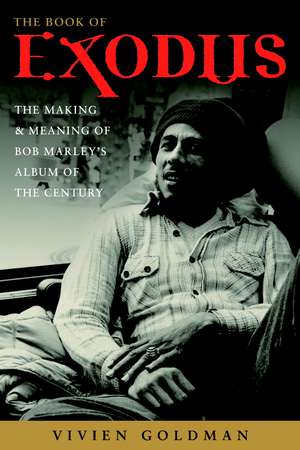

The Book of Exodus: The Making and Meaning of Bob Marley and the Wailers' Album of the Century

Autor Vivien Goldmanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2006

Bob Marley is one of our most important and influential artists. Recorded in London after an assassination attempt on his life sent Marley into exile from Jamaica, Exodus is the most lasting testament to his social conscience. Named by Time magazine as “Album of the Century,” Exodus is reggae superstar Bob Marley’s masterpiece of spiritual exploration.

Vivien Goldman was the first journalist to introduce mass white audiences to the Rasta sounds of Bob Marley. Throughout the late 1970s, Goldman was a fly on the wall as she watched reggae grow and evolve, and charted the careers of many of its superstars, especially Bob Marley. So close was Vivien to Bob and the Wailers that she was a guest at his Kingston home just days before gunmen came in a rush to kill “The Skip.” Now, in The Book of Exodus, Goldman chronicles the making of this album, from its conception in Jamaica to the raucous but intense all-night studio sessions in London.

But The Book of Exodus is so much more than a making-of-a-record story. This remarkable book takes us through the history of Jamaican music, Marley’s own personal journey from the Trench Town ghetto to his status as global superstar, as well as Marley’s deep spiritual practice of Rastafari and the roots of this religion. Goldman also traces the biblical themes of the Exodus story, and its practical relevance to us today, through various other art forms, leading up to and culminating with Exodus.

Never before has there been such an intimate, first-hand portrait of Marley’s spirituality, his political involvement, and his life in exile in London, leading up to histriumphant return to the stage in Jamaica at the Peace Concert of 1978.

Here is an unforgettable portrait of Bob Marley and an acutely perceptive appreciation of his musical and spiritual legacy.

Preț: 107.34 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 161

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.54€ • 21.32$ • 17.17£

20.54€ • 21.32$ • 17.17£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 februarie-10 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400052868

ISBN-10: 1400052866

Pagini: 325

Ilustrații: 13 B&W PHOTOGRAPHS

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 1400052866

Pagini: 325

Ilustrații: 13 B&W PHOTOGRAPHS

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

Vivien Goldman is a writer, broadcaster, and musician who has devoted much of her work to Afro-Caribbean and global music. She is the adjunct professor of punk and reggae at NYU’s Clive Davis Department of Recorded Music. Originally from London, Goldman now resides in New York City. This is her fifth book.

Extras

Chapter 1

SEND US ANOTHER BROTHER MOSES

“I was a stranger in a strange land,” said Bob Marley to me softly. He quoted the biblical verse of Exodus 2:22 almost to himself, intimately, as if the verse had been a familiar friend during his London exile following the attempted assassination on his life that had happened three years before, just yards away.

The brand-new blond wood studio we were sitting in for this interview for a 1979 cover story for the oldest British rock weekly, Melody Maker, indicated that Marley was at a height of his career, artistically and professionally. Personally, too—we could hear children shouting excitedly as they played outside his house at 56 Hope Road, Kingston. He was about to record Survival, the first album he would ever make in his own studio, and it had taken him more than three decades to get there. He had truly survived a dangerous passage, and now, looking back, it was Exodus’s well-worn words that made sense of his experiences.

A chapter a day is the Rasta way, and Bob never went anywhere without his old King James Bible. Personalized with photos of Haile Selassie, it would lie open beside him, a ribbon marking the place, as he played his guitar by candlelight in whichever city he found himself. He had a way of isolating himself with the book, withdrawing from the other laughing musicians on the tour bus to ponder a particular passage, then challenging his bred’ren to debate it as vigorously as if they were playing soccer. Hurled into this unexpected journey, Exodus spoke to him now more than ever. Experiencing his own exile, accompanied by his old cohorts the Barrett brothers and Seeco, the grizzled Dread elder of the tribe, the ancestral narrative held a new meaning for Bob.

