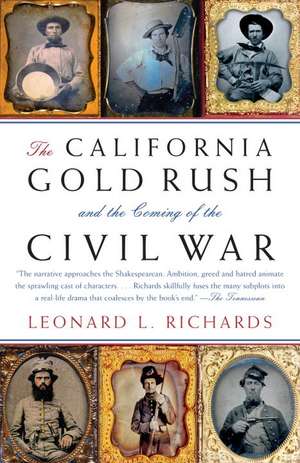

The California Gold Rush and the Coming of the Civil War: Vintage Civil War Library

Autor Leonard L. Richardsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2008

When gold was discovered at Sutter's Mill in 1848, Americans of all stripes saw the potential for both wealth and power. Among the more calculating were Southern slave owners. By making California a slave state, they could increase the value of their slaves—by 50 percent at least, and maybe much more. They could also gain additional influence in Congress and expand Southern economic clout, abetted by a new transcontinental railroad that would run through the South. Yet, despite their machinations, California entered the union as a free state. Disillusioned Southerners would agitate for even more slave territory, leading to the Kansas-Nebraska Act and, ultimately, to the Civil War itself.

Din seria Vintage Civil War Library

-

Preț: 102.62 lei

Preț: 102.62 lei -

Preț: 107.63 lei

Preț: 107.63 lei -

Preț: 121.68 lei

Preț: 121.68 lei -

Preț: 144.52 lei

Preț: 144.52 lei -

Preț: 139.90 lei

Preț: 139.90 lei -

Preț: 136.71 lei

Preț: 136.71 lei -

Preț: 136.30 lei

Preț: 136.30 lei -

Preț: 100.24 lei

Preț: 100.24 lei -

Preț: 125.54 lei

Preț: 125.54 lei -

Preț: 134.74 lei

Preț: 134.74 lei -

Preț: 122.76 lei

Preț: 122.76 lei -

Preț: 99.36 lei

Preț: 99.36 lei -

Preț: 143.78 lei

Preț: 143.78 lei -

Preț: 133.47 lei

Preț: 133.47 lei -

Preț: 100.42 lei

Preț: 100.42 lei -

Preț: 149.08 lei

Preț: 149.08 lei -

Preț: 116.64 lei

Preț: 116.64 lei -

Preț: 144.04 lei

Preț: 144.04 lei -

Preț: 196.43 lei

Preț: 196.43 lei -

Preț: 115.32 lei

Preț: 115.32 lei -

Preț: 117.18 lei

Preț: 117.18 lei -

Preț: 105.40 lei

Preț: 105.40 lei -

Preț: 198.45 lei

Preț: 198.45 lei -

Preț: 117.10 lei

Preț: 117.10 lei -

Preț: 99.14 lei

Preț: 99.14 lei -

Preț: 98.11 lei

Preț: 98.11 lei -

Preț: 110.75 lei

Preț: 110.75 lei - 18%

Preț: 71.23 lei

Preț: 71.23 lei - 16%

Preț: 80.42 lei

Preț: 80.42 lei -

Preț: 102.90 lei

Preț: 102.90 lei -

Preț: 102.69 lei

Preț: 102.69 lei

Preț: 109.32 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 164

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.92€ • 21.76$ • 17.27£

20.92€ • 21.76$ • 17.27£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307277572

ISBN-10: 0307277577

Pagini: 289

Ilustrații: 42 ILLUS & 8 MAPS

Dimensiuni: 149 x 204 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Seria Vintage Civil War Library

ISBN-10: 0307277577

Pagini: 289

Ilustrații: 42 ILLUS & 8 MAPS

Dimensiuni: 149 x 204 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Seria Vintage Civil War Library

Notă biografică

Leonard L. Richards, Professor of History at the University of Massachusetts, grew up in California, and earned his AB, MA, and Ph.D. at the University of California, Berkeley and Davis. He has also taught at San Francisco State College and the University of Hawaii. His "Gentlemen of Property and Standing": Anti-Abolition Mobs in Jacksonian America won the American Historical Association's Albert J. Beveridge Award in 1970. The Life and Times of Congressman John Quincy Adams was a Finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 1987 and The Slave Power: The Free North and Southern Domination, 1780-1860 took the second-place Lincoln Prize in 2001. He is also the author, with William Graebner, of The American Record (1981, 1987, 1995, 2000, 2005) and of Shay's Rebellion: The American Revolution's Final Battle (2002). He and his wife live in Amherst, Massachusetts.

Extras

Chapter 1

The chain of events that led to the killing began in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada on a cold morning in late January 1848. That morning, as every morning for the past several months, Jennie Wimmer had been working over a hot woodstove. Her task at the moment was making soap. Technically, she was the cook and laundress for a crew of white men, mainly Mormons, who were building a sawmill on the south fork of the American River. In fact, however, she had so alienated the Mormons that they no longer ate at her table.

