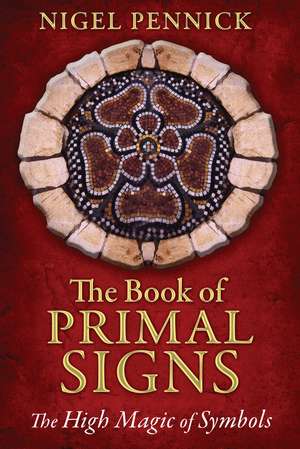

The Book of Primal Signs: The High Magic of Symbols

Autor Nigel Pennicken Limba Engleză Paperback – 4 aug 2014

Preț: 62.15 lei

Preț vechi: 82.24 lei

-24% Nou

Puncte Express: 93

Preț estimativ în valută:

11.89€ • 12.34$ • 9.94£

11.89€ • 12.34$ • 9.94£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 februarie-12 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781620553152

ISBN-10: 1620553155

Pagini: 240

Ilustrații: 340 b&w illustrations

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Ediția:2nd Edition, New Edition

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Destiny Books

ISBN-10: 1620553155

Pagini: 240

Ilustrații: 340 b&w illustrations

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Ediția:2nd Edition, New Edition

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Destiny Books

Notă biografică

Nigel Pennick, trained as a biologist, has traveled and lectured extensively in Europe and the United States on sacred geometry, the spirit of place, spiritual arts and crafts, and labyrinths. He is the author and illustrator of more than 50 books, including The Pagan Book of Days, as well as numerous pamphlets, scientific papers, and articles. A musician with the Traditional Music of Cambridgeshire Collective, he lives in Cambridge, England.

Extras

15. THE SWASTIKA

The swastika, svastika, or sauvastika, otherwise known as fylfot, fyrfos, gammadion, or tetraskelion, and in heraldry as the cross potent rebated, is an often misunderstood glyph because of its use by the German National Socialists between 1919 and 1945. However, it is by no means to be defined solely by one of its many historical uses any more than any other glyph is. Historical opinions and uses are all part of a glyph’s history but do not define it once and for all as having a certain fixed meaning. For centuries, Catholic priests officiated at the Mass wearing vestments covered with swastikas. But now no Christian priest wears the glyph.

Similarly, it appeared on the memorial shields of English knights, including Sir John Daubernon (1277) and Sir Thomas de Hop (ca. 1370). From the nineteenth century onward, the swastika became of great interest to researchers into esoteric matters. Opinions on the meaning of the glyph are many. There are numerous writings by occult, esoteric, political, and religious authors about the swastika, and the subject is by no means exhausted (e.g., Pennick 1979; Taylor 2006).

In northern Europe, the swastika has been long associated with the god of thunder. In 1888 Llewellyn Jewitt commented:

In northern mythology the Fylfot is known as the Hammer of Thorr, the Scandinavian god, or Thunderer, and is called “Thorr’s Hammer” or the “Thunderbolt.” The emblem of this god, Thorr or the Thunderer, was . . . a thunderbolt or a hammer of gold, which hammer was frequently represented by a Fylfot. (Jewitt 1888)

Guido List in 1910 classified the fyrfos as his second Ur-Glyphe (primal glyph). He saw it as a fire sign, one of the most holy signs of Armanendom. Edred Thorsson categorizes the swastika among the “quadraplectic signs” that signify the sky, the sun, and lightning and notes that the swastika is called sólarhvél (sun wheel) and Thórshammarr in Old Norse.

The swastika was used as a house mark of bell founders in England, mainly in the shires of Derby, Lincoln, Nottingham, Stafford, and York. The foundry owned by the Heathcote family in Chesterfield used the sign for at least four generations in the sixteenth century (Taylor 2006, 77-80, 163). There are medieval inscriptions on bells that invoke warding power against storms. “As the ringing of the church bells in times of tempest was superstitiously believed to drive away thunder, probably the old Thunderer superstition that had not died out of the popular mind might have had something to do with it being the sign of Thorr, who was believed to have power over storms and tempests, and of himself throwing the thunderbolts” (Jewitt 1888).

