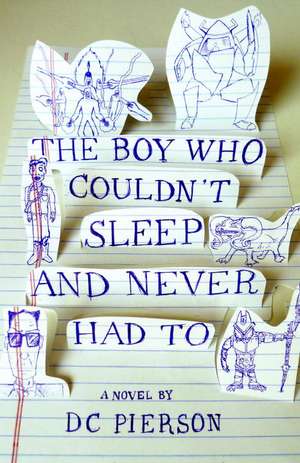

The Boy Who Couldn't Sleep and Never Had to

Autor D. C. Piersonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2009 – vârsta de la 14 până la 18 ani

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Alex Awards (2011), Green Mountain Book Award (2013)

When Darren Bennett meets Eric Lederer, there's an instant connection. They share a love of drawing, the bottom rung on the cruel high school social ladder and a pathological fear of girls. Then Eric reveals a secret: He doesn’t sleep. Ever. When word leaks out about Eric's condition, he and Darren find themselves on the run. Is it the government trying to tap into Eric’s mind, or something far darker? It could be that not sleeping is only part of what Eric's capable of, and the truth is both better and worse than they could ever imagine.

Preț: 91.36 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 137

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.48€ • 18.34$ • 14.55£

17.48€ • 18.34$ • 14.55£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307474612

ISBN-10: 0307474615

Pagini: 226

Dimensiuni: 135 x 202 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Locul publicării:New York, NY

ISBN-10: 0307474615

Pagini: 226

Dimensiuni: 135 x 202 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Locul publicării:New York, NY

Notă biografică

DC Pierson was born and raised in Phoenix, AZ. He graduated from NYU's Dramatic Writing Department in 2007 with a degree in writing for television. His comedy group DERRICK made a feature film called "Mystery Team." He publishes short stories and unsolicited opinions on his website, dcpierson.com. This is his first novel.

Extras

1

I’ve got a system to keep people from seeing what I’m drawing.

A thousand cartoons and TV shows and teen movies would lead you to believe that when you’re drawing something at your desk in school, a pretty girl is going to say “What are you drawing?” and you’ll tell her and she’ll go “That’s neat” and your artistry will reveal to her the secret sensitivity in your soul and she’ll leave her football-player boyfriend for you. These cartoons and TV shows and teen movies are wrong.

In my experience, a pretty girl never sees you drawing and goes “You’re an amazing artist.” In my experience a pretty girl sees you drawing and, if she says anything at all, she goes, “Wow, you’re a really good drawer.” Not drawer like where you put socks, but draw-er. Guys who are good at basketball are not described as excellent throwers, and dudes who are good at guitar are not called really good strummers, but somehow I’m a really good draw-er.

And the experience does not change based on what it is she catches you drawing in the margins of your math notebook or whatever. No matter how well you’re drawing it, there’s nothing good you can be drawing. You can’t win. If you’re drawing superheroes, that looks nerdy. If you’re drawing landscapes or things girls might actually like, like animals, that looks girly. If you’re drawing the female figure, you’re a pervert. If you’re drawing the male figure, you’re gay. If you’re drawing superheroes and you haven’t gotten around to drawing the masks or capes or whatever yet, you’re gay. Do yourself a favor: Don’t start with the muscles. Start with the rocketpack and work your way out. You’ll still be nerdy, but everybody knew that about you already. I mean, come on: you’re DRAWING.

And those “how-to-draw-comics” books? Fuck those books. Everybody saw those in their Scholastic book orders in second grade and now they assume I just ordered enough of those books, and that anyone could draw this well if they’d done the same. Well, they’re a little right. I did order like two of those books. And the first thing they teach you is this system of lines and shapes, to sketch out the bodies first before you fill in the details. Basically what you have before you start having anything that looks like anything is a page full of what looks like basketballs and potato sacks. The basketball-looking things are eventually gonna be heads and the potato sacks are eventually gonna be torsos, but when I was drawing based on those books, the guidelines would never really erase right and it always looked like all my characters’ limbs were built around a sack of potatoes with a superhero insignia printed on it, or like they’d just been nailed in the face with a superheated basketball. Anyway, the point is, fuck those books.