Initially the men had welcomed her. Tired of their own cooking and eager to have a woman in the kitchen, they had even accepted the fact that she always served the choice portions of pork and mutton to her husband, Peter, and her seven children. But she had treated them shabbily and worn out her welcome. Whenever she rang the dinner bell, she had expected them to appear at once, and on Christmas morning, when they had taken extra time washing up, she had bawled them out, telling them that “she was Boss” and that they “must come at the first call” or go without breakfast. With that, they had “revolted from under her government” and decided to build their own separate cabin and cook for themselves.

What had made matters worse was that Jennie Wimmer wasn’t an old tyrant. She was a young one, just twenty-six years old, much younger than some of the men. She also cursed, and, like most white women in California at this time, she had been around.

Christened Elizabeth Jane, but always called Jennie, she was the daughter of a Virginia tobacco farmer who in 1838 had moved his family to Lumpkin County, Georgia, to mine gold. There she and her mother had run a boardinghouse for local miners, and there she had met a young miner named Obadiah Baiz. They had married and moved to Missouri in 1840. He had died in 1843, leaving her a widow with two children. She then married Peter Wimmer, a thirty-three-year-old widower from Cincinnati with five children. In the spring of 1846 the Wimmers decided to leave the United States and head west to Mexican California. They joined a wagon train of eighty-four migrants, trekked across the Rockies and Sierras, and arrived at Sutter’s Fort, in what is now Sacramento, on November 15, 1846.

The following spring the owner of the fort, Johann Sutter, decided to build a sawmill for his rapidly expanding agricultural empire. He, too, had been around. He had fled Switzerland for New York in 1834, leaving behind a wife and four children, large debts, and a warrant for his arrest. He then went to Missouri, New Mexico, Oregon, Hawaii, and Alaska before he reached California in 1839. Since then he had become a Mexican citizen and persuaded the governor of California to grant him a huge tract of land in the Sacramento valley, which he had dubbed New Helvetia. He was now forty-four years old and saw nothing but glory days lying ahead.

The site Sutter picked for his sawmill was some forty miles from his home base, on the south fork of the American River, in a place that came to be known as Coloma. Had Sutter been in his native Switzerland, he could have found plenty of millwrights who knew how to tap the power of falling water. But in the Sacramento valley finding a skilled millwright or even a millwright’s apprentice was next to impossible. So to oversee the operation Sutter turned to James Marshall, a thirty-seven-year-old New Jersey carpenter who had tried his hand at ranching in the Sacramento valley and failed miserably.

Sutter assigned thirteen of his Mormon hands to work under Marshall. They were part of a larger contingent of eight hundred Mormons who had been sent by Salt Lake City to earn money fighting in the Mexican War. This contingent in 1847 had come to Sutter’s Fort on their way back to Utah. About eighty had stayed to work, not for wages, but for horses and cattle to take home with them. Sutter still had nearly fifty Mormon hands. He thought that they were the best workers he had ever encountered. The men he assigned to Marshall had agreed to stay until the following spring. Then they planned to head east across the mountains to join Brigham Young and their fellow Saints on the shores of the Great Salt Lake. They, too, had been around. One of their leaders, Henry Bigler, had survived the anti-Mormon wars in Missouri and Illinois and now was an elder in the Mormon church.

Sutter also employed Maidu Indians. He essentially rented them from tribal leaders. He had for years, using some as personal servants, others to dig irrigation ditches and plant his orchards. He didn’t think much of their work habits, but they cost him much less than the Mormons, and so he decided to have one Maidu crew dig the race for his sawmill. To oversee them he hired Jennie Wimmer’s husband, Peter. The camp also needed a cook and a laundress, and for those duties Sutter hired Jennie, not knowing that her dictatorial ways would drive Henry Bigler and his fellow Mormons to the point of rebellion.

As luck would have it, however, Jennie Wimmer had one skill that the others lacked. Thanks to her time in Georgia, she knew how to tell the difference between gold and fool’s gold. That knowledge proved helpful when Peter brought to her kitchen a pebble that James Marshall had found earlier that morning in the freshly dug tail race. The find had excited Marshall, so much so that he ran back to his Mormon crew, shouting: “Boys, by God I believe I have found a gold mine!”

The workers, however, had been skeptical. They had tested the metal, biting and hammering it to see if it was brittle, and found that it was malleable. But they still had doubts. So, too, did Marshall. The chips he found just didn’t have enough luster, he thought, to be gold. Didn’t gold glisten? He wasn’t certain. Nor was Peter. But Jennie knew what to do with the pebble Peter handed her. She tossed it into a kettle of soap she was making, knowing that it would corrode if it was fool’s gold. She then finished making the soap and set it off to cool. The next morning one of the hands asked her about the pebble. “I told him it was in my soap kettle. . . . A plank was brought for me to lay my soap onto, and I cut it in chunks, but it was not to be found. At the bottom of the pot was a double handful of potash, which I lifted in my two hands, and there was my gold as bright as could be.”

James Marshall then braved a drenching rain to take the news to Sutter. He found Sutter writing at his office desk, totally surprised to see him. Hadn’t Marshall just received all the supplies he needed? To Sutter’s further surprise, Marshall then insisted that the door be locked and asked for two pails of water and a scale. He then showed Sutter what he had found, and the two men spent the next couple of hours consulting the American Encyclopedia and doing one experiment after another. They bit and hammered the metal to see if it was malleable. They doused it with nitric acid to see if it would tarnish. They weighed it against silver. They weighed it a second time—and then a third. They immersed the scales into a pail of water to see if it had greater specific gravity and sunk to the bottom. Finally, after again consulting the American Encyclopedia, they pronounced it gold.

