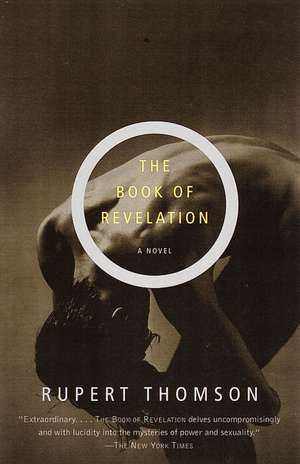

The Book of Revelation: Rupert Thomson

Autor Rupert Thomsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2000

Stepping out of his Amsterdam studio one April afternoon to buy cigarettes for his girlfriend, a dashing 29-year old Englishman reflects on their wonderful seven-year relationship, and his stellar career as an internationally acclaimed dancer and choreographer. But the nameless protagonist's destiny takes an unthinkably horrifying turn when a trio of mysterious cloaked and hooded women kidnap him, chain him to the floor of a stark white room to keep as their sexual prisoner, and subjected him to eighteen days of humiliation, mutilation, and rape. Then, after a bizarrely public performance, he is released, only to be held captive in the purgatory of his own guilt and torment: The realization that no one will believe his strange story. Coolly revelatory, meticulously crafted, The Book of Revelation is Rupert Thomson at his imaginative best.

Preț: 105.82 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 159

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.25€ • 21.99$ • 17.01£

20.25€ • 21.99$ • 17.01£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 02-16 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375708459

ISBN-10: 0375708456

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0375708456

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Rupert Thomson is the author of five previous novels -- of which Soft!, The Insult, Air & Fire, and The Five Gates of Hell are available in Vintage paperback. He lives in London.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

One

I can see it all so clearly, even now. The studio canteen was empty, and I was sitting in the corner, by the window. Sunlight angled across the table, dividing the smooth, blond wood into two equal halves, one bright, one dark; I remember thinking that it looked heraldic, like a shield. An ashtray stood in front of me, the sun's rays shattering against its chunky glass. Beside it, someone's coffee cup, still half full but long since cold. It was an ordinary moment in an ordinary day -- a break between rehearsals. . . .

I had just opened my notebook and was about to put pen to paper when I heard footsteps to my right, a dancer's footsteps, light but purposeful. I looked up to see Brigitte, my girlfriend, walking towards me in her dark-green leotard and her laddered tights, her hair tied back with a piece of mauve velvet. She was frowning. She had run out of cigarettes, she told me, and there were none in the machine. Would I go out and buy her some more?

I stared at her. "I thought I bought you a packet yesterday."

"I finished them," she said.

"You've smoked twenty cigarettes since yesterday?"

Brigitte just looked at me.

"You'll get cancer," I told her.

"I don't care," she said.

This was an argument we had had before, of course, and I soon relented. In the end, I was pleased to be doing something for her. It's a quality I often see in myself when I look back, that eagerness to please. I had wanted to make her happy from the first moment I saw her. I would always remember the morning when she walked into the studio, fresh from the Jeune Ballet de France, and how she stood by the piano, pinning up her crunchy, chestnut-coloured hair, and I would always remember making love to her a few days later, and the expression on her face as she knelt above me, a curious mixture of arrogance and ecstasy, her eyes so dark that I could not tell the difference between the pupils and the irises. . . .

Brigitte had moved to the window. She stood there, staring out, one hand propped on her hip. Smiling, I reached for my sweater and pulled it over the old torn shirt I always wore for dance class.

"I won't be long," I said.

Outside, the weather was beautiful. Though May was still two weeks away, the sun felt warm against my back as I walked off down the street. I saw a man cycle over a bridge, singing loudly to himself, as people often do in Amsterdam, the tails of his pale linen jacket flapping. There was a look of anticipation on his face -- anticipation of summer, and the heat that was to come. . . .

I had been living with Brigitte for seven years. We rented the top two floors of a house on Egelantiersgracht, one of the prettier, less well-known canals. We had skylights, exotic plants, a tank of fish; we had a south-facing terrace where we would eat breakfast in the summer. Since we were both members of the same company, we saw each other twenty-four hours a day; in fact, in all the time that we had lived together, I don't suppose we had spent more than three or four nights apart. As dancers, we had had a good deal of success. We had performed all over the world -- in Osaka, in São Paulo, in Tel Aviv. The public loved us. So did the critics. I was also beginning to be acclaimed for my choreography (I had created three short ballets for the company, the most recent of which had won an international prize). At the age of twenty-nine, I had every reason to feel blessed. There was nothing about my life I would have changed, not if you had offered me riches beyond my wildest imaginings -- though, as I walked to the shop that afternoon, I do remember wishing that Brigitte would give up smoking. . . .

