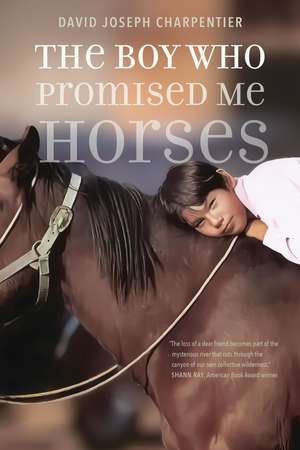

The Boy Who Promised Me Horses

Autor David Joseph Charpentier Cuvânt înainte de He'seota'e Mineren Limba Engleză Paperback – mai 2024

From the shock of moving from a bucolic Minnesota college to teach at a small, remote reservation school in eastern Montana, Charpentier details the complex and emotional challenges of Indigenous education in the United States. Although he intended his teaching tenure at St. Labre to be short, Charpentier’s involvement with the school has extended past thirty years. Unlike many white teachers who came and left the reservation, Charpentier has remained committed to the potentialities of Indigenous education, motivated by the early friendship he formed with Prairie Chief, who taught him lessons far and wide, from dealing with buffalo while riding a horse to coping with student dropouts he would never see again.

Told through episodic experiences, the story takes a journey back in time as Charpentier searches for answers to Prairie Chief’s life. As he sits on top of the sledding hill near the cemetery where Prairie Chief is buried, Charpentier finds solace in the memories of their shared (mis)adventures and their mutual respect, hard won through the challenges of educational and cultural mistrust.

Preț: 138.99 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 208

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.60€ • 27.77$ • 22.01£

26.60€ • 27.77$ • 22.01£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Livrare express 27 februarie-05 martie pentru 50.20 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781496238078

ISBN-10: 1496238079

Pagini: 324

Ilustrații: 20 photographs

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Editura: BISON BOOKS

Colecția Bison Books

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 1496238079

Pagini: 324

Ilustrații: 20 photographs

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Editura: BISON BOOKS

Colecția Bison Books

Locul publicării:United States

Notă biografică

David Joseph Charpentier is the director of St. Labre Indian School’s Alumni Support Program and executive director of the Bridge Foundation. For more information about the author, visit davidjcharpentier.com.

Extras

1

As Brief as His Life

2010

All I knew of Maurice Prairie Chief ’s death were the scarce details told to

me at the time, small bits I struggled to piece together over the ten years

since he was killed, since I sat and cried on the sledding hill below the

cemetery. “He tried to outrun a train in Missouri” is what Theodore Blindwoman

had said the night I found out.

One day I felt the need to learn more. I typed “Missouri train Maurice

Prairie Chief dead” into the Google search and pressed enter, and the

story appeared—easy as that. I didn’t even know it existed. (Google wasn’t

around when it happened.) But maybe I wasn’t ready until all this time

had passed, ready for the hard part I sensed was coming. It was archived

on the website of the Jefferson City (mo) News Tribune. The headline read,

“Two killed when train hits car.” I clicked print, and as I sat and waited,

the fracturing I had held off for years began again.

I thought I’d said goodbye to Maurice Prairie Chief five years before he

died, when I resigned from St. Labre Indian School in Ashland, Montana,

to pursue a master’s degree at the university in Missoula. On the evening I

left, with late-August shadows creeping across the road in front of Maurice’s

house in The Village, the setting sun shone into eyes that revealed nothing

to me. I thought I would never see him again.

While in Missoula, I began journaling about my four years as a high

school English teacher on the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation. Most

entries evolved into accounts of Maurice. I guess I hoped my friendship

had changed his life, and I searched for evidence of this in my stories, or I

sought at least to prove there was meaning to what otherwise were years

of my life that seemed directionless and wasted.

As life tends to drag us to places we don’t foresee, it can also put us back

in places we thought we were done with. I returned to Ashland a year later.

I had met a woman in Missoula, married her over the summer, and brought

her back with me to the reservation. But Maurice didn’t seem to like her

and began avoiding me. He also started skipping school. I realized then

that I could not save him, and I dreaded the end of his story, or I realized

there’d be no end and I was only reaching into his life clumsily without

really touching it. I couldn’t decide which was worse. Of course, I was

wrong. There was an end. And it was even worse. Although no one at the

time seemed to know the details to explain what had happened.

The article was as brief as his life, consisting of just seventy-one words

written in three fleeting paragraphs, answering the who, what, when, where,

and how. It opened with “Two people died when their car pulled around

a crossing arm and was hit by a train.” This sentence contained information

I hadn’t heard. I was told his car was hit by a train but not as it pulled

around a crossing arm.

