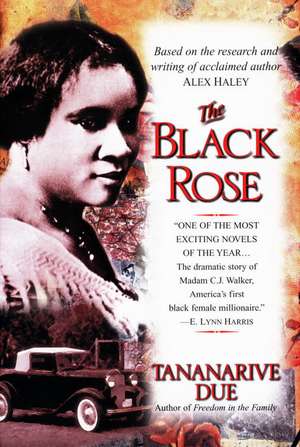

The Black Rose

Autor Tananarive Dueen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2000

Blending documented history, vivid dialogue, and a sweeping fictionalized narrative, Tananarive Due paints a vivid portrait of this passionate and tenacious pioneer and the unforgettable era in which she lived.

Preț: 144.11 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 216

Preț estimativ în valută:

27.58€ • 28.69$ • 22.77£

27.58€ • 28.69$ • 22.77£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345441560

ISBN-10: 0345441567

Pagini: 384

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Editura: One World/Ballantine

ISBN-10: 0345441567

Pagini: 384

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Editura: One World/Ballantine

Notă biografică

Tananarive Due is a former features writer and columnist for the Miami Herald. She has written two highly acclaimed novels: The Between and My Soul to Keep. Ms. Due makes her home in Longview, Washington.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter One

Delta, Louisiana

Spring 1874

The slave-kitchers couldn't get her. Not so long as she stayed hid.

Stealthily, Sarah crouched her small frame behind the thick tangle of tall

grass that pricked through the thin fabric of her dress, which was so worn

at the hem that it had frayed into feathery threads that tickled her shins.

"Sarah, where you at?"

Sarah felt her heart leap when she heard the dreaded voice so close

to her. That was the meanest, most devilish slave-kitcher of all, the one

called Terrible Lou the Wicked. If Terrible Lou the Wicked caught her,

Sarah knew she'd be sold west to the Indians for sure and she'd never see

her family again. Sarah tried to slow her breathing so she could be quiet

as a skulking cat. The brush near her stirred as Terrible Lou barreled

through, searching for her. Sweat trickled into Sarah's eye, but she

didn't move even to rub out the sting.

"See, I done tol' Mama 'bout how you do. Ain't nobody playin' no games

with you! I'ma find you, watch. And when I do, I'ma break me off a switch,

an' you better not holler."

A whipping! Sarah had heard Terrible Lou whipped little children half to

death just for the fun of it, even babies. Sarah was more determined than

ever not to be caught. If Terrible Lou found her, Sarah decided she'd jump

out and wrastle her to the ground. Sarah crouched closer to the ground,

ready to spring. She felt her heart going boom-boom boom-boom deep in her

chest. "Ain't no slave-kitcher takin' me!" Sarah yelled out, daring

Terrible Lou.

"Yes, one is, too," Terrible Lou said, the voice suddenly much closer.

"I'ma cut you up an' sell you in bits if you don't come an' git back to

work."

Sarah saw her sister Louvenia's plaited head appear right in front of her,

her teeth drawn back into a snarl, and she screamed. Louvenia was too big

to wrastle! Screaming again, Sarah took off running in the high grass, and

she could feel her sister's heels right behind her step for step. Louvenia

was laughing, and soon Sarah was laughing, too, even though it made her

lungs hurt because she was running so hard.

"You always playin' some game! Well, I'ma catch you, too. How come you so

slow?" Louvenia said, forcing the words through her hard breaths, her legs

pumping.

"How come you so ugly?" Sarah taunted, and shrieked again as Louvenia's

arm lunged toward her, brushing the back of her dress. Sarah barely darted

free with a spurt of speed.

"You gon' be pickin' rice 'til you fall an' drown in them rice fields

downriver."

"No, I ain't neither! You the one gon' drown," Sarah said.

"You the one can't swim good."