Sutter decided that the discovery must be kept secret. The next day he rode up to Coloma. “I had a talk with my employed people all at the Sawmill” and asked “that they would do me the great favor and keep it a secret.” But he forgot to silence Jennie Wimmer and her sons. They told all who came by, including a teamster, Jacob Wittner, who carried the news back to Sutter’s Fort. Sutter himself also had loose lips, and by March the news had reached San Francisco.

The first reports were dismissed as nonsense. Legends, talk, and boasts of gold had been heard many times before. Just six years earlier, in 1842, gold had been found in the mountains just north of Los Angeles, but the find played out quickly. Maybe Coloma would just be more of the same. The two weekly San Francisco newspapers, The Californian and The California Star, treated the first reports with casual indifference.

In downplaying the reports, the Star’s owner had an ulterior motive. The newspaper belonged to Sam Brannan, a dapper and friendly man who seemingly spent half his time serving God, the other half serving mammon. A twenty-nine-year-old Maine native, Brannan had been a Mormon leader for most of his adult life. When he was fourteen years old, his sister had married a Mormon missionary, and he tagged along with the honeymoon couple to what was then the Mormon headquarters in Kirtland, Ohio. He had converted to the faith, helped build the first temple, and become a printer. He was then sent to New York City as the East Coast publisher of Mormon literature. He made valuable commercial contacts there and by age twenty-five had become a rich man.

Then, in 1844, when anti-Mormonism erupted into a full-scale war in Illinois and the killing of the church’s founder, Joseph Smith, in a Carthage jail, Brannan was ordered to move the East Coast Mormons out of the United States to safer ground. Brannan bought a schooner, the Brooklyn, to transport seventy men, sixty-eight women, and a hundred children. They sailed south, around Cape Horn, to what was supposed to be a sparsely populated haven in northern Mexico. They arrived in Yerba Buena, soon to be renamed San Francisco, on the last day of July 1846. The town was a sleepy place, a shack town of maybe five hundred residents. There, to Brannan’s disgust, he saw an American flag flying, signaling that California was about to become U.S. property.

Brannan didn’t bring just his people to California. He also brought his entrepreneurial skills. On the Brooklyn he had loaded a printing press, the makings of a sawmill and a flour mill, and tools of every sort. Once in San Francisco, he had the press and two mills working within weeks, and with the help of his fellow Mormons began to build a commercial empire from San Francisco to Sacramento, where he established a retail store outside the walls of Sutter’s Fort. Among his new enterprises was The California Star, one of the two newspapers that treated rather casually James Marshall’s finding of gold.

All through March and April, the Star made light of Marshall’s discovery. It was no big deal, nothing to get excited about. Meanwhile, the Star’s owner expanded his holdings in the gold fields. As a deputy of Brigham Young, he went there to collect tithes. But instead of sending the money to Salt Lake City, he used it to open a store at Mormon Island and Coloma and to build a hotel in Sacramento. He also stocked his Sacramento store with everything a gold seeker might need and gained a monopoly on steamboat landings at Sacramento. Then, on May 12, Brannan returned to San Francisco with a bottle of gold dust. Holding it high at the corner of Portsmouth Square, he shouted: “Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!” By month’s end, almost the entire male population of San Francisco had left town for the gold fields.

The U.S. military, especially, was hard hit. In San Francisco, sailors abandoned their ships, soldiers deserted by the hundreds. In Monterey, three seamen ran away from the Warren, thus forfeiting four years’ pay, and “a whole platoon of soldiers” fled the fort and “left only their colors behind.” The situation became so bad that the fort’s commanding general and the ship’s captain “had to take to the kitchen” and cook their own breakfast. Imagine, wrote one lieutenant, “a general of the United States Army” and “the commander of a man-of- war . . . in a smoking kitchen, grinding coffee, toasting a herring, and peeling an onion”!

Joining the deserters were scores of former soldiers who had recently been discharged. Out of the disbanded Mormon Battalion came several hundred. In California to acquire horses and cattle before heading to the Great Salt Lake, they now stayed to mine gold. Several hundred more gold seekers came out of the New York Volunteers, a regiment of some seven hundred men who had been recruited in New York by Colonel Jonathan Drake Stevenson, a well-heeled Democratic politician, to fight in the war against Mexico. They had been mustered into the army in August 1846, and after training for six weeks, they had been sent around Cape Horn to occupy California. Most had finished their military obligation and were now awaiting a ship home. On hearing the news of “gold on the American River,” the vast majority instead headed for the Sierras.

A month after the news broke, the American consul in San Francisco, Thomas Larkin, reported the situation to the American secretary of state. Not only had a “large portion” of the sailors and soldiers stationed in San Francisco and Sonoma deserted, but the navy had put out to sea to keep more men from joining them. In addition, three- quarters of the city’s houses were now deserted, “every blacksmith, carpenter and lawyer” was now leaving, the “brick-yards, saw-mills and ranches” had no one left to run them, both of the city’s newspapers had stopped publishing, the city had “not a justice of the peace left.”

