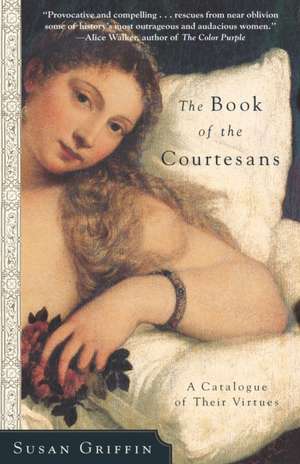

The Book of the Courtesans: A Catalogue of Their Virtues

Autor Susan Griffinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2002

From Veronica Franco, who graced the palazzos of sixteenth-century Venice, and Madame de Pompadour, the arbiter of all things fashionable at Versailles during the reign of Lous XV, to La Belle Otero of the grand boulevards of Paris in the Gay Nineties and Marion Davies, who took Hollywood by storm in the 1920's and 1930's, The Book of the Courtesans enticingly illustrates the intricacies of their lavish lifestyles and incredible life stories. Fascinating true tales and enlightening snippets from courtesans' memoirs further reveal how these cunning women seized their opportunity to become the West's first liberators, free to choose their own lovers and command remarkable respect.

Delving into his scintillating world, The Book of the Courtesans is an impeccably researched, beautifully crafted portrait of some of the most intriguing figures in women's history.

Preț: 101.99 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 153

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.52€ • 20.32$ • 16.50£

19.52€ • 20.32$ • 16.50£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15 februarie-01 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767904513

ISBN-10: 0767904516

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767904516

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

The author of more than twenty books, Susan Griffin has won dozens of awards for her work as a feminist, poet, writer, essayist, playwright, and filmmaker. Her book A Chorus of Stones was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award. The recipient of an Emmy, a MacArthur Grant, and a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, she is a frequent contributor to Ms. magazine, The New York Times Book Review, and numerous other publications. She lives in Berkeley, California.

Extras

Chapter One

Timing

Ripeness is all.

--William Shakespeare

It is always wise to begin with a mystery. Translucent, invisible, continually in motion, timing is difficult to discern and just as hard to describe. Nevertheless, the appeal of anyone who possesses this virtue is certainly palpable. Let us suppose, for example, that in the bare beginnings of the twentieth century, in say 1905, you chance to attend a party given at the country estate of Etienne Balsan. You may find yourself smiling at a woman who passes you on the stairs. And though you have not met her yet, you realize you are wishing that you will soon. Later, when you see her talking with a small group across the room, you are almost embarrassed at how often your eyes wander in her direction. What is it about her? She is good-looking but not extraordinarily so. No, it is something else that draws you. An air of indefinable excitement that seems to radiate out in waves around her.

You see that her presence affects those who are standing near her. The atmosphere in that part of the room is distinctly electric. The way she is dressed gives you a clue. She is wearing what looks like a man's riding jacket, only cut to follow the lines of her small body. Though the look is eccentric, the style seems to place her at the very edge of the present moment. And the look in her eyes, almost mocking, gives you the intriguing impression that she is seeing just past the precipice of what is happening now, that she is, in fact, fully aware of (and more than ready for) the moment which has not quite arrived yet. Still, she has not given herself to the future. Fully here, her movements and gestures are perfectly syncopated with the soundless rhythm to which you suddenly realize the whole room is moving. As the air fairly crackles around her, you begin to believe that she is helping to bring new possibilities into being, including the new worlds that seem to have emerged in your own imagination since the first moment you laid eyes on her. Only at the end of the day, do you learn that she is your host's lover, a young woman named Gabrielle. When, later, you hear her name spoken all over Paris, you are not so surprised. What was it about her that was so extraordinary? Her timing was brilliant.

Still, as compelling as a woman with good timing is, the question remains: Why should this virtue be placed first in our catalogue? Asked what could make a woman so attractive that a man would be willing to spend a small fortune to keep her, one might in all likelihood think of beauty first, to be followed quickly by wit, or that talent indispensable to the art of seduction known as charm. As appealing as it is, timing may not even be on the list.

