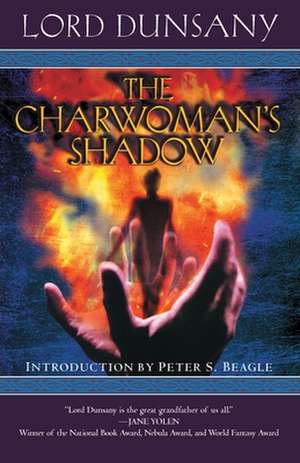

The Charwoman's Shadow: Del Rey Impact

Autor Edward John Moreton Dunsany, Dunsanyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 1999

Preț: 111.17 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 167

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.27€ • 22.21$ • 17.61£

21.27€ • 22.21$ • 17.61£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345431929

ISBN-10: 0345431928

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 141 x 216 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: Del Rey Books

Seria Del Rey Impact

ISBN-10: 0345431928

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 141 x 216 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: Del Rey Books

Seria Del Rey Impact

Notă biografică

Lord Dunsany was Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, the eighteenth baron of an ancient line. He hunted lions in Africa, taught English in Athens, fought in the Boer and Kaiserian wars, and was wounded in the service of his country. As senior peer of Ireland, he saw three sovereigns crowned at Westminster; part of the renaissance of Irish drama, he hobnobbed with Yeats and Synge and Lady Gregory during the great days of Dublin's Abbey Theatre. He was peer, sportsman, soldier, playwright, globe-trotter, and once chess champion of Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. He wrote more than sixty books before his death in 1957 and influenced some of the greatest writers of our time.

Extras

The Lord of the Tower Finds a Career for His Son

Picture a summer evening sombre and sweet over Spain, the glittering sheen of leaves fading to soberer colours, the sky in the west all soft, and mysterious as low music, and in the east like a frown. Picture the Golden Age past its wonderful zenith, and westering now towards its setting.

In such a time of day and time of year, and in such a time of history, a young man was travelling on foot on a Spanish road, from a village wellnigh unknown, towards the gloom and grandeur of mountains. And as he travelled a wind rising up with the fall of day flapped his cloak hugely about him.

The strength of the wind grew, until little strange cries were in it; the slope steepened, the daylight waned; and the man and his cloak and the evening so merged into one darkness that even in imagination I can but dimly see him now.

Let us therefore turn to such questions as who he was, and how he came to be faring at such an hour towards a region so rocky and lonely as that which loomed before him, while the latest stragglers amongst other men were nearing their houses amongst the sheltered fields.

His name was Ramon Alonzo Matthew-Mark-Luke-John of the Tower and Rocky Forest. And his father had lately called to him as he played at ball with his sister, beating it back and forth to each other over a deep yew hedge; and the ball had a row of feathers fixed all round it to make it fly gently and fairly; and the yew hedge ended at a white balustrade, and beyond that lay the wild rocks and the frown of the forest: his father called to him and he entered the house out of the mellow evening, praying his sister to wait; but he talked with his father till all the light was gone, and they played at ball no more.

And in such a manner as this spoke the Lord of the Tower and Rocky Forest to his son when they were seated before the logs in the room where the boar-spears hung. "Whether to hunt the boar or the stag be sweeter I know not; methinks the boar, but only the blessed Saints know which is truly the sweeter: and yet there are other considerations besides these, and the world were happier were it not so, yet it is ever thus." And the boy nodded his head, for he knew what it was of which his father would speak, that it was of lucre, which hath much to do with worldly affairs: the good fathers had warned him of it. And indeed of this very thing his father told.