The mammon half of Brannan’s nature thus triumphed. His businesses profited, and he became a millionaire. He acquired large holdings in both Sacramento and San Francisco. He gave up the Mormon church, never joined Brigham Young in Utah, never forwarded the tithes he received from gold-mining Mormons. Not all was rosy, however. His wife who had accompanied him to California discovered that he was a bigamist, that without her knowledge the Mormon church had given him permission to take her as a second wife, and that he was still legally married to another woman, whom he had callously abandoned along with their child. The divorce suit cost him much of his fortune. So did a lawsuit that he later filed against the railroad entrepreneurs who eventually came to dominate California. Drink finally ruined him.

The news that Brannan parlayed into a fortune traveled mainly by sea. It thus reached ports in the Pacific Ocean months before it reached New York or Boston. New York and Boston were fourteen thousand nautical miles from San Francisco, while Acapulco and Honolulu were just two thousand, Callao four thousand, Valparaiso six thousand, Sydney and Canton seven thousand.

Among the ships docked in San Francisco in May 1848 was a brig owned by José Ramón Sánchez of Valparaiso, Chile. While loading the ship with hides and tallow, California’s principal exports, the supercargo heard about gold on the American River and purchased some gold dust at $12 per ounce. On June 14 the brig set sail for Chile and arrived in Valparaiso on August 19. Within days the rush was on. Two dozen hopefuls bought passage on the Virjinia, which was just about to head north, and Chilean merchants began outfitting other ships.

Among those who lined up for passage was forty-one-year-old Vicente Pérez Rosales, a restless intellectual who already had had a colorful career as a gold miner in the Chilean Alps and a cattle rustler in Argentina. Along with his three brothers, a brother-in-law, and two servants, Rosales got passage on a French bark bound for San Francisco. The ship was jammed. All told, there were ninety male passengers, two females (including a prostitute named Rosario), four cows, eight pigs, and three dogs, along with a crew of nineteen men. The ship left Valparaiso in December 1848. Fifty-two days later, after much boredom and a few near disasters, Rosales and his shipmates reached the mouth of the Golden Gate, which, he wrote, “inspired awe but at the same time smiled, seeming to open wide to receive us.”

Meanwhile, far across the Pacific, The Sydney Herald broke the news of gold on the American River in December 1848. Among those who took notice was thirty-three-year-old Edward Hargraves, “a corpulent bull- calf of a man” who had worked as a sailor, publican, and shopkeeper. After settling his affairs at home, Hargraves formed a small group of gold seekers and bought passage on the Elizabeth Archer, an English bark out of Liverpool. On board were at least one hundred passengers. Leaving Sydney on July 17, 1849, the ship reached San Francisco eighty-one days later. As it entered the harbor, Hargraves’s hopes skyrocketed. Everywhere he looked he saw abandoned ships, “a complete forest of masts—a sight well calculated to inspire us with hope, and remove the feelings of doubt.” The next day the Elizabeth Archer joined them, as the whole crew, excepting one officer and three apprentice boys, jumped ship.

Hargraves’s high hopes soon dimmed, however. Heading well east of San Francisco, he hoped to make a fortune prospecting on the Stanislaus River. He learned the craft of prospecting with pans, cradles, and excavation, but he found little gold and nearly froze to death at night. During the day, however, he noticed that the California terrain showed similarities to that of his Australian home. Hadn’t he seen similar rocks and geological formations in New South Wales, within three hundred miles of Sydney? He was certain he had. Unsuccessful in California, he decided to return to Australia and discover gold there. Arriving in Sydney in January 1851, he proceeded to the interior, and on February 12 found gold in Lewis Ponds Creek, a small tributary of the Macquarie River. The impact was instantaneous. In 1852 Australia produced sixty million in gold, and Hargraves became a national hero.

Simultaneously, while the news of California gold was enticing Edward Hargraves and other readers of The Sydney Herald, ship brokers spread the word in southern China, especially throughout the Canton region. Why Canton? That has become a matter of dispute. According to one school of thought, the region had been devastated by civil war, floods, droughts, typhoons, and famine. Families were thus desperate, looking for a way out. According to another interpretation, the area was more market-oriented than most of China and thus had more than its share of risk takers.

Whatever the explanation, ship brokers saw the Cantonese as fair game. Playing on their hopes and fears, one enterprising Hong Kong broker concocted an illustrated pamphlet that promised “big pay, large houses, and food and clothing of the finest description” for all those who went to California. The broker also claimed that California was “a nice country, without mandarins or soldiers,” that the Chinese would be welcomed there with open arms, and that the “Chinese god” was already there.

From the Hardcover edition.

The chain of events that led to the killing began in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada on a cold morning in late January 1848. That morning, as every morning for the past several months, Jennie Wimmer had been working over a hot woodstove. Her task at the moment was making soap. Technically, she was the cook and laundress for a crew of white men, mainly Mormons, who were building a sawmill on the south fork of the American River. In fact, however, she had so alienated the Mormons that they no longer ate at her table.