Yet, of all the virtues a great courtesan had to possess, good timing was perhaps the most crucial. Indeed, her very existence depended on it. Had she not been able to move in perfect synchrony with history, no woman would ever have been able to enter the profession. Whether it was poverty or scandal that she faced, her genius was to turn difficult circumstances to immense profit and pleasure. She did the right thing at the right time.

Regarding survival, the best choice to be made at one moment will, in another period, not even be a good choice. All things considered, it would not be a wise choice for most women to become courtesans today. Indeed, the ingredients required to become one no longer exist. A courtesan occupied a precise place in society; as independent as she was, circumstance defined her. If, in the middle of the twentieth century,

Helen Gurley Brown, future editor in chief of Cosmopolitan magazine, was kept by a wealthy movie producer, she was not called a courtesan. Like the atmosphere that created the tradition, the word had already become an anachronism.

Just as Venus arose from the sea instead of a lake or a river, the courtesan emerged from a very particular medium. The waters of her birth, salted by the bitter tears of women who were condemned to penury and by those of wealthy and poor women alike who lamented the rules that limited and constrained their erotic lives, were made up of a perfect blend of injustice and prudery. The genius of the courtesan was in how she turned the same ingredients to her advantage. Considering the distribution of power between men and women in the times during which she lived, to say that she turned the tables would be an understatement. If we ponder very long the fact, for instance, that La Belle Otro, the famous courtesan of the Second Empire, successfully demanded from one of her lovers the priceless long diamond necklace that had once belonged to the former queen, Marie-Antoinette, we may begin to appreciate the dimensions of the reversal. Yet exactly how this stunning victory was achieved remains a mystery.

Some clues are given to us in a story that Colette tells about a conversation she had while she was still performing in music halls with La Belle Otro. Thinking the young woman somewhat green, Otro offered her some advice. "There comes a time," she said, "with every man when he will open up his hand to you."

"But when is that?" Colette asked.

"When you twist his wrist," Otero replied.

Like many courtesans, Otero was known for her wit. Doubtless, that is why Colette remembered the dialogue. Indeed, the key we are seeking to the mystery is less in the content of Otero's answer than in the way it was given. She delivered her last line with consummate timing. And looking further at what she told her young protegee, it becomes quickly evident that the crucial phrase in her advice is not in the last line but in the first phrase, "There comes a time." The secret of her success was that she chose exactly the right moment to twist her lover's wrist.

We cannot know, but only surmise, that Otero would have been glad to tell Colette exactly how to recognize the right moment for doing anything. But those who have this talent rarely understand themselves how they know what they know. Rather than a technique that can be analyzed, the ability for good timing must be the product of a particularly intense relationship with the present. To speak of having an awareness of the present moment may seem strange, as if such an awareness should be common place. But in fact, since most of us, much of the time, are focused more on the past or the future than on what is here now, the ability is unusual.

This uniqueness may explain why courtesans were so often found at the cutting edge of new sensibilities. While she used time to her own advantage, the courtesan expanded the terrain of the imagination. Indeed, the fact that so often whenever culture made a daring turn, breaking old boundaries, flying in the face of convention, courtesans have been part of that history illustrates how time moves forward. In contrast to the conventional view, it is less by aiming yourself in the direction of the future that you will affect the tenor of your times than by immersing yourself in the present.

How did she develop her unique presence? At this point, we can only guess. But our guesses are educated. Early deprivation and fear for survival would have played major roles in the unfolding drama. Traumatic events, losses, and miseries can make every moment of life seem like a precious substance, not a drop of which should be missed. At the same time, narrow escapes and fortunate breaks can loosen the hold that well-laid plans have on the mind, serving to free events from any narrative plot that is too constricting.

And from this perhaps we can also begin to grasp why, aside from any efficacy, good timing is so attractive. Though you would not have been able to name the seemingly ephemeral effect she had of enlarging your consciousness, a courtesan's awareness of time might make you long for her in the same way that a mystic longs for God. Or, if you are devoutly secular, for what is still nascent in yourself.