I followed my usual route. After crossing the bridge, I turned left along the street that bordered the canal. I walked a short distance, then I took a right turn, into the shadows of a narrow alley. The air down there smelled of damp plaster, stagnant water, and the brick walls of the houses were grouted with an ancient, lime-green moss. I passed the watchmaker's where a cat lay sleeping in the window, its front paws flexing luxuriously, its fur as grey as smoke or lead. I passed a shop that sold oriental vases and lamps with shades of coloured glass and bronze statues of half-naked girls. Like the man on the bicycle, I had music in my head: it was a composition by Juan Martin, which I was hoping to use in my next ballet. . . .

Halfway down the alley, at the point where it curved slightly to the left, I stopped and looked up. Just there, the buildings were five storeys high, and seemed to lean towards each other, all but shutting out the light.

The sky had shrunk to a thin ribbon of blue.

As I brought my eyes back down, I saw them, three figures dressed in hoods and cloaks, like part of a dream that had become detached, somehow, and floated free, into the day. The sight did not surprise me. In fact, I might even have laughed. I suppose I thought they were on their way to a fancy-dress party -- or else they were street-theatre people, perhaps. . . .

Whatever the truth was, they didn't seem particularly out of place in the alley. No, what surprised me, if anything, was the fact that they recognised me. They knew my name. They told me they had seen me dance. Yes, many times. I was wonderful, they said. One of the women clapped her hands together in delight at the coincidence. Another took me by the arm, the better to convey her enthusiasm.

While they were clustered round me, asking questions, I felt a sharp pain in the back of my right hand. Looking down, I caught a glimpse of a needle leaving one of my veins, a needle against the darkness of a cloak. I heard myself ask the women what they were doing -- What are you doing? -- only to drift away, fall backwards, while the black steeples of their hoods remained above me, and my words too, written on the sky, that narrow strip of blue, like a message trailed behind a plane. . . .

It is only five minutes' walk from the studio to the shop that sells newspapers and cigarettes. I ought to have been there and back in a quarter of an hour. But half an hour passed, then forty-five minutes, and still there was no sign of me.

I had last seen Brigitte standing at the canteen window, one hand propped on her hip. How long, I wonder, did she stay like that? And what went through her mind as she stood there, staring down into the street? Did she think our little argument had upset me? Did she think I was punishing her?

I imagine she must have turned away eventually, reaching up with both hands to re-tie the scrap of velvet that held her hair back from her face. Probably she would have muttered something to herself in French. Faít chier. Merde. She would still have been longing for that cigarette, of course. All her nerve-ends jangling.

Maybe, in the end, she asked Fernanda for a Marlboro Light and smoked it by the pay-phone in the corridor outside the studio.

I doubt she danced too well that afternoon.

That night, when I did not come home, Brigitte rang several of my friends. She rang my parents too, in England. No one knew anything. No one could help. Two days later, a leading Dutch newspaper published an article containing a brief history of my career and a small portrait photograph. It wasn't front-page news. After all, there was no real story as yet. I was a dancer and a choreographer, and I had gone missing. That was it. Various people at the company came up with various different theories -- a nervous breakdown of some kind, personal problems -- but none of them involved foul play. My parents offered a reward for any information that might throw light on my whereabouts. Nobody came forward.

All this I found out later.

There was a point at which Brigitte began to resent me for putting her in such a difficult position. She found it humiliating, not knowing where I was; I was making her look ridiculous. It must have been then that it occurred to her that I might have left her -- for another woman, presumably. How cowardly of me to say nothing. How cowardly, to just go. Brigitte was half French, half Portuguese, and her pride had always resembled a kind of anger. There was nothing constant or steady about it. No, it flared like a struck match. When she was interviewed by the police she told them that I had abandoned her, betrayed her. She couldn't produce any evidence to support her theory, nor could she point to any precedent (in our many years together I had never once been unfaithful to her), yet the police took her seriously. A woman's intuition, after all. What's more, she lived with me. She was supposed to know me best. So if that was what she thought. . . . The police did not send out any search parties for me. They did not scour the countryside with tracker dogs or drag the city's waterways. They did not even put up Missing Person posters. Why would they? I was just a man having an affair.

