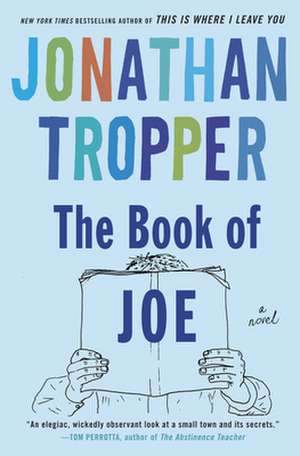

The Book of Joe

Autor Jonathan Tropperen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2005

Fans of Nick Hornby and Jennifer Weiner will love this book, by turns howling funny, fiercely intelligent, and achingly poignant. As evidenced by The Book of Joe's success in both the foreign and movie markets, Jonathan Tropper has created a compelling, incredibly resonant story.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 97.76 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 147

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.71€ • 19.46$ • 15.45£

18.71€ • 19.46$ • 15.45£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385338103

ISBN-10: 0385338104

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 143 x 208 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Ediția:Trade Paperback.

Editura: Bantam

ISBN-10: 0385338104

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 143 x 208 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Ediția:Trade Paperback.

Editura: Bantam

Notă biografică

Jonathan Tropper is the author of Everything Changes, The Book of Joe, which was a BookSense selection, and Plan B. He lives with his wife, Elizabeth, and their children in Westchester, New York, where he teaches writing at Manhattanville College. How to Talk to a Widower was optioned by Paramount Pictures, and Everything Changes and The Book of Joe are also in development as feature films.

Extras

Chapter One

Just a few scant months after my mother's suicide, I walked into the garage, looking for my baseball glove, and discovered Cindy Posner on her knees, animatedly performing fellatio on my older brother, Brad. He was leaned up against our father's tool rack, the hammers and wrenches jingling musically on their hooks like Christmas bells as he rocked gently back and forth, staring up at the ceiling with a curiously bored expression. His jeans and boxers were bunched up around his knees, his hand resting absently on her bobbing head as she went about her surprisingly noisy oral ministrations. I stood there transfixed until Brad, sensing my arrival, looked down from the ceiling and our eyes met. There was no alarm in his eyes, no embarrassment at having been caught in so compromising a position, but only the same look of tired resignation he always seemed to have where I was concerned. That's right. I'm getting a blow job in the garage. It's a safe bet you never will. Cindy, whose back was to me,

noticed me a few seconds later and became instantly hysterical, cursing and shrieking at me as I beat a hasty, if somewhat belated retreat. I was thirteen years old at the time.

It's entirely possible that Cindy would have handled herself with a bit more aplomb had she known that seventeen years later the incident would be immortalized in the first chapter of the best-selling autobiographical novel that I would write and, as with most successful books, in the inevitable movie that would follow shortly thereafter. By then she was no longer Cindy Posner, but Cindy Goffman, having married Brad in their senior year of college, and I think it's fair to say that this inclusion in my book did nothing to improve our already tenuous relationship. The book is titled Bush Falls, after the small Connecticut town where I grew up, a term I use loosely, since the jury's still out on whether I've actually ever grown up at all.

By now you've certainly heard of Bush Falls, or no doubt seen the movie, which starred Leonardo DiCaprio and Kirsten Dunst, and did some pretty decent box office. Or maybe you read about the major controversy it caused back in my hometown, where they even went so far as to put together a class action libel suit against me that never went anywhere. Either way, the book was a runaway best-seller about two and a half years ago, and for a little while there, I became a minor celebrity.

Any schmuck can be unhappy when things aren't going well, but it takes a truly unique variety of schmuck, a real innovator in the schmuck field, to be unhappy when things are going as great as they are for me. At thirty-four, I'm rich, successful, have sex on a fairly regular basis, and live in a three-bedroom luxury apartment on Manhattan's Upper West Side. This should be ample reason to feel that I have the world by its proverbial short hairs, yet I've recently developed the sneaking suspicion that underneath it all I am one sad, lonely son of a bitch, and have been for some time.