"Can, too! Better'n you." By now, Sarah was nearly gasping from the effort

of running as she climbed the knoll behind their house. Louvenia lunged

after her legs, and they both tumbled into the overgrown crabgrass. They

swatted at each other playfully, and Sarah tried to wriggle away, but

Louvenia held her firmly around her waist.

"See, you caught now!" Louvenia said breathlessly. "I'ma sell you for a

half dollar."

"A half dollar!" Sarah said, insulted. She gave up her struggle against

her older sister's tight grip. Louvenia's arms, it seemed to her, were as

strong as a man's. "What you mean? Papa paid a dollar for his new boots!"

Louvenia grinned wickedly. "That's right. You ain't even worth one of

Papa's boots, lazy as you is."

"There Papa go now. I'ma ask him what he say I'm worth," Sarah teased, and

Louvenia glanced around anxiously for Papa. If Papa saw Louvenia pinning

Sarah to the ground, Sarah knew he'd whip Louvenia for sure. Louvenia and

Alex weren't allowed to play rough with Sarah. That was Papa's law,

because she was the baby. And she'd been born two days before Christmas,

Sarah liked to remind Louvenia, so she was close to baby Jesus besides.

"You done it agin, Sarah. Got me playin'," Louvenia complained, satisfied

that Papa was nowhere near after peering toward the dirt road and dozens

of acres of cotton fields that had been planted in March and April,

sprouting with plants and troublesome grass and weeds. Still, her voice

was much more hushed than it had been before. "You always gittin' somebody

in trouble."

"I ain't tell you to chase me. An' I ain't tell you to stop workin'."

"Sarah, see, you think we jus' out here playin', but then I'm the one got

to answer why we ain't finish yet."

Seeing Louvenia's earnest brown eyes, Sarah knew for the first time that

her sister had lost the heart to pretend she was a slave-kitcher, or for

any games at all. Right now, Louvenia's face looked as solemn as Mama's or

Papa's when the cotton yields were poor or when their house was too cold.

And Louvenia was right, Sarah knew. Just a few days before, Louvenia had

been whipped when they broke one of the eggs they'd been gathering in the

henhouse. It had been Lou's idea to break up the boredom of the task by

tossing the eggs to each other standing farther and farther away. They

broke an egg by the time they were through, and Sarah hadn't seen Mama

that mad in a long time. "Girl, you ten years old, almost grown!" Mama had

said, thrashing Louvenia's bottom with a thin branch from the sassafras

tree near their front door. "That baby ain't s'posed to be lookin' after

you! When you gon' get some head sense?"

Louvenia's eyes, to Sarah, looked sad and even a little scared. Maybe she

was remembering her thrashing, too. Sarah didn't want her sister to feel

cross with her, because Louvenia was her only playmate. In fact, although

Sarah would never want to admit it to her, Louvenia was her best friend,

her most favorite person. Next to Papa and Mama, of course.

Sarah squeezed Lou's hand. "Come on, I'll help. We won't play no mo' 'til

we done."

"We ain't gon' be done 'fore Papa and them come back."

"Yeah, we will, too," Sarah said. "If we sing."

That made Louvenia smile. She liked to sing, and Papa had taught them

songs he learned from his pappy when he was a boy on a big plan-

tation he said had a hundred slaves. Sarah couldn't sing as well as her

sister--her voice wouldn't always do what she told it to--but singing always

made work go by faster. Mama sang, too, when the womenfolk came on

Saturdays to wash laundry with them on the riverbank. But Papa had the

best voice of all. Papa sang when he was picking, and to Sarah his voice

was as deep and pretty as the Mississippi River on a full-moon night. Papa

always started singing when he was tired, and Sarah liked to watch him

pick up his broad shoulders each time he took a breath before singing a

new verse, as if the song was making him stronger:

O me no weary yet,

O me no weary yet.

I have a witness in my heart,

O me no weary yet.