Initially the men had welcomed her. Tired of their own cooking and eager to have a woman in the kitchen, they had even accepted the fact that she always served the choice portions of pork and mutton to her husband, Peter, and her seven children. But she had treated them shabbily and worn out her welcome. Whenever she rang the dinner bell, she had expected them to appear at once, and on Christmas morning, when they had taken extra time washing up, she had bawled them out, telling them that “she was Boss” and that they “must come at the first call” or go without breakfast. With that, they had “revolted from under her government” and decided to build their own separate cabin and cook for themselves.

What had made matters worse was that Jennie Wimmer wasn’t an old tyrant. She was a young one, just twenty-six years old, much younger than some of the men. She also cursed, and, like most white women in California at this time, she had been around.

Christened Elizabeth Jane, but always called Jennie, she was the daughter of a Virginia tobacco farmer who in 1838 had moved his family to Lumpkin County, Georgia, to mine gold. There she and her mother had run a boardinghouse for local miners, and there she had met a young miner named Obadiah Baiz. They had married and moved to Missouri in 1840. He had died in 1843, leaving her a widow with two children. She then married Peter Wimmer, a thirty-three-year-old widower from Cincinnati with five children. In the spring of 1846 the Wimmers decided to leave the United States and head west to Mexican California. They joined a wagon train of eighty-four migrants, trekked across the Rockies and Sierras, and arrived at Sutter’s Fort, in what is now Sacramento, on November 15, 1846.

The following spring the owner of the fort, Johann Sutter, decided to build a sawmill for his rapidly expanding agricultural empire. He, too, had been around. He had fled Switzerland for New York in 1834, leaving behind a wife and four children, large debts, and a warrant for his arrest. He then went to Missouri, New Mexico, Oregon, Hawaii, and Alaska before he reached California in 1839. Since then he had become a Mexican citizen and persuaded the governor of California to grant him a huge tract of land in the Sacramento valley, which he had dubbed New Helvetia. He was now forty-four years old and saw nothing but glory days lying ahead.

The site Sutter picked for his sawmill was some forty miles from his home base, on the south fork of the American River, in a place that came to be known as Coloma. Had Sutter been in his native Switzerland, he could have found plenty of millwrights who knew how to tap the power of falling water. But in the Sacramento valley finding a skilled millwright or even a millwright’s apprentice was next to impossible. So to oversee the operation Sutter turned to James Marshall, a thirty-seven-year-old New Jersey carpenter who had tried his hand at ranching in the Sacramento valley and failed miserably.

Sutter assigned thirteen of his Mormon hands to work under Marshall. They were part of a larger contingent of eight hundred Mormons who had been sent by Salt Lake City to earn money fighting in the Mexican War. This contingent in 1847 had come to Sutter’s Fort on their way back to Utah. About eighty had stayed to work, not for wages, but for horses and cattle to take home with them. Sutter still had nearly fifty Mormon hands. He thought that they were the best workers he had ever encountered. The men he assigned to Marshall had agreed to stay until the following spring. Then they planned to head east across the mountains to join Brigham Young and their fellow Saints on the shores of the Great Salt Lake. They, too, had been around. One of their leaders, Henry Bigler, had survived the anti-Mormon wars in Missouri and Illinois and now was an elder in the Mormon church.

Sutter also employed Maidu Indians. He essentially rented them from tribal leaders. He had for years, using some as personal servants, others to dig irrigation ditches and plant his orchards. He didn’t think much of their work habits, but they cost him much less than the Mormons, and so he decided to have one Maidu crew dig the race for his sawmill. To oversee them he hired Jennie Wimmer’s husband, Peter. The camp also needed a cook and a laundress, and for those duties Sutter hired Jennie, not knowing that her dictatorial ways would drive Henry Bigler and his fellow Mormons to the point of rebellion.

As luck would have it, however, Jennie Wimmer had one skill that the others lacked. Thanks to her time in Georgia, she knew how to tell the difference between gold and fool’s gold. That knowledge proved helpful when Peter brought to her kitchen a pebble that James Marshall had found earlier that morning in the freshly dug tail race. The find had excited Marshall, so much so that he ran back to his Mormon crew, shouting: “Boys, by God I believe I have found a gold mine!”

The workers, however, had been skeptical. They had tested the metal, biting and hammering it to see if it was brittle, and found that it was malleable. But they still had doubts. So, too, did Marshall. The chips he found just didn’t have enough luster, he thought, to be gold. Didn’t gold glisten? He wasn’t certain. Nor was Peter. But Jennie knew what to do with the pebble Peter handed her. She tossed it into a kettle of soap she was making, knowing that it would corrode if it was fool’s gold. She then finished making the soap and set it off to cool. The next morning one of the hands asked her about the pebble. “I told him it was in my soap kettle. . . . A plank was brought for me to lay my soap onto, and I cut it in chunks, but it was not to be found. At the bottom of the pot was a double handful of potash, which I lifted in my two hands, and there was my gold as bright as could be.”