"For however vile or dross-like," he said, "gold be in itself, and I do not ask you to doubt the ill repute you have learned of it in the school on the high hill, yet is it necessary in curious ways to many things that are good, as certain foulnesses nourish the roots of the vine. For Emanuel and Mark are of such a kind that they will have their regular payment year in year out for such work as they do with the horses, nor is Peter any better in the garden, and it is indeed the same in the dairy. And then there was the teaching that you received from the good fathers on their high hill, much of this dross went also there though the work itself was a blessed one. And now it is necessary to put yet more of this gold in a box, and to have it ready against some day when a dowry will be needed for your sister, for she is already past fifteen. And, the rocky structure of our soil being unsuited to husbandry, gold is not easily wrung from it, and there is little of a worldly nature to be won from the forest; and to

me it seems that as sin increases on Earth the need for gold grows greater.

"For myself, if the getting of gold be an art, as some have said, I am past the time for learning a new art; and, if it be a sin, my sins are over. Yet you my son may haply gather this great necessity for us, or this evil, whatever it be; and, if it be a sin, what is one more sin to youth? Not much, I fear."

The youth crossed himself.

"And follow not the way of the sword," continued his father, in no whit diverted from his discourse, "for the lawyers ever defeat it with their pens, as hath been said of old; but follow the Art, and you shall deal in a matter at whose mention lawyers pale."

"The Black Art!" exclaimed Ramon Alonzo.

"There is but one art," said his father; "and it shall all the more advantage you to follow it in that there hath been of late but little magic in Spain, and even in this forest there are not, but on rarest evenings, such mysteries nor such menace as I myself can remember; and no dragon hath been seen since my grandfather's days."

"The Black Art!" said Ramon Alonzo. "But how shall I tell of this to Father Joseph?"

And his father rubbed his chin awhile before he spoke again.

"'Twere hard indeed," he said, "to tell so good a man. Yet are we in sore need of gold, and God forbid in His mercy that one of us should ever follow a trade."

"Amen," said his son.

And the fervour with which the boy had said Amen heartened his father to hope he would do his bidding, and cheered him on the way with his discourse, which he continued as follows.

"There is dwelling in the mountains, a day's walk beyond Aragona (whose spires we see), a magician known to my father. For once my father hunting a stag in his youth went far into the mountains, as goodly a stag as ever rejoiced a hunter, though once I killed one as good but never better. I killed mine in the year of the great snowfall, the year before you were born; it had come down from the mountains. But my father hunted his up from the valley where it had been feeding all night at the edges of gardens; it went home to the mountains, and in dense woods on the slope my father killed it at evening. And then the most curious man he had ever known came down the rocks, walking gently, wearing a black silk cloak, to where he was skinning the stag with tired hounds sitting round him, and asked my father if he studied magic. And my father said that hunting the stag and the boar were the only studies he knew. And well indeed he studied them, and he taught me, but not all he knew for no man could learn so much. And

then he told the magician something of how to hunt boars; and the magician was pleased, for men shunned him much, and seldom spoke from their hearts of the things they loved, before his portentous cloak and his strange wise eye. And my father warmed to the tales as he told of the thing he had studied; and the stars came twinkling out above the magician, and the gloom was enormous in the ominous wood, and still my father told of the ways of boars, for there was never fear in my father. And the magician asked my father if there was any favour he would have of him, and my father said, 'Yes,' for he had ever wondered at the art of writing, and he asked the magician if he would write for him. And this the magician did, withdrawing a cork from a horn that hung from his girdle and that was filled with ink, and taking a goose-quill and writing there in the wood upon a little scroll that he took from a satchel. And they parted in the wood, and my father remembered that day all his years, as much for what he had see

n the magician do as for the splendid horns he had won that day. And when the writing came to be read it was seen that it was a letter of friendship or welcome to my father or to whomever he should send with that scroll to the house in the wood.

"Now my father cared only to hunt the boar and the stag and had no need of magic, and I have had nothing to do with parchments nor writings. But I can find the scroll at this moment among the tusks of boars that my father laid by, and you shall have the scroll and go to the wood and say to that magician, 'I am the grandson of him that taught you of the taking of boars nigh eighty years agone.'"

"But will he yet live?" asked Ramon.

"He were no magician else," replied his father.