While there is no paucity of women in my life these days, it nevertheless seems that every relationship I've had in the two and a half years since the publication of Bush Falls has lasted almost exactly eight weeks, following the same essential flight pattern. In the first week I pull out all the stops—fancy restaurants, concerts, Broadway shows, and trendy nightclubs—modestly avoiding any high-minded banter concerning the literary world in favor of current events, movies, and celebrity gossip, which are of course the real currency in the New York dating scene, even if no one will admit it. Not that being a celebrated author isn't worth something, but stories about Miramax parties or how you hung out on the set with Leo and Kirsten will get you laid much faster and by a better caliber of woman. Weeks two and three are generally the best, the time you'd like to bottle and store, primarily due to the endorphin rush of fresh sex. At some point in the fourth week, I fall in love, briefly considering the possibility that this could be The One, and then everything pretty much goes to shit in slow motion. I waffle, I vacillate, I get insecure, I come on too strong. I conduct little psychological experiments on myself or the woman involved. You get the picture. This goes on for a couple of painfully awkward weeks, and then we both spend week seven in the fervent hope that the relationship will magically dissolve on its own, through an act of god or spontaneous combustion—anything to avoid having to actually navigate the tediously perilous terrain of a full-blown breakup. The last week is spent "taking some time," which ends with a final, perfunctory phone call finalizing the arrangement and resolving any outstanding logistics. I'll drop the bag and Donna Karan sweater you left in my apartment with the doorman, you can keep the books I lent you, thanks for the memories, no hard feelings, let's stay friends, et cetera, ad nauseam.

I know it bespeaks poor character to blame others for your problems, but I'm fairly certain this is all Carly's fault. Carly Diamond was my high school girlfriend, the first—and, to date, only—woman I've ever loved. We were together for our entire senior year, and loved each other with the fierce, timeless conviction of teenagers. That was the same year that all the terrible events described in my novel occurred, and my relationship with her was the lone bright spot in my dismally expanding universe.

If you want to get technical about it, we never actually broke up. We graduated high school and went to different colleges, Carly up to Harvard and me down to NYU. We tried to do the long-distance thing, but my adamant refusal to return to the Falls for our mutual vacations made it difficult, and over time we simply grew apart, but we never formally dissolved our relationship. After college, Carly came to New York to study journalism, at which point we embarked on one of those long, messy postgraduate friendships where you have just enough sex to thoroughly confuse the hell out of each other and ultimately, through a sequence of poor timing and third-party complications, fuck the life out of what was once the purest thing you'd ever known.

We still loved each other then, that much was obvious, but while Carly seemed ready to reclaim our relationship, I kept finding reasons to remain uncommitted. No matter how much I loved her—and I did—I was constantly comparing the timbre of our relationship with the raw beauty, the sense of discovery, that had attended our every moment when we were seventeen. By the time I finally understood the colossal nature of my mistake, it was too late and Carly was gone. Losing her once was sad but understandable. Carelessly discarding the second chance afforded me by the fates required such a potent mixture of arrogance and stupidity that it had to have been cultivated, because I'm fairly certain I wasn't always such a complete asshole.

I've never forgiven myself for the head games I played with her during her years in New York, wooing her whenever I felt her slipping away and then pulling back the minute I felt secure again. I allowed her unwavering belief in us to sustain me even at times when I didn't share it, leading her along with promises, both spoken and implied but never fulfilled. By the time I finally began to understand how badly I'd been using her, I had used her up completely. She left New York heartbroken and disgusted, returning to the Falls to accept a position as managing editor of The Minuteman, the town's local paper. Every time I think I've gotten over her, I find myself waking in the middle of the night, pining for her with such desperation that you would think it was only yesterday and not ten years ago that she left.