I learned more. Maurice was not the driver. I didn’t recognize the other

name (so I left that person out of this story). Maurice’s two-word last name

must have confused the reporter, who shortened Prairie to P and treated

it like a middle initial: “Maurice P. Chief, of Risco,” which was strange to

read, given that he had lived all but a few months of his life in Ashland,

Montana. Maurice was not from Risco, not from Missouri.

For some reason, I found comfort in learning that Maurice wasn’t behind

the wheel. Not that he wouldn’t have tried to get around a crossing arm—he

was reckless and daring, always with a smile on his face when speed and

danger were involved—but I had let him drive my Ford Ranger xlt in the

forests around Ashland when he was ten. I knew he had skills.

No, I’m convinced Maurice would have made it through.

Both victims were pronounced dead at the scene of the accident. Maurice

died shortly before midnight on Saturday, March 13, 1999, one year to the

day before my daughter, Sarah, was born. He was seventeen.

The last line read, “No one was injured aboard the southbound Union

Pacific freight train.”

What was missing were the whys.

As Brief as His Life

2010

All I knew of Maurice Prairie Chief ’s death were the scarce details told to

me at the time, small bits I struggled to piece together over the ten years

since he was killed, since I sat and cried on the sledding hill below the

cemetery. “He tried to outrun a train in Missouri” is what Theodore Blindwoman

had said the night I found out.

One day I felt the need to learn more. I typed “Missouri train Maurice

Prairie Chief dead” into the Google search and pressed enter, and the

story appeared—easy as that. I didn’t even know it existed. (Google wasn’t

around when it happened.) But maybe I wasn’t ready until all this time

had passed, ready for the hard part I sensed was coming. It was archived

on the website of the Jefferson City (mo) News Tribune. The headline read,

“Two killed when train hits car.” I clicked print, and as I sat and waited,

the fracturing I had held off for years began again.

I thought I’d said goodbye to Maurice Prairie Chief five years before he

died, when I resigned from St. Labre Indian School in Ashland, Montana,

to pursue a master’s degree at the university in Missoula. On the evening I

left, with late-August shadows creeping across the road in front of Maurice’s

house in The Village, the setting sun shone into eyes that revealed nothing

to me. I thought I would never see him again.

While in Missoula, I began journaling about my four years as a high

school English teacher on the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation. Most

entries evolved into accounts of Maurice. I guess I hoped my friendship

had changed his life, and I searched for evidence of this in my stories, or I

sought at least to prove there was meaning to what otherwise were years

of my life that seemed directionless and wasted.

As life tends to drag us to places we don’t foresee, it can also put us back

in places we thought we were done with. I returned to Ashland a year later.

I had met a woman in Missoula, married her over the summer, and brought

her back with me to the reservation. But Maurice didn’t seem to like her

and began avoiding me. He also started skipping school. I realized then

that I could not save him, and I dreaded the end of his story, or I realized

there’d be no end and I was only reaching into his life clumsily without

really touching it. I couldn’t decide which was worse. Of course, I was

wrong. There was an end. And it was even worse. Although no one at the

time seemed to know the details to explain what had happened.

The article was as brief as his life, consisting of just seventy-one words

written in three fleeting paragraphs, answering the who, what, when, where,

and how. It opened with “Two people died when their car pulled around

a crossing arm and was hit by a train.” This sentence contained information

I hadn’t heard. I was told his car was hit by a train but not as it pulled

around a crossing arm.

I learned more. Maurice was not the driver. I didn’t recognize the other

name (so I left that person out of this story). Maurice’s two-word last name

must have confused the reporter, who shortened Prairie to P and treated

it like a middle initial: “Maurice P. Chief, of Risco,” which was strange to

read, given that he had lived all but a few months of his life in Ashland,

Montana. Maurice was not from Risco, not from Missouri.

For some reason, I found comfort in learning that Maurice wasn’t behind

the wheel. Not that he wouldn’t have tried to get around a crossing arm—he

was reckless and daring, always with a smile on his face when speed and

danger were involved—but I had let him drive my Ford Ranger xlt in the

forests around Ashland when he was ten. I knew he had skills.

No, I’m convinced Maurice would have made it through.

Both victims were pronounced dead at the scene of the accident. Maurice

died shortly before midnight on Saturday, March 13, 1999, one year to the

day before my daughter, Sarah, was born. He was seventeen.

The last line read, “No one was injured aboard the southbound Union

Pacific freight train.”

What was missing were the whys.

