of prescriptions), I make a list of the psychiatrists' daily appointments for the officer on duty, who then arranges for the escorts to bring each patient at the appointed time. The most important events of the day are the two counts—one at ten o'clock in the morning and another at four in the afternoon. Because of the counts, there is only time to see two or three patients a day. In the past, patients were treated by a different psychiatrist every other week for two or three minutes. The previous chief of staff was given large amounts of money by the government to conduct a study of the animal tranquilizer ketamine with inmates used as subjects. Ketamine induces, among other things, hallucinations, light trails, and whispering voices. I've canceled the program. If a patient is too psychotic even for us, she is taken under guard to Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan.

I am beginning to understand certain things. Appearances to the contrary, I was a nervous wreck when I arrived last fall. Louise, I would say to myself each morning, you can do this. But the truth is I didn't have a clue. It is a miracle that I've lasted this long. I still feel strained and peculiar—the foul odors, the slow black river, the bells, the yellow light, all swirling around me, make me dizzy. It is only a matter of time.

...

They brought me here right after my sentencing. I was pretty confused. I didn't understand I was going to be locked up for the rest of my life. I thought all along I was going to be put to death. I wanted to be put to death!

The processing took all night. I was with four other women, who I never saw again. We had to fill out a lot of forms. Then they made us take off our clothes, and they searched us like we heard they would, wearing gloves. Some of the officers wore three pairs. They kept yelling, Come on! Come on! Hurry it up, ladies, let's get this show on the road! Which made me even more nervous than I was. One of the other women was crying, and she kept saying, I am innocent, I am innocent, until a guard finally said, Oh, I guess that's why they got you all wrapped up in chains, sweetheart.

I was sweating a lot, and when I was fingerprinted, my thumb came out all blurry. When I apologized, the woman guard taking my prints said in a nice way, It's okay, hon, it's just like the first pancake. The transport officer who had drove the bus was sitting there eating Chinese food and he said, I know what you mean about that pancake. Behind him was a sign, YOU WON'T BE HOME FOR CHRISTMAS.

They asked us to wiggle our toes, pull our ears, and shake our hair, which was hard for the lady with dreads. They told us to puff out our face cheeks and our lips and to hold them that way. They sprayed us for lice and other things. Because it was so late, they decided not to give us a Pap smear and the liver tests. I kept wondering why they were going to so much trouble for people who were on their way to the electric chair, but I didn't say a word.

They put me in a big holding cell with a lot of other prisoners. It was so packed you couldn't lie down, not even on the floor. It was early in the summer, but it was already hot. There was no air-conditioning, and the hum of the generator made me feel calm, like I was inside a big machine. Some people had taken off their tops, wearing them on their head or around their waist. One lady used her bra as a headband. You were supposed to use the intercom to ask for what you needed, like a drink of water or toilet paper, but it didn't work. A lot of the women had their period and there was blood all over them. The toilet was overflowing, stuffed with all kinds of things, not just you-know-what.

They fed us at six-thirty in the morning. Lunch was at eleven, and dinner at four. After about two days—I think it was two days, I had trouble keeping track of time—I was put in my own cell. I was lucky to get moved so quick because some people can stay for weeks until cells are available. I found out later I wasn't even supposed to be with other women, but someone messed up. I was moved in case I was in danger. I felt bad for the ones who got left behind, but I figured they couldn't execute all of us at once. They could only do a few at a time, right? That's what I thought.

...

There are three psychiatrists, in addition to myself, on staff. Dr. Fischl has a full red beard and a medical degree from Grenada. Dr. Henska had her license suspended for six months in 2001 for selling human blood. Dr. de la Vega, if he is in fact a doctor, was engaged by my predecessor, who has since been promoted to Guantánamo Bay, where he advises the government on more efficient ways to increase the psychological and physical duress of prisoners. Dr. de la Vega was found through an agency called Shrinks Only. Each of the doctors, myself included, has eighty patients—at least on paper. We are assisted (impeded) by three medical social workers. Ms. Morton, a case manager, was disciplined in her previous place of employment for the suicide of a twelve-year-old boy in her care. Eight locum tenentes work part-time, usually at night or on the weekend. They tend to be fourth-year psychiatric residents trying to make some money—they can earn six hundred dollars for an eight-hour shift. They have trouble staying awake.

