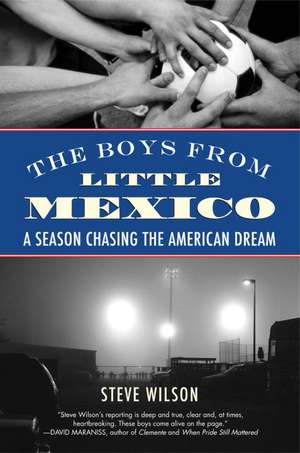

The Boys from Little Mexico: A Season Chasing the American Dream

Autor Steve Wilsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2011

More than just riveting sports writing, The Boys from Little Mexico is about the fight for the future of the next generation—and a hard, true look at boys dismissed as gang-bangers, told to “go home” by lily-white sideline crowds. The wins and losses they notch along the way spin a striking tale about what it takes to capture the American Dream.

Preț: 148.76 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 223

Preț estimativ în valută:

28.47€ • 29.61$ • 23.50£

28.47€ • 29.61$ • 23.50£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 14-28 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780807001523

ISBN-10: 080700152X

Pagini: 225

Dimensiuni: 152 x 226 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: Beacon Press (MA)

ISBN-10: 080700152X

Pagini: 225

Dimensiuni: 152 x 226 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: Beacon Press (MA)

Notă biografică

Steve Wilson is the former publisher and editor of Motionsickness: The Other Side of Travel, a critically lauded magazine that was selected as a finalist for Utne's Best New Titles for 2001. He has also been published widely in newspapers and magazines, including the Portland Tribune, American History, and Utne. A graduate of Portland State University's MA Writing Program, he teaches at PSU.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

In The Boys from Little Mexico, Steve Wilson does more than chase the American Dream—he captures it on the move. Wilson provides us with a glimpse of the future of sports in America, one that promises to be as rich and compelling as the past.—Glenn Stout, author and Series Editor of The Best American Sports Writing

"I hate soccer … but I loved this book. Steve Wilson has written a story where culture, sport, and good writing collide."—Larry Colton, former pitcher for the Philadelphia Phillies and author of Counting Coup

"Just as Buzz Bissinger did in Friday Night Lights, Steve Wilson manages to achieve the unexpected: a book about sports that turns out to be about so much more. He wrests poetry out of these boys' lives, while aiming directly for that one destination where we all seek home—the heart."—Luis Alberto Urrea, author of Into the Beautiful North and The Devil's Highway

"With compassion and an unflinching eye, Steve Wilson offers us through sports a preview of a new America, one whose people may look different, but whose virtues of what we like to believe in ourselves remain triumphantly the same.—Howard Bryant, ESPN senior writer and author of The Last Hero

"A real-life account of the inequities surrounding immigration as lived by all concerned, this year in the life of the Woodburn Bulldogs offers no easy answers. The frustrations they face are saddening, but theirs is ultimately a hopeful tale. Very timely, with the World Cup in 2010!"—Dana Brigham, manager/co-owner, Brookline (Mass.) Booksmith

"The Boys from Little Mexico proves once again that the language of sports is universal. Steve Wilson takes a small corner of the world and shows how big it can be, especially when a caring coach partners with some talented players. This book is both heartbreaking and inspiring."—Madeleine Blais, author of In These Girls, Hope Is a Muscle

"The Boys from Little Mexico is an unvarnished and moving account of the dreams and despair of immigrant boys on a high school soccer team who struggle not only in their quest to win the state championship, but also in their desire to adapt as strangers in a new land. If you want to understand your new next-door neighbors, this is the book to read.—Sonia Nazario, author of Enrique's Journey

"On one level Steve Wilson has written a wonderful book about high school athletes in a community banded together by soccer glory. On another level, he's written a wonderful book about race, sociology, and the shifting borders within this country. The Boys from Little Mexico will tell you more about the next generation of Americans than census data and politicians ever could."—Bill Reynolds, author of Fall River Dreams and ’78

"American soccer is far too often viewed as a country club sport. Steve Wilson spent five years earning the trust of Los Perros in order to put a human face on the young men of America's fastest-growing minority group. With empathy and respect, Wilson reveals their compelling stories."—Grant Wahl, senior writer for Sports Illustrated and author of The Beckham Experiment

"Steve Wilson's reporting is deep and true, clear and, at times, heartbreaking. These boys come alive on the page."—David Maraniss, author of Clemente and When Pride Still Mattered

From the Hardcover edition.

