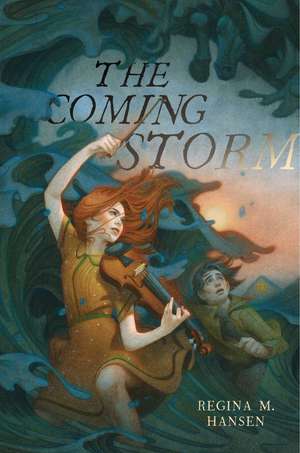

The Coming Storm

Autor Regina M. Hansenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 20 iul 2022 – vârsta de la 9 ani

There’s a certain wild magic in the salt air and the thrum of the sea. Beet MacNeill has known this all her life. It added spice to her childhood adventures with her older cousin, Gerry, the two of them thick as thieves as they explored their Prince Edward Island home. So when Gerry comes up the path one early spring morning, Beet thinks nothing of it at first. But he is soaking wet and silent, and he plays a haunting tune on his fiddle that chills Beet to the bone. Something is very, very wrong.

Things only get worse when Marina Shaw saunters into town and takes an unsettling interest in Gerry’s new baby. Local lore is filled with tales of a vicious shape-shifting sea creature and the cold, beautiful woman who controls him—a woman who bears a striking resemblance to Marina. Beet is determined to find out what happened to her beloved cousin, and to prevent the same fate from befalling the handsome new boy in town who is winning her heart, whether she wants him to or not. Yet the sea always exacts a price…

Preț: 51.09 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 77

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.78€ • 10.21$ • 8.09£

9.78€ • 10.21$ • 8.09£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Livrare express 28 februarie-06 martie pentru 18.40 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781534482456

ISBN-10: 1534482458

Pagini: 288

Ilustrații: f-c cvr (fx: foil stamp on soft touch); digital

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Atheneum Books for Young Readers

Colecția Atheneum Books for Young Readers

ISBN-10: 1534482458

Pagini: 288

Ilustrații: f-c cvr (fx: foil stamp on soft touch); digital

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Atheneum Books for Young Readers

Colecția Atheneum Books for Young Readers

Notă biografică

Regina M. Hansen was born on Prince Edward Island and grew up there, in Montreal, and in Boston. She teaches at Boston University and is also a contributor to The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Filmic Monsters. She has written regular articles for the nationally circulated children’s magazine DIG into History, and her essays have also appeared in The Wall Street Journal Review and The Conversation. The Coming Storm is her first novel. Visit her at ReginaMHansen.com.

Extras

Chapter One: Beet MacNeillCHAPTER ONE April 25, 1949 Beet MacNeill

I don’t know what wakes me up first—Mom shaking me, or the screaming.

My heart’s racing, even before I open my eyes. She’s standing above me, her hair coming out of its curlers and her pink chenille dressing gown buttoned up to the chin.

“Come on, Beet. Sit up, let’s go.” Mom’s talking a mile a minute, and her voice puts me in even more of a panic at first. Then I notice the look on her face. She’s not panicking, just glowering, like she always does when she’s on edge about something—and that right there’s enough to calm my heart back down. A little bit, anyway.

There’s a light on across the hall, and someone in there’s shrieking to scare the sin out of the Devil. I’m sitting up now, I can tell you, so quick I almost hit my head on the pail Mom’s holding out to me.

“That’s Deirdre! Is the baby…?”

Mom drops the pail into my lap. It’s made of aluminum and hurts like blazes when it lands. “The baby’s going to fall out onto the floor if I don’t get back in there. Now get a coat and go pump some water.”

The grandfather clock in the hall is striking five as I set my feet down on the cold wood floor and head downstairs. It’s not as frosty as it could be in April, but I’m still shivering like a dog in a wet blanket, or at least a dog in a yellow nightgown, which is what I’m wearing. Down in the kitchen, I grab Dad’s mackintosh off the peg by the oil stove, step into a pair of gum rubber boots and there’s Deirdre again, screamin’ to high Heaven and above it. I let the door bang behind me, thinking how I don’t ever want to have a baby, not if it hurts that bad. Especially not alone in some almost-stranger’s house, poor thing.