This, too, I found out later.

One other thing. The last person to see me before I disappeared was not Brigitte, but Stefan Elmers. Stefan was a freelance stills photographer who worked for the company. He took pictures of us dancing, black-and-white pictures that were used in programmes and publicity. Both Brigitte and I counted Stefan as a friend.

As I was walking along the canal that afternoon -- and this could only have been moments before I turned into the alley -- Stefan happened to drive past me in his car. Usually he would have stopped and talked to me, or else he would have shouted out of the window, something cheeky, knowing Stefan, but there was another car behind him, right behind him, so he just kept going.

Apparently, I looked happy.

For the next eighteen days no one had the slightest idea where I was.

I can see it all so clearly, even now. The studio canteen was empty, and I was sitting in the corner, by the window. Sunlight angled across the table, dividing the smooth, blond wood into two equal halves, one bright, one dark; I remember thinking that it looked heraldic, like a shield. An ashtray stood in front of me, the sun's rays shattering against its chunky glass. Beside it, someone's coffee cup, still half full but long since cold. It was an ordinary moment in an ordinary day -- a break between rehearsals. . . .

I had just opened my notebook and was about to put pen to paper when I heard footsteps to my right, a dancer's footsteps, light but purposeful. I looked up to see Brigitte, my girlfriend, walking towards me in her dark-green leotard and her laddered tights, her hair tied back with a piece of mauve velvet. She was frowning. She had run out of cigarettes, she told me, and there were none in the machine. Would I go out and buy her some more?

I stared at her. "I thought I bought you a packet yesterday."

"I finished them," she said.

"You've smoked twenty cigarettes since yesterday?"

Brigitte just looked at me.

"You'll get cancer," I told her.

"I don't care," she said.

This was an argument we had had before, of course, and I soon relented. In the end, I was pleased to be doing something for her. It's a quality I often see in myself when I look back, that eagerness to please. I had wanted to make her happy from the first moment I saw her. I would always remember the morning when she walked into the studio, fresh from the Jeune Ballet de France, and how she stood by the piano, pinning up her crunchy, chestnut-coloured hair, and I would always remember making love to her a few days later, and the expression on her face as she knelt above me, a curious mixture of arrogance and ecstasy, her eyes so dark that I could not tell the difference between the pupils and the irises. . . .

Brigitte had moved to the window. She stood there, staring out, one hand propped on her hip. Smiling, I reached for my sweater and pulled it over the old torn shirt I always wore for dance class.

"I won't be long," I said.

Outside, the weather was beautiful. Though May was still two weeks away, the sun felt warm against my back as I walked off down the street. I saw a man cycle over a bridge, singing loudly to himself, as people often do in Amsterdam, the tails of his pale linen jacket flapping. There was a look of anticipation on his face -- anticipation of summer, and the heat that was to come. . . .

I had been living with Brigitte for seven years. We rented the top two floors of a house on Egelantiersgracht, one of the prettier, less well-known canals. We had skylights, exotic plants, a tank of fish; we had a south-facing terrace where we would eat breakfast in the summer. Since we were both members of the same company, we saw each other twenty-four hours a day; in fact, in all the time that we had lived together, I don't suppose we had spent more than three or four nights apart. As dancers, we had had a good deal of success. We had performed all over the world -- in Osaka, in São Paulo, in Tel Aviv. The public loved us. So did the critics. I was also beginning to be acclaimed for my choreography (I had created three short ballets for the company, the most recent of which had won an international prize). At the age of twenty-nine, I had every reason to feel blessed. There was nothing about my life I would have changed, not if you had offered me riches beyond my wildest imaginings -- though, as I walked to the shop that afternoon, I do remember wishing that Brigitte would give up smoking. . . .

I followed my usual route. After crossing the bridge, I turned left along the street that bordered the canal. I walked a short distance, then I took a right turn, into the shadows of a narrow alley. The air down there smelled of damp plaster, stagnant water, and the brick walls of the houses were grouted with an ancient, lime-green moss. I passed the watchmaker's where a cat lay sleeping in the window, its front paws flexing luxuriously, its fur as grey as smoke or lead. I passed a shop that sold oriental vases and lamps with shades of coloured glass and bronze statues of half-naked girls. Like the man on the bicycle, I had music in my head: it was a composition by Juan Martin, which I was hoping to use in my next ballet. . . .

Halfway down the alley, at the point where it curved slightly to the left, I stopped and looked up. Just there, the buildings were five storeys high, and seemed to lean towards each other, all but shutting out the light.