"I hate soccer … but I loved this book. Steve Wilson has written a story where culture, sport, and good writing collide."—Larry Colton, former pitcher for the Philadelphia Phillies and author of Counting Coup

"Just as Buzz Bissinger did in Friday Night Lights, Steve Wilson manages to achieve the unexpected: a book about sports that turns out to be about so much more. He wrests poetry out of these boys' lives, while aiming directly for that one destination where we all seek home—the heart."—Luis Alberto Urrea, author of Into the Beautiful North and The Devil's Highway

"With compassion and an unflinching eye, Steve Wilson offers us through sports a preview of a new America, one whose people may look different, but whose virtues of what we like to believe in ourselves remain triumphantly the same.—Howard Bryant, ESPN senior writer and author of The Last Hero

"A real-life account of the inequities surrounding immigration as lived by all concerned, this year in the life of the Woodburn Bulldogs offers no easy answers. The frustrations they face are saddening, but theirs is ultimately a hopeful tale. Very timely, with the World Cup in 2010!"—Dana Brigham, manager/co-owner, Brookline (Mass.) Booksmith

"The Boys from Little Mexico proves once again that the language of sports is universal. Steve Wilson takes a small corner of the world and shows how big it can be, especially when a caring coach partners with some talented players. This book is both heartbreaking and inspiring."—Madeleine Blais, author of In These Girls, Hope Is a Muscle

"The Boys from Little Mexico is an unvarnished and moving account of the dreams and despair of immigrant boys on a high school soccer team who struggle not only in their quest to win the state championship, but also in their desire to adapt as strangers in a new land. If you want to understand your new next-door neighbors, this is the book to read.—Sonia Nazario, author of Enrique's Journey

"On one level Steve Wilson has written a wonderful book about high school athletes in a community banded together by soccer glory. On another level, he's written a wonderful book about race, sociology, and the shifting borders within this country. The Boys from Little Mexico will tell you more about the next generation of Americans than census data and politicians ever could."—Bill Reynolds, author of Fall River Dreams and ’78

"American soccer is far too often viewed as a country club sport. Steve Wilson spent five years earning the trust of Los Perros in order to put a human face on the young men of America's fastest-growing minority group. With empathy and respect, Wilson reveals their compelling stories."—Grant Wahl, senior writer for Sports Illustrated and author of The Beckham Experiment

"Steve Wilson's reporting is deep and true, clear and, at times, heartbreaking. These boys come alive on the page."—David Maraniss, author of Clemente and When Pride Still Mattered

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

I carried my one-year-old son, Ben, across the springy running track

—one of those made from recycled athletic shoes—heading toward

a grass field where about two dozen boys ran back and forth, their

attention focused on a black-and-white ball. Coach Mike Flannigan

stood watching them, a tall pacing figure, face shaded by a dark baseball

cap. He nodded at me as I put Ben down and turned his attention

back to the game. The sun, blindingly bright, gleamed off a row of

metal bleachers nearby.

For the next fifteen minutes, I alternately chased my son and

watched the game. Even with my attention distracted, it didn’t take

long to notice a wiry midfielder with a pencil-thin mustache who

had tremendous ball control. The ball left his foot, bounced around

among the other players, and returned, almost as if it were on a string.

Like the others that Mike coached, this kid was Hispanic; unlike the

others, he played with focus and intensity, his face stern, almost grim.

His teammates seemed to be enjoying themselves, but Mustache was

locked in a fight.

I picked up Ben and walked over to Coach Flannigan as Mustache

trapped a pass and dribbled around an opposing player.

“Who’s that?” I asked.

“Oh, you noticed,” Mike said. “That’s Octavio. He’s probably our

best player.”

He was clearly the best player in the group, moving around like a

spider, the soccer field his web.

“Where’s he from?”

Coach Flannigan glanced over. “You’ll have to ask him,” he said.

People from Woodburn can be reluctant to discuss their birthplace.

With few exceptions, Latinos in Woodburn either were born

in Mexico or are Mexican-descended Americans, and for those

born in Mexico, legal status can be a touchy subject.

Sweat trickled down my forehead, and Ben struggled in my arms

as something caught his attention. I put him down.

“Have you met Carlos?” Coach Flannigan asked. He gestured

toward a nearby bench, where a well-built teen sat talking to a girl

about his own age. Carlos turned and looked at us. His black hair

was combed forward over his forehead and seemed to shimmer with

either water or styling product.

“Hi,” he said.