Sarah and Louvenia enjoyed the uplifting messages in Mama's and Papa's

songs, which were mostly about Jesus, heaven, and Gabriel's trumpet, but

they also liked the sillier songs Mama didn't approve of, the ones Papa

sang on Saturday nights after he'd had a drink from the jug he kept hidden

behind the old cracked wagon wheel that leaned against their cabin. Sarah

and Louvenia thought those songs were funny, so that was what they sang

that afternoon as they crouched to chop weeds from Mama's garden:

Hi-ho, for Charleston gals!

Charleston gals are the gals for me.

As I went a-walking down the street,

Up steps Charleston gals to take a walk with me.

I kep' a-walking and they kep' a-talking,

I danced with a gal with a hole in her stocking.

Together, as Sarah and her sister yanked up the stubborn weeds that grew

frustratingly fast around Mama's rows of green beans, potatoes, and yams,

they sang their father's old songs. Finally, the boredom that had felt

like it was choking Sarah all day long in the hot sun finally let her mind

alone. Instead of fantasizing about slave-kitchers Papa had told them

so many stories about, or fishing for catfish, or the peppermint sticks at

the general store in town she was allowed to eat at Christmastime, Sarah

thought only of her task. Her hands seemed to fly. She'd chop the soil to

loosen it with the rusted old hatchet Papa let her use, then pull up the

weeds by the roots so they wouldn't come back. Chop and pull, chop and

pull. Sarah didn't stop working even when the rows of calluses on her

small hands began to throb in rhythm with her chopping. By the time they

saw Mama's kerchief bobbing toward the house in the distance, followed by

Papa's wide-brim hat, their weeding was finished, and they were lying on

their backs in the crabgrass behind their house, arguing over what shapes

they could see in the ghostly moon that was just beginning to make itself

visible in a corner of the late-afternoon sky.

The cabin's windows, which were pasted shut with paper instead of glass

during cooler months, were a curse in the winter, since they were little

protection against the biting cold even with the shutters tied shut. But

now, in spring, when the bare windows should have been inviting in a cool

twilight breeze, the air inside the cabin was so still, so stiff and hot

that Sarah hated to breathe it. It felt to her like hot air was trapped in

the wooden walls, in the loose floorboards, in every crooked shingle on

the drafty roof. Sarah watched the sunlight creeping through the slatted

cracks in the walls and ceiling where the mud needed patching, wishing

dark would hurry up and come and make it cool. Hungry as she was, Sarah

wished Mama didn't have the cookstove lit, because it only made the cabin

hotter. And it wasn't even summertime yet, Sarah thought sadly. By summer

the heat would be worse, and the sun would bring out the cotton they would

have to pick come the first of September.

Papa swatted at the big green flies and skeeters hovering above

the table. Mosquitoes always seemed to know when it was suppertime, Sarah

thought. Papa's arm moved lazily in front of his face as he shooed the

insects, as if he were hunched over the table asleep. Sarah knew better

than to try to talk to Papa too soon after he'd come back from the fields,

especially close to June. Sarah and Louvenia were both too small to help

in the fields in late May, because that was when Papa, Mama, and Alex

pushed plows to break up acre after acre of soil to tend the cotton plants

properly. Sarah and Louvenia did weeding, or on some days carried water

and corncakes out to the croppers. Papa hated plowing those deep furrows

between the rows, and Sarah could see how much he hated it in the lines on

his frowning, sunbaked face as he sat

at the table. Papa and Alex were barebacked, so slick with sweat they

looked greased up.

Papa and Alex spoke to each other with short grunts and words uttered so

low Sarah couldn't make out what they were saying, man-talking that came

from deep in their throats. She'd heard men speak that way to each other

in the fields, or as they rested on the front stoop and shared a jug and

rumbles of laughter. Papa grunted something, and Alex smiled, muttering

husky words back. Sarah knew her brother was nearly a man now, and she'd

seen the change in the way Papa treated him. It was the same way Mama was

treating Louvenia like a grown woman, expecting her to cook and mend and

do a bigger share of fieldwork. Everyone was grown-up except her.