Deirdre’s my cousin Gerry Campbell’s girl, and notice I didn’t say wife. She’s been living with us since she found out for sure there was a baby coming, three days after Gerry left for the Boston States to fish cod off one of those Georges Bank trawlers—him, plus Joe Curley and Newmie Myers, with not a brain between the two of ’em. The boats go out for weeks at a time, and Gerry didn’t even know about the baby until last month. He was supposed to be earning the money for their wedding and for a house so that they wouldn’t have to depend on Mom and Dad, or worse, go live with Gerry’s not-so-poor widowed mother, Sarah (which would be a trial, let me tell you). Now Deirdre’s parents have put her out, and she’s staying here, in Gerry’s old room.

Gerry used to live with us when I was little. Sarah left him with Mom and Dad two weeks after she had him; abandoned him and ran off south with some man nobody ever saw. Came back for Gerry a year later, but even then, she was no sort of mother to him—always dressed up like your aunt’s spare room in her American catalogue clothes, while Gerry had to save his only shoes for school days. (At least that’s what Dad says.) Gerry ended up staying with us off and on his whole life while Sarah was out running the roads, taking long trips to Halifax, or Boston, all down the coast, even New York City one time. So he’s really more like my big brother than my cousin, especially since I never had any brothers and sisters of my own. Mom couldn’t because she had such a hard time having me. Says I’ve been giving her trouble since the day I was born, and she never lets me forget it.

Gerry took care of me a lot in those days. We used to go on all sorts of adventures, stuff Mom would have hated to know about. He’d bring me out on the boats, the salt air and the thrum of the sea like a kind of magic, filling me up. We’d go walking in the woods looking for rabbits and foxes, creeping as quiet as we could, hand in hand as we hoped for a glimpse of any small creature. Mostly Gerry took me to hear music. Wherever there was music playing, we were there drinking it in, figuring out how the tune went so we could try it later, on Gerry’s old fiddle. Sometimes we had to sit outside by the back door where the bootleggers came in, but I didn’t mind. It was worth it, being there with Gerry, hearing the music. Besides, Gerry kept me safe, and I kept him out of trouble.

I was even with him the first time he saw Deirdre (or at least the first time he saw her saw her, if you know what I mean, since everybody around here knows everybody else). It was a summer day when we went to the Legion Hall in Montague to hear Jimmy Arsenault’s band. We stopped at the new ice cream stand they have there, and Deirdre was sitting at one of the picnic tables in a yellow dress. Lorsh, did Gerry turn red, seeing her! Made me laugh to kill myself. He went right over to talk to her, though. Brave as brave, that’s our Gerry. She looked up and smiled at him, and that was that.

At first, Mom got right tight in the face about the baby, the scandal of it all, but Dad brought her round. I’m glad, too. Deirdre may not be blood family, but the baby will be. Gerry’s writing every week now since he’s back on shore in Boston, saying he’ll be home after the next trip out, with enough money for a family. Nobody in town believes him, except Deirdre, and me. I believe him. Gerry’s wild (I mean, Deirdre didn’t make that baby by herself, did she?), and he’s not the brightest in some ways, but he sure loves Deirdre. We went out looking for sea glass just before he left for Massachusetts, and he told me how much he loved her. I know he meant it, too. Gerry always tells me the truth. I can trust him, and I don’t trust just anybody.

There’s that terrible yell again. I speed up, the pail banging into my legs as I head for the pump. Poor Deirdre. The baby must be hurting her like crazy. She sure is brave, though, I’ve gotta say.

Our farm is a mile outside of Skinner Harbour, some few yards back from Nelson’s Point, a little knot of land looking out from Prince Edward Island across the Northumberland Strait. The pump is right by the back step, before Dad’s rosebushes. They’re bare now, but come June they’ll take up three long beds right down to the green wooden fence that protects them from the worst of the winds we get out here. Just thinking about how pretty they’ll be makes me believe I can smell them—above the dead seaweed smell of low tide, that is. Beyond the fence, through an iron gate, there’s a dusty clay path that leads down over the bank to our rocky beach and then to our fishing grounds, called the MacNeill Grounds on all the maps. That’s my name, Beatrice Mary MacNeill, but everyone calls me Beet for my red hair (and after my great-aunt Beet, who ran off to Bangor with a rumrunner).