There’s this kid, Tony DiAvalo, who always makes a big show of being the kid who draws in class. He’ll use whatever time is left over at the end of the period and pull out his special pencils and his special pencil sharpener and this big fucking drawing pad and just start.

He’s good, I guess. Probably even good enough to justify all the supplies. But it’s just so goddamn showoff-y, and the things he picks to draw are just so inane. It’s all pop-culture stuff, never anything original. It’s always, like, one of those cartoon M&Ms except the M&M is wearing a doo-rag and smoking a joint and he’s written something underneath the M&M like “HUSTLIN’.” Kids think it’s hilarious. And I guess, if pressed, he would point to that joint and doo-rag as his “originality.” He’d probably have you believe he’s as original as someone who fills their notebooks with things they made up. All I know is he draws to be seen drawing, and he draws what people want to see. I guess I take back the statement that there’s nothing good you can be drawing: everybody seems to think preexisting cartoon characters smoking weed and counting money is pretty hilarious, and a good thing to hang in your locker.

One time his showiness got him in trouble and he got busted. Mrs. Cartwright the Spanish teacher saw three or four kids huddling around his pad in the last ten minutes of class when people are supposed to be working on their Spanish free-writing. They were behaving the way people usually do around Tony DiAvalo’s drawing pad, which is high-fiving each other, and Tony, and saying “Sick!” That’s way more excited than anybody ever is about Spanish free-writing, so Mrs. Cartwright rushed over, and saw on Tony’s pad an almost-finished depiction of Tommy from Rugrats as Scarface, complete with giant mountain of cocaine. She sent everybody back to their desks except for Tony, who she sent to the office, where he was written up for “advertising drug paraphernalia.” So now his M&Ms and his Spongebobs go jointless, though they’re still “HUSTLIN’.”

While I don’t pull out the big fucking pad, it’s not like I go behind a curtain or anything, either. I don’t make a big show of hiding what I’m drawing. That’s just as bad. I don’t cup my hand around the part of the notebook page or worksheet-back I’m drawing on. Made that mistake before. It just makes you look guilty. Someone is inevitably going to ask and you can’t say no because then it looks like you’re hiding something and when you do show them whatever you’re drawing it’s going to be interpreted with suspicion because it looks like you were hiding something. If this happens and what you’re drawing happens to be a girl, the kid you show it to will think it’s a girl in your class that you have a crush on. If this happens and you’re drawing a gun, the kid will think you want to shoot up the school. So I don’t hide it. Or I don’t make it look like I’m trying to hide it. Being super-obvious about hiding something is almost showing off. It’s almost worse. It’s like this fragile-genius thing I think would be disgusting. Like girls in the back of English class being very obvious about the fact that they’re writing tortured poetry. No one cares.

And that’s the thing, is that no one cares. No one cares but they will ask anyway, in this detached way, “What are you drawing?” and you know just by how they ask that they don’t care, and you wonder what the point is of explaining, because they don’t care and when you explain they won’t understand or even bother to try, but you’ll look like a creep if you don’t answer but you’re so upset by the fact of their even asking in this half-baked way that by the time you do answer you’ll come off like a huffy know-it-all, guaranteed, every time. So better, for everyone, to be subtle. Saves you from coming off weird and saves them their I-barely-give-a-shit-anyway energy.

I don’t get absorbed. I don’t hunch over and curl my tongue up like I’m super-concentrated. The time between when you’re finished with your work and class gets out would seem like the best time, because you can concentrate the most, but it’s actually the worst. I draw while the teacher is talking, because then everybody’s looking up at the front of the classroom, or at least they’re supposed to be. I look up periodically, just like everybody else. I jot down notes occasionally, just like everybody else. Every so often my pencil drifts over and draws the jawline of a face. Then it returns to its place and writes “GILDED AGE 1870–1890.” Then it drifts over again and draws a nose. Then it goes back and writes “COINED BY MARK TWAIN IN BOOK OF SAME NAME.” Then it puts a pair of sunglasses on the nose. I’m into sunglasses recently. They’re not as risky as eyes.