Since then not a day goes by that I am not haunted by a vague but powerful sense of regret, every woman I date serving as a reminder of what I allowed myself to lose. So in a way, it's because of Carly that I'm alone in bed in the middle of the night when the phone rings, its electronic wail piercing the insulated silence of my apartment like a siren. Generally speaking, when people call you at two in the morning, it won't be good news. My first thought, as I swim up through the dense wormwood haze of alcohol-induced sleep, is that it has to be Natalie, my borderline psychotic ex-girlfriend, calling to scream at me. I don't know what damage I could have possibly done to her apparently fragile psyche in eight weeks, but her latest therapist has convinced her that she still has significant unresolved issues with me and that it behooves her, from a mental wellness perspective, to call me, day or night, whenever it occurs to her to remind me what an insensitive jerk I was. The calls started about four months ago and now come fairly regularly, both at home and on my cell phone, thirty-second installments of furious invective with abundant smatterings of vulgarity, requiring absolutely no participation from me. If it happens that I'm unavailable, Nat is perfectly content to leave her colorful harangues on my voice mail. She's always been drawn to radical therapy, much as lately I seem to be drawn to women who require it.

The phone keeps ringing. I don't know if it's been two rings or ten; I just know it isn't stopping. I roll onto my side and rub my face vigorously, trying to coax the sleep from my head. The skin of my cheeks feels like putty, loose and fleshy, as if the night's prior excesses have dramatically aged me. I went out with Owen earlier, and, as usual, we got supremely shit-faced. Owen Hobbs, agent extraordinaire, is my emissary not only to the literary establishment but to all conceivable manner of chaos and debauchery. I never drink except when I'm with him, and then I drink like him, voraciously and with great ceremony. He's made me rich, and he gets fifteen percent, which has turned out to be a better foundation for a friendship than you might think, usually worth the thrashing hangover that always follows what he terms our "celebrations." A night with Owen inevitably takes the shape of a downward spiral upon which in retrospect I can identify only a handful of the spins and turns as I nurse my wounded body back into the realm where consciousness and sobriety rudely intersect. And while I'm still loosely ensconced in that precariously optimistic place where drunkenness has departed and the hangover is still mulling over its options, I nevertheless feel nauseous and off-kilter.

The phone. Without moving my head from where it lies embedded in my pillow, I reach out in the general direction of my night table, knocking over some magazines, an open bottle of Aleve, and a half-filled mug of water, which splashes mutely on the plush ecru carpeting. The cordless is actually on the floor to begin with, and when I finally locate it and hoist it up to my immobile head, cold droplets of spilled water seep into my ear canal like slugs.

"Hello?" It's a woman's voice. "Joe?"

"Who's this," I say, lifting my head slightly so as to move the mouthpiece somewhere in the general vicinity of my mouth. It's not Nat, which means some speaking on my part might be required.

"It's Cindy."

"Cindy," I repeat carefully.

"Your sister-in-law."

"Oh." That Cindy.

"Your father's had a stroke." My brother's wife blurts this out like a premature punch line. In most families, such monumental news would merit a thoughtfully orchestrated presentation carefully constructed to minimize shock while facilitating gradual acceptance. Such grave news would probably warrant a personal delivery from the blood relative, in this case my older brother, Brad. But I am family to Brad and my father only in a strictly legal sense. On those rare occasions when they do acknowledge my existence, it's out of some vague sense of civic responsibility, like paying taxes or jury duty.

"Where's Brad?" I say, keeping my voice just above a whisper as people who live alone do needlessly at night.

"He's over at the hospital," Cindy says dully. She's never liked me, but that isn't entirely her fault. I've never actually given her any reason to.

"What happened?"

"Your father's in a coma," she says matter-of-factly, as if I've asked her the time. "It's quite serious. They don't know if he's going to make it."

"Don't sugarcoat it, now," I mutter, sitting up in my bed, which causes pockets of violence to erupt among the trillions of neurons rallying like soccer fans in my left temple.