“How come you’re not playing?” I asked.

“Injured,” he said, gesturing toward a leg.

“Carlos is our keeper,” Coach Flannigan said, his eyes still on the

game. “He’s probably the best keeper in the state.”

Carlos snorted and turned back to the girl.

“These two guys are going to be the key to our next season,” the

coach said. “Hopefully, they can both keep healthy.”

More sweat trickled down, and I removed my sunglasses to wipe

my face. It was ninety-two degrees, the middle of August, and the

temperature was forecast to approach one hundred—unusually hot

for northern Oregon. The kids on the field were only a skeleton crew

of the entire Woodburn High School squad, but here they were,

playing an intense pickup game against another partial team at midday

on a shadeless field while their coach stood watching, unpaid

because it was summer.

Ben tottered off toward some football equipment and I followed,

thinking, these guys sure take their soccer seriously.

I first heard of the Woodburn Bulldogs soccer team when I came

across a newspaper article about a game between the Bulldogs and

the visiting Lakeridge Pacers, from Lake Oswego, a town twenty

miles north of Woodburn. I lost the article after I read it and never

tracked it down again, but I recall the story, in a Lake Oswego paper,

describing the Pacers traveling to a hostile and foreign land where

Spanish was more common than English, and where, the article

seemed to suggest, the visiting team was lucky to leave with their

cars’ windshields intact.

Lakeridge is one of two high schools in the town of Lake Oswego,

the most upper-crust suburb of Portland, Oregon’s largest city.

It’s a town where the wealthy live, which means almost everyone is

white. Locals joke about Lake Oswego’s lack of diversity by calling it

“Lake No-Negro.”

Woodburn, on the other hand, calls itself “The City of Unity”

and may be Oregon’s most ethnically diverse community. As of the

2000 census, Woodburn was 51 percent Hispanic, 49 percent Anglo.

Even this is somewhat misleading, since about 30 percent of

Woodburn’s “Anglo” population belongs to a non-Latino group

of immigrants, Russian Old Believers, large, sunburned men with

long beards and women with scarf-covered heads, about ten thousand

of whom fled religious persecution and ended up around Woodburn

in the 1950s and 1960s.

The Woodburn Bulldogs and the Lakeridge Pacers don’t play

each other often. Because the teams are from different regional

leagues, the only times they meet are in pre- and postseason matches.

Both schools typically field very good soccer teams; beyond that,

there are few resemblances. The two schools represent two completely

different Oregons. One could say that they represent two

completely different Americas.

Lake Oswego’s population is about 90 percent white, and an average

resident makes $75,000 a year. Lake Oswego’s most notable

feature is a privately owned lake surrounded by expensive homes.

Woodburn, a short drive to the south, has a median income half that

of Lake Oswego’s. The most notable feature in Woodburn? The Mac-

Laren Youth Correctional Facility.

The differences extend to the high schools. The students who

attend Lakeridge, considered one of the best public high schools

in the state, go to college: about 80 percent of Lakeridge grads attend

a four-year university and 10 percent attend a community college.

Only 5 percent of Lakeridge students are eligible for a free or

reduced-price lunch. At Woodburn High, 75 percent of the students

are eligible for a free or reduced-price lunch. Not long ago, a lower

percentage of Woodburn students graduated high school than Lakeridge

sent to universities. It’s so rare that Woodburn’s Hispanic students

receive scholarships that the local newspaper writes profiles

about the kids who do.

With all this in mind, it’s not surprising that people from the two

communities don’t mix—usually when they do, it’s because one is

mowing the other’s lawn. The one place the two communities come

together on equal footing is on the soccer field. Not coincidentally,

the two demographic groups represented on that field—uppermiddle-

class Anglos and working-class Hispanics—are also the two

groups in the United States for whom soccer is a real sport and not

a punch line.

At the time I first read about Woodburn’s soccer team, I was still

a new arrival in Oregon. Woodburn, I knew, had factory outlets—I

had seen them from the freeway—but I lumped in Woodburn with

dozens of other single-exit suburbs cluttering the hour-long drive

between Portland and Salem, the state capital. I didn’t know that at

the town’s Greyhound station, one could buy a one-way ticket to the

Nayarit city of Tepic, or that downtown Woodburn had the highest

concentration of taquerias in the state, or that for girls in Woodburn,

turning fifteen was a really big deal. Visiting one weekend, I found

that the single exit became a two-lane highway curving into Woodburn,

with more traffic than the town deserved. Highway 214 was

choked with trucks carrying agricultural supplies to or from the area’s

farms and nurseries. A distant line of green hills squatted beyond the

town.