When there’s not a good reason for me to have my pencil up, I put it away. When that empty five to ten minutes at the end of class comes around where weaker men do their drawing and end up being interrogated by popular girls and pushy dudes, I pull out a book. I try to make it a book we were assigned, too. Fewer questions that way.

“What were you drawing?” somebody asks me when I’m four pages into The Great Gatsby, which we just went up to the front of the room to get our copies of.

“Huh?” I look up. Eric Lederer is standing over my desk.

“When Mrs. Amory was talking about our independent essay assignment. You were drawing something.”

“Oh yeah. It’s nothing.”

Eric Lederer and I have never talked, I don’t think. All I know about him is he looks like a nerd, turns everything in super-on-time if not early, and knows every answer to every question always and is not shy about raising his hand to prove it. Which makes him a nerd I guess. Cecelia Martin must know more about him than I do, because she’s looking at him like he just blew up a school bus and whispering to two girls next to her across the room. Looks like something along the lines of “That guy just blew up a school bus.”

“Can I see?” he asks. Having never paid that much attention to him, I haven’t until just right now noticed that there’s something strange about him. It takes me a second but I realize what it is: he’s standing really still. Right in front of my desk, both feet planted. No one stands this awkwardly sure of themselves except characters in my drawings, staring straight ahead with their arms at their sides, because when they start to move around I start to realize that those drawing books might have a point about form and motion, even if what their tips usually get me is a bunch of basketball-burned sack-bodied heroes.

“Sure,” I say. I open my notebook. Folded up inside is the bright orange sheet with the criteria for our independent essay assignment. The bright orange color will be a big help when I’m digging through my backpack the night before the essay is due trying to find the criteria so I know what the hell to write, the whole time swearing to myself I’m going to get some sort of organization thing going, but knowing I won’t as long as teachers keep printing the important stuff on brightly colored paper that stands out even when it’s shoved into my backpack with a roughness that says “I’ll never need this again!”

I smooth out the paper and hand it to Eric. In the bottom right-hand corner of the page, underneath big bold letters that say “WORKS CITED IN PROPER MLA FORMAT!!!” two men in suits and dark sunglasses are restraining a cybernetic caveman with electrified lassos.

“Nice monkey,” I expect Eric to say. Even with the best intentions people always get what I’m drawing wrong, and admittedly the caveman looks kind of monkey-ish.

“Nice cyborg,” Eric says.

“Thanks,” I say.

“Is this going to be a comic book?” he asks.

“No,” I say, “I was just doodling.”

“Oh,” Eric says.

I was trying to be dismissive because Eric being genuinely interested seems about as bad as Bret Embler or Carter Buehl being mock-interested. Here somebody across the room is staring at him like he blew up a bus, and I wonder if he has a reputation that I don’t know about that’s rubbing off on me just by being seen talking to him that will get me lots more attention from idiots. But I may have embarrassed myself just as much by using the word “doodling.” I look around, sort of like “does anyone know this kid? I don’t,” and see that Cecelia and her friends are still looking at Eric like, “That’s him, Officer, he’s the one who laughed when those kids who thought they were going to school went to Heaven instead.”

“You know that kid that always draws cartoon characters?” Eric says.

“Tony. Yeah.” He’s going to suggest Tony and I would make good friends since we both draw. Lindsay Skinner once told me Tony and I should be “drawing buddies.” Lindsay will never know what that remark cost her, and what it cost her was me asking her out, something I had been psyching myself up to do for weeks until the “drawing buddies” comment. So I didn’t get to stand in front of Lindsay’s locker and stutter out one of the eighty-five variations on “Do you wanna go do something sometime” I’d been weighing the pros and cons of, and Lindsay didn’t get to shoot me down.

“Do you think he’s good?”

“Tony’s alright, yeah.”

“Oh,” Eric says, the same way he said it when I told him I wasn’t drawing a comic book. “I think he’s awful.”

“Really?” I look around, this time to see if any of Tony’s friends are around. Then I realize Tony doesn’t really have friends, just what I like to think of as freak-show admirers.

“Yeah,” Eric says. “He never draws anything original. You originated these characters, right?”