At the time it was recorded, Chris Blackwell recalls, it wasn’t even a given that “Exodus” would actually be the album’s title track. Only a very precise prophet could have determined that, a quarter century on, Bob and the Wailers’ anthems would be hailed by Time magazine as the Album of the Century; but Bob knew its significance. In the coming years, the themes that summoned Bob—such as repatriation to a place where you really belong—would become increasingly relevant to us all as the global population grew more dislocated and deracinated, and as refugees in ever increasing numbers would surge around the world, often looking to the Americas and Europe in their restless search for a home. Fleeing for a better life, or simply a life, they all rise to the challenge Bob chants in “Exodus”: “Are you satisfied with the life you’re living?”

Exodus was a natural theme for Marley. Its issues of power, betrayal, hope, disillusionments, and the search for serenity were all uppermost in his mind as he created the Exodus album with the Wailers. The Book of Exodus deals with leaving familiar oppression behind, braving the unknown, and letting faith guide you to a brighter future. These ideas have increasing relevance as we are hit by a contemporary litany of troubles that can be read like the plagues at a Seder, the communal Passover meal at which, every spring for the last two thousand years, the escape from Egypt has been reenacted, sometimes at great peril, wherever there are Jews. As each plague is named, you delicately dip a finger in your glass of wine and let a drop drip down for each disaster inflicted on the Egyptians. It’s understood that the red wine symbolizes a drop of blood. Today’s plagues, to which the ideas of Exodus very much apply, might read thus: wars; starvation; pestilences such as AIDS, malaria, and TB; genocide; ethnic cleansing; ecological collapse; greed; corruption; and disasters both natural and unnatural.

My intention in writing this book is to show the significance of Exodus both in Marley and the Wailers’ musical canon and in the man’s life. The light of the eternal themes of the Bible’s Book of Exodus shines in the Wailers’ work of that name, just as artists have reflected it throughout history. This work aims to show how the biblical narrative of the Hebrews’ flight from Pharaoh, orchestrated by Moses in conjunction with God, interlinks with Marley’s liberating message and the Rastas’ dream of the African diaspora’s return to the Motherland, inspired by their deity Haile Selassie.

Like the souls the Kabbalists describe as sparks of light, many artistic and cultural endeavors revolve around Exodus. By telling some of their stories, I hope to ignite those sparks into a steady flame that illuminates the universal meaning of both Exodus and the life and work of Bob Marley.

The narrative of the Hebrew Exodus from Egypt that comforted and strengthened Marley in his time of affliction is so graphic that it lends itself easily to a visual treatment. See the frames flash past: The organized slaughter of Hebrew male babies in the mean slave quarters, at Pharaoh’s command. The Israelite baby bobbing in the basket on the river, hidden by reeds, watched from a distance by his concerned sister, Miriam. She leaves only when she’s seen him discovered by Pharaoh’s daughter. Once adopted, Moses the Hebrew foundling is thrust into a classic role-reversal situation—the slave turned ruler. Then comes the political awakening, when Moses sees an Israelite slave abused by an Egyptian, and slays the oppressor. Struggling to hide the heavy corpse out of town in the sand, and having to deal with the knowledge that he too can kill. Moses’ rural retreat as a shepherd in Midion, and his first marriage, to Zipporah, the daughter of Jethro, who would become his mentor. The trippy encounter with a blazing bush that speaks for Hashem—it’s all like something at a Burning Man festival. Afterward, anyone can see his intimate exposure to glory, burned right on his face; Moses never looks the same after being so close to the celestial fire. To hamper social ease further, Moses stammers and is hard to understand. He relies on his brother, Aaron, as his lieutenant.

Still, Moses has unbeatable access to God, and carries the whole road map to freedom in his head. An effective leader, he wheels, deals, and hustles his tribe out of four hundred years of familiar captivity, in the same quest for the Promised Land that Bob Marley sings about in Exodus, except that Bob calls his destination Africa, the land of his father, Jah Rastafari. Moses’ tools include the plagues, which intensify from creepiness to cataclysm and whose grotesqueries, including insect swarms and infanticide, are still the stuff of horror flicks. There are the great Exodus set pieces that Cecil B. DeMille’s Cinemascope movie The Ten Commandments visualized so vividly in 1956: the Red Sea rearing into froth-topped liquid cliffs, and the tables turning when the freed captives see their old slave drivers drown.

