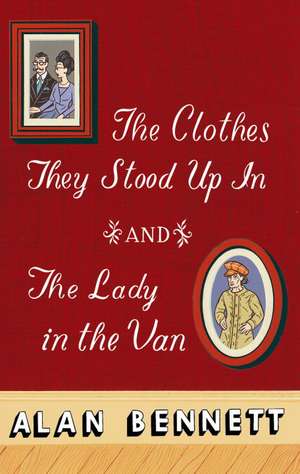

The Clothes They Stood Up in and the Lady and the Van

Autor Alan Bennetten Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2002

In “The Lady in the Van,” which The Village Voice called “one of the finest bursts of comic writing the twentieth century has produced,” Bennett recounts the strange life of Miss Shepherd, a London eccentric who parked her van (overstuffed with decades’ worth of old clothes, oozing batteries, and kitchen utensils still in their original packaging) in the author’s driveway for more than fifteen years. A mesmerizing portrait of an outsider with an acquisitive taste and an indomitable spirit, this biographical essay is drawn with equal parts fascination and compassion.

Preț: 99.12 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 149

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.97€ • 19.84$ • 15.76£

18.97€ • 19.84$ • 15.76£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 12-26 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812969658

ISBN-10: 0812969650

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 131 x 204 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0812969650

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 131 x 204 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Alan Bennett is the author of the number-one British bestseller Writing Home. He is a renowned playwright and essayist, whose screenplay for The Madness of King George was nominated for an Academy Award.

Extras

From The Clothes They Stood Up In

The Ransomes had been burgled. "Robbed," Mrs. Ransome said. "Burgled," Mr. Ransome corrected. Premises were burgled; persons were robbed. Mr. Ransome was a solicitor by profession and thought words mattered. Though "burgled" was the wrong word too. Burglars select; they pick; they remove one item and ignore others. There is a limit to what burglars can take: they seldom take easy chairs, for example, and even more seldom settees. These burglars did. They took everything.

The Ransomes had been to the opera, to Così fan tutte (or Così as Mrs. Ransome had learned to call it). Mozart played an important part in their marriage. They had no children and but for Mozart would probably have split up years ago. Mr. Ransome always took a bath when he came home from work and then he had his supper. After supper he took another bath, this time in Mozart. He wallowed in Mozart; he luxuriated in him; he let the little Viennese soak away all the dirt and disgustingness he had had to sit through in his office all day. On this particular evening he had been to the public baths, Covent Garden, where their seats were immediately behind the Home Secretary. He too was taking a bath and washing away the cares of his day, cares, if only in the form of a statistic, that were about to include the Ransomes.

On a normal evening, though, Mr. Ransome shared his bath with no one, Mozart coming personalized via his headphones and a stack of complex and finely balanced stereo equipment that Mrs. Ransome was never allowed to touch. She blamed the stereo for the burglary as that was what the robbers were probably after in the first place. The theft of stereos is common; the theft of fitted carpets is not.

"Perhaps they wrapped the stereo in the carpet," said Mrs. Ransome.

Mr. Ransome shuddered and said her fur coat was more likely, whereupon Mrs. Ransome started crying again.

It had not been much of a Così. Mrs. Ransome could not follow the plot and Mr. Ransome, who never tried, found the performance did not compare with the four recordings he possessed of the work. The acting he invariably found distracting. "None of them knows what to do with their arms," he said to his wife in the interval. Mrs. Ransome thought it probably went further than their arms but did not say so. She was wondering if the casserole she had left in the oven would get too dry at Gas Mark 4. Perhaps 3 would have been better. Dry it may well have been but there was no need to have worried. The thieves took the oven and the casserole with it.

The Ransomes lived in an Edwardian block of flats the color of ox blood not far from Regent's Park. It was handy for the City, though Mrs. Ransome would have preferred something farther out, seeing herself with a trug in a garden, vaguely. But she was not gifted in that direction. An African violet that her cleaning lady had given her at Christmas had finally given up the ghost that very morning and she had been forced to hide it in the wardrobe out of Mrs. Clegg's way. More wasted effort. The wardrobe had gone too.