“I mean, they’re just?.?.?.?y’know?.?.?.?doodles, but yeah.”

“I think that’s great,” Eric says. “I couldn’t draw anything, original or otherwise, if my life depended on it.”

“Yeah?” I say. “That sucks.”

“It does,” Eric says. He folds the sheet back up the way it was and gives it back to me.

The bell rings. Eric hustles back to his seat to get his stuff. I throw my notebook and The Great Gatsby in my bag and I’m out the door when one of Cecelia’s friends, Jen, catches up with me.

“Hey,” Jen says. “Do you?.?.?.?talk to that kid?”

I shrug. “I dunno,” I say. “Not really.”

“Oh,” she says, “never mind,” and starts off down the hallway.

Eric comes out of the classroom, his backpack way too high on his back.

“See you tomorrow,” he says. “I know it’s not a comic, but you should consider trying your hand at one. Seems like you have the chops, drawing-wise, along with the originality to not just sketch other people’s copyrighted material plus drugs.”

“It’s not a comic, but, uhm,” I say. “It’s actually a movie trilogy and a series of novels.”

“Awesome,” Eric says, breaking his weird stillness to hop just a little on his toes. It’s geeky but it’s pretty much the way I’d want somebody to react if they were the first person I told I was planning a movie trilogy and a series of novels. Eric is the first person. He says “awesome” again and we go off to fourth period in opposite directions.

“What’s it about?”

Eric is standing over me again the next day towards the end of third period. No “hi” or “what’s up” or anything, like our conversation from yesterday never ended.

“The movie trilogy and series of novels.”

“It’s sort of a lot to like, go into,” I say. “You know the loading dock by the auditorium?”

I’ve got a system to keep people from seeing what I’m drawing.

A thousand cartoons and TV shows and teen movies would lead you to believe that when you’re drawing something at your desk in school, a pretty girl is going to say “What are you drawing?” and you’ll tell her and she’ll go “That’s neat” and your artistry will reveal to her the secret sensitivity in your soul and she’ll leave her football-player boyfriend for you. These cartoons and TV shows and teen movies are wrong.

In my experience, a pretty girl never sees you drawing and goes “You’re an amazing artist.” In my experience a pretty girl sees you drawing and, if she says anything at all, she goes, “Wow, you’re a really good drawer.” Not drawer like where you put socks, but draw-er. Guys who are good at basketball are not described as excellent throwers, and dudes who are good at guitar are not called really good strummers, but somehow I’m a really good draw-er.

And the experience does not change based on what it is she catches you drawing in the margins of your math notebook or whatever. No matter how well you’re drawing it, there’s nothing good you can be drawing. You can’t win. If you’re drawing superheroes, that looks nerdy. If you’re drawing landscapes or things girls might actually like, like animals, that looks girly. If you’re drawing the female figure, you’re a pervert. If you’re drawing the male figure, you’re gay. If you’re drawing superheroes and you haven’t gotten around to drawing the masks or capes or whatever yet, you’re gay. Do yourself a favor: Don’t start with the muscles. Start with the rocketpack and work your way out. You’ll still be nerdy, but everybody knew that about you already. I mean, come on: you’re DRAWING.

And those “how-to-draw-comics” books? Fuck those books. Everybody saw those in their Scholastic book orders in second grade and now they assume I just ordered enough of those books, and that anyone could draw this well if they’d done the same. Well, they’re a little right. I did order like two of those books. And the first thing they teach you is this system of lines and shapes, to sketch out the bodies first before you fill in the details. Basically what you have before you start having anything that looks like anything is a page full of what looks like basketballs and potato sacks. The basketball-looking things are eventually gonna be heads and the potato sacks are eventually gonna be torsos, but when I was drawing based on those books, the guidelines would never really erase right and it always looked like all my characters’ limbs were built around a sack of potatoes with a superhero insignia printed on it, or like they’d just been nailed in the face with a superheated basketball. Anyway, the point is, fuck those books.

There’s this kid, Tony DiAvalo, who always makes a big show of being the kid who draws in class. He’ll use whatever time is left over at the end of the period and pull out his special pencils and his special pencil sharpener and this big fucking drawing pad and just start.