There follows a pause. "What?" Cindy says. I remind myself that my particular style of irony is usually lost on her. I take a quick emotional inventory, searching for any reaction to the news that my father might be dying: grief, shock, anger, denial. Something.

"Nothing," I say.

Another uncomfortable pause. "Well, Brad said you shouldn't come tonight but that you should meet him at the hospital tomorrow."

"Tomorrow," I repeat dumbly, looking at the clock again. It already is tomorrow.

"You can stay with us, or you can stay at your father's place. Actually, his house is closer to the hospital."

"Okay." Somewhere in my diminishing stupor, it registers that my presence is being requested or, rather, presumed. Either way, it's highly unusual.

"Well, which is it? Do you want to stay with us or at your dad's?"

A more compassionate person might wait for the shock to wear off before pressing ahead with the petty logistics of the whole thing, but Cindy has little in the way of compassion where I'm concerned.

"Whatever," I say. "Whatever's better for you guys."

"Well, it's usually a madhouse here, with the kids and all," she says. "I think you'll be happier in your old house."

"Okay."

"Your father's in Mercy Hospital. Do you need directions?" Her question is quite possibly a deliberate dig at the fact that I haven't been back to the Falls in almost seventeen years.

"Have they moved it?"

"No."

"Then I should be fine."

I can hear her shallow breathing as another uncomfortable silence grows like a tumor over the phone line. Cindy, three years older than me, was the archetypal popular girl in Bush Falls High School. With lustrous dark hair and an exquisite body sculpted to perfection in her cheerleading drills, she was unquestionably the most universally employed muse of the wet dream among the teenaged boys in Bush Falls at that time. I myself made often and effective use of her in my fantasies, fueled in no small part by what I saw in the garage that day. But now she's thirty-seven and a mother of three, and even over the phone, you can hear the varicose veins in her voice.

Just a few scant months after my mother's suicide, I walked into the garage, looking for my baseball glove, and discovered Cindy Posner on her knees, animatedly performing fellatio on my older brother, Brad. He was leaned up against our father's tool rack, the hammers and wrenches jingling musically on their hooks like Christmas bells as he rocked gently back and forth, staring up at the ceiling with a curiously bored expression. His jeans and boxers were bunched up around his knees, his hand resting absently on her bobbing head as she went about her surprisingly noisy oral ministrations. I stood there transfixed until Brad, sensing my arrival, looked down from the ceiling and our eyes met. There was no alarm in his eyes, no embarrassment at having been caught in so compromising a position, but only the same look of tired resignation he always seemed to have where I was concerned. That's right. I'm getting a blow job in the garage. It's a safe bet you never will. Cindy, whose back was to me,

noticed me a few seconds later and became instantly hysterical, cursing and shrieking at me as I beat a hasty, if somewhat belated retreat. I was thirteen years old at the time.

It's entirely possible that Cindy would have handled herself with a bit more aplomb had she known that seventeen years later the incident would be immortalized in the first chapter of the best-selling autobiographical novel that I would write and, as with most successful books, in the inevitable movie that would follow shortly thereafter. By then she was no longer Cindy Posner, but Cindy Goffman, having married Brad in their senior year of college, and I think it's fair to say that this inclusion in my book did nothing to improve our already tenuous relationship. The book is titled Bush Falls, after the small Connecticut town where I grew up, a term I use loosely, since the jury's still out on whether I've actually ever grown up at all.

By now you've certainly heard of Bush Falls, or no doubt seen the movie, which starred Leonardo DiCaprio and Kirsten Dunst, and did some pretty decent box office. Or maybe you read about the major controversy it caused back in my hometown, where they even went so far as to put together a class action libel suit against me that never went anywhere. Either way, the book was a runaway best-seller about two and a half years ago, and for a little while there, I became a minor celebrity.