James Marshall then braved a drenching rain to take the news to Sutter. He found Sutter writing at his office desk, totally surprised to see him. Hadn’t Marshall just received all the supplies he needed? To Sutter’s further surprise, Marshall then insisted that the door be locked and asked for two pails of water and a scale. He then showed Sutter what he had found, and the two men spent the next couple of hours consulting the American Encyclopedia and doing one experiment after another. They bit and hammered the metal to see if it was malleable. They doused it with nitric acid to see if it would tarnish. They weighed it against silver. They weighed it a second time—and then a third. They immersed the scales into a pail of water to see if it had greater specific gravity and sunk to the bottom. Finally, after again consulting the American Encyclopedia, they pronounced it gold.

Sutter decided that the discovery must be kept secret. The next day he rode up to Coloma. “I had a talk with my employed people all at the Sawmill” and asked “that they would do me the great favor and keep it a secret.” But he forgot to silence Jennie Wimmer and her sons. They told all who came by, including a teamster, Jacob Wittner, who carried the news back to Sutter’s Fort. Sutter himself also had loose lips, and by March the news had reached San Francisco.

The first reports were dismissed as nonsense. Legends, talk, and boasts of gold had been heard many times before. Just six years earlier, in 1842, gold had been found in the mountains just north of Los Angeles, but the find played out quickly. Maybe Coloma would just be more of the same. The two weekly San Francisco newspapers, The Californian and The California Star, treated the first reports with casual indifference.

In downplaying the reports, the Star’s owner had an ulterior motive. The newspaper belonged to Sam Brannan, a dapper and friendly man who seemingly spent half his time serving God, the other half serving mammon. A twenty-nine-year-old Maine native, Brannan had been a Mormon leader for most of his adult life. When he was fourteen years old, his sister had married a Mormon missionary, and he tagged along with the honeymoon couple to what was then the Mormon headquarters in Kirtland, Ohio. He had converted to the faith, helped build the first temple, and become a printer. He was then sent to New York City as the East Coast publisher of Mormon literature. He made valuable commercial contacts there and by age twenty-five had become a rich man.

Then, in 1844, when anti-Mormonism erupted into a full-scale war in Illinois and the killing of the church’s founder, Joseph Smith, in a Carthage jail, Brannan was ordered to move the East Coast Mormons out of the United States to safer ground. Brannan bought a schooner, the Brooklyn, to transport seventy men, sixty-eight women, and a hundred children. They sailed south, around Cape Horn, to what was supposed to be a sparsely populated haven in northern Mexico. They arrived in Yerba Buena, soon to be renamed San Francisco, on the last day of July 1846. The town was a sleepy place, a shack town of maybe five hundred residents. There, to Brannan’s disgust, he saw an American flag flying, signaling that California was about to become U.S. property.

Brannan didn’t bring just his people to California. He also brought his entrepreneurial skills. On the Brooklyn he had loaded a printing press, the makings of a sawmill and a flour mill, and tools of every sort. Once in San Francisco, he had the press and two mills working within weeks, and with the help of his fellow Mormons began to build a commercial empire from San Francisco to Sacramento, where he established a retail store outside the walls of Sutter’s Fort. Among his new enterprises was The California Star, one of the two newspapers that treated rather casually James Marshall’s finding of gold.

All through March and April, the Star made light of Marshall’s discovery. It was no big deal, nothing to get excited about. Meanwhile, the Star’s owner expanded his holdings in the gold fields. As a deputy of Brigham Young, he went there to collect tithes. But instead of sending the money to Salt Lake City, he used it to open a store at Mormon Island and Coloma and to build a hotel in Sacramento. He also stocked his Sacramento store with everything a gold seeker might need and gained a monopoly on steamboat landings at Sacramento. Then, on May 12, Brannan returned to San Francisco with a bottle of gold dust. Holding it high at the corner of Portsmouth Square, he shouted: “Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!” By month’s end, almost the entire male population of San Francisco had left town for the gold fields.

The U.S. military, especially, was hard hit. In San Francisco, sailors abandoned their ships, soldiers deserted by the hundreds. In Monterey, three seamen ran away from the Warren, thus forfeiting four years’ pay, and “a whole platoon of soldiers” fled the fort and “left only their colors behind.” The situation became so bad that the fort’s commanding general and the ship’s captain “had to take to the kitchen” and cook their own breakfast. Imagine, wrote one lieutenant, “a general of the United States Army” and “the commander of a man-of- war . . . in a smoking kitchen, grinding coffee, toasting a herring, and peeling an onion”!

Joining the deserters were scores of former soldiers who had recently been discharged. Out of the disbanded Mormon Battalion came several hundred. In California to acquire horses and cattle before heading to the Great Salt Lake, they now stayed to mine gold. Several hundred more gold seekers came out of the New York Volunteers, a regiment of some seven hundred men who had been recruited in New York by Colonel Jonathan Drake Stevenson, a well-heeled Democratic politician, to fight in the war against Mexico. They had been mustered into the army in August 1846, and after training for six weeks, they had been sent around Cape Horn to occupy California. Most had finished their military obligation and were now awaiting a ship home. On hearing the news of “gold on the American River,” the vast majority instead headed for the Sierras.