The Strait’s flat calm today, and the air’s just as still as a funeral, which is good, because I’m cold enough without the wind. Across the water, I can see the shadow of Nova Scotia all rimmed in orange light. The sky’s pinking up, but there are still a few stars to be seen, all the more pretty for their being so dim. Soon they’ll wink out, disappear like magic, but there’s no time to stop and watch them. There’s a baby coming, a brand-new baby to live in my house! I can’t wait. I stoop down and hold the pail beneath the old iron pump, give the handle a push, then another, up and down until the water flows freely. That’s when I catch that whiff of roses again and see a sight that makes me drop the pail for joy. It’s joy at first, anyway.

Now, if you were to take that narrow dusty path beyond the gate down to the beach, and then walk south, in about a half a mile you’d reach Poxy Point, where the Campbells have their land. Gerry has been living back with his mother the last couple of years, taking care of her, running errands and things (just as if she deserved it, which she doesn’t). So he comes up that back path when he feels like a visit with us. Or he did, before he went off away. That could be why I don’t get startled when I look up to see Gerry walking toward me on that very path. Or why I don’t pay attention to that smell of roses that’s still rising up around me, growing stronger the nearer he gets. Instead I just leave the pail of water emptying at my feet and run toward him through the flowerbeds.

“Gerry!” I call out. “I can’t believe it. Deirdre’s just about to—” I stop short. “Hey, boy. You’re wet as a hen.”

We’ve both reached the gate at the same time, and Gerry’s just standing there, dripping, with his hair—red like mine—matted down over his freckled forehead. He’s wearing oilskins, the black pants fishermen wear aboard ship, and his green flannel shirt is spattered with blood and dirt. The queerest thing about it all is that he’s carrying his fiddle, the one Uncle Angus left him when he died. Gerry’s been using it to teach me lessons—or he was, anyway—every Saturday morning. (I’m aiming to be as good as Mrs. Thaddeus Mitchell, and she’s the best around, man or woman.)

Gerry hasn’t spoken yet. He just stares at me as he lifts the fiddle to his shoulder; draws the bow across it, slow as slow; and starts to play. At first it sounds like “Maiden’s Prayer,” sweet and lonely, but then the tune shifts to something older, with a strange rising and falling about it, coming from just beneath the melody. A shiver runs through me. The low, sad tune fills the air around me as two men appear on the bank behind Gerry. Like him, Joe Curley and Newmie Myers are soaking wet, ice-gray in the face, and solemn. There is a feeling growing in my chest, that cold, dark feeling I get on early winter mornings. I can’t seem to move.

As Joe and Newmie reach the fence, Gerry lowers the fiddle, and all three men stand still on the other side, looking at me with great hollow eyes. The air smells rotten-sweet, like flowers left too long in a vase. Now I know for sure what I should have guessed when I first smelled the roses out of season, what my heart knew before my head did, the moment I saw Gerry walking over the bank.

We stand there for a while just looking at one another as a gust of salt air lets me know the tide is turning, coming in. The cold, dark feeling is spreading through my whole self now. I feel my lip trembling like a little kid’s.

“Oh, Gerry,” I whisper, as tears fill my eyes. “Oh, no.”

He holds out his hand to me at the same time a new sound startles me—a cry higher pitched than Deirdre’s birthing yells, but just as loud. I turn my head toward the house, where a light still shines faintly in the upstairs window. It’s the baby I hear; the new baby is crying. When I turn back to the fence, Gerry and the other ghosts are gone.

I don’t know what wakes me up first—Mom shaking me, or the screaming.

My heart’s racing, even before I open my eyes. She’s standing above me, her hair coming out of its curlers and her pink chenille dressing gown buttoned up to the chin.

“Come on, Beet. Sit up, let’s go.” Mom’s talking a mile a minute, and her voice puts me in even more of a panic at first. Then I notice the look on her face. She’s not panicking, just glowering, like she always does when she’s on edge about something—and that right there’s enough to calm my heart back down. A little bit, anyway.

There’s a light on across the hall, and someone in there’s shrieking to scare the sin out of the Devil. I’m sitting up now, I can tell you, so quick I almost hit my head on the pail Mom’s holding out to me.

“That’s Deirdre! Is the baby…?”

Mom drops the pail into my lap. It’s made of aluminum and hurts like blazes when it lands. “The baby’s going to fall out onto the floor if I don’t get back in there. Now get a coat and go pump some water.”