And the boy sat silent then, regretting the thoughtlessness that his hasty words had revealed.

"With the mystery of writing, which you will doubtless study there, I have myself some acquaintance, having sufficiently studied the matter, some while since, to be able to practise it should the occasion ever arise: but of all mysteries that he hath the skill to teach you the one to study most diligently is that one which concerns the making of gold. Yes, yes," he said, silencing with a wave or two of his hand some hasty youthful objection that he saw on the boy's lips, "I wot well the sin that is inherent in gold, yet methinks there is some primal curse upon it, put there by Satan before it was laid in earth, which may not cling to the gold that philosophers make."

And youth and haste again urged another question. "But can the philosophers make gold?" blurted out Ramon Alonzo.

"Ill-informed lad," said his father, "have you heard of no philosophers during the last ten centuries seeking for gold with their stone?"

"Yes," answered Ramon Alonzo, "but I heard of none that found it."

And his father shook his head with tolerant smiles and answered nothing at once, not hastening to reprove the lad's ill-founded opinion, for the wisdom of age expects these light conclusions from youth. And then he instructed his son in simple words, telling him that the value of gold lies not in any especial power in the metal, but purely in its rarity; and explaining so that a child could have understood, that had these most learned of men who gave their lives to alchemy acquainted the vulgar with the fruits of their study, as soon as their art had taught them the way of transmuting base metal, they would have undone in one garrulous moment the advantage that they had earned by nights of toil, working in lonely towers while all the world had rest. And more simple arguments he added, sufficient to correct the hasty error of youth, but too obvious and trite to offer to the attention of my reader. Having then explained that the philosopher's stone must have been often found and put to the use for which it wa

s intended, he recommended the study of it once more to his son. And the young man weighed the advantages of gold with all that he had learned in its disfavour, and there and then decided to follow that study. Gladly then the Lord of the Tower and Rocky Forest went to this rummage-room where strange things lay and none interfered with the spider. And in that dim place where one scarce could have hoped to find anything, amongst heaps of old fishing nets that had become solid with dust, where worn-out boar-spears lay on the floor, and rusted bandilleros that had once pricked famous bulls, blunt knives and broken tent-pegs, and things too old for one to be able to name them at all, unless one washed them and brought them out in the light, groping amongst all these the Lord of the Tower found a pale heap of boars' tusks, and the scroll amongst them, as he had told his son: then he left the place to the spider. And returning with the scroll to his son he brought also a coffer out of another room, a small stout bo

x of oak and massive silver, well guarded by a great lock, all lined within with satin. And he took a great key and carefully unlocked it, and showed it to Ramon Alonzo as he gave him the scroll of the magician; he held the coffer open with the light blue satin showing and said never a word; the young man knew it for the coffer of his sister's dowry and saw that it was empty. And by the time his father had closed the box again, and carefully locked it and placed the key in safety, the boy's young thoughts had roamed away to beyond Aragona to the man with the black silk cloak and his house in the wood, where base metals would have to suffer wonderful changes before good thick pieces of dross should chink deep on that satin lining. And where young thoughts have roamed there soon follow lads or maidens.

And then they talked of the way beyond Aragona, and the path that led to the wood. And the father leaned in his chair in comfort at ease, for it wearied him to speak of things that are hard to understand, and especially the getting of money; and he had thought of this matter for days before he had spoken of it, and it had never seemed sure to him that the money would come at all, but now all seemed clear and he rested. And leaning back in his chair he told the way to his son, which was easy as far as the wood, and after that he could ask the way of such men as he met; and if he met none he was likely near to the house, for men avoided it much. Awhile they talked of things of little moment, small matters pleasant to both, till the father remembered that more than this was seemly, and reminded his son of all such things as he himself knew that concerned the decorum and gravity of the study of magic. Indeed he knew little of this ancient study, but had once seen a conjuror produce a rabbit alive from under an em

pty sombrero, years ago outside a village in which he had sought to purchase a cow, and it was this that he meant when he spoke of the slight acquaintance he had himself had with magic; for the rest he spoke of the hoar traditions of magic, which were as antique then as now, for then as now they went back past the first gates of history, and ran far on the wide plains of legend and into the dimness of time.