A month after the news broke, the American consul in San Francisco, Thomas Larkin, reported the situation to the American secretary of state. Not only had a “large portion” of the sailors and soldiers stationed in San Francisco and Sonoma deserted, but the navy had put out to sea to keep more men from joining them. In addition, three- quarters of the city’s houses were now deserted, “every blacksmith, carpenter and lawyer” was now leaving, the “brick-yards, saw-mills and ranches” had no one left to run them, both of the city’s newspapers had stopped publishing, the city had “not a justice of the peace left.”

The mammon half of Brannan’s nature thus triumphed. His businesses profited, and he became a millionaire. He acquired large holdings in both Sacramento and San Francisco. He gave up the Mormon church, never joined Brigham Young in Utah, never forwarded the tithes he received from gold-mining Mormons. Not all was rosy, however. His wife who had accompanied him to California discovered that he was a bigamist, that without her knowledge the Mormon church had given him permission to take her as a second wife, and that he was still legally married to another woman, whom he had callously abandoned along with their child. The divorce suit cost him much of his fortune. So did a lawsuit that he later filed against the railroad entrepreneurs who eventually came to dominate California. Drink finally ruined him.

The news that Brannan parlayed into a fortune traveled mainly by sea. It thus reached ports in the Pacific Ocean months before it reached New York or Boston. New York and Boston were fourteen thousand nautical miles from San Francisco, while Acapulco and Honolulu were just two thousand, Callao four thousand, Valparaiso six thousand, Sydney and Canton seven thousand.

Among the ships docked in San Francisco in May 1848 was a brig owned by José Ramón Sánchez of Valparaiso, Chile. While loading the ship with hides and tallow, California’s principal exports, the supercargo heard about gold on the American River and purchased some gold dust at $12 per ounce. On June 14 the brig set sail for Chile and arrived in Valparaiso on August 19. Within days the rush was on. Two dozen hopefuls bought passage on the Virjinia, which was just about to head north, and Chilean merchants began outfitting other ships.

Among those who lined up for passage was forty-one-year-old Vicente Pérez Rosales, a restless intellectual who already had had a colorful career as a gold miner in the Chilean Alps and a cattle rustler in Argentina. Along with his three brothers, a brother-in-law, and two servants, Rosales got passage on a French bark bound for San Francisco. The ship was jammed. All told, there were ninety male passengers, two females (including a prostitute named Rosario), four cows, eight pigs, and three dogs, along with a crew of nineteen men. The ship left Valparaiso in December 1848. Fifty-two days later, after much boredom and a few near disasters, Rosales and his shipmates reached the mouth of the Golden Gate, which, he wrote, “inspired awe but at the same time smiled, seeming to open wide to receive us.”

Meanwhile, far across the Pacific, The Sydney Herald broke the news of gold on the American River in December 1848. Among those who took notice was thirty-three-year-old Edward Hargraves, “a corpulent bull- calf of a man” who had worked as a sailor, publican, and shopkeeper. After settling his affairs at home, Hargraves formed a small group of gold seekers and bought passage on the Elizabeth Archer, an English bark out of Liverpool. On board were at least one hundred passengers. Leaving Sydney on July 17, 1849, the ship reached San Francisco eighty-one days later. As it entered the harbor, Hargraves’s hopes skyrocketed. Everywhere he looked he saw abandoned ships, “a complete forest of masts—a sight well calculated to inspire us with hope, and remove the feelings of doubt.” The next day the Elizabeth Archer joined them, as the whole crew, excepting one officer and three apprentice boys, jumped ship.

Hargraves’s high hopes soon dimmed, however. Heading well east of San Francisco, he hoped to make a fortune prospecting on the Stanislaus River. He learned the craft of prospecting with pans, cradles, and excavation, but he found little gold and nearly froze to death at night. During the day, however, he noticed that the California terrain showed similarities to that of his Australian home. Hadn’t he seen similar rocks and geological formations in New South Wales, within three hundred miles of Sydney? He was certain he had. Unsuccessful in California, he decided to return to Australia and discover gold there. Arriving in Sydney in January 1851, he proceeded to the interior, and on February 12 found gold in Lewis Ponds Creek, a small tributary of the Macquarie River. The impact was instantaneous. In 1852 Australia produced sixty million in gold, and Hargraves became a national hero.

Simultaneously, while the news of California gold was enticing Edward Hargraves and other readers of The Sydney Herald, ship brokers spread the word in southern China, especially throughout the Canton region. Why Canton? That has become a matter of dispute. According to one school of thought, the region had been devastated by civil war, floods, droughts, typhoons, and famine. Families were thus desperate, looking for a way out. According to another interpretation, the area was more market-oriented than most of China and thus had more than its share of risk takers.

Whatever the explanation, ship brokers saw the Cantonese as fair game. Playing on their hopes and fears, one enterprising Hong Kong broker concocted an illustrated pamphlet that promised “big pay, large houses, and food and clothing of the finest description” for all those who went to California. The broker also claimed that California was “a nice country, without mandarins or soldiers,” that the Chinese would be welcomed there with open arms, and that the “Chinese god” was already there.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Richards, a leading historian of 19th century America superbly illuminates gold rush California as a land in contention between national pro– and anti–slavery lobbies in the decade leading up to the Civil War.”