Yet, as ephemeral as it may seem, this virtue means far less in the abstract than it does in the concrete example. So let us proceed, if not methodically, bit by bit, through many of the simpler expressions of good timing that are more plainly manifested in the lives of courtesans. This is, after all, hardly a dreary task. Known as a "good-time girl," the courtesan had to be able to make men laugh, which called on comic timing. To dress well, she had to know what to wear--and when. And for flirtation, of course, essential to all her other accomplishments, she had to have exquisite timing. There is almost nothing she did that did not require this virtue. But we begin with the activity most often associated with courtesans, perhaps because it is the one with which so many began their careers: dance.

The Way She Danced

It don't mean a thing, if you ain't got that swing.

--Cole Porter

The moment was legendary. Before the music began, no one had heard of her. But as she circled about the floor, her body moving up and down with a vitality memorable even today, every eye in the dance hall was on her. As the polka beat out its inexorable rhythms, the heat of attention only increased. When she and her partner stopped dancing, the inevitable crowd of men surrounded her. Because of the way she danced that night, her life would never be the same again.

Why was her dance so powerful? Philosophy pauses here. Though time is a fascinating concept, it pales when you think of this scene. Even to begin to answer the question, we will have to expand our vocabulary. Timing may serve to describe the ability to coordinate desire and circumstance, yet it fails to illuminate the mysterious bodily process by which these effects are achieved. For this purpose, we must explore the concept of rhythm, too.

Yet even this word needs some resuscitation. Perhaps because of the clock and metronome, in contemporary thought we have come to mistake rhythm for a simple mechanical activity. Even the dictionary makes this error, calling rhythm "a procedure with the patterned occurrence of a beat." But buried deeply within the entries, you can find the word "cadence", an older term, with an appealing gloss and a far more sensual patina. And listed third or fourth in the definitions of cadence there is an entry that serves this exploration well: "the pattern in which something is experienced."

Just think of the beat that underlies all that we do. Breathing, of course, is almost too obvious. As is lovemaking, abundantly clear. But there are also walking, eating, and even seeing, as the eyes dart about the room, or speaking, as impulses and desires swim past, surface, and slide away again. Whether by the subtle starts and stops of a conversation or the inescapably loud punctuation provided by a pair of cymbals, rhythm shapes and inspires every moment.

The rhythm at the heart of dance is the same as the one that informs all experience. The only way to move with a piece of music is to feel the rhythm as it expands into your hips, your legs, your arms, your feet. Think for instance of a line of Rockettes, or better yet, since many dancers from the Folies Bergeres became courtesans, a circle of chorus girls from that show. If one of them were to be off step, we would quickly sense her failure to feel the music. Her performance would lack more than tempo. The spirit of both the music and the dance would be missing, too. Her dance would be lackluster.

The great French actress known as Rosay, who studied music as a child, referred to rhythm as a form of energy. She used the word to describe the way actors go beyond merely pretending to feel what the characters in a play are supposed to feel. Instead, she said, an actor must actually experience the feeling. If the courtesan was, to some degree, always acting, her success depended on how well she could act, that is, on whether or not she actually experienced the feelings she radiated. But this must have been what Rosay meant. When you find the right tempo for any activity, whether it is eating or walking, talking or making love, you have also found the capacity to feel.

In her Memoirs, Celeste Venard, the dancer known as Mogador, claimed that she never wanted to be a courtesan. Even so, she must have played the role with feeling. The way she danced was so inspiring that when she performed the polka in the crowded dance hall called the Bal Mabille, she made her reputation in a single night. Though we can only imagine this famous dance now, several clues to the charm it must have had remain for us. There is, for instance, the series of etchings and paintings that Toulouse-Lautrec did of dance-hall life. He often depicted a dancer and courtesan known then as La Goulue, who was famous for dancing the can-can. At public dance hall, women would compete with each other over who could kick her legs higher and thus reveal more of what was underneath her skirts. La Goulue became famous as the undisputed winner. The thrill was, of course, to be able to see so far beneath the skirts of the dancers, who were not always wearing pantaloons. The ardor of the revelation was only increased with the progressively rapid, excited beat of the music to which each kick was timed.