Sarah knew she could go to her pallet and play with the doll Papa had made

her out of cornhusks wrapped together with twine, but she wanted

to be more grown-up than that. She walked across the cabin--she counted

twenty paces to get from one side to the other; she'd learned numbers up

to twenty from Papa--and stood by the cookstove on her tiptoes to watch

Mama stir collard greens in her big saucepan while Louvenia sat on the

floor and mended a tear in her dress. Mama had one kerchief on her head

and one knotted around her neck, both of them gray from grime. Her cheeks

were full, and she had a youthful, pretty face; skin black as midnight and

smooth like an Indian squaw's, Papa always said. Gazing at her, Sarah

wondered if her mother would ever become stooped-over and sour-faced like

so many other women she had seen in the fields.

Sarah expected Mama to tell her to get from underfoot, but she didn't.

Instead she gave Sarah a big, steaming bowl. "Pass yo' papa his supper,"

Mama told her, and Sarah grinned. The smell of the greens, yams, and corn

bread made her stomach flip from hunger. Papa's eyes didn't smile when he

took his food from Sarah, but he did squeeze her fingers. Sarah knew that

was his special way of saying Thank you, Li'l Bit.

Outside, Papa's hound barked loudly, and Papa and Alex looked up

at the same instant. They all heard the whinny of a horse and a heavy

clop-clopping sound that signaled the arrival of not one horse, but two or

more. An approaching wagon scraped loudly in the dirt.

"Who'n de world . . . ?" Mama said, leaning toward the window.

"Not-uh," Papa warned her, standing tall so quickly that his chair

screeched on the hard packed-dirt floor. "Don' put your head out. Git

back." Something in Papa's voice that Sarah couldn't quite name made her

stomach fall silent, and it seemed to harden to stone. His voice was

dangerous, wound tight, and Sarah didn't know where that new quality had

come from so suddenly. She had never heard Papa sound that way before.

Silently, Mama took Sarah's hand and pulled her back toward the stove at

the rear of the cabin. Louvenia was still sitting on the floor, but her

hands were frozen with her thread and needle in midair. Alex stood up at

the table while Papa took long strides to the doorway, where he stood with

his arms folded across his chest.

"Whoa there!" a man's voice outside snapped to his horses. It sounded like

a white man. Sarah felt her mother's grip tighten around her fingers, her

face drawn with concern.

Papa's whole demeanor changed; the shoulders that had been thrust so high

suddenly fell, as if he had exhaled all his breath. He shifted his weight,

no longer blocking the light from the doorway. The dangerous stance had

vanished. "Evenin', Missus," Papa said, nearly mumbling.

"Evening, Owen," a woman's voice said.

A frightening thought came to Sarah: I hope they ain't here to take our

house away. She didn't know why the visitors would do something like that,

but she did know that she'd heard Mama and Papa talking about their

payment being late. And she knew that their house, like everything

else--including the land as far as they could see, Papa's tools, their

cottonseed, and even the straw pallets they slept on--belonged to the

Burney daughters. Time was, before 'Man-ci-pa-tion and the war that ended

two years before Sarah was born, and before Ole Marster and Ole Missus

died in '66 ("Of heartbreak," Mama always said, because of their land

being overrun by Yankees and their crops and buildings burned up), the

Burneys owned Mama and Papa and a lot of other slaves besides. Some of

those slaves, like Mama and Papa, still worked on the land as croppers.

But some of the other slaves, Mama told her, were so happy to be free that

they'd just left.

Where'd they go? Sarah had asked, full of wonder at the notion that

the other freed slaves had crossed the bridge to go to Vicksburg, or even

beyond. The only other places she knew about were Mississippi and

Charleston, like in the song. Had they gone away on a steamship? On a

train?