Any schmuck can be unhappy when things aren't going well, but it takes a truly unique variety of schmuck, a real innovator in the schmuck field, to be unhappy when things are going as great as they are for me. At thirty-four, I'm rich, successful, have sex on a fairly regular basis, and live in a three-bedroom luxury apartment on Manhattan's Upper West Side. This should be ample reason to feel that I have the world by its proverbial short hairs, yet I've recently developed the sneaking suspicion that underneath it all I am one sad, lonely son of a bitch, and have been for some time.

While there is no paucity of women in my life these days, it nevertheless seems that every relationship I've had in the two and a half years since the publication of Bush Falls has lasted almost exactly eight weeks, following the same essential flight pattern. In the first week I pull out all the stops—fancy restaurants, concerts, Broadway shows, and trendy nightclubs—modestly avoiding any high-minded banter concerning the literary world in favor of current events, movies, and celebrity gossip, which are of course the real currency in the New York dating scene, even if no one will admit it. Not that being a celebrated author isn't worth something, but stories about Miramax parties or how you hung out on the set with Leo and Kirsten will get you laid much faster and by a better caliber of woman. Weeks two and three are generally the best, the time you'd like to bottle and store, primarily due to the endorphin rush of fresh sex. At some point in the fourth week, I fall in love, briefly considering the possibility that this could be The One, and then everything pretty much goes to shit in slow motion. I waffle, I vacillate, I get insecure, I come on too strong. I conduct little psychological experiments on myself or the woman involved. You get the picture. This goes on for a couple of painfully awkward weeks, and then we both spend week seven in the fervent hope that the relationship will magically dissolve on its own, through an act of god or spontaneous combustion—anything to avoid having to actually navigate the tediously perilous terrain of a full-blown breakup. The last week is spent "taking some time," which ends with a final, perfunctory phone call finalizing the arrangement and resolving any outstanding logistics. I'll drop the bag and Donna Karan sweater you left in my apartment with the doorman, you can keep the books I lent you, thanks for the memories, no hard feelings, let's stay friends, et cetera, ad nauseam.

I know it bespeaks poor character to blame others for your problems, but I'm fairly certain this is all Carly's fault. Carly Diamond was my high school girlfriend, the first—and, to date, only—woman I've ever loved. We were together for our entire senior year, and loved each other with the fierce, timeless conviction of teenagers. That was the same year that all the terrible events described in my novel occurred, and my relationship with her was the lone bright spot in my dismally expanding universe.

If you want to get technical about it, we never actually broke up. We graduated high school and went to different colleges, Carly up to Harvard and me down to NYU. We tried to do the long-distance thing, but my adamant refusal to return to the Falls for our mutual vacations made it difficult, and over time we simply grew apart, but we never formally dissolved our relationship. After college, Carly came to New York to study journalism, at which point we embarked on one of those long, messy postgraduate friendships where you have just enough sex to thoroughly confuse the hell out of each other and ultimately, through a sequence of poor timing and third-party complications, fuck the life out of what was once the purest thing you'd ever known.

We still loved each other then, that much was obvious, but while Carly seemed ready to reclaim our relationship, I kept finding reasons to remain uncommitted. No matter how much I loved her—and I did—I was constantly comparing the timbre of our relationship with the raw beauty, the sense of discovery, that had attended our every moment when we were seventeen. By the time I finally understood the colossal nature of my mistake, it was too late and Carly was gone. Losing her once was sad but understandable. Carelessly discarding the second chance afforded me by the fates required such a potent mixture of arrogance and stupidity that it had to have been cultivated, because I'm fairly certain I wasn't always such a complete asshole.

I've never forgiven myself for the head games I played with her during her years in New York, wooing her whenever I felt her slipping away and then pulling back the minute I felt secure again. I allowed her unwavering belief in us to sustain me even at times when I didn't share it, leading her along with promises, both spoken and implied but never fulfilled. By the time I finally began to understand how badly I'd been using her, I had used her up completely. She left New York heartbroken and disgusted, returning to the Falls to accept a position as managing editor of The Minuteman, the town's local paper. Every time I think I've gotten over her, I find myself waking in the middle of the night, pining for her with such desperation that you would think it was only yesterday and not ten years ago that she left.