Smiths have used the pattern in protective ironwork of window grilles and gateways, perhaps to serve the same function against the flash. A sixteenth-century window grille at Colmar in Alsace is shown below, and on the following page is a wrought-iron gate at Richmond in Surrey, England.

In his book The Occult Causes of the Present War, in which he portrayed both German culture in general and Naziism in particular as satanically inspired, Lewis Spence stated that the swastika “is not only a most ancient pagan device, but is well known as a satanist symbol--‘the broken cross’--typifying, as it does, the Christian cross defaced . . . it is unquestionably to be found in numerous grimoires and magical books of the more demonic kind” (Spence 1941, 108). The myth that the swastika was reversed by Adolf Hitler to make it an evil sign also appears to have originated in World War II propaganda, perhaps attributable to H. G. Wells.

In the nineteenth century, before Madame Blavatsky popularized it, the swastika had been used for about one thousand seven hundred years as a Christian sign. The Round Church in Cambridge was completely rebuilt in 1841, and a leaded glass window dating from that time still has its Christian swastikas. It was designed by the heraldic artist Thomas Willement (Taylor 2006, 58-59). Three swastikas were in the backward form and one in the forward. When the window was damaged in the 1980s, the forward image was replaced by a backward one, probably because of the Nazi use of the forward form.

The swastika is a Finnish national sign, and aircraft of the Finnish air force long carried the emblem. Finland’s state honor, the Suomen Valkoisen Ruusun ritarikunta (Order of the White Rose), was instituted in 1919 by Baron Carl Gustav Mannerheim. When designed in 1919, the Collar of the Order worn by a Commander Grand Cross was composed of white roses alternating with equal-armed swastikas. The swastikas were replaced in 1963 by eightfold sigils representing spruce branches (Hieronymussen & Strüwing 1967, 49, 129-31). The Finnish swastika is acknowledged in the logo of the Turun Kala Oy fish canning company.

In 1969 I was a participant in an alternative press syndicate, The Cambridge Native Press. This group of autonomous magazines circled around the “underground newspaper” Cambridge Voice. Among the publications issued under the CNP aegis was the poetry and literary magazine Swastika, for which I did artwork. The first issue appeared in March 1969. In the first editorial the editor Christopher Crutchley wrote:

Welcome to the first edition of Swastika, the new Cambridge poetry and literary magazine. First let it be said that this mag is not Nazi propaganda as the title might suggest to those who can only remember the last war. Cast your mind back further than that, and some of you will already know that the swastika has been used as a religious symbol connected with fertility for 10,000 years. This symbol must be re-instated in society--but with its original meaning.

The swastika, svastika, or sauvastika, otherwise known as fylfot, fyrfos, gammadion, or tetraskelion, and in heraldry as the cross potent rebated, is an often misunderstood glyph because of its use by the German National Socialists between 1919 and 1945. However, it is by no means to be defined solely by one of its many historical uses any more than any other glyph is. Historical opinions and uses are all part of a glyph’s history but do not define it once and for all as having a certain fixed meaning. For centuries, Catholic priests officiated at the Mass wearing vestments covered with swastikas. But now no Christian priest wears the glyph.

Similarly, it appeared on the memorial shields of English knights, including Sir John Daubernon (1277) and Sir Thomas de Hop (ca. 1370). From the nineteenth century onward, the swastika became of great interest to researchers into esoteric matters. Opinions on the meaning of the glyph are many. There are numerous writings by occult, esoteric, political, and religious authors about the swastika, and the subject is by no means exhausted (e.g., Pennick 1979; Taylor 2006).