With Moses leading the great trek, there is much dissension in the ranks, as the Hebrews dissed their deity, Hashem, with raves around the golden calf, exactly the sort of pagan idolatry that the patriarch, Abraham’s One God, had warned them about. With classic timing, the tribe unleashed their debauch while Moses was descending the mountain carrying the tablets with the Ten Commandments, the template for most of the world’s belief systems. Making matters worse, Aaron had apparently colluded in their defection from the new idea of the One God. It was when Moses, mad as only he could be, confronted the wrongdoers and smashed the sacred stone tablets before them that the transgressors finally felt the sting of their betrayal. Perhaps a defining moment in the history of guilt, it was only then that the ragtag Hebrews became the Jewish people.

Then, Moses’ final frustration, the last time God shows Moses his place. At his final face-to-face meeting with his Creator, Moses learns that he will not be allowed entry into Canaan, the Promised Land. He will have to find satisfaction in a glimpse from a mountaintop and the bittersweet realization that though he has hauled his tribe of fractious Hebrews out of slavery, Moses still won’t get to taste that milk and honey he’s been craving through forty years of false starts and wandering in the wilderness.

And the movement has never stopped. For refugees from Cambodia, Rwanda, Bosnia, all the world’s dispossessed populations shifting and scuffling restlessly round alien territories in search of shelter, the Bible’s Exodus suggests a possibility of finally finding a safe dwelling. In the trajectory of Moses’ tale—the man who makes it all happen, but ultimately only gets to glimpse the home he’d dreamed of—we learn that even being part of the survival process can be a privilege, its own reward. For those in rage, turmoil, or despair, Exodus and its echoes in the Psalms offer a sense of a solution, or at least the encouragement of inspiration.

Moses’ drastic reinvention as a reluctant, ambivalent leader demonstrates and represents all human potential for resurrection, change, and spiritual growth. The lessons Moses learned and delivered as the Ten Commandments serve as a fundamental moral yardstick for the dominant religious expressions that are collectively called Mosaic—Christianity, Islam, and Judaism.

The transformation implicit in the Exodus saga is reflected in our frontiers and cities. Both pleasure and conflict come from these new meshings and confrontations. Cultures collide and repel, or commingle and integrate, and new tribes take shape. Fresh strata of society shift, sift, and settle down as restlessly as grinding tectonic plates. Just when everything seems calm on the surface, communities seething with newness can suddenly convulse in a volcanic jolt of shock. That’s when bombs blow and blood flows. But after the pain and rage, always, is the hope for a smoother tomorrow. It is a magnet, the hope embodied in Exodus’s saga of a wandering tribe persistently following their faith to arrive at a place where they can live freely. And if you only get to glimpse the Promised Land from afar, isn’t there some achievement in just having got that far, and having helped to bring about that change?

There is an exhilarating promise of emerging into a new and better life on the other side, but even the bravest can feel frightened at leaping off the sharp edge of their bad reality into the dense cloud of the unknown. Yet none of the potential downsides of leaving the life you know can ultimately deter children of Exodus. Not the threat of living outside the law as refugee or illegal immigrant, the loneliness and longing for family and the familiar, or the strong possibility of confronting new obstacles.

The word exodus is now routinely used to describe any mass departure, whether it’s stars from a Hollywood agency, Israelis pulling out of Gaza, or New Orleans residents begging for a bus out of the Superdome to get somewhere, anywhere, away from the horror. Then, now, and always, Exodus suggests grueling trek for survival.

Some follow the idea of Exodus but never even get to see their Promised Land from afar. Roasted in a truck left in the sun at a border, drowned as a homemade raft sinks, or shot just yards away from freedom, every fallen refugee who dies chasing freedom is an Exodus martyr.

Yet within every belief system that identifies with Exodus, including Jews, Christians, Muslims, and Rastas, the dominant narrative of Exodus has a profound subplot: that great forty-year trek through the wilderness can also be a journey within oneself.