Since then not a day goes by that I am not haunted by a vague but powerful sense of regret, every woman I date serving as a reminder of what I allowed myself to lose. So in a way, it's because of Carly that I'm alone in bed in the middle of the night when the phone rings, its electronic wail piercing the insulated silence of my apartment like a siren. Generally speaking, when people call you at two in the morning, it won't be good news. My first thought, as I swim up through the dense wormwood haze of alcohol-induced sleep, is that it has to be Natalie, my borderline psychotic ex-girlfriend, calling to scream at me. I don't know what damage I could have possibly done to her apparently fragile psyche in eight weeks, but her latest therapist has convinced her that she still has significant unresolved issues with me and that it behooves her, from a mental wellness perspective, to call me, day or night, whenever it occurs to her to remind me what an insensitive jerk I was. The calls started about four months ago and now come fairly regularly, both at home and on my cell phone, thirty-second installments of furious invective with abundant smatterings of vulgarity, requiring absolutely no participation from me. If it happens that I'm unavailable, Nat is perfectly content to leave her colorful harangues on my voice mail. She's always been drawn to radical therapy, much as lately I seem to be drawn to women who require it.

The phone keeps ringing. I don't know if it's been two rings or ten; I just know it isn't stopping. I roll onto my side and rub my face vigorously, trying to coax the sleep from my head. The skin of my cheeks feels like putty, loose and fleshy, as if the night's prior excesses have dramatically aged me. I went out with Owen earlier, and, as usual, we got supremely shit-faced. Owen Hobbs, agent extraordinaire, is my emissary not only to the literary establishment but to all conceivable manner of chaos and debauchery. I never drink except when I'm with him, and then I drink like him, voraciously and with great ceremony. He's made me rich, and he gets fifteen percent, which has turned out to be a better foundation for a friendship than you might think, usually worth the thrashing hangover that always follows what he terms our "celebrations." A night with Owen inevitably takes the shape of a downward spiral upon which in retrospect I can identify only a handful of the spins and turns as I nurse my wounded body back into the realm where consciousness and sobriety rudely intersect. And while I'm still loosely ensconced in that precariously optimistic place where drunkenness has departed and the hangover is still mulling over its options, I nevertheless feel nauseous and off-kilter.

The phone. Without moving my head from where it lies embedded in my pillow, I reach out in the general direction of my night table, knocking over some magazines, an open bottle of Aleve, and a half-filled mug of water, which splashes mutely on the plush ecru carpeting. The cordless is actually on the floor to begin with, and when I finally locate it and hoist it up to my immobile head, cold droplets of spilled water seep into my ear canal like slugs.

"Hello?" It's a woman's voice. "Joe?"

"Who's this," I say, lifting my head slightly so as to move the mouthpiece somewhere in the general vicinity of my mouth. It's not Nat, which means some speaking on my part might be required.

"It's Cindy."

"Cindy," I repeat carefully.

"Your sister-in-law."

"Oh." That Cindy.

"Your father's had a stroke." My brother's wife blurts this out like a premature punch line. In most families, such monumental news would merit a thoughtfully orchestrated presentation carefully constructed to minimize shock while facilitating gradual acceptance. Such grave news would probably warrant a personal delivery from the blood relative, in this case my older brother, Brad. But I am family to Brad and my father only in a strictly legal sense. On those rare occasions when they do acknowledge my existence, it's out of some vague sense of civic responsibility, like paying taxes or jury duty.

"Where's Brad?" I say, keeping my voice just above a whisper as people who live alone do needlessly at night.

"He's over at the hospital," Cindy says dully. She's never liked me, but that isn't entirely her fault. I've never actually given her any reason to.