He’s good, I guess. Probably even good enough to justify all the supplies. But it’s just so goddamn showoff-y, and the things he picks to draw are just so inane. It’s all pop-culture stuff, never anything original. It’s always, like, one of those cartoon M&Ms except the M&M is wearing a doo-rag and smoking a joint and he’s written something underneath the M&M like “HUSTLIN’.” Kids think it’s hilarious. And I guess, if pressed, he would point to that joint and doo-rag as his “originality.” He’d probably have you believe he’s as original as someone who fills their notebooks with things they made up. All I know is he draws to be seen drawing, and he draws what people want to see. I guess I take back the statement that there’s nothing good you can be drawing: everybody seems to think preexisting cartoon characters smoking weed and counting money is pretty hilarious, and a good thing to hang in your locker.

One time his showiness got him in trouble and he got busted. Mrs. Cartwright the Spanish teacher saw three or four kids huddling around his pad in the last ten minutes of class when people are supposed to be working on their Spanish free-writing. They were behaving the way people usually do around Tony DiAvalo’s drawing pad, which is high-fiving each other, and Tony, and saying “Sick!” That’s way more excited than anybody ever is about Spanish free-writing, so Mrs. Cartwright rushed over, and saw on Tony’s pad an almost-finished depiction of Tommy from Rugrats as Scarface, complete with giant mountain of cocaine. She sent everybody back to their desks except for Tony, who she sent to the office, where he was written up for “advertising drug paraphernalia.” So now his M&Ms and his Spongebobs go jointless, though they’re still “HUSTLIN’.”

While I don’t pull out the big fucking pad, it’s not like I go behind a curtain or anything, either. I don’t make a big show of hiding what I’m drawing. That’s just as bad. I don’t cup my hand around the part of the notebook page or worksheet-back I’m drawing on. Made that mistake before. It just makes you look guilty. Someone is inevitably going to ask and you can’t say no because then it looks like you’re hiding something and when you do show them whatever you’re drawing it’s going to be interpreted with suspicion because it looks like you were hiding something. If this happens and what you’re drawing happens to be a girl, the kid you show it to will think it’s a girl in your class that you have a crush on. If this happens and you’re drawing a gun, the kid will think you want to shoot up the school. So I don’t hide it. Or I don’t make it look like I’m trying to hide it. Being super-obvious about hiding something is almost showing off. It’s almost worse. It’s like this fragile-genius thing I think would be disgusting. Like girls in the back of English class being very obvious about the fact that they’re writing tortured poetry. No one cares.

And that’s the thing, is that no one cares. No one cares but they will ask anyway, in this detached way, “What are you drawing?” and you know just by how they ask that they don’t care, and you wonder what the point is of explaining, because they don’t care and when you explain they won’t understand or even bother to try, but you’ll look like a creep if you don’t answer but you’re so upset by the fact of their even asking in this half-baked way that by the time you do answer you’ll come off like a huffy know-it-all, guaranteed, every time. So better, for everyone, to be subtle. Saves you from coming off weird and saves them their I-barely-give-a-shit-anyway energy.

I don’t get absorbed. I don’t hunch over and curl my tongue up like I’m super-concentrated. The time between when you’re finished with your work and class gets out would seem like the best time, because you can concentrate the most, but it’s actually the worst. I draw while the teacher is talking, because then everybody’s looking up at the front of the classroom, or at least they’re supposed to be. I look up periodically, just like everybody else. I jot down notes occasionally, just like everybody else. Every so often my pencil drifts over and draws the jawline of a face. Then it returns to its place and writes “GILDED AGE 1870–1890.” Then it drifts over again and draws a nose. Then it goes back and writes “COINED BY MARK TWAIN IN BOOK OF SAME NAME.” Then it puts a pair of sunglasses on the nose. I’m into sunglasses recently. They’re not as risky as eyes.

When there’s not a good reason for me to have my pencil up, I put it away. When that empty five to ten minutes at the end of class comes around where weaker men do their drawing and end up being interrogated by popular girls and pushy dudes, I pull out a book. I try to make it a book we were assigned, too. Fewer questions that way.