They went on they own feets, pullin' every scrap they owned on wagons,

Mama said. And Lord only know where they at now. Might wish they was back

here. Now Sarah had a bad feeling. She wondered why Mama and Papa hadn't

pulled a wagon with every scrap they owned and left on their own feet

after freedom came, too. If they had, they wouldn't be late on their

payment, and these white folks wouldn't be coming to take their house.

Delta, Louisiana

Spring 1874

The slave-kitchers couldn't get her. Not so long as she stayed hid.

Stealthily, Sarah crouched her small frame behind the thick tangle of tall

grass that pricked through the thin fabric of her dress, which was so worn

at the hem that it had frayed into feathery threads that tickled her shins.

"Sarah, where you at?"

Sarah felt her heart leap when she heard the dreaded voice so close

to her. That was the meanest, most devilish slave-kitcher of all, the one

called Terrible Lou the Wicked. If Terrible Lou the Wicked caught her,

Sarah knew she'd be sold west to the Indians for sure and she'd never see

her family again. Sarah tried to slow her breathing so she could be quiet

as a skulking cat. The brush near her stirred as Terrible Lou barreled

through, searching for her. Sweat trickled into Sarah's eye, but she

didn't move even to rub out the sting.

"See, I done tol' Mama 'bout how you do. Ain't nobody playin' no games

with you! I'ma find you, watch. And when I do, I'ma break me off a switch,

an' you better not holler."

A whipping! Sarah had heard Terrible Lou whipped little children half to

death just for the fun of it, even babies. Sarah was more determined than

ever not to be caught. If Terrible Lou found her, Sarah decided she'd jump

out and wrastle her to the ground. Sarah crouched closer to the ground,

ready to spring. She felt her heart going boom-boom boom-boom deep in her

chest. "Ain't no slave-kitcher takin' me!" Sarah yelled out, daring

Terrible Lou.

"Yes, one is, too," Terrible Lou said, the voice suddenly much closer.

"I'ma cut you up an' sell you in bits if you don't come an' git back to

work."

Sarah saw her sister Louvenia's plaited head appear right in front of her,

her teeth drawn back into a snarl, and she screamed. Louvenia was too big

to wrastle! Screaming again, Sarah took off running in the high grass, and

she could feel her sister's heels right behind her step for step. Louvenia

was laughing, and soon Sarah was laughing, too, even though it made her

lungs hurt because she was running so hard.

"You always playin' some game! Well, I'ma catch you, too. How come you so

slow?" Louvenia said, forcing the words through her hard breaths, her legs

pumping.

"How come you so ugly?" Sarah taunted, and shrieked again as Louvenia's

arm lunged toward her, brushing the back of her dress. Sarah barely darted

free with a spurt of speed.

"You gon' be pickin' rice 'til you fall an' drown in them rice fields

downriver."

"No, I ain't neither! You the one gon' drown," Sarah said.

"You the one can't swim good."

"Can, too! Better'n you." By now, Sarah was nearly gasping from the effort

of running as she climbed the knoll behind their house. Louvenia lunged

after her legs, and they both tumbled into the overgrown crabgrass. They

swatted at each other playfully, and Sarah tried to wriggle away, but

Louvenia held her firmly around her waist.

"See, you caught now!" Louvenia said breathlessly. "I'ma sell you for a

half dollar."

"A half dollar!" Sarah said, insulted. She gave up her struggle against

her older sister's tight grip. Louvenia's arms, it seemed to her, were as

strong as a man's. "What you mean? Papa paid a dollar for his new boots!"

Louvenia grinned wickedly. "That's right. You ain't even worth one of

Papa's boots, lazy as you is."

"There Papa go now. I'ma ask him what he say I'm worth," Sarah teased, and

Louvenia glanced around anxiously for Papa. If Papa saw Louvenia pinning

Sarah to the ground, Sarah knew he'd whip Louvenia for sure. Louvenia and

Alex weren't allowed to play rough with Sarah. That was Papa's law,

because she was the baby. And she'd been born two days before Christmas,

Sarah liked to remind Louvenia, so she was close to baby Jesus besides.