"To such traditions," he said, "a grave decorum were fitting."

And the young man nodded his head, his face full of a fitting decorum. And the father remembered his own youth and wondered.

They parted then, the Lord of the Tower and Rocky Forest going to find his lady, the young man still in his chair before the fire, pondering his journey and his future calling. These thoughts were too swift to follow: pursuing instead the slow steps of his father we find him come to a room in which, already, discernible shadows were cast by a want of gold. With its ancient sentinel chairs that seemed posted there to check lounging, and its treasures of tapestries hung to hide ruined panels or wherever the draughts blew most from untended rat-holes, that threatened room would scarce convey to our minds, could we see it across the centuries, any hint of impending need. And yet those shadows were there, moving softly as in slow dances with the solemn folds of the tapestry, or rising to welcome draughts in their secret manner, or lurking by the huge carved feet of the chairs; and always knowing with shadow-knowledge and whispering with shadow-talk, and hinting and prophesying and fearing, that a need was nearing

the Tower to trouble its years. And here the Lord of the Tower found his lady, whose hair was whitening above a face unperturbed by the passing of time or anything that time brings; if great passions had shaken her mind or wandering imaginations often troubled it, they had passed across that plump and placid face with no more traces than the storms and the ships leave on the yellow sand of a sunny cove.

And he said to her: "I have spoken with Ramon Alonzo and have arranged everything with him. He is to leave us soon to work with a learned man that lives beyond Aragona, and will win for us the gold that we require and, afterwards, some more for himself."

More than this he did not say upon that matter, for it was not his way, nor was it then the custom in Spain to speak of business to ladies.

And the lady rejoiced at this, for she had long tried to make her husband see that need that was sending its shadows to creep through the Tower, telling every nook of its coming; but the boars had to be hunted, and the hounds had to be fed, and a hundred things demanded his attention, so that she feared he might never have leisure to give his mind to this matter. But now it was all settled.

"Will Ramon Alonzo start soon?" she said.

"Not for some days," said he. "There is no haste."

But Ramon Alonzo's swifter thoughts had outpaced all this. He was speaking now with his sister, telling her that he was to start next morning for that old house in the mountains of which they had often heard tales, and bidding her tend his great boar-hound. They were in the garden though the gloaming was fading away, the garden that met the lawn on which they had lately played, a little lower down the slope where the Tower stood, and shut from the untamed earth and the rocks that were there before man by the same balustrade of marble that guarded the lawn. The hawk-moths appeared out of the darkening air from their deep homes in the forest and hovered by heavy blossoms; it was in the midst of the days that are poised between Spring and Summer. Here Ramon and Mirandola said farewell in the little paths along which they often had played in years that appeared remote to them, under Spanish shrubs that were tall fountains of flowers. And whatever the lady of the Tower guessed, neither her lord nor Ramon Alonzo h

ad any knowledge that there was a glittering flash in the eyes of the slender girl that might laugh away demands for any dowry, and be deadlier and sweeter than gold, and might mock the men that sought it and bring their plans to derision, and overturn their illusion and fill their dreams with its ashes. Ramon Alonzo was troubled by no such fancy as this as he spoke earnestly of his boar-hound, and as they spoke of his needs of combing and feeding and dryness they walked back to the Tower; and the gloaming was not yet gone, but it was midnight in Mirandola's hair.

And so it was that on the following day, at evening, beyond Aragona, a young man was to be seen by such eyes as could peer so far, in his cloak on a rocky road with his back to the sheltered fields, bound for the mountain upon which frowned the woods; and night and a moaning wind were rising all round about him.