In one of the posters Toulouse-Lautrec designed for the Moulin Rouge, he portrays La Goulue with an expression that is neither bawdy nor frivolous. As she balances on one leg and lifts her right leg high, she stares intently into space, as if concentrating on her art. She is clearly a woman serious about her work. Of course, even if at other moments she laughed, she had to be focused at this moment. She was earning her living. But Lautrec has captured another energy altogether in the lower half of her body. Below her waist, a froth of lace and lingerie gushes forth, as if out of a hidden source within her, threatening to fill the room.

Timing

Ripeness is all.

--William Shakespeare

It is always wise to begin with a mystery. Translucent, invisible, continually in motion, timing is difficult to discern and just as hard to describe. Nevertheless, the appeal of anyone who possesses this virtue is certainly palpable. Let us suppose, for example, that in the bare beginnings of the twentieth century, in say 1905, you chance to attend a party given at the country estate of Etienne Balsan. You may find yourself smiling at a woman who passes you on the stairs. And though you have not met her yet, you realize you are wishing that you will soon. Later, when you see her talking with a small group across the room, you are almost embarrassed at how often your eyes wander in her direction. What is it about her? She is good-looking but not extraordinarily so. No, it is something else that draws you. An air of indefinable excitement that seems to radiate out in waves around her.

You see that her presence affects those who are standing near her. The atmosphere in that part of the room is distinctly electric. The way she is dressed gives you a clue. She is wearing what looks like a man's riding jacket, only cut to follow the lines of her small body. Though the look is eccentric, the style seems to place her at the very edge of the present moment. And the look in her eyes, almost mocking, gives you the intriguing impression that she is seeing just past the precipice of what is happening now, that she is, in fact, fully aware of (and more than ready for) the moment which has not quite arrived yet. Still, she has not given herself to the future. Fully here, her movements and gestures are perfectly syncopated with the soundless rhythm to which you suddenly realize the whole room is moving. As the air fairly crackles around her, you begin to believe that she is helping to bring new possibilities into being, including the new worlds that seem to have emerged in your own imagination since the first moment you laid eyes on her. Only at the end of the day, do you learn that she is your host's lover, a young woman named Gabrielle. When, later, you hear her name spoken all over Paris, you are not so surprised. What was it about her that was so extraordinary? Her timing was brilliant.

Still, as compelling as a woman with good timing is, the question remains: Why should this virtue be placed first in our catalogue? Asked what could make a woman so attractive that a man would be willing to spend a small fortune to keep her, one might in all likelihood think of beauty first, to be followed quickly by wit, or that talent indispensable to the art of seduction known as charm. As appealing as it is, timing may not even be on the list.

Yet, of all the virtues a great courtesan had to possess, good timing was perhaps the most crucial. Indeed, her very existence depended on it. Had she not been able to move in perfect synchrony with history, no woman would ever have been able to enter the profession. Whether it was poverty or scandal that she faced, her genius was to turn difficult circumstances to immense profit and pleasure. She did the right thing at the right time.

Regarding survival, the best choice to be made at one moment will, in another period, not even be a good choice. All things considered, it would not be a wise choice for most women to become courtesans today. Indeed, the ingredients required to become one no longer exist. A courtesan occupied a precise place in society; as independent as she was, circumstance defined her. If, in the middle of the twentieth century,

Helen Gurley Brown, future editor in chief of Cosmopolitan magazine, was kept by a wealthy movie producer, she was not called a courtesan. Like the atmosphere that created the tradition, the word had already become an anachronism.