The residential neighborhoods looked like . . . well, pretty much

every other small town in the Northwest: a combination of new and

old architecture, lots of trees, pickup trucks, minivans, and a scattering

of churches. But, one thing was different. In parks and vacant lots,

in front yards and in driveways, I saw boys and men kicking around

la pelota—the soccer ball. In Woodburn, on Saturday afternoons, the

town’s parks are crowded with Hispanic men’s league games, and the

high point of the town’s biggest annual celebration, August’s Fiesta

Mexicana, is an intense men’s league tournament. The men I grew

up with spent Saturdays playing golf or tennis; in Woodburn, men

play fútbol.

—one of those made from recycled athletic shoes—heading toward

a grass field where about two dozen boys ran back and forth, their

attention focused on a black-and-white ball. Coach Mike Flannigan

stood watching them, a tall pacing figure, face shaded by a dark baseball

cap. He nodded at me as I put Ben down and turned his attention

back to the game. The sun, blindingly bright, gleamed off a row of

metal bleachers nearby.

For the next fifteen minutes, I alternately chased my son and

watched the game. Even with my attention distracted, it didn’t take

long to notice a wiry midfielder with a pencil-thin mustache who

had tremendous ball control. The ball left his foot, bounced around

among the other players, and returned, almost as if it were on a string.

Like the others that Mike coached, this kid was Hispanic; unlike the

others, he played with focus and intensity, his face stern, almost grim.

His teammates seemed to be enjoying themselves, but Mustache was

locked in a fight.

I picked up Ben and walked over to Coach Flannigan as Mustache

trapped a pass and dribbled around an opposing player.

“Who’s that?” I asked.

“Oh, you noticed,” Mike said. “That’s Octavio. He’s probably our

best player.”

He was clearly the best player in the group, moving around like a

spider, the soccer field his web.

“Where’s he from?”

Coach Flannigan glanced over. “You’ll have to ask him,” he said.

People from Woodburn can be reluctant to discuss their birthplace.

With few exceptions, Latinos in Woodburn either were born

in Mexico or are Mexican-descended Americans, and for those

born in Mexico, legal status can be a touchy subject.

Sweat trickled down my forehead, and Ben struggled in my arms

as something caught his attention. I put him down.

“Have you met Carlos?” Coach Flannigan asked. He gestured

toward a nearby bench, where a well-built teen sat talking to a girl

about his own age. Carlos turned and looked at us. His black hair

was combed forward over his forehead and seemed to shimmer with

either water or styling product.

“Hi,” he said.

“How come you’re not playing?” I asked.

“Injured,” he said, gesturing toward a leg.

“Carlos is our keeper,” Coach Flannigan said, his eyes still on the

game. “He’s probably the best keeper in the state.”

Carlos snorted and turned back to the girl.

“These two guys are going to be the key to our next season,” the

coach said. “Hopefully, they can both keep healthy.”

More sweat trickled down, and I removed my sunglasses to wipe

my face. It was ninety-two degrees, the middle of August, and the

temperature was forecast to approach one hundred—unusually hot

for northern Oregon. The kids on the field were only a skeleton crew

of the entire Woodburn High School squad, but here they were,

playing an intense pickup game against another partial team at midday

on a shadeless field while their coach stood watching, unpaid

because it was summer.

Ben tottered off toward some football equipment and I followed,

thinking, these guys sure take their soccer seriously.

I first heard of the Woodburn Bulldogs soccer team when I came

across a newspaper article about a game between the Bulldogs and

the visiting Lakeridge Pacers, from Lake Oswego, a town twenty

miles north of Woodburn. I lost the article after I read it and never

tracked it down again, but I recall the story, in a Lake Oswego paper,

describing the Pacers traveling to a hostile and foreign land where

Spanish was more common than English, and where, the article

seemed to suggest, the visiting team was lucky to leave with their

cars’ windshields intact.

Lakeridge is one of two high schools in the town of Lake Oswego,

the most upper-crust suburb of Portland, Oregon’s largest city.

It’s a town where the wealthy live, which means almost everyone is

white. Locals joke about Lake Oswego’s lack of diversity by calling it

“Lake No-Negro.”

Woodburn, on the other hand, calls itself “The City of Unity”

and may be Oregon’s most ethnically diverse community. As of the

2000 census, Woodburn was 51 percent Hispanic, 49 percent Anglo.