“What were you drawing?” somebody asks me when I’m four pages into The Great Gatsby, which we just went up to the front of the room to get our copies of.

“Huh?” I look up. Eric Lederer is standing over my desk.

“When Mrs. Amory was talking about our independent essay assignment. You were drawing something.”

“Oh yeah. It’s nothing.”

Eric Lederer and I have never talked, I don’t think. All I know about him is he looks like a nerd, turns everything in super-on-time if not early, and knows every answer to every question always and is not shy about raising his hand to prove it. Which makes him a nerd I guess. Cecelia Martin must know more about him than I do, because she’s looking at him like he just blew up a school bus and whispering to two girls next to her across the room. Looks like something along the lines of “That guy just blew up a school bus.”

“Can I see?” he asks. Having never paid that much attention to him, I haven’t until just right now noticed that there’s something strange about him. It takes me a second but I realize what it is: he’s standing really still. Right in front of my desk, both feet planted. No one stands this awkwardly sure of themselves except characters in my drawings, staring straight ahead with their arms at their sides, because when they start to move around I start to realize that those drawing books might have a point about form and motion, even if what their tips usually get me is a bunch of basketball-burned sack-bodied heroes.

“Sure,” I say. I open my notebook. Folded up inside is the bright orange sheet with the criteria for our independent essay assignment. The bright orange color will be a big help when I’m digging through my backpack the night before the essay is due trying to find the criteria so I know what the hell to write, the whole time swearing to myself I’m going to get some sort of organization thing going, but knowing I won’t as long as teachers keep printing the important stuff on brightly colored paper that stands out even when it’s shoved into my backpack with a roughness that says “I’ll never need this again!”

I smooth out the paper and hand it to Eric. In the bottom right-hand corner of the page, underneath big bold letters that say “WORKS CITED IN PROPER MLA FORMAT!!!” two men in suits and dark sunglasses are restraining a cybernetic caveman with electrified lassos.

“Nice monkey,” I expect Eric to say. Even with the best intentions people always get what I’m drawing wrong, and admittedly the caveman looks kind of monkey-ish.

“Nice cyborg,” Eric says.

“Thanks,” I say.

“Is this going to be a comic book?” he asks.

“No,” I say, “I was just doodling.”

“Oh,” Eric says.

I was trying to be dismissive because Eric being genuinely interested seems about as bad as Bret Embler or Carter Buehl being mock-interested. Here somebody across the room is staring at him like he blew up a bus, and I wonder if he has a reputation that I don’t know about that’s rubbing off on me just by being seen talking to him that will get me lots more attention from idiots. But I may have embarrassed myself just as much by using the word “doodling.” I look around, sort of like “does anyone know this kid? I don’t,” and see that Cecelia and her friends are still looking at Eric like, “That’s him, Officer, he’s the one who laughed when those kids who thought they were going to school went to Heaven instead.”

“You know that kid that always draws cartoon characters?” Eric says.

“Tony. Yeah.” He’s going to suggest Tony and I would make good friends since we both draw. Lindsay Skinner once told me Tony and I should be “drawing buddies.” Lindsay will never know what that remark cost her, and what it cost her was me asking her out, something I had been psyching myself up to do for weeks until the “drawing buddies” comment. So I didn’t get to stand in front of Lindsay’s locker and stutter out one of the eighty-five variations on “Do you wanna go do something sometime” I’d been weighing the pros and cons of, and Lindsay didn’t get to shoot me down.

“Do you think he’s good?”

“Tony’s alright, yeah.”

“Oh,” Eric says, the same way he said it when I told him I wasn’t drawing a comic book. “I think he’s awful.”

“Really?” I look around, this time to see if any of Tony’s friends are around. Then I realize Tony doesn’t really have friends, just what I like to think of as freak-show admirers.

“Yeah,” Eric says. “He never draws anything original. You originated these characters, right?”

“I mean, they’re just?.?.?.?y’know?.?.?.?doodles, but yeah.”

“I think that’s great,” Eric says. “I couldn’t draw anything, original or otherwise, if my life depended on it.”