In northern Europe, the swastika has been long associated with the god of thunder. In 1888 Llewellyn Jewitt commented:

In northern mythology the Fylfot is known as the Hammer of Thorr, the Scandinavian god, or Thunderer, and is called “Thorr’s Hammer” or the “Thunderbolt.” The emblem of this god, Thorr or the Thunderer, was . . . a thunderbolt or a hammer of gold, which hammer was frequently represented by a Fylfot. (Jewitt 1888)

Guido List in 1910 classified the fyrfos as his second Ur-Glyphe (primal glyph). He saw it as a fire sign, one of the most holy signs of Armanendom. Edred Thorsson categorizes the swastika among the “quadraplectic signs” that signify the sky, the sun, and lightning and notes that the swastika is called sólarhvél (sun wheel) and Thórshammarr in Old Norse.

The swastika was used as a house mark of bell founders in England, mainly in the shires of Derby, Lincoln, Nottingham, Stafford, and York. The foundry owned by the Heathcote family in Chesterfield used the sign for at least four generations in the sixteenth century (Taylor 2006, 77-80, 163). There are medieval inscriptions on bells that invoke warding power against storms. “As the ringing of the church bells in times of tempest was superstitiously believed to drive away thunder, probably the old Thunderer superstition that had not died out of the popular mind might have had something to do with it being the sign of Thorr, who was believed to have power over storms and tempests, and of himself throwing the thunderbolts” (Jewitt 1888).

Smiths have used the pattern in protective ironwork of window grilles and gateways, perhaps to serve the same function against the flash. A sixteenth-century window grille at Colmar in Alsace is shown below, and on the following page is a wrought-iron gate at Richmond in Surrey, England.

In his book The Occult Causes of the Present War, in which he portrayed both German culture in general and Naziism in particular as satanically inspired, Lewis Spence stated that the swastika “is not only a most ancient pagan device, but is well known as a satanist symbol--‘the broken cross’--typifying, as it does, the Christian cross defaced . . . it is unquestionably to be found in numerous grimoires and magical books of the more demonic kind” (Spence 1941, 108). The myth that the swastika was reversed by Adolf Hitler to make it an evil sign also appears to have originated in World War II propaganda, perhaps attributable to H. G. Wells.

In the nineteenth century, before Madame Blavatsky popularized it, the swastika had been used for about one thousand seven hundred years as a Christian sign. The Round Church in Cambridge was completely rebuilt in 1841, and a leaded glass window dating from that time still has its Christian swastikas. It was designed by the heraldic artist Thomas Willement (Taylor 2006, 58-59). Three swastikas were in the backward form and one in the forward. When the window was damaged in the 1980s, the forward image was replaced by a backward one, probably because of the Nazi use of the forward form.

The swastika is a Finnish national sign, and aircraft of the Finnish air force long carried the emblem. Finland’s state honor, the Suomen Valkoisen Ruusun ritarikunta (Order of the White Rose), was instituted in 1919 by Baron Carl Gustav Mannerheim. When designed in 1919, the Collar of the Order worn by a Commander Grand Cross was composed of white roses alternating with equal-armed swastikas. The swastikas were replaced in 1963 by eightfold sigils representing spruce branches (Hieronymussen & Strüwing 1967, 49, 129-31). The Finnish swastika is acknowledged in the logo of the Turun Kala Oy fish canning company.

In 1969 I was a participant in an alternative press syndicate, The Cambridge Native Press. This group of autonomous magazines circled around the “underground newspaper” Cambridge Voice. Among the publications issued under the CNP aegis was the poetry and literary magazine Swastika, for which I did artwork. The first issue appeared in March 1969. In the first editorial the editor Christopher Crutchley wrote:

Welcome to the first edition of Swastika, the new Cambridge poetry and literary magazine. First let it be said that this mag is not Nazi propaganda as the title might suggest to those who can only remember the last war. Cast your mind back further than that, and some of you will already know that the swastika has been used as a religious symbol connected with fertility for 10,000 years. This symbol must be re-instated in society--but with its original meaning.