Picture a summer evening sombre and sweet over Spain, the glittering sheen of leaves fading to soberer colours, the sky in the west all soft, and mysterious as low music, and in the east like a frown. Picture the Golden Age past its wonderful zenith, and westering now towards its setting.

In such a time of day and time of year, and in such a time of history, a young man was travelling on foot on a Spanish road, from a village wellnigh unknown, towards the gloom and grandeur of mountains. And as he travelled a wind rising up with the fall of day flapped his cloak hugely about him.

The strength of the wind grew, until little strange cries were in it; the slope steepened, the daylight waned; and the man and his cloak and the evening so merged into one darkness that even in imagination I can but dimly see him now.

Let us therefore turn to such questions as who he was, and how he came to be faring at such an hour towards a region so rocky and lonely as that which loomed before him, while the latest stragglers amongst other men were nearing their houses amongst the sheltered fields.

His name was Ramon Alonzo Matthew-Mark-Luke-John of the Tower and Rocky Forest. And his father had lately called to him as he played at ball with his sister, beating it back and forth to each other over a deep yew hedge; and the ball had a row of feathers fixed all round it to make it fly gently and fairly; and the yew hedge ended at a white balustrade, and beyond that lay the wild rocks and the frown of the forest: his father called to him and he entered the house out of the mellow evening, praying his sister to wait; but he talked with his father till all the light was gone, and they played at ball no more.

And in such a manner as this spoke the Lord of the Tower and Rocky Forest to his son when they were seated before the logs in the room where the boar-spears hung. "Whether to hunt the boar or the stag be sweeter I know not; methinks the boar, but only the blessed Saints know which is truly the sweeter: and yet there are other considerations besides these, and the world were happier were it not so, yet it is ever thus." And the boy nodded his head, for he knew what it was of which his father would speak, that it was of lucre, which hath much to do with worldly affairs: the good fathers had warned him of it. And indeed of this very thing his father told.

"For however vile or dross-like," he said, "gold be in itself, and I do not ask you to doubt the ill repute you have learned of it in the school on the high hill, yet is it necessary in curious ways to many things that are good, as certain foulnesses nourish the roots of the vine. For Emanuel and Mark are of such a kind that they will have their regular payment year in year out for such work as they do with the horses, nor is Peter any better in the garden, and it is indeed the same in the dairy. And then there was the teaching that you received from the good fathers on their high hill, much of this dross went also there though the work itself was a blessed one. And now it is necessary to put yet more of this gold in a box, and to have it ready against some day when a dowry will be needed for your sister, for she is already past fifteen. And, the rocky structure of our soil being unsuited to husbandry, gold is not easily wrung from it, and there is little of a worldly nature to be won from the forest; and to

me it seems that as sin increases on Earth the need for gold grows greater.

"For myself, if the getting of gold be an art, as some have said, I am past the time for learning a new art; and, if it be a sin, my sins are over. Yet you my son may haply gather this great necessity for us, or this evil, whatever it be; and, if it be a sin, what is one more sin to youth? Not much, I fear."

The youth crossed himself.

"And follow not the way of the sword," continued his father, in no whit diverted from his discourse, "for the lawyers ever defeat it with their pens, as hath been said of old; but follow the Art, and you shall deal in a matter at whose mention lawyers pale."

"The Black Art!" exclaimed Ramon Alonzo.

"There is but one art," said his father; "and it shall all the more advantage you to follow it in that there hath been of late but little magic in Spain, and even in this forest there are not, but on rarest evenings, such mysteries nor such menace as I myself can remember; and no dragon hath been seen since my grandfather's days."

"The Black Art!" said Ramon Alonzo. "But how shall I tell of this to Father Joseph?"

And his father rubbed his chin awhile before he spoke again.

"'Twere hard indeed," he said, "to tell so good a man. Yet are we in sore need of gold, and God forbid in His mercy that one of us should ever follow a trade."

"Amen," said his son.

And the fervour with which the boy had said Amen heartened his father to hope he would do his bidding, and cheered him on the way with his discourse, which he continued as follows.