"You done it agin, Sarah. Got me playin'," Louvenia complained, satisfied

that Papa was nowhere near after peering toward the dirt road and dozens

of acres of cotton fields that had been planted in March and April,

sprouting with plants and troublesome grass and weeds. Still, her voice

was much more hushed than it had been before. "You always gittin' somebody

in trouble."

"I ain't tell you to chase me. An' I ain't tell you to stop workin'."

"Sarah, see, you think we jus' out here playin', but then I'm the one got

to answer why we ain't finish yet."

Seeing Louvenia's earnest brown eyes, Sarah knew for the first time that

her sister had lost the heart to pretend she was a slave-kitcher, or for

any games at all. Right now, Louvenia's face looked as solemn as Mama's or

Papa's when the cotton yields were poor or when their house was too cold.

And Louvenia was right, Sarah knew. Just a few days before, Louvenia had

been whipped when they broke one of the eggs they'd been gathering in the

henhouse. It had been Lou's idea to break up the boredom of the task by

tossing the eggs to each other standing farther and farther away. They

broke an egg by the time they were through, and Sarah hadn't seen Mama

that mad in a long time. "Girl, you ten years old, almost grown!" Mama had

said, thrashing Louvenia's bottom with a thin branch from the sassafras

tree near their front door. "That baby ain't s'posed to be lookin' after

you! When you gon' get some head sense?"

Louvenia's eyes, to Sarah, looked sad and even a little scared. Maybe she

was remembering her thrashing, too. Sarah didn't want her sister to feel

cross with her, because Louvenia was her only playmate. In fact, although

Sarah would never want to admit it to her, Louvenia was her best friend,

her most favorite person. Next to Papa and Mama, of course.

Sarah squeezed Lou's hand. "Come on, I'll help. We won't play no mo' 'til

we done."

"We ain't gon' be done 'fore Papa and them come back."

"Yeah, we will, too," Sarah said. "If we sing."

That made Louvenia smile. She liked to sing, and Papa had taught them

songs he learned from his pappy when he was a boy on a big plan-

tation he said had a hundred slaves. Sarah couldn't sing as well as her

sister--her voice wouldn't always do what she told it to--but singing always

made work go by faster. Mama sang, too, when the womenfolk came on

Saturdays to wash laundry with them on the riverbank. But Papa had the

best voice of all. Papa sang when he was picking, and to Sarah his voice

was as deep and pretty as the Mississippi River on a full-moon night. Papa

always started singing when he was tired, and Sarah liked to watch him

pick up his broad shoulders each time he took a breath before singing a

new verse, as if the song was making him stronger:

O me no weary yet,

O me no weary yet.

I have a witness in my heart,

O me no weary yet.

Sarah and Louvenia enjoyed the uplifting messages in Mama's and Papa's

songs, which were mostly about Jesus, heaven, and Gabriel's trumpet, but

they also liked the sillier songs Mama didn't approve of, the ones Papa

sang on Saturday nights after he'd had a drink from the jug he kept hidden

behind the old cracked wagon wheel that leaned against their cabin. Sarah

and Louvenia thought those songs were funny, so that was what they sang

that afternoon as they crouched to chop weeds from Mama's garden:

Hi-ho, for Charleston gals!

Charleston gals are the gals for me.

As I went a-walking down the street,

Up steps Charleston gals to take a walk with me.

I kep' a-walking and they kep' a-talking,

I danced with a gal with a hole in her stocking.