The sky had shrunk to a thin ribbon of blue.

As I brought my eyes back down, I saw them, three figures dressed in hoods and cloaks, like part of a dream that had become detached, somehow, and floated free, into the day. The sight did not surprise me. In fact, I might even have laughed. I suppose I thought they were on their way to a fancy-dress party -- or else they were street-theatre people, perhaps. . . .

Whatever the truth was, they didn't seem particularly out of place in the alley. No, what surprised me, if anything, was the fact that they recognised me. They knew my name. They told me they had seen me dance. Yes, many times. I was wonderful, they said. One of the women clapped her hands together in delight at the coincidence. Another took me by the arm, the better to convey her enthusiasm.

While they were clustered round me, asking questions, I felt a sharp pain in the back of my right hand. Looking down, I caught a glimpse of a needle leaving one of my veins, a needle against the darkness of a cloak. I heard myself ask the women what they were doing -- What are you doing? -- only to drift away, fall backwards, while the black steeples of their hoods remained above me, and my words too, written on the sky, that narrow strip of blue, like a message trailed behind a plane. . . .

It is only five minutes' walk from the studio to the shop that sells newspapers and cigarettes. I ought to have been there and back in a quarter of an hour. But half an hour passed, then forty-five minutes, and still there was no sign of me.

I had last seen Brigitte standing at the canteen window, one hand propped on her hip. How long, I wonder, did she stay like that? And what went through her mind as she stood there, staring down into the street? Did she think our little argument had upset me? Did she think I was punishing her?

I imagine she must have turned away eventually, reaching up with both hands to re-tie the scrap of velvet that held her hair back from her face. Probably she would have muttered something to herself in French. Faít chier. Merde. She would still have been longing for that cigarette, of course. All her nerve-ends jangling.

Maybe, in the end, she asked Fernanda for a Marlboro Light and smoked it by the pay-phone in the corridor outside the studio.

I doubt she danced too well that afternoon.

That night, when I did not come home, Brigitte rang several of my friends. She rang my parents too, in England. No one knew anything. No one could help. Two days later, a leading Dutch newspaper published an article containing a brief history of my career and a small portrait photograph. It wasn't front-page news. After all, there was no real story as yet. I was a dancer and a choreographer, and I had gone missing. That was it. Various people at the company came up with various different theories -- a nervous breakdown of some kind, personal problems -- but none of them involved foul play. My parents offered a reward for any information that might throw light on my whereabouts. Nobody came forward.

All this I found out later.

There was a point at which Brigitte began to resent me for putting her in such a difficult position. She found it humiliating, not knowing where I was; I was making her look ridiculous. It must have been then that it occurred to her that I might have left her -- for another woman, presumably. How cowardly of me to say nothing. How cowardly, to just go. Brigitte was half French, half Portuguese, and her pride had always resembled a kind of anger. There was nothing constant or steady about it. No, it flared like a struck match. When she was interviewed by the police she told them that I had abandoned her, betrayed her. She couldn't produce any evidence to support her theory, nor could she point to any precedent (in our many years together I had never once been unfaithful to her), yet the police took her seriously. A woman's intuition, after all. What's more, she lived with me. She was supposed to know me best. So if that was what she thought. . . . The police did not send out any search parties for me. They did not scour the countryside with tracker dogs or drag the city's waterways. They did not even put up Missing Person posters. Why would they? I was just a man having an affair.

This, too, I found out later.

One other thing. The last person to see me before I disappeared was not Brigitte, but Stefan Elmers. Stefan was a freelance stills photographer who worked for the company. He took pictures of us dancing, black-and-white pictures that were used in programmes and publicity. Both Brigitte and I counted Stefan as a friend.

As I was walking along the canal that afternoon -- and this could only have been moments before I turned into the alley -- Stefan happened to drive past me in his car. Usually he would have stopped and talked to me, or else he would have shouted out of the window, something cheeky, knowing Stefan, but there was another car behind him, right behind him, so he just kept going.

Apparently, I looked happy.

For the next eighteen days no one had the slightest idea where I was.

Descriere

In this edgy, psychological thriller, Thomson fearlessly enters the darkest realm of the human spirit to reveal the sinister connection between sexuality and power. On a bright spring day in Amsterdam, a young man is accosted by three cloaked women who hold him as their sexual prisoner. Those 18 days, and the subsequent years of his life, make this a wildly compelling and deeply disturbing novel.