Even this is somewhat misleading, since about 30 percent of

Woodburn’s “Anglo” population belongs to a non-Latino group

of immigrants, Russian Old Believers, large, sunburned men with

long beards and women with scarf-covered heads, about ten thousand

of whom fled religious persecution and ended up around Woodburn

in the 1950s and 1960s.

The Woodburn Bulldogs and the Lakeridge Pacers don’t play

each other often. Because the teams are from different regional

leagues, the only times they meet are in pre- and postseason matches.

Both schools typically field very good soccer teams; beyond that,

there are few resemblances. The two schools represent two completely

different Oregons. One could say that they represent two

completely different Americas.

Lake Oswego’s population is about 90 percent white, and an average

resident makes $75,000 a year. Lake Oswego’s most notable

feature is a privately owned lake surrounded by expensive homes.

Woodburn, a short drive to the south, has a median income half that

of Lake Oswego’s. The most notable feature in Woodburn? The Mac-

Laren Youth Correctional Facility.

The differences extend to the high schools. The students who

attend Lakeridge, considered one of the best public high schools

in the state, go to college: about 80 percent of Lakeridge grads attend

a four-year university and 10 percent attend a community college.

Only 5 percent of Lakeridge students are eligible for a free or

reduced-price lunch. At Woodburn High, 75 percent of the students

are eligible for a free or reduced-price lunch. Not long ago, a lower

percentage of Woodburn students graduated high school than Lakeridge

sent to universities. It’s so rare that Woodburn’s Hispanic students

receive scholarships that the local newspaper writes profiles

about the kids who do.

With all this in mind, it’s not surprising that people from the two

communities don’t mix—usually when they do, it’s because one is

mowing the other’s lawn. The one place the two communities come

together on equal footing is on the soccer field. Not coincidentally,

the two demographic groups represented on that field—uppermiddle-

class Anglos and working-class Hispanics—are also the two

groups in the United States for whom soccer is a real sport and not

a punch line.

At the time I first read about Woodburn’s soccer team, I was still

a new arrival in Oregon. Woodburn, I knew, had factory outlets—I

had seen them from the freeway—but I lumped in Woodburn with

dozens of other single-exit suburbs cluttering the hour-long drive

between Portland and Salem, the state capital. I didn’t know that at

the town’s Greyhound station, one could buy a one-way ticket to the

Nayarit city of Tepic, or that downtown Woodburn had the highest

concentration of taquerias in the state, or that for girls in Woodburn,

turning fifteen was a really big deal. Visiting one weekend, I found

that the single exit became a two-lane highway curving into Woodburn,

with more traffic than the town deserved. Highway 214 was

choked with trucks carrying agricultural supplies to or from the area’s

farms and nurseries. A distant line of green hills squatted beyond the

town.

The residential neighborhoods looked like . . . well, pretty much

every other small town in the Northwest: a combination of new and

old architecture, lots of trees, pickup trucks, minivans, and a scattering

of churches. But, one thing was different. In parks and vacant lots,

in front yards and in driveways, I saw boys and men kicking around

la pelota—the soccer ball. In Woodburn, on Saturday afternoons, the

town’s parks are crowded with Hispanic men’s league games, and the

high point of the town’s biggest annual celebration, August’s Fiesta

Mexicana, is an intense men’s league tournament. The men I grew

up with spent Saturdays playing golf or tennis; in Woodburn, men

play fútbol.

Cuprins

Preface

Introduction

The Field of Play

Preseason

One: Steps to Success

Two: The Immigrants’ Game

Three: Octavio

Four: Water on Stone

Season

Five: A Lush and Level Field

Six: El Norte

Seven: Carlos

Eight: Adjustments

Nine: The Woodburn Curse

Ten: Reading and Writing

Eleven: Playing Rough

Postseason

Twelve: The Fourth Seed

Thirteen: This Dream

Fourteen: Just a Game

Fifteen: Game Over

Epilogue

Introduction

The Field of Play

Preseason

One: Steps to Success

Two: The Immigrants’ Game

Three: Octavio

Four: Water on Stone

Season

Five: A Lush and Level Field

Six: El Norte

Seven: Carlos

Eight: Adjustments

Nine: The Woodburn Curse

Ten: Reading and Writing

Eleven: Playing Rough

Postseason

Twelve: The Fourth Seed

Thirteen: This Dream

Fourteen: Just a Game

Fifteen: Game Over

Epilogue