The drama of Exodus has a special meaning and offers a seductive sense of wish fulfillment for Bob Marley, and indeed any socially conscious artist’s primary constituency: the sufferers, the second-class citizens, denied a passport, whose movements or potential development are restricted; or anyone locked in a life-or-death struggle with a dictator, or just with a discouraging system.

By plugging into the ancestral sacred escape depicted in the Bible’s Book of Exodus, Marley was well aware of participating in a pre-Christian tradition: using Exodus’s dynamic saga of Moses leading the Israelite slaves’ escape from Egypt as a shorthand, or template, for rebel music. Marley’s Exodus has provoked reflection and an artistic response from all manner of artistic and political folk as well as religious people, and is a common thread linking seemingly very different lives. Enslaved Africans on the plantations of the American South turned to the story of Exodus and called on Moses to lead them in spirituals such as “Let My People Go.” Modern-day refugees and rebels in the front-line states of southern Africa (especially Zimbabwe), in Nicaragua and Poland, in Palestine and Israel all turned to Marley to articulate their existence. When Marley himself turned to Exodus for the same reason, the world embraced him as never before.

All these Exodus avatars were tuning in to the same fundamental frequency—the inspirational idea of Moses and his ragtag crew of recently freed Israelites. In his song “Exodus,” Bob Marley related that ancestral movement to the travels and travels of his own tribe, Jah People. They actually make it out of slavery and start life anew, in freedom, self-determined in their own place, led by Moses under the direction of their one deity. Also known as “Hashem,” “He who was, is, and will be,” and “the One whose name must not be uttered,” the One God is exultantly hailed by Rastafarians as Jah!

Having been privileged to share Bob Marley and the Wailers’ Exodus cycle in Kingston, London, and Europe, I originally wanted simply to tell the record’s story in this book. But as I researched, I found that the social, political, cultural, and spiritual implications of the album went much further than could be conveyed in a conventional musical story. The Wailers’ popularity had spread steadily beyond their original West Indian and student constituency since the band began in the early 1960s. But the vision, passion, and clarity of Exodus, and the band’s adept absorption of new textures, rhythms, and technologies into their reggae, turned Exodus into a truly important artistic statement and a pivotal release that consolidated Bob Marley and the Wailers’ career.

In an astonishing discussion with the Wailers’ bass player, Family Man Barrett, he explained to me how specifically he and Bob had chosen to build a new link in a conceptual chain of creation as old as the Bible when they recorded their Rasta anthem, “Exodus.” Discovering the connections between the members of the tribe of Exodus, from whatever century or country, and seeing their progress somehow refracted in Bob’s and the Wailers’ own experiences showed how often relationships and situations that seem specific and very much of their time are actually eternal.

Ironically, the immense publicity surrounding Bob’s narrow escape from death, and the sensational media scrutiny over his romance with the Miss World of the time, Cindy Breakspeare, catapulted Marley from the entertainment pages to the front-page headlines in virtually every international publication. So in trying to silence the Tuff Gong, his enemies just turned up his volume.

SEND US ANOTHER BROTHER MOSES

“I was a stranger in a strange land,” said Bob Marley to me softly. He quoted the biblical verse of Exodus 2:22 almost to himself, intimately, as if the verse had been a familiar friend during his London exile following the attempted assassination on his life that had happened three years before, just yards away.

The brand-new blond wood studio we were sitting in for this interview for a 1979 cover story for the oldest British rock weekly, Melody Maker, indicated that Marley was at a height of his career, artistically and professionally. Personally, too—we could hear children shouting excitedly as they played outside his house at 56 Hope Road, Kingston. He was about to record Survival, the first album he would ever make in his own studio, and it had taken him more than three decades to get there. He had truly survived a dangerous passage, and now, looking back, it was Exodus’s well-worn words that made sense of his experiences.

A chapter a day is the Rasta way, and Bob never went anywhere without his old King James Bible. Personalized with photos of Haile Selassie, it would lie open beside him, a ribbon marking the place, as he played his guitar by candlelight in whichever city he found himself. He had a way of isolating himself with the book, withdrawing from the other laughing musicians on the tour bus to ponder a particular passage, then challenging his bred’ren to debate it as vigorously as if they were playing soccer. Hurled into this unexpected journey, Exodus spoke to him now more than ever. Experiencing his own exile, accompanied by his old cohorts the Barrett brothers and Seeco, the grizzled Dread elder of the tribe, the ancestral narrative held a new meaning for Bob.