Cuprins

List of Illustrations

Foreword by He’seota’e Miner

Acknowledgments

1. As Brief as His Life

2. What I Knew

3. Cool, Indian Kids!

4. Teacher Dave from Minnesota

5. Fishing at Sitting Man Dam

6. Needed: High School English Teacher

7. Sleep, without Restless Dreams

8. I’ve Never Been Good at Algebra

9. Chimney Rock

10. Labor Day Powwow

11. Eagleman and Hawkman

12. Peyote Meeting at the Medicine Bull’s

13. The Search for Fisher’s Butte

14. New Possibilities That Felt like Gifts

15. Sweat Hobo

16. Stag Rock and Birthdays at the Runs Above’s

17. Get Studly to Run

18. It Makes Me Think of Uncle Doug

19. The Huckleberry Party and Others

20. The Balance of This Day

21. Pissing the Day Away

22. Hawkman Tries to Say Goodbye to Eagleman

23. What Elaine Littlebird Said

24. Time and Distance

25. You Don’t Wanna Help Me, Then, Do You?

26. Shooting Star

27. I Should Have Known More

28. Swallowed by the Darkness

29. He Knows How to Ride

30. I Wanted Him to Stay

31. All the Words I Was Forming, I Held Onto

32. Wrong about Buffalo One More Time

Foreword by He’seota’e Miner

Acknowledgments

1. As Brief as His Life

2. What I Knew

3. Cool, Indian Kids!

4. Teacher Dave from Minnesota

5. Fishing at Sitting Man Dam

6. Needed: High School English Teacher

7. Sleep, without Restless Dreams

8. I’ve Never Been Good at Algebra

9. Chimney Rock

10. Labor Day Powwow

11. Eagleman and Hawkman

12. Peyote Meeting at the Medicine Bull’s

13. The Search for Fisher’s Butte

14. New Possibilities That Felt like Gifts

15. Sweat Hobo

16. Stag Rock and Birthdays at the Runs Above’s

17. Get Studly to Run

18. It Makes Me Think of Uncle Doug

19. The Huckleberry Party and Others

20. The Balance of This Day

21. Pissing the Day Away

22. Hawkman Tries to Say Goodbye to Eagleman

23. What Elaine Littlebird Said

24. Time and Distance

25. You Don’t Wanna Help Me, Then, Do You?

26. Shooting Star

27. I Should Have Known More

28. Swallowed by the Darkness

29. He Knows How to Ride

30. I Wanted Him to Stay

31. All the Words I Was Forming, I Held Onto

32. Wrong about Buffalo One More Time

Recenzii

"Crafting a readable memoir is no mean feat in perhaps the most oversaturated genre in publishing. But Charpentier succeeds in conveying a deeply personal histoire through elegant prose that is simple and heartfelt."—Montana The Magazine of Western History

"The Boy Who Promised Me Horses is a testament to the power of friendship and the ability of a chance encounter to change a life forever."—Big Sky Journal

“Beautifully embodied by the people who inhabit the Northern Cheyenne community in southeast Montana, this journey is fraught with difference, ambiguity, and harm, historical and present, taking us into the shadows of our individual and national interiority and helping us acknowledge not only shadow but light.”—Shann Ray, American Book Award winner and author of The Souls of Others

“A beautiful tale of friendship, memory, and loss. Charpentier didn’t go to the Northern Cheyenne Reservation or make friends with Maurice Prairie Chief in order to write a book. He wrote the book because he had a story he needed to tell. The result is a look at reservation life that is achingly honest, both about the people he came to know and about himself.”—Ed Kemmick, author of The Big Sky, By and By: True Tales, Real People, and Strange Times in the Heart of Montana

“The most powerful and heartfelt stories are the stories we don’t see coming, about the people who live quietly at the edge of our lives and offer untold love and meaning. The Boy Who Promised Me Horses is a love story lit from within. Unexpected, powerful, and deeply moving.”—Debra Magpie Earling, author of The Lost Journals of Sacajewea

“The Boy Who Promised Me Horses is not only a lyrical account of the narrator’s friendship with Maurice Prairie Chief, it is a haunting tragedy, a cross-cultural narrative that explores the mystery of friendship and the impossibility of ever really knowing another person. Dave Charpentier has crafted an indelible and unforgettable story.”—Tami Haaland, author of What Does Not Return

“David Charpentier’s The Boy Who Promised Me Horses is humble, wise, honest, full of wonder, and absolutely, devastatingly heartbreaking. Which is as it should be. The story of the American West is one of genocide, thievery, and forced assimilation—and that’s the historical legacy David Charpentier meets head-on as a young English teacher at a high school on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in southeastern Montana. Yet, too, in his time on the reservation Mr. Sharp begins to learn resilience and loyalty and a deep and sustaining culture. And most of all, he learns friendship. You’ll be thinking about Charpentier and Maurice Prairie Chief long after you turn the last page.”—Joe Wilkins, author of Fall Back Down When I Die

Descriere

A teacher and mentor to students at St. Labre Indian School, David Joseph Charpentier details the joys, dangers, and complexities of life on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in this thoughtful tribute to one of his more memorable students, Maurice Prairie Chief.