"There is dwelling in the mountains, a day's walk beyond Aragona (whose spires we see), a magician known to my father. For once my father hunting a stag in his youth went far into the mountains, as goodly a stag as ever rejoiced a hunter, though once I killed one as good but never better. I killed mine in the year of the great snowfall, the year before you were born; it had come down from the mountains. But my father hunted his up from the valley where it had been feeding all night at the edges of gardens; it went home to the mountains, and in dense woods on the slope my father killed it at evening. And then the most curious man he had ever known came down the rocks, walking gently, wearing a black silk cloak, to where he was skinning the stag with tired hounds sitting round him, and asked my father if he studied magic. And my father said that hunting the stag and the boar were the only studies he knew. And well indeed he studied them, and he taught me, but not all he knew for no man could learn so much. And

then he told the magician something of how to hunt boars; and the magician was pleased, for men shunned him much, and seldom spoke from their hearts of the things they loved, before his portentous cloak and his strange wise eye. And my father warmed to the tales as he told of the thing he had studied; and the stars came twinkling out above the magician, and the gloom was enormous in the ominous wood, and still my father told of the ways of boars, for there was never fear in my father. And the magician asked my father if there was any favour he would have of him, and my father said, 'Yes,' for he had ever wondered at the art of writing, and he asked the magician if he would write for him. And this the magician did, withdrawing a cork from a horn that hung from his girdle and that was filled with ink, and taking a goose-quill and writing there in the wood upon a little scroll that he took from a satchel. And they parted in the wood, and my father remembered that day all his years, as much for what he had see

n the magician do as for the splendid horns he had won that day. And when the writing came to be read it was seen that it was a letter of friendship or welcome to my father or to whomever he should send with that scroll to the house in the wood.

"Now my father cared only to hunt the boar and the stag and had no need of magic, and I have had nothing to do with parchments nor writings. But I can find the scroll at this moment among the tusks of boars that my father laid by, and you shall have the scroll and go to the wood and say to that magician, 'I am the grandson of him that taught you of the taking of boars nigh eighty years agone.'"

"But will he yet live?" asked Ramon.

"He were no magician else," replied his father.

And the boy sat silent then, regretting the thoughtlessness that his hasty words had revealed.

"With the mystery of writing, which you will doubtless study there, I have myself some acquaintance, having sufficiently studied the matter, some while since, to be able to practise it should the occasion ever arise: but of all mysteries that he hath the skill to teach you the one to study most diligently is that one which concerns the making of gold. Yes, yes," he said, silencing with a wave or two of his hand some hasty youthful objection that he saw on the boy's lips, "I wot well the sin that is inherent in gold, yet methinks there is some primal curse upon it, put there by Satan before it was laid in earth, which may not cling to the gold that philosophers make."

And youth and haste again urged another question. "But can the philosophers make gold?" blurted out Ramon Alonzo.

"Ill-informed lad," said his father, "have you heard of no philosophers during the last ten centuries seeking for gold with their stone?"

"Yes," answered Ramon Alonzo, "but I heard of none that found it."

And his father shook his head with tolerant smiles and answered nothing at once, not hastening to reprove the lad's ill-founded opinion, for the wisdom of age expects these light conclusions from youth. And then he instructed his son in simple words, telling him that the value of gold lies not in any especial power in the metal, but purely in its rarity; and explaining so that a child could have understood, that had these most learned of men who gave their lives to alchemy acquainted the vulgar with the fruits of their study, as soon as their art had taught them the way of transmuting base metal, they would have undone in one garrulous moment the advantage that they had earned by nights of toil, working in lonely towers while all the world had rest. And more simple arguments he added, sufficient to correct the hasty error of youth, but too obvious and trite to offer to the attention of my reader. Having then explained that the philosopher's stone must have been often found and put to the use for which it wa