At the time it was recorded, Chris Blackwell recalls, it wasn’t even a given that “Exodus” would actually be the album’s title track. Only a very precise prophet could have determined that, a quarter century on, Bob and the Wailers’ anthems would be hailed by Time magazine as the Album of the Century; but Bob knew its significance. In the coming years, the themes that summoned Bob—such as repatriation to a place where you really belong—would become increasingly relevant to us all as the global population grew more dislocated and deracinated, and as refugees in ever increasing numbers would surge around the world, often looking to the Americas and Europe in their restless search for a home. Fleeing for a better life, or simply a life, they all rise to the challenge Bob chants in “Exodus”: “Are you satisfied with the life you’re living?”

Exodus was a natural theme for Marley. Its issues of power, betrayal, hope, disillusionments, and the search for serenity were all uppermost in his mind as he created the Exodus album with the Wailers. The Book of Exodus deals with leaving familiar oppression behind, braving the unknown, and letting faith guide you to a brighter future. These ideas have increasing relevance as we are hit by a contemporary litany of troubles that can be read like the plagues at a Seder, the communal Passover meal at which, every spring for the last two thousand years, the escape from Egypt has been reenacted, sometimes at great peril, wherever there are Jews. As each plague is named, you delicately dip a finger in your glass of wine and let a drop drip down for each disaster inflicted on the Egyptians. It’s understood that the red wine symbolizes a drop of blood. Today’s plagues, to which the ideas of Exodus very much apply, might read thus: wars; starvation; pestilences such as AIDS, malaria, and TB; genocide; ethnic cleansing; ecological collapse; greed; corruption; and disasters both natural and unnatural.

My intention in writing this book is to show the significance of Exodus both in Marley and the Wailers’ musical canon and in the man’s life. The light of the eternal themes of the Bible’s Book of Exodus shines in the Wailers’ work of that name, just as artists have reflected it throughout history. This work aims to show how the biblical narrative of the Hebrews’ flight from Pharaoh, orchestrated by Moses in conjunction with God, interlinks with Marley’s liberating message and the Rastas’ dream of the African diaspora’s return to the Motherland, inspired by their deity Haile Selassie.

Like the souls the Kabbalists describe as sparks of light, many artistic and cultural endeavors revolve around Exodus. By telling some of their stories, I hope to ignite those sparks into a steady flame that illuminates the universal meaning of both Exodus and the life and work of Bob Marley.

The narrative of the Hebrew Exodus from Egypt that comforted and strengthened Marley in his time of affliction is so graphic that it lends itself easily to a visual treatment. See the frames flash past: The organized slaughter of Hebrew male babies in the mean slave quarters, at Pharaoh’s command. The Israelite baby bobbing in the basket on the river, hidden by reeds, watched from a distance by his concerned sister, Miriam. She leaves only when she’s seen him discovered by Pharaoh’s daughter. Once adopted, Moses the Hebrew foundling is thrust into a classic role-reversal situation—the slave turned ruler. Then comes the political awakening, when Moses sees an Israelite slave abused by an Egyptian, and slays the oppressor. Struggling to hide the heavy corpse out of town in the sand, and having to deal with the knowledge that he too can kill. Moses’ rural retreat as a shepherd in Midion, and his first marriage, to Zipporah, the daughter of Jethro, who would become his mentor. The trippy encounter with a blazing bush that speaks for Hashem—it’s all like something at a Burning Man festival. Afterward, anyone can see his intimate exposure to glory, burned right on his face; Moses never looks the same after being so close to the celestial fire. To hamper social ease further, Moses stammers and is hard to understand. He relies on his brother, Aaron, as his lieutenant.

Still, Moses has unbeatable access to God, and carries the whole road map to freedom in his head. An effective leader, he wheels, deals, and hustles his tribe out of four hundred years of familiar captivity, in the same quest for the Promised Land that Bob Marley sings about in Exodus, except that Bob calls his destination Africa, the land of his father, Jah Rastafari. Moses’ tools include the plagues, which intensify from creepiness to cataclysm and whose grotesqueries, including insect swarms and infanticide, are still the stuff of horror flicks. There are the great Exodus set pieces that Cecil B. DeMille’s Cinemascope movie The Ten Commandments visualized so vividly in 1956: the Red Sea rearing into froth-topped liquid cliffs, and the tables turning when the freed captives see their old slave drivers drown.