Yesterday, I overheard Dr. Fischl and Dr. de la Vega, who wears black three-piece suits, talking about me—like my former husband, they cannot conceive why I would work in a prison. It's a good question—even I sometimes wonder why I am here. The Girl Scouts, summers with the Haida in Canada, mild lesbian attractions, and a loss of virginity at a rather late age to the regional director of Amnesty International do not in themselves account for it. Dr. Henska and Dr. de la Vega certainly wouldn't work in a prison unless compelled by reasons I hope never to know. No one wants to work as a prison doctor, except the locums. The rest of us are badly paid, although slightly better than the inmates in the psychiatric unit who earn eighteen cents an hour to keep an eye on their fellow inmates. In some institutions, they ask the more melancholy prisoners to sign a pledge that they will not kill themselves. Dr. Henska suggested in a recent staff meeting that we avail ourselves of this precaution. There is not an abundance of wit in these meetings—that would be a lot to ask—but I did think it was funny. Only when she mentioned it a second time did I realize she meant it. I looked my most puzzled, wrinkling my brow to let her know I'd changed my mind—I no longer thought it very funny. Needless to say, she dislikes me.

One hundred African American, Hispanic, and Caucasian men and women are employed by the Bureau of Prisons as corrections officers at Sloatsburg. They aren't particularly friendly to the medical staff, moving as we do between the imprisoned and their captors, and they understandably mistrust us. As do the inmates. Although both the guards and the prisoners find us a bit ridiculous, there is a collective understanding that it does no harm to indulge us. You never know when a doctor might come in handy. The wilier of both groups manipulate us at their pleasure. It is every man for himself. Not the prisoners, but the medical staff.

...

Once I was put in my own cell, they took away the orange jumpsuit I wore in court and gave me two pairs of used jeans, four used black T-shirts in different sizes, black sneakers with elastic sides that fit perfect, three pairs of white tube socks, three pairs of white cotton underpants, two bras, a new blue sweatshirt, and a used black sweater. That's when it began to dawn on me maybe I wasn't going to die. And that's when I REALLY got crazy.

...

My patient Helen appears to be better. Of course, almost anything is an improvement over last month when she was found naked at the door of her cell, shouting Swim away, Ariel! Swim away! Three officers wrapped her in a suicide blanket as heavy as lead and carried her to the psychiatric unit, where she was kept for three weeks. I've had to change her prescription—fifteen milligrams of Haldol with four hundred fifty milligrams of Effexor, three hundred milligrams of Wellbutrin for depression, and a little Cogentin for the side effects of the Haldol. She is back in her own cell in Building C now.

There was some concern when she arrived last summer that her life was in danger, and she was kept in special housing for her own safety. (Last year, an inmate who had watched her husband beat her seven-year-old daughter to death after forcing the child to eat cat food and defecate in kitty litter was found drowned in her toilet bowl.) It eventually became apparent that no one intended to harm Helen, primarily because she was under the protection of an inmate named Wanda, and she was allowed to enter the general population. Her friendship with Wanda makes everything easier for her. I find Wanda a little frightening. I hope that she's not manipulating Helen to use her for illegal commissions. Some of the more aggressive inmates employ the mentally ill and other particularly powerless inmates for criminal purposes, as they aren't unduly punished if caught.

Helen asked me during our session today if I could bring her a subscription form to a handicraft magazine, as she wishes to start thinking about her Christmas gifts. I was sorry to have to refuse, but it is against the rules. She asks for so little, unlike the other women.

...

They make it hard for us prisoners. Not that I have any complaints. It's just not that easy to hide your meds in your mouth when the aide sticks her rubber fingers down your throat three times a day. I broke my glasses last month, but all that got me was three days in Ad Seg. Now they're held together with Snoopy Band-Aids. I still can't have pens, pencils, or a mirror. No hair dryer, wand for heating water, or curling iron for me. Anything with a cord, basically. I can't even have a plastic rosary—I doubt I could hang myself with a rosary. I can't say I blame them.

From the Hardcover edition.

My first day at Sloatsburg—six months ago this Monday—I made a cautious tour of the place, looking over my shoulder as if fearful of my own apprehension. No one seemed to notice, or to care, which I decided was a good sign. I am still making a cautious tour of the place.

I enter each weekday morning through elaborate iron gates, left from the days when Sloatsburg's population was consumptive Irish housemaids and dairy farmers, passing slowly through three security checkpoints with cameras, metal detectors, scanning machines, and electronic hand-checks to a large front hall with a white marble floor. The odor, even in the hall, is female.

My office is on the second floor of Building C. The rooms, on either side of a narrow hall, were once used by patients, but now they are occupied by the medical staff and social workers. The doors to the offices, each with a thick glass panel, are often left ajar, and it is possible to overhear the doctors and their patients. Cameras are suspended from the hall ceiling at intervals of thirty feet, although not inside the small bathroom. The bathroom is reserved for staff. The key is one of several we are meant to keep with us at all times, along with keys to the pharmacy, clinic, file room, and chapel, which is kept locked except when it is used as a movie theater.