s intended, he recommended the study of it once more to his son. And the young man weighed the advantages of gold with all that he had learned in its disfavour, and there and then decided to follow that study. Gladly then the Lord of the Tower and Rocky Forest went to this rummage-room where strange things lay and none interfered with the spider. And in that dim place where one scarce could have hoped to find anything, amongst heaps of old fishing nets that had become solid with dust, where worn-out boar-spears lay on the floor, and rusted bandilleros that had once pricked famous bulls, blunt knives and broken tent-pegs, and things too old for one to be able to name them at all, unless one washed them and brought them out in the light, groping amongst all these the Lord of the Tower found a pale heap of boars' tusks, and the scroll amongst them, as he had told his son: then he left the place to the spider. And returning with the scroll to his son he brought also a coffer out of another room, a small stout bo

x of oak and massive silver, well guarded by a great lock, all lined within with satin. And he took a great key and carefully unlocked it, and showed it to Ramon Alonzo as he gave him the scroll of the magician; he held the coffer open with the light blue satin showing and said never a word; the young man knew it for the coffer of his sister's dowry and saw that it was empty. And by the time his father had closed the box again, and carefully locked it and placed the key in safety, the boy's young thoughts had roamed away to beyond Aragona to the man with the black silk cloak and his house in the wood, where base metals would have to suffer wonderful changes before good thick pieces of dross should chink deep on that satin lining. And where young thoughts have roamed there soon follow lads or maidens.

And then they talked of the way beyond Aragona, and the path that led to the wood. And the father leaned in his chair in comfort at ease, for it wearied him to speak of things that are hard to understand, and especially the getting of money; and he had thought of this matter for days before he had spoken of it, and it had never seemed sure to him that the money would come at all, but now all seemed clear and he rested. And leaning back in his chair he told the way to his son, which was easy as far as the wood, and after that he could ask the way of such men as he met; and if he met none he was likely near to the house, for men avoided it much. Awhile they talked of things of little moment, small matters pleasant to both, till the father remembered that more than this was seemly, and reminded his son of all such things as he himself knew that concerned the decorum and gravity of the study of magic. Indeed he knew little of this ancient study, but had once seen a conjuror produce a rabbit alive from under an em

pty sombrero, years ago outside a village in which he had sought to purchase a cow, and it was this that he meant when he spoke of the slight acquaintance he had himself had with magic; for the rest he spoke of the hoar traditions of magic, which were as antique then as now, for then as now they went back past the first gates of history, and ran far on the wide plains of legend and into the dimness of time.

"To such traditions," he said, "a grave decorum were fitting."

And the young man nodded his head, his face full of a fitting decorum. And the father remembered his own youth and wondered.

They parted then, the Lord of the Tower and Rocky Forest going to find his lady, the young man still in his chair before the fire, pondering his journey and his future calling. These thoughts were too swift to follow: pursuing instead the slow steps of his father we find him come to a room in which, already, discernible shadows were cast by a want of gold. With its ancient sentinel chairs that seemed posted there to check lounging, and its treasures of tapestries hung to hide ruined panels or wherever the draughts blew most from untended rat-holes, that threatened room would scarce convey to our minds, could we see it across the centuries, any hint of impending need. And yet those shadows were there, moving softly as in slow dances with the solemn folds of the tapestry, or rising to welcome draughts in their secret manner, or lurking by the huge carved feet of the chairs; and always knowing with shadow-knowledge and whispering with shadow-talk, and hinting and prophesying and fearing, that a need was nearing

the Tower to trouble its years. And here the Lord of the Tower found his lady, whose hair was whitening above a face unperturbed by the passing of time or anything that time brings; if great passions had shaken her mind or wandering imaginations often troubled it, they had passed across that plump and placid face with no more traces than the storms and the ships leave on the yellow sand of a sunny cove.

And he said to her: "I have spoken with Ramon Alonzo and have arranged everything with him. He is to leave us soon to work with a learned man that lives beyond Aragona, and will win for us the gold that we require and, afterwards, some more for himself."