With Moses leading the great trek, there is much dissension in the ranks, as the Hebrews dissed their deity, Hashem, with raves around the golden calf, exactly the sort of pagan idolatry that the patriarch, Abraham’s One God, had warned them about. With classic timing, the tribe unleashed their debauch while Moses was descending the mountain carrying the tablets with the Ten Commandments, the template for most of the world’s belief systems. Making matters worse, Aaron had apparently colluded in their defection from the new idea of the One God. It was when Moses, mad as only he could be, confronted the wrongdoers and smashed the sacred stone tablets before them that the transgressors finally felt the sting of their betrayal. Perhaps a defining moment in the history of guilt, it was only then that the ragtag Hebrews became the Jewish people.

Then, Moses’ final frustration, the last time God shows Moses his place. At his final face-to-face meeting with his Creator, Moses learns that he will not be allowed entry into Canaan, the Promised Land. He will have to find satisfaction in a glimpse from a mountaintop and the bittersweet realization that though he has hauled his tribe of fractious Hebrews out of slavery, Moses still won’t get to taste that milk and honey he’s been craving through forty years of false starts and wandering in the wilderness.

And the movement has never stopped. For refugees from Cambodia, Rwanda, Bosnia, all the world’s dispossessed populations shifting and scuffling restlessly round alien territories in search of shelter, the Bible’s Exodus suggests a possibility of finally finding a safe dwelling. In the trajectory of Moses’ tale—the man who makes it all happen, but ultimately only gets to glimpse the home he’d dreamed of—we learn that even being part of the survival process can be a privilege, its own reward. For those in rage, turmoil, or despair, Exodus and its echoes in the Psalms offer a sense of a solution, or at least the encouragement of inspiration.

Moses’ drastic reinvention as a reluctant, ambivalent leader demonstrates and represents all human potential for resurrection, change, and spiritual growth. The lessons Moses learned and delivered as the Ten Commandments serve as a fundamental moral yardstick for the dominant religious expressions that are collectively called Mosaic—Christianity, Islam, and Judaism.

The transformation implicit in the Exodus saga is reflected in our frontiers and cities. Both pleasure and conflict come from these new meshings and confrontations. Cultures collide and repel, or commingle and integrate, and new tribes take shape. Fresh strata of society shift, sift, and settle down as restlessly as grinding tectonic plates. Just when everything seems calm on the surface, communities seething with newness can suddenly convulse in a volcanic jolt of shock. That’s when bombs blow and blood flows. But after the pain and rage, always, is the hope for a smoother tomorrow. It is a magnet, the hope embodied in Exodus’s saga of a wandering tribe persistently following their faith to arrive at a place where they can live freely. And if you only get to glimpse the Promised Land from afar, isn’t there some achievement in just having got that far, and having helped to bring about that change?

There is an exhilarating promise of emerging into a new and better life on the other side, but even the bravest can feel frightened at leaping off the sharp edge of their bad reality into the dense cloud of the unknown. Yet none of the potential downsides of leaving the life you know can ultimately deter children of Exodus. Not the threat of living outside the law as refugee or illegal immigrant, the loneliness and longing for family and the familiar, or the strong possibility of confronting new obstacles.

The word exodus is now routinely used to describe any mass departure, whether it’s stars from a Hollywood agency, Israelis pulling out of Gaza, or New Orleans residents begging for a bus out of the Superdome to get somewhere, anywhere, away from the horror. Then, now, and always, Exodus suggests grueling trek for survival.

Some follow the idea of Exodus but never even get to see their Promised Land from afar. Roasted in a truck left in the sun at a border, drowned as a homemade raft sinks, or shot just yards away from freedom, every fallen refugee who dies chasing freedom is an Exodus martyr.

Yet within every belief system that identifies with Exodus, including Jews, Christians, Muslims, and Rastas, the dominant narrative of Exodus has a profound subplot: that great forty-year trek through the wilderness can also be a journey within oneself.