Just as Venus arose from the sea instead of a lake or a river, the courtesan emerged from a very particular medium. The waters of her birth, salted by the bitter tears of women who were condemned to penury and by those of wealthy and poor women alike who lamented the rules that limited and constrained their erotic lives, were made up of a perfect blend of injustice and prudery. The genius of the courtesan was in how she turned the same ingredients to her advantage. Considering the distribution of power between men and women in the times during which she lived, to say that she turned the tables would be an understatement. If we ponder very long the fact, for instance, that La Belle Otro, the famous courtesan of the Second Empire, successfully demanded from one of her lovers the priceless long diamond necklace that had once belonged to the former queen, Marie-Antoinette, we may begin to appreciate the dimensions of the reversal. Yet exactly how this stunning victory was achieved remains a mystery.

Some clues are given to us in a story that Colette tells about a conversation she had while she was still performing in music halls with La Belle Otro. Thinking the young woman somewhat green, Otro offered her some advice. "There comes a time," she said, "with every man when he will open up his hand to you."

"But when is that?" Colette asked.

"When you twist his wrist," Otero replied.

Like many courtesans, Otero was known for her wit. Doubtless, that is why Colette remembered the dialogue. Indeed, the key we are seeking to the mystery is less in the content of Otero's answer than in the way it was given. She delivered her last line with consummate timing. And looking further at what she told her young protegee, it becomes quickly evident that the crucial phrase in her advice is not in the last line but in the first phrase, "There comes a time." The secret of her success was that she chose exactly the right moment to twist her lover's wrist.

We cannot know, but only surmise, that Otero would have been glad to tell Colette exactly how to recognize the right moment for doing anything. But those who have this talent rarely understand themselves how they know what they know. Rather than a technique that can be analyzed, the ability for good timing must be the product of a particularly intense relationship with the present. To speak of having an awareness of the present moment may seem strange, as if such an awareness should be common place. But in fact, since most of us, much of the time, are focused more on the past or the future than on what is here now, the ability is unusual.

This uniqueness may explain why courtesans were so often found at the cutting edge of new sensibilities. While she used time to her own advantage, the courtesan expanded the terrain of the imagination. Indeed, the fact that so often whenever culture made a daring turn, breaking old boundaries, flying in the face of convention, courtesans have been part of that history illustrates how time moves forward. In contrast to the conventional view, it is less by aiming yourself in the direction of the future that you will affect the tenor of your times than by immersing yourself in the present.

How did she develop her unique presence? At this point, we can only guess. But our guesses are educated. Early deprivation and fear for survival would have played major roles in the unfolding drama. Traumatic events, losses, and miseries can make every moment of life seem like a precious substance, not a drop of which should be missed. At the same time, narrow escapes and fortunate breaks can loosen the hold that well-laid plans have on the mind, serving to free events from any narrative plot that is too constricting.

And from this perhaps we can also begin to grasp why, aside from any efficacy, good timing is so attractive. Though you would not have been able to name the seemingly ephemeral effect she had of enlarging your consciousness, a courtesan's awareness of time might make you long for her in the same way that a mystic longs for God. Or, if you are devoutly secular, for what is still nascent in yourself.

Yet, as ephemeral as it may seem, this virtue means far less in the abstract than it does in the concrete example. So let us proceed, if not methodically, bit by bit, through many of the simpler expressions of good timing that are more plainly manifested in the lives of courtesans. This is, after all, hardly a dreary task. Known as a "good-time girl," the courtesan had to be able to make men laugh, which called on comic timing. To dress well, she had to know what to wear--and when. And for flirtation, of course, essential to all her other accomplishments, she had to have exquisite timing. There is almost nothing she did that did not require this virtue. But we begin with the activity most often associated with courtesans, perhaps because it is the one with which so many began their careers: dance.

The Way She Danced

It don't mean a thing, if you ain't got that swing.

--Cole Porter

The moment was legendary. Before the music began, no one had heard of her. But as she circled about the floor, her body moving up and down with a vitality memorable even today, every eye in the dance hall was on her. As the polka beat out its inexorable rhythms, the heat of attention only increased. When she and her partner stopped dancing, the inevitable crowd of men surrounded her. Because of the way she danced that night, her life would never be the same again.