“Yeah?” I say. “That sucks.”

“It does,” Eric says. He folds the sheet back up the way it was and gives it back to me.

The bell rings. Eric hustles back to his seat to get his stuff. I throw my notebook and The Great Gatsby in my bag and I’m out the door when one of Cecelia’s friends, Jen, catches up with me.

“Hey,” Jen says. “Do you?.?.?.?talk to that kid?”

I shrug. “I dunno,” I say. “Not really.”

“Oh,” she says, “never mind,” and starts off down the hallway.

Eric comes out of the classroom, his backpack way too high on his back.

“See you tomorrow,” he says. “I know it’s not a comic, but you should consider trying your hand at one. Seems like you have the chops, drawing-wise, along with the originality to not just sketch other people’s copyrighted material plus drugs.”

“It’s not a comic, but, uhm,” I say. “It’s actually a movie trilogy and a series of novels.”

“Awesome,” Eric says, breaking his weird stillness to hop just a little on his toes. It’s geeky but it’s pretty much the way I’d want somebody to react if they were the first person I told I was planning a movie trilogy and a series of novels. Eric is the first person. He says “awesome” again and we go off to fourth period in opposite directions.

“What’s it about?”

Eric is standing over me again the next day towards the end of third period. No “hi” or “what’s up” or anything, like our conversation from yesterday never ended.

“The movie trilogy and series of novels.”

“It’s sort of a lot to like, go into,” I say. “You know the loading dock by the auditorium?”

Recenzii

“Funny as hell. . . . The ribald humor of a Judd Apatow movie married to a science-fiction-fantasy spectacle.”—Kirkus

“A witty coming-of-age novel. . . . In Darren and Eric, Pierson has created two engaging and memorable co-conspirators and co-protagonists.”—Booklist

"Charmingly honest and honestly funny. Nails what it's like to be a geeky teenage male, right down to the Agtranian Berserkers." —Max Barry, author of Company

"In a smart, funny and endlessly imaginative debut, the voluminously talented DC Pierson shows keen insight into the rocky emotional terrain of adolescence and the nuances of geek culture. Pierson has a sharp eye for the way teenagers think, talk and behave. The scope and depth of the novel's ambition don't become apparent until a riveting final third that radically reinvents the narrative as a sly, Unbreakable-style exercise in genre deconstruction. Pierson has written a trenchant, briskly readable and ultimately sad novel about the greatest, most fantastical and mind-bending adventure of all: growing up."—Nathan Rabin, Head Writer, The A.V. Club, author, The Big Rewind: A Memoir Brought To You By Pop Culture

"Awesome stuff: great jokes, shocking twists, cyborgs. There's even some sex. It's fast-paced and funny and you should definitely check it out."--Simon Rich, author of Free-Range Chickens

“A witty coming-of-age novel. . . . In Darren and Eric, Pierson has created two engaging and memorable co-conspirators and co-protagonists.”—Booklist

"Charmingly honest and honestly funny. Nails what it's like to be a geeky teenage male, right down to the Agtranian Berserkers." —Max Barry, author of Company

"In a smart, funny and endlessly imaginative debut, the voluminously talented DC Pierson shows keen insight into the rocky emotional terrain of adolescence and the nuances of geek culture. Pierson has a sharp eye for the way teenagers think, talk and behave. The scope and depth of the novel's ambition don't become apparent until a riveting final third that radically reinvents the narrative as a sly, Unbreakable-style exercise in genre deconstruction. Pierson has written a trenchant, briskly readable and ultimately sad novel about the greatest, most fantastical and mind-bending adventure of all: growing up."—Nathan Rabin, Head Writer, The A.V. Club, author, The Big Rewind: A Memoir Brought To You By Pop Culture

"Awesome stuff: great jokes, shocking twists, cyborgs. There's even some sex. It's fast-paced and funny and you should definitely check it out."--Simon Rich, author of Free-Range Chickens

Descriere

Pierson presents this wildly original and hilarious debut novel about the unintended consequences of big imaginations.

Premii

- Alex Awards Winner, 2011

- Green Mountain Book Award Nominee, 2013