"What happened?"

"Your father's in a coma," she says matter-of-factly, as if I've asked her the time. "It's quite serious. They don't know if he's going to make it."

"Don't sugarcoat it, now," I mutter, sitting up in my bed, which causes pockets of violence to erupt among the trillions of neurons rallying like soccer fans in my left temple.

There follows a pause. "What?" Cindy says. I remind myself that my particular style of irony is usually lost on her. I take a quick emotional inventory, searching for any reaction to the news that my father might be dying: grief, shock, anger, denial. Something.

"Nothing," I say.

Another uncomfortable pause. "Well, Brad said you shouldn't come tonight but that you should meet him at the hospital tomorrow."

"Tomorrow," I repeat dumbly, looking at the clock again. It already is tomorrow.

"You can stay with us, or you can stay at your father's place. Actually, his house is closer to the hospital."

"Okay." Somewhere in my diminishing stupor, it registers that my presence is being requested or, rather, presumed. Either way, it's highly unusual.

"Well, which is it? Do you want to stay with us or at your dad's?"

A more compassionate person might wait for the shock to wear off before pressing ahead with the petty logistics of the whole thing, but Cindy has little in the way of compassion where I'm concerned.

"Whatever," I say. "Whatever's better for you guys."

"Well, it's usually a madhouse here, with the kids and all," she says. "I think you'll be happier in your old house."

"Okay."

"Your father's in Mercy Hospital. Do you need directions?" Her question is quite possibly a deliberate dig at the fact that I haven't been back to the Falls in almost seventeen years.

"Have they moved it?"

"No."

"Then I should be fine."

I can hear her shallow breathing as another uncomfortable silence grows like a tumor over the phone line. Cindy, three years older than me, was the archetypal popular girl in Bush Falls High School. With lustrous dark hair and an exquisite body sculpted to perfection in her cheerleading drills, she was unquestionably the most universally employed muse of the wet dream among the teenaged boys in Bush Falls at that time. I myself made often and effective use of her in my fantasies, fueled in no small part by what I saw in the garage that day. But now she's thirty-seven and a mother of three, and even over the phone, you can hear the varicose veins in her voice.

Recenzii

"A beautifully crafted book of enormous heart, humility, wit, honesty, and vulnerability. You want to call your friends at 3:00 AM and read whole passages out loud. You want to press it into the hands of strangers. You cannot stop thinking about it because it has rearranged your very molecules. You know that kind of book? This is that kind of book. The Book of Joe is utterly magnificent. I wish I'd written it myself."—Augusten Burroughs, author of Running with Scissors

"The Book of Joe is an elegiac, wickedly observant look at a small town and its secrets. In Jonathan Tropper's highly readable novel, the problem isn't that you can't go home again, it's that eventually you have to, whether you like it or not."—Tom Perrotta, author of Election and Joe College

"A sweet, deft and sentimental coming-of-age-at-34 story. .... [Tropper's] humor keeps his tale buoyant."—Daily News (NY)

"The Book of Joe will make you laugh and cry. Tropper has a very readable style, and Joe is a character you can connect with, warts and all."—Associated Press

"The Book of Joe is an elegiac, wickedly observant look at a small town and its secrets. In Jonathan Tropper's highly readable novel, the problem isn't that you can't go home again, it's that eventually you have to, whether you like it or not."—Tom Perrotta, author of Election and Joe College

"A sweet, deft and sentimental coming-of-age-at-34 story. .... [Tropper's] humor keeps his tale buoyant."—Daily News (NY)

"The Book of Joe will make you laugh and cry. Tropper has a very readable style, and Joe is a character you can connect with, warts and all."—Associated Press

Descriere

Wickedly funny, piercingly intelligent, and achingly poignant, "The Book Of Joe" illuminates the intricacies of family, friendship, and lost love. Film rights have been optioned by Brad Pitt and Jennifer Aniston's production company.