Why was her dance so powerful? Philosophy pauses here. Though time is a fascinating concept, it pales when you think of this scene. Even to begin to answer the question, we will have to expand our vocabulary. Timing may serve to describe the ability to coordinate desire and circumstance, yet it fails to illuminate the mysterious bodily process by which these effects are achieved. For this purpose, we must explore the concept of rhythm, too.

Yet even this word needs some resuscitation. Perhaps because of the clock and metronome, in contemporary thought we have come to mistake rhythm for a simple mechanical activity. Even the dictionary makes this error, calling rhythm "a procedure with the patterned occurrence of a beat." But buried deeply within the entries, you can find the word "cadence", an older term, with an appealing gloss and a far more sensual patina. And listed third or fourth in the definitions of cadence there is an entry that serves this exploration well: "the pattern in which something is experienced."

Just think of the beat that underlies all that we do. Breathing, of course, is almost too obvious. As is lovemaking, abundantly clear. But there are also walking, eating, and even seeing, as the eyes dart about the room, or speaking, as impulses and desires swim past, surface, and slide away again. Whether by the subtle starts and stops of a conversation or the inescapably loud punctuation provided by a pair of cymbals, rhythm shapes and inspires every moment.

The rhythm at the heart of dance is the same as the one that informs all experience. The only way to move with a piece of music is to feel the rhythm as it expands into your hips, your legs, your arms, your feet. Think for instance of a line of Rockettes, or better yet, since many dancers from the Folies Bergeres became courtesans, a circle of chorus girls from that show. If one of them were to be off step, we would quickly sense her failure to feel the music. Her performance would lack more than tempo. The spirit of both the music and the dance would be missing, too. Her dance would be lackluster.

The great French actress known as Rosay, who studied music as a child, referred to rhythm as a form of energy. She used the word to describe the way actors go beyond merely pretending to feel what the characters in a play are supposed to feel. Instead, she said, an actor must actually experience the feeling. If the courtesan was, to some degree, always acting, her success depended on how well she could act, that is, on whether or not she actually experienced the feelings she radiated. But this must have been what Rosay meant. When you find the right tempo for any activity, whether it is eating or walking, talking or making love, you have also found the capacity to feel.

In her Memoirs, Celeste Venard, the dancer known as Mogador, claimed that she never wanted to be a courtesan. Even so, she must have played the role with feeling. The way she danced was so inspiring that when she performed the polka in the crowded dance hall called the Bal Mabille, she made her reputation in a single night. Though we can only imagine this famous dance now, several clues to the charm it must have had remain for us. There is, for instance, the series of etchings and paintings that Toulouse-Lautrec did of dance-hall life. He often depicted a dancer and courtesan known then as La Goulue, who was famous for dancing the can-can. At public dance hall, women would compete with each other over who could kick her legs higher and thus reveal more of what was underneath her skirts. La Goulue became famous as the undisputed winner. The thrill was, of course, to be able to see so far beneath the skirts of the dancers, who were not always wearing pantaloons. The ardor of the revelation was only increased with the progressively rapid, excited beat of the music to which each kick was timed.

In one of the posters Toulouse-Lautrec designed for the Moulin Rouge, he portrays La Goulue with an expression that is neither bawdy nor frivolous. As she balances on one leg and lifts her right leg high, she stares intently into space, as if concentrating on her art. She is clearly a woman serious about her work. Of course, even if at other moments she laughed, she had to be focused at this moment. She was earning her living. But Lautrec has captured another energy altogether in the lower half of her body. Below her waist, a froth of lace and lingerie gushes forth, as if out of a hidden source within her, threatening to fill the room.

Recenzii

"Provocative and compelling, filled with Susan Griffin's typically wise and beautiful writing, The Book of The Courtesans rescues from near oblivian some of history's most outrageous and audacious women."

--Alice Walker, author of The Color Purple

--Alice Walker, author of The Color Purple

Descriere

Feminist writer Griffin takes a provocative look at the pleasure-filled world of the West's first female power brokers, whose lively liaisons brought them unspoken influence, wealth, and freedom. 45 illustrations throughout.