Cuprins

Preface: Primal Signs, Traditional Glyphs, and Symbols

Introduction: A Symbolic World

Part I

Traditional Glyphs, Signs, Sigils, and Symbols in Practice

The Runes

Runic Logos and Defunct Organizations

The Pitfalls of Symbology

New Names, New Meanings

The Public Use of Glyphs

Part II

A Box of Glyphs

1 The Sun, the Circle, and the Sun Wheel

2 The Akhet and the Twin Towers

3 The Eight-Spoked Wheel

4 Crosses

5 The Crescent Moon, Star, and Comet

6 Solar Light and Lightning

7 The Cosmic or Philosophical Egg

8 The Omphalos

9 The Pineapple

10 The Tree of Life

11 The Fleur-de-Lys

12 The Rose

13 The Heart

14 Human and Eldritch Heads

15 The Swastika

16 The Skirl, Yin and Yang

17 The Pothook

18 The Trefot

19 The Horseshoe

20 Tools and Craft Symbols

21 The X, Gyfu, Daeg, and Ing Glyphs

22 The Hexflower

23 Woven Patterns

24 Plaits and Knots

25 Straw Plaits

26 The Pentagram

27 The Hexagram

28 The Checker

29 House Marks, Craftsmen’s Marks, and Sigils

30 Miscellaneous Magical Glyphs

31 Alternative and New Spiritual Glyphs

32 Local Glyphs

33 Symbolic Beasts

34 The Serpent

35 The Phoenix

36 The Cockerel and Weathercocks

37 The Eye and the Peacock

38 The Sigils of Mammon

39 The Death’s Head

Bibliography

Index

Introduction: A Symbolic World

Part I

Traditional Glyphs, Signs, Sigils, and Symbols in Practice

The Runes

Runic Logos and Defunct Organizations

The Pitfalls of Symbology

New Names, New Meanings

The Public Use of Glyphs

Part II

A Box of Glyphs

1 The Sun, the Circle, and the Sun Wheel

2 The Akhet and the Twin Towers

3 The Eight-Spoked Wheel

4 Crosses

5 The Crescent Moon, Star, and Comet

6 Solar Light and Lightning

7 The Cosmic or Philosophical Egg

8 The Omphalos

9 The Pineapple

10 The Tree of Life

11 The Fleur-de-Lys

12 The Rose

13 The Heart

14 Human and Eldritch Heads

15 The Swastika

16 The Skirl, Yin and Yang

17 The Pothook

18 The Trefot

19 The Horseshoe

20 Tools and Craft Symbols

21 The X, Gyfu, Daeg, and Ing Glyphs

22 The Hexflower

23 Woven Patterns

24 Plaits and Knots

25 Straw Plaits

26 The Pentagram

27 The Hexagram

28 The Checker

29 House Marks, Craftsmen’s Marks, and Sigils

30 Miscellaneous Magical Glyphs

31 Alternative and New Spiritual Glyphs

32 Local Glyphs

33 Symbolic Beasts

34 The Serpent

35 The Phoenix

36 The Cockerel and Weathercocks

37 The Eye and the Peacock

38 The Sigils of Mammon

39 The Death’s Head

Bibliography

Index

Recenzii

“Symbols are like signposts directing us into the realm of the subconscious and the spiritual; they are flashpoints that stir emotions and trigger deeper--even divine--connections. But they also take on lives of their own, twining across times and cultures, and Nigel Pennick has always had his finger on their pulse. The Book of Primal Signs is a veritable thesaurus of traditional symbolism, spanning from prehistory to today. This is a vital guidebook to a hidden world that is, most thankfully and wondrously, still in plain view.”

“Solidly referenced and carefully illustrated, The Book of Primal Signs seems to travel everywhere and touch everything . . .”

“This book is highly recommended to researchers and students of the occult as an immensely valuable survey of symbols from an author with sophisticated spiritual insights and an invaluable multi-disciplinary approach to his subject. Kudos!”

“Solidly referenced and carefully illustrated, The Book of Primal Signs seems to travel everywhere and touch everything . . .”

“This book is highly recommended to researchers and students of the occult as an immensely valuable survey of symbols from an author with sophisticated spiritual insights and an invaluable multi-disciplinary approach to his subject. Kudos!”

Descriere

An in-depth study of the sacred meanings behind ancient and enduring symbols.