There are no windows in the offices. There is a wooden desk with drawers. Three metal chairs—the one with arms is for the doctor. I keep my keys in the desk, as well as a Walkman and CDs for the train ride back and forth to the city, a tape measure in a green leather case that once belonged to my mother, a penknife, tea bags, my personal drugs, an alarm clock, a photograph of my son, pens and pencils, a pencil sharpener, and some licorice. Also a flask of vodka and a map of the prison. An electric kettle, teapot, and two Japanese saké cups sit atop a file cabinet. On my desk is a cypripedium in a clay pot. Some of these things are against prison regulations. With a little reflection, I see that my small attempts to make my office more comfortable, more suitable to my tastes, are a bit spinsterish.

Each morning, after checking the pharmacy's compliance sheet (expiration dates of prescriptions), I make a list of the psychiatrists' daily appointments for the officer on duty, who then arranges for the escorts to bring each patient at the appointed time. The most important events of the day are the two counts—one at ten o'clock in the morning and another at four in the afternoon. Because of the counts, there is only time to see two or three patients a day. In the past, patients were treated by a different psychiatrist every other week for two or three minutes. The previous chief of staff was given large amounts of money by the government to conduct a study of the animal tranquilizer ketamine with inmates used as subjects. Ketamine induces, among other things, hallucinations, light trails, and whispering voices. I've canceled the program. If a patient is too psychotic even for us, she is taken under guard to Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan.

I am beginning to understand certain things. Appearances to the contrary, I was a nervous wreck when I arrived last fall. Louise, I would say to myself each morning, you can do this. But the truth is I didn't have a clue. It is a miracle that I've lasted this long. I still feel strained and peculiar—the foul odors, the slow black river, the bells, the yellow light, all swirling around me, make me dizzy. It is only a matter of time.

...

They brought me here right after my sentencing. I was pretty confused. I didn't understand I was going to be locked up for the rest of my life. I thought all along I was going to be put to death. I wanted to be put to death!

The processing took all night. I was with four other women, who I never saw again. We had to fill out a lot of forms. Then they made us take off our clothes, and they searched us like we heard they would, wearing gloves. Some of the officers wore three pairs. They kept yelling, Come on! Come on! Hurry it up, ladies, let's get this show on the road! Which made me even more nervous than I was. One of the other women was crying, and she kept saying, I am innocent, I am innocent, until a guard finally said, Oh, I guess that's why they got you all wrapped up in chains, sweetheart.

I was sweating a lot, and when I was fingerprinted, my thumb came out all blurry. When I apologized, the woman guard taking my prints said in a nice way, It's okay, hon, it's just like the first pancake. The transport officer who had drove the bus was sitting there eating Chinese food and he said, I know what you mean about that pancake. Behind him was a sign, YOU WON'T BE HOME FOR CHRISTMAS.

They asked us to wiggle our toes, pull our ears, and shake our hair, which was hard for the lady with dreads. They told us to puff out our face cheeks and our lips and to hold them that way. They sprayed us for lice and other things. Because it was so late, they decided not to give us a Pap smear and the liver tests. I kept wondering why they were going to so much trouble for people who were on their way to the electric chair, but I didn't say a word.

They put me in a big holding cell with a lot of other prisoners. It was so packed you couldn't lie down, not even on the floor. It was early in the summer, but it was already hot. There was no air-conditioning, and the hum of the generator made me feel calm, like I was inside a big machine. Some people had taken off their tops, wearing them on their head or around their waist. One lady used her bra as a headband. You were supposed to use the intercom to ask for what you needed, like a drink of water or toilet paper, but it didn't work. A lot of the women had their period and there was blood all over them. The toilet was overflowing, stuffed with all kinds of things, not just you-know-what.

They fed us at six-thirty in the morning. Lunch was at eleven, and dinner at four. After about two days—I think it was two days, I had trouble keeping track of time—I was put in my own cell. I was lucky to get moved so quick because some people can stay for weeks until cells are available. I found out later I wasn't even supposed to be with other women, but someone messed up. I was moved in case I was in danger. I felt bad for the ones who got left behind, but I figured they couldn't execute all of us at once. They could only do a few at a time, right? That's what I thought.

...

There are three psychiatrists, in addition to myself, on staff. Dr. Fischl has a full red beard and a medical degree from Grenada. Dr. Henska had her license suspended for six months in 2001 for selling human blood. Dr. de la Vega, if he is in fact a doctor, was engaged by my predecessor, who has since been promoted to Guantánamo Bay, where he advises the government on more efficient ways to increase the psychological and physical duress of prisoners. Dr. de la Vega was found through an agency called Shrinks Only. Each of the doctors, myself included, has eighty patients—at least on paper. We are assisted (impeded) by three medical social workers. Ms. Morton, a case manager, was disciplined in her previous place of employment for the suicide of a twelve-year-old boy in her care. Eight locum tenentes work part-time, usually at night or on the weekend. They tend to be fourth-year psychiatric residents trying to make some money—they can earn six hundred dollars for an eight-hour shift. They have trouble staying awake.