Together, as Sarah and her sister yanked up the stubborn weeds that grew

frustratingly fast around Mama's rows of green beans, potatoes, and yams,

they sang their father's old songs. Finally, the boredom that had felt

like it was choking Sarah all day long in the hot sun finally let her mind

alone. Instead of fantasizing about slave-kitchers Papa had told them

so many stories about, or fishing for catfish, or the peppermint sticks at

the general store in town she was allowed to eat at Christmastime, Sarah

thought only of her task. Her hands seemed to fly. She'd chop the soil to

loosen it with the rusted old hatchet Papa let her use, then pull up the

weeds by the roots so they wouldn't come back. Chop and pull, chop and

pull. Sarah didn't stop working even when the rows of calluses on her

small hands began to throb in rhythm with her chopping. By the time they

saw Mama's kerchief bobbing toward the house in the distance, followed by

Papa's wide-brim hat, their weeding was finished, and they were lying on

their backs in the crabgrass behind their house, arguing over what shapes

they could see in the ghostly moon that was just beginning to make itself

visible in a corner of the late-afternoon sky.

The cabin's windows, which were pasted shut with paper instead of glass

during cooler months, were a curse in the winter, since they were little

protection against the biting cold even with the shutters tied shut. But

now, in spring, when the bare windows should have been inviting in a cool

twilight breeze, the air inside the cabin was so still, so stiff and hot

that Sarah hated to breathe it. It felt to her like hot air was trapped in

the wooden walls, in the loose floorboards, in every crooked shingle on

the drafty roof. Sarah watched the sunlight creeping through the slatted

cracks in the walls and ceiling where the mud needed patching, wishing

dark would hurry up and come and make it cool. Hungry as she was, Sarah

wished Mama didn't have the cookstove lit, because it only made the cabin

hotter. And it wasn't even summertime yet, Sarah thought sadly. By summer

the heat would be worse, and the sun would bring out the cotton they would

have to pick come the first of September.

Papa swatted at the big green flies and skeeters hovering above

the table. Mosquitoes always seemed to know when it was suppertime, Sarah

thought. Papa's arm moved lazily in front of his face as he shooed the

insects, as if he were hunched over the table asleep. Sarah knew better

than to try to talk to Papa too soon after he'd come back from the fields,

especially close to June. Sarah and Louvenia were both too small to help

in the fields in late May, because that was when Papa, Mama, and Alex

pushed plows to break up acre after acre of soil to tend the cotton plants

properly. Sarah and Louvenia did weeding, or on some days carried water

and corncakes out to the croppers. Papa hated plowing those deep furrows

between the rows, and Sarah could see how much he hated it in the lines on

his frowning, sunbaked face as he sat

at the table. Papa and Alex were barebacked, so slick with sweat they

looked greased up.

Papa and Alex spoke to each other with short grunts and words uttered so

low Sarah couldn't make out what they were saying, man-talking that came

from deep in their throats. She'd heard men speak that way to each other

in the fields, or as they rested on the front stoop and shared a jug and

rumbles of laughter. Papa grunted something, and Alex smiled, muttering

husky words back. Sarah knew her brother was nearly a man now, and she'd

seen the change in the way Papa treated him. It was the same way Mama was

treating Louvenia like a grown woman, expecting her to cook and mend and

do a bigger share of fieldwork. Everyone was grown-up except her.

Sarah knew she could go to her pallet and play with the doll Papa had made

her out of cornhusks wrapped together with twine, but she wanted

to be more grown-up than that. She walked across the cabin--she counted

twenty paces to get from one side to the other; she'd learned numbers up

to twenty from Papa--and stood by the cookstove on her tiptoes to watch

Mama stir collard greens in her big saucepan while Louvenia sat on the

floor and mended a tear in her dress. Mama had one kerchief on her head

and one knotted around her neck, both of them gray from grime. Her cheeks

were full, and she had a youthful, pretty face; skin black as midnight and

smooth like an Indian squaw's, Papa always said. Gazing at her, Sarah

wondered if her mother would ever become stooped-over and sour-faced like

so many other women she had seen in the fields.

Sarah expected Mama to tell her to get from underfoot, but she didn't.

Instead she gave Sarah a big, steaming bowl. "Pass yo' papa his supper,"

Mama told her, and Sarah grinned. The smell of the greens, yams, and corn

bread made her stomach flip from hunger. Papa's eyes didn't smile when he

took his food from Sarah, but he did squeeze her fingers. Sarah knew that

was his special way of saying Thank you, Li'l Bit.