They had no neighbors to speak of, or seldom to. Occasionally they ran into people in the lift and both parties would smile cautiously. Once they had asked some newcomers on their floor around to sherry, but he had turned out to be what he called "a big band freak" and she had been a dental receptionist with a timeshare in Portugal, so one way and another it had been an awkward evening and they had never repeated the experience. These days the turnover of tenants seemed increasingly rapid and the lift more and more wayward. People were always moving in and out again, some of them Arabs.

"I mean," said Mrs. Ransome, "it's getting like a hotel."

"I wish you wouldn't keep saying 'I mean,' " said Mr. Ransome. "It adds nothing to the sense."

He got enough of what he called "this sloppy way of talking" at work; the least he could ask for at home, he felt, was correct English. So Mrs. Ransome, who normally had very little to say, now tended to say even less.

When the Ransomes had moved into Naseby Mansions the flats boasted a commissionaire in a plum- colored uniform that matched the color of the building. He had died one afternoon in 1982 as he was hailing a taxi for Mrs. Brabourne on the second floor, who had forgone it in order to let it take him to hospital. None of his successors had shown the same zeal in office or pride in the uniform and eventually the function of commissionaire had merged with that of the caretaker, who was never to be found on the door and seldom to be found anywhere, his lair a hot scullery behind the boiler room where he slept much of the day in an armchair that had been thrown out by one of the tenants.

On the night in question the caretaker was asleep, though unusually for him not in the armchair but at the theater. On the lookout for a classier type of girl he had decided to attend an adult education course where he had opted to study English; given the opportunity, he had told the lecturer, he would like to become a voracious reader. The lecturer had some exciting though not very well formulated ideas about art and the workplace, and learning he was a caretaker had got him tickets for the play of the same name, thinking the resultant insights would be a stimulant to group interaction. It was an evening the caretaker found no more satisfying than the Ransomes did Così and the insights he gleaned limited: "So far as your actual caretaking was concerned," he reported to the class, "it was bollocks." The lecturer consoled himself with the hope that, unknown to the caretaker, the evening might have opened doors. In this he was right: the doors in question belonged to the Ransomes' flat.

The Ransomes had been burgled. "Robbed," Mrs. Ransome said. "Burgled," Mr. Ransome corrected. Premises were burgled; persons were robbed. Mr. Ransome was a solicitor by profession and thought words mattered. Though "burgled" was the wrong word too. Burglars select; they pick; they remove one item and ignore others. There is a limit to what burglars can take: they seldom take easy chairs, for example, and even more seldom settees. These burglars did. They took everything.

The Ransomes had been to the opera, to Così fan tutte (or Così as Mrs. Ransome had learned to call it). Mozart played an important part in their marriage. They had no children and but for Mozart would probably have split up years ago. Mr. Ransome always took a bath when he came home from work and then he had his supper. After supper he took another bath, this time in Mozart. He wallowed in Mozart; he luxuriated in him; he let the little Viennese soak away all the dirt and disgustingness he had had to sit through in his office all day. On this particular evening he had been to the public baths, Covent Garden, where their seats were immediately behind the Home Secretary. He too was taking a bath and washing away the cares of his day, cares, if only in the form of a statistic, that were about to include the Ransomes.

On a normal evening, though, Mr. Ransome shared his bath with no one, Mozart coming personalized via his headphones and a stack of complex and finely balanced stereo equipment that Mrs. Ransome was never allowed to touch. She blamed the stereo for the burglary as that was what the robbers were probably after in the first place. The theft of stereos is common; the theft of fitted carpets is not.

"Perhaps they wrapped the stereo in the carpet," said Mrs. Ransome.

Mr. Ransome shuddered and said her fur coat was more likely, whereupon Mrs. Ransome started crying again.

It had not been much of a Così. Mrs. Ransome could not follow the plot and Mr. Ransome, who never tried, found the performance did not compare with the four recordings he possessed of the work. The acting he invariably found distracting. "None of them knows what to do with their arms," he said to his wife in the interval. Mrs. Ransome thought it probably went further than their arms but did not say so. She was wondering if the casserole she had left in the oven would get too dry at Gas Mark 4. Perhaps 3 would have been better. Dry it may well have been but there was no need to have worried. The thieves took the oven and the casserole with it.