Yesterday, I overheard Dr. Fischl and Dr. de la Vega, who wears black three-piece suits, talking about me—like my former husband, they cannot conceive why I would work in a prison. It's a good question—even I sometimes wonder why I am here. The Girl Scouts, summers with the Haida in Canada, mild lesbian attractions, and a loss of virginity at a rather late age to the regional director of Amnesty International do not in themselves account for it. Dr. Henska and Dr. de la Vega certainly wouldn't work in a prison unless compelled by reasons I hope never to know. No one wants to work as a prison doctor, except the locums. The rest of us are badly paid, although slightly better than the inmates in the psychiatric unit who earn eighteen cents an hour to keep an eye on their fellow inmates. In some institutions, they ask the more melancholy prisoners to sign a pledge that they will not kill themselves. Dr. Henska suggested in a recent staff meeting that we avail ourselves of this precaution. There is not an abundance of wit in these meetings—that would be a lot to ask—but I did think it was funny. Only when she mentioned it a second time did I realize she meant it. I looked my most puzzled, wrinkling my brow to let her know I'd changed my mind—I no longer thought it very funny. Needless to say, she dislikes me.

One hundred African American, Hispanic, and Caucasian men and women are employed by the Bureau of Prisons as corrections officers at Sloatsburg. They aren't particularly friendly to the medical staff, moving as we do between the imprisoned and their captors, and they understandably mistrust us. As do the inmates. Although both the guards and the prisoners find us a bit ridiculous, there is a collective understanding that it does no harm to indulge us. You never know when a doctor might come in handy. The wilier of both groups manipulate us at their pleasure. It is every man for himself. Not the prisoners, but the medical staff.

...

Once I was put in my own cell, they took away the orange jumpsuit I wore in court and gave me two pairs of used jeans, four used black T-shirts in different sizes, black sneakers with elastic sides that fit perfect, three pairs of white tube socks, three pairs of white cotton underpants, two bras, a new blue sweatshirt, and a used black sweater. That's when it began to dawn on me maybe I wasn't going to die. And that's when I REALLY got crazy.

...

My patient Helen appears to be better. Of course, almost anything is an improvement over last month when she was found naked at the door of her cell, shouting Swim away, Ariel! Swim away! Three officers wrapped her in a suicide blanket as heavy as lead and carried her to the psychiatric unit, where she was kept for three weeks. I've had to change her prescription—fifteen milligrams of Haldol with four hundred fifty milligrams of Effexor, three hundred milligrams of Wellbutrin for depression, and a little Cogentin for the side effects of the Haldol. She is back in her own cell in Building C now.

There was some concern when she arrived last summer that her life was in danger, and she was kept in special housing for her own safety. (Last year, an inmate who had watched her husband beat her seven-year-old daughter to death after forcing the child to eat cat food and defecate in kitty litter was found drowned in her toilet bowl.) It eventually became apparent that no one intended to harm Helen, primarily because she was under the protection of an inmate named Wanda, and she was allowed to enter the general population. Her friendship with Wanda makes everything easier for her. I find Wanda a little frightening. I hope that she's not manipulating Helen to use her for illegal commissions. Some of the more aggressive inmates employ the mentally ill and other particularly powerless inmates for criminal purposes, as they aren't unduly punished if caught.

Helen asked me during our session today if I could bring her a subscription form to a handicraft magazine, as she wishes to start thinking about her Christmas gifts. I was sorry to have to refuse, but it is against the rules. She asks for so little, unlike the other women.

...

They make it hard for us prisoners. Not that I have any complaints. It's just not that easy to hide your meds in your mouth when the aide sticks her rubber fingers down your throat three times a day. I broke my glasses last month, but all that got me was three days in Ad Seg. Now they're held together with Snoopy Band-Aids. I still can't have pens, pencils, or a mirror. No hair dryer, wand for heating water, or curling iron for me. Anything with a cord, basically. I can't even have a plastic rosary—I doubt I could hang myself with a rosary. I can't say I blame them.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"Devastatingly accurate.... Engrossing and beautifully rendered.” —The New York Times Book Review“The most unflinching, graphically sexual, violent, literary female fiction writer alive. . . . Susanna Moore writes the way Frida Kahlo painted.” —Los Angeles Times Book Review“The Big Girls carries a voyeuristic charge, the confessions so intimate you feel embarrassed for looking, but the whip-smart narration makes it impossible to turn away.” —The Plain Dealer “Hypnotizing. . . . A remarkable feat.” —The Washington Post Book World

Descriere

From the bestselling author of "In the Cut" comes an electrifying novel about the anarchy of families, the sometimes destructive power of material instinct, and the cult of celebrity.