Outside, Papa's hound barked loudly, and Papa and Alex looked up

at the same instant. They all heard the whinny of a horse and a heavy

clop-clopping sound that signaled the arrival of not one horse, but two or

more. An approaching wagon scraped loudly in the dirt.

"Who'n de world . . . ?" Mama said, leaning toward the window.

"Not-uh," Papa warned her, standing tall so quickly that his chair

screeched on the hard packed-dirt floor. "Don' put your head out. Git

back." Something in Papa's voice that Sarah couldn't quite name made her

stomach fall silent, and it seemed to harden to stone. His voice was

dangerous, wound tight, and Sarah didn't know where that new quality had

come from so suddenly. She had never heard Papa sound that way before.

Silently, Mama took Sarah's hand and pulled her back toward the stove at

the rear of the cabin. Louvenia was still sitting on the floor, but her

hands were frozen with her thread and needle in midair. Alex stood up at

the table while Papa took long strides to the doorway, where he stood with

his arms folded across his chest.

"Whoa there!" a man's voice outside snapped to his horses. It sounded like

a white man. Sarah felt her mother's grip tighten around her fingers, her

face drawn with concern.

Papa's whole demeanor changed; the shoulders that had been thrust so high

suddenly fell, as if he had exhaled all his breath. He shifted his weight,

no longer blocking the light from the doorway. The dangerous stance had

vanished. "Evenin', Missus," Papa said, nearly mumbling.

"Evening, Owen," a woman's voice said.

A frightening thought came to Sarah: I hope they ain't here to take our

house away. She didn't know why the visitors would do something like that,

but she did know that she'd heard Mama and Papa talking about their

payment being late. And she knew that their house, like everything

else--including the land as far as they could see, Papa's tools, their

cottonseed, and even the straw pallets they slept on--belonged to the

Burney daughters. Time was, before 'Man-ci-pa-tion and the war that ended

two years before Sarah was born, and before Ole Marster and Ole Missus

died in '66 ("Of heartbreak," Mama always said, because of their land

being overrun by Yankees and their crops and buildings burned up), the

Burneys owned Mama and Papa and a lot of other slaves besides. Some of

those slaves, like Mama and Papa, still worked on the land as croppers.

But some of the other slaves, Mama told her, were so happy to be free that

they'd just left.

Where'd they go? Sarah had asked, full of wonder at the notion that

the other freed slaves had crossed the bridge to go to Vicksburg, or even

beyond. The only other places she knew about were Mississippi and

Charleston, like in the song. Had they gone away on a steamship? On a

train?

They went on they own feets, pullin' every scrap they owned on wagons,

Mama said. And Lord only know where they at now. Might wish they was back

here. Now Sarah had a bad feeling. She wondered why Mama and Papa hadn't

pulled a wagon with every scrap they owned and left on their own feet

after freedom came, too. If they had, they wouldn't be late on their

payment, and these white folks wouldn't be coming to take their house.

Recenzii

"TANANARIVE DUE IS AN ENGAGING STORYTELLER . . . The real-life Walker would probably have been pleased with the way Due depicts her. . . . The Black Rose is an inspiring, motivational book."

--The Washington Post Book World

"A COMPELLING NARRATIVE . . . This book is worth reading for anyone wanting a glimpse into what the human spirit can create with the odds stacked sky high."

--USA Today

--The Washington Post Book World

"A COMPELLING NARRATIVE . . . This book is worth reading for anyone wanting a glimpse into what the human spirit can create with the odds stacked sky high."

--USA Today

Descriere

This fictional account of a true story, based on the research and writings of Alex Haley, begins in 1867, when Madame C.J. Walker is born to former slaves on a Louisiana plantation. The story of how she rises from poverty and indignity to become America's first black female millionaire is told in this compelling, richly textured narrative.