More than this he did not say upon that matter, for it was not his way, nor was it then the custom in Spain to speak of business to ladies.

And the lady rejoiced at this, for she had long tried to make her husband see that need that was sending its shadows to creep through the Tower, telling every nook of its coming; but the boars had to be hunted, and the hounds had to be fed, and a hundred things demanded his attention, so that she feared he might never have leisure to give his mind to this matter. But now it was all settled.

"Will Ramon Alonzo start soon?" she said.

"Not for some days," said he. "There is no haste."

But Ramon Alonzo's swifter thoughts had outpaced all this. He was speaking now with his sister, telling her that he was to start next morning for that old house in the mountains of which they had often heard tales, and bidding her tend his great boar-hound. They were in the garden though the gloaming was fading away, the garden that met the lawn on which they had lately played, a little lower down the slope where the Tower stood, and shut from the untamed earth and the rocks that were there before man by the same balustrade of marble that guarded the lawn. The hawk-moths appeared out of the darkening air from their deep homes in the forest and hovered by heavy blossoms; it was in the midst of the days that are poised between Spring and Summer. Here Ramon and Mirandola said farewell in the little paths along which they often had played in years that appeared remote to them, under Spanish shrubs that were tall fountains of flowers. And whatever the lady of the Tower guessed, neither her lord nor Ramon Alonzo h

ad any knowledge that there was a glittering flash in the eyes of the slender girl that might laugh away demands for any dowry, and be deadlier and sweeter than gold, and might mock the men that sought it and bring their plans to derision, and overturn their illusion and fill their dreams with its ashes. Ramon Alonzo was troubled by no such fancy as this as he spoke earnestly of his boar-hound, and as they spoke of his needs of combing and feeding and dryness they walked back to the Tower; and the gloaming was not yet gone, but it was midnight in Mirandola's hair.

And so it was that on the following day, at evening, beyond Aragona, a young man was to be seen by such eyes as could peer so far, in his cloak on a rocky road with his back to the sheltered fields, bound for the mountain upon which frowned the woods; and night and a moaning wind were rising all round about him.

Recenzii

"Lord Dunsany is the great grandfather of us all."

--JANE YOLEN

Winner of the National Book Award,

Nebula Award, and World Fantasy Award

"Lord Dunsany is the fountainhead of all twentieth-century fantasy. He was certainly the finest inventor of titles ever to grace English Literature."

--DAVE DUNCAN

Author of The Gilded Chain

"How wonderful that Del Rey is bringing back The Charwoman's Shadow and The King of Elfland's Daughter for readers, new and old alike, to discover them anew. It will be a delight to read it for the first time again."

--DENNIS L. MCKIERNAN

Author the Hèl's Crucible duology

"No one can understand modern fantasy without understanding its roots, and Lord Dunsany's work is immensely significant as well as enjoyable, even today."

--KATHERINE KERR

--JANE YOLEN

Winner of the National Book Award,

Nebula Award, and World Fantasy Award

"Lord Dunsany is the fountainhead of all twentieth-century fantasy. He was certainly the finest inventor of titles ever to grace English Literature."

--DAVE DUNCAN

Author of The Gilded Chain

"How wonderful that Del Rey is bringing back The Charwoman's Shadow and The King of Elfland's Daughter for readers, new and old alike, to discover them anew. It will be a delight to read it for the first time again."

--DENNIS L. MCKIERNAN

Author the Hèl's Crucible duology

"No one can understand modern fantasy without understanding its roots, and Lord Dunsany's work is immensely significant as well as enjoyable, even today."

--KATHERINE KERR

Textul de pe ultima copertă

An old woman who spends her days scrubbing the floors might be an unlikely damsel in distress, but Lord Dunsany proves once again his mastery of the fantastical. The Charwoman's Shadow is a beautiful tale of a sorcerer's apprentice who discovers his master's nefarious usage of stolen shadows, and vows to save the charwoman from her slavery.