—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Richards offers a broad panorama that moves seamlessly from the gold fields to the halls of congress. This is an excellent work of popular history that will add to the appreciation of a critical epoch in our national development.”

—Booklist

“Brings to life a population of scheming officeholders, xenophobic Californians and frantic slaveholders, all of whom resorted to the ultimate frontier solution: violence.’

—Kirkus Reviews

“An engrossing chronicle of the political intrigues that engulfed California in the 1850s, when pro-Southern legislators there angled to turn the state’s newfound wealth to the benefit of the slave economy.”

—The Atlantic

“The important back-story of the Gold Rush, according to gifted historian Leonard Richards, is political and racial. Mr. Richards contends in this insightful new book, The California Gold Rush and the Coming of the Civil War that for every fortune seeker who viewed California as a place to get rich discovering gold, another believed it a place to get rich exporting, utilizing, or trafficking in human slaves. . . . [A] gripping book.”

—The New York Sun

“Richards meticulously catalogs details of 19th-century American legislation that nonspecilaists won’t have thought about since high school: the Missouri Compromise, the Gadsden Purchase, the Kansas-Nebraska Act. But when he places the actors center stage to reveal the motives behind the politics, the narrative approaches the Shakespearean.”

—Tennessean

“With a mastery that brings even his bit players to life, Leonard Richards tells a gripping story about politics, business, violence, and the scoundrels who almost destroyed the United States. If you think you already know this story, you're in for some nice surprises. And if you don’t, there’s no better guide.”

—Robin L. Einhorn, author of American Taxation, American Slavery

“Leonard Richards has once again produced a wonderful, entertaining, and informative account of antebellum politics. Most important, he shows the myriad forces–greed, ambition, idealism, racism, patronage, migration, expansionism–that melded together to distance southerners from northerners. Any one reading this work will come away with a deep understanding of how the antagonism between free and slave labor systems constituted the volatile fuel that made the explosion of secession and civil war possible.”

—James L. Huston, author of Calculating the Value of the Union: Slavery, Property Rights, and the Economic Origins of the Civil War

“A truly rollicking book, full of colorful characters, duels, hard-rock miners, ‘Chivs,’ and back-stabbing politics. But its readability belies the centrality of these seemingly minor characters to the drama of the nation’s sectional crisis. The Golden State can no longer be ignored by those wishing to tell the story of how the nation came to civil war.”

—Jonathan H. Earle, author of Jacksonian Antislavery and the Politics of Free Soil, 1824-1854

From the Hardcover edition.

—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Richards offers a broad panorama that moves seamlessly from the gold fields to the halls of congress. This is an excellent work of popular history that will add to the appreciation of a critical epoch in our national development.”

—Booklist

“Brings to life a population of scheming officeholders, xenophobic Californians and frantic slaveholders, all of whom resorted to the ultimate frontier solution: violence.’

—Kirkus Reviews

“An engrossing chronicle of the political intrigues that engulfed California in the 1850s, when pro-Southern legislators there angled to turn the state’s newfound wealth to the benefit of the slave economy.”

—The Atlantic

“The important back-story of the Gold Rush, according to gifted historian Leonard Richards, is political and racial. Mr. Richards contends in this insightful new book, The California Gold Rush and the Coming of the Civil War that for every fortune seeker who viewed California as a place to get rich discovering gold, another believed it a place to get rich exporting, utilizing, or trafficking in human slaves. . . . [A] gripping book.”

—The New York Sun

“Richards meticulously catalogs details of 19th-century American legislation that nonspecilaists won’t have thought about since high school: the Missouri Compromise, the Gadsden Purchase, the Kansas-Nebraska Act. But when he places the actors center stage to reveal the motives behind the politics, the narrative approaches the Shakespearean.”

—Tennessean

“With a mastery that brings even his bit players to life, Leonard Richards tells a gripping story about politics, business, violence, and the scoundrels who almost destroyed the United States. If you think you already know this story, you're in for some nice surprises. And if you don’t, there’s no better guide.”

—Robin L. Einhorn, author of American Taxation, American Slavery

“Leonard Richards has once again produced a wonderful, entertaining, and informative account of antebellum politics. Most important, he shows the myriad forces–greed, ambition, idealism, racism, patronage, migration, expansionism–that melded together to distance southerners from northerners. Any one reading this work will come away with a deep understanding of how the antagonism between free and slave labor systems constituted the volatile fuel that made the explosion of secession and civil war possible.”

—James L. Huston, author of Calculating the Value of the Union: Slavery, Property Rights, and the Economic Origins of the Civil War

“A truly rollicking book, full of colorful characters, duels, hard-rock miners, ‘Chivs,’ and back-stabbing politics. But its readability belies the centrality of these seemingly minor characters to the drama of the nation’s sectional crisis. The Golden State can no longer be ignored by those wishing to tell the story of how the nation came to civil war.”

—Jonathan H. Earle, author of Jacksonian Antislavery and the Politics of Free Soil, 1824-1854

From the Hardcover edition.