The drama of Exodus has a special meaning and offers a seductive sense of wish fulfillment for Bob Marley, and indeed any socially conscious artist’s primary constituency: the sufferers, the second-class citizens, denied a passport, whose movements or potential development are restricted; or anyone locked in a life-or-death struggle with a dictator, or just with a discouraging system.

By plugging into the ancestral sacred escape depicted in the Bible’s Book of Exodus, Marley was well aware of participating in a pre-Christian tradition: using Exodus’s dynamic saga of Moses leading the Israelite slaves’ escape from Egypt as a shorthand, or template, for rebel music. Marley’s Exodus has provoked reflection and an artistic response from all manner of artistic and political folk as well as religious people, and is a common thread linking seemingly very different lives. Enslaved Africans on the plantations of the American South turned to the story of Exodus and called on Moses to lead them in spirituals such as “Let My People Go.” Modern-day refugees and rebels in the front-line states of southern Africa (especially Zimbabwe), in Nicaragua and Poland, in Palestine and Israel all turned to Marley to articulate their existence. When Marley himself turned to Exodus for the same reason, the world embraced him as never before.

All these Exodus avatars were tuning in to the same fundamental frequency—the inspirational idea of Moses and his ragtag crew of recently freed Israelites. In his song “Exodus,” Bob Marley related that ancestral movement to the travels and travels of his own tribe, Jah People. They actually make it out of slavery and start life anew, in freedom, self-determined in their own place, led by Moses under the direction of their one deity. Also known as “Hashem,” “He who was, is, and will be,” and “the One whose name must not be uttered,” the One God is exultantly hailed by Rastafarians as Jah!

Having been privileged to share Bob Marley and the Wailers’ Exodus cycle in Kingston, London, and Europe, I originally wanted simply to tell the record’s story in this book. But as I researched, I found that the social, political, cultural, and spiritual implications of the album went much further than could be conveyed in a conventional musical story. The Wailers’ popularity had spread steadily beyond their original West Indian and student constituency since the band began in the early 1960s. But the vision, passion, and clarity of Exodus, and the band’s adept absorption of new textures, rhythms, and technologies into their reggae, turned Exodus into a truly important artistic statement and a pivotal release that consolidated Bob Marley and the Wailers’ career.

In an astonishing discussion with the Wailers’ bass player, Family Man Barrett, he explained to me how specifically he and Bob had chosen to build a new link in a conceptual chain of creation as old as the Bible when they recorded their Rasta anthem, “Exodus.” Discovering the connections between the members of the tribe of Exodus, from whatever century or country, and seeing their progress somehow refracted in Bob’s and the Wailers’ own experiences showed how often relationships and situations that seem specific and very much of their time are actually eternal.

Ironically, the immense publicity surrounding Bob’s narrow escape from death, and the sensational media scrutiny over his romance with the Miss World of the time, Cindy Breakspeare, catapulted Marley from the entertainment pages to the front-page headlines in virtually every international publication. So in trying to silence the Tuff Gong, his enemies just turned up his volume.

Recenzii

“Vivien Goldman is a soldier who understood where we were coming from with our music and spread the message with her writing. She is on the Zion Train.” —Aston “Family Man” Barrett, cofounder and bass player of the Wailers

“Finely reported, vividly written, and politically astute, Vivien Goldman travels with Bob Marley on the intimate journey that led him to become the voice of the Exodus. A fundamental human conflict, Exodus expresses the eternal quest for land, identity, and in Marley’s case, a quest for harmony.” —Mariane Pearl, author of A Mighty Heart: The Brave Life and Death of My Husband, Danny Pearl

“Finely reported, vividly written, and politically astute, Vivien Goldman travels with Bob Marley on the intimate journey that led him to become the voice of the Exodus. A fundamental human conflict, Exodus expresses the eternal quest for land, identity, and in Marley’s case, a quest for harmony.” —Mariane Pearl, author of A Mighty Heart: The Brave Life and Death of My Husband, Danny Pearl

Descriere

The journalist who helped introduce Bob Marley to the West chronicles the making of his masterpiece, Exodus, named "Album of the Century" by "Time" magazine. 20 photos.