The Ransomes lived in an Edwardian block of flats the color of ox blood not far from Regent's Park. It was handy for the City, though Mrs. Ransome would have preferred something farther out, seeing herself with a trug in a garden, vaguely. But she was not gifted in that direction. An African violet that her cleaning lady had given her at Christmas had finally given up the ghost that very morning and she had been forced to hide it in the wardrobe out of Mrs. Clegg's way. More wasted effort. The wardrobe had gone too.

They had no neighbors to speak of, or seldom to. Occasionally they ran into people in the lift and both parties would smile cautiously. Once they had asked some newcomers on their floor around to sherry, but he had turned out to be what he called "a big band freak" and she had been a dental receptionist with a timeshare in Portugal, so one way and another it had been an awkward evening and they had never repeated the experience. These days the turnover of tenants seemed increasingly rapid and the lift more and more wayward. People were always moving in and out again, some of them Arabs.

"I mean," said Mrs. Ransome, "it's getting like a hotel."

"I wish you wouldn't keep saying 'I mean,' " said Mr. Ransome. "It adds nothing to the sense."

He got enough of what he called "this sloppy way of talking" at work; the least he could ask for at home, he felt, was correct English. So Mrs. Ransome, who normally had very little to say, now tended to say even less.

When the Ransomes had moved into Naseby Mansions the flats boasted a commissionaire in a plum- colored uniform that matched the color of the building. He had died one afternoon in 1982 as he was hailing a taxi for Mrs. Brabourne on the second floor, who had forgone it in order to let it take him to hospital. None of his successors had shown the same zeal in office or pride in the uniform and eventually the function of commissionaire had merged with that of the caretaker, who was never to be found on the door and seldom to be found anywhere, his lair a hot scullery behind the boiler room where he slept much of the day in an armchair that had been thrown out by one of the tenants.

On the night in question the caretaker was asleep, though unusually for him not in the armchair but at the theater. On the lookout for a classier type of girl he had decided to attend an adult education course where he had opted to study English; given the opportunity, he had told the lecturer, he would like to become a voracious reader. The lecturer had some exciting though not very well formulated ideas about art and the workplace, and learning he was a caretaker had got him tickets for the play of the same name, thinking the resultant insights would be a stimulant to group interaction. It was an evening the caretaker found no more satisfying than the Ransomes did Così and the insights he gleaned limited: "So far as your actual caretaking was concerned," he reported to the class, "it was bollocks." The lecturer consoled himself with the hope that, unknown to the caretaker, the evening might have opened doors. In this he was right: the doors in question belonged to the Ransomes' flat.

Recenzii

“[The Clothes They Stood Up In is an] absolutely delicious, near perfect little book. You will read it in a couple of hours at most, but you will think about it for a long, long time.”

-Jonathan Yardley, The Washington Post Book World

“[The Clothes They Stood Up In is] a completely charming entertainment: a small gem by one of Britain’s most versatile and gifted writers.”

-Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

“One of the top ten books of 2001.”

-Jonathan Yardley, The Washington Post Book World

“Full of jolly, broad, and very English humour...a charm-filled holiday read.”

-Alain de Botton

“Sharp...a happy evening’s read and a tantalizing mental challenge to those of us who, like the Ransomes, find [our] lives encumbered and [our] senses blunted by too much stuff.”

-Brooke Allen, The New York Times Book Review

-Jonathan Yardley, The Washington Post Book World

“[The Clothes They Stood Up In is] a completely charming entertainment: a small gem by one of Britain’s most versatile and gifted writers.”

-Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

“One of the top ten books of 2001.”

-Jonathan Yardley, The Washington Post Book World

“Full of jolly, broad, and very English humour...a charm-filled holiday read.”

-Alain de Botton

“Sharp...a happy evening’s read and a tantalizing mental challenge to those of us who, like the Ransomes, find [our] lives encumbered and [our] senses blunted by too much stuff.”

-Brooke Allen, The New York Times Book Review