The grandfather clock in the hall is striking five as I set my feet down on the cold wood floor and head downstairs. It’s not as frosty as it could be in April, but I’m still shivering like a dog in a wet blanket, or at least a dog in a yellow nightgown, which is what I’m wearing. Down in the kitchen, I grab Dad’s mackintosh off the peg by the oil stove, step into a pair of gum rubber boots and there’s Deirdre again, screamin’ to high Heaven and above it. I let the door bang behind me, thinking how I don’t ever want to have a baby, not if it hurts that bad. Especially not alone in some almost-stranger’s house, poor thing.

Deirdre’s my cousin Gerry Campbell’s girl, and notice I didn’t say wife. She’s been living with us since she found out for sure there was a baby coming, three days after Gerry left for the Boston States to fish cod off one of those Georges Bank trawlers—him, plus Joe Curley and Newmie Myers, with not a brain between the two of ’em. The boats go out for weeks at a time, and Gerry didn’t even know about the baby until last month. He was supposed to be earning the money for their wedding and for a house so that they wouldn’t have to depend on Mom and Dad, or worse, go live with Gerry’s not-so-poor widowed mother, Sarah (which would be a trial, let me tell you). Now Deirdre’s parents have put her out, and she’s staying here, in Gerry’s old room.

Gerry used to live with us when I was little. Sarah left him with Mom and Dad two weeks after she had him; abandoned him and ran off south with some man nobody ever saw. Came back for Gerry a year later, but even then, she was no sort of mother to him—always dressed up like your aunt’s spare room in her American catalogue clothes, while Gerry had to save his only shoes for school days. (At least that’s what Dad says.) Gerry ended up staying with us off and on his whole life while Sarah was out running the roads, taking long trips to Halifax, or Boston, all down the coast, even New York City one time. So he’s really more like my big brother than my cousin, especially since I never had any brothers and sisters of my own. Mom couldn’t because she had such a hard time having me. Says I’ve been giving her trouble since the day I was born, and she never lets me forget it.

Gerry took care of me a lot in those days. We used to go on all sorts of adventures, stuff Mom would have hated to know about. He’d bring me out on the boats, the salt air and the thrum of the sea like a kind of magic, filling me up. We’d go walking in the woods looking for rabbits and foxes, creeping as quiet as we could, hand in hand as we hoped for a glimpse of any small creature. Mostly Gerry took me to hear music. Wherever there was music playing, we were there drinking it in, figuring out how the tune went so we could try it later, on Gerry’s old fiddle. Sometimes we had to sit outside by the back door where the bootleggers came in, but I didn’t mind. It was worth it, being there with Gerry, hearing the music. Besides, Gerry kept me safe, and I kept him out of trouble.

I was even with him the first time he saw Deirdre (or at least the first time he saw her saw her, if you know what I mean, since everybody around here knows everybody else). It was a summer day when we went to the Legion Hall in Montague to hear Jimmy Arsenault’s band. We stopped at the new ice cream stand they have there, and Deirdre was sitting at one of the picnic tables in a yellow dress. Lorsh, did Gerry turn red, seeing her! Made me laugh to kill myself. He went right over to talk to her, though. Brave as brave, that’s our Gerry. She looked up and smiled at him, and that was that.

At first, Mom got right tight in the face about the baby, the scandal of it all, but Dad brought her round. I’m glad, too. Deirdre may not be blood family, but the baby will be. Gerry’s writing every week now since he’s back on shore in Boston, saying he’ll be home after the next trip out, with enough money for a family. Nobody in town believes him, except Deirdre, and me. I believe him. Gerry’s wild (I mean, Deirdre didn’t make that baby by herself, did she?), and he’s not the brightest in some ways, but he sure loves Deirdre. We went out looking for sea glass just before he left for Massachusetts, and he told me how much he loved her. I know he meant it, too. Gerry always tells me the truth. I can trust him, and I don’t trust just anybody.

There’s that terrible yell again. I speed up, the pail banging into my legs as I head for the pump. Poor Deirdre. The baby must be hurting her like crazy. She sure is brave, though, I’ve gotta say.

Our farm is a mile outside of Skinner Harbour, some few yards back from Nelson’s Point, a little knot of land looking out from Prince Edward Island across the Northumberland Strait. The pump is right by the back step, before Dad’s rosebushes. They’re bare now, but come June they’ll take up three long beds right down to the green wooden fence that protects them from the worst of the winds we get out here. Just thinking about how pretty they’ll be makes me believe I can smell them—above the dead seaweed smell of low tide, that is. Beyond the fence, through an iron gate, there’s a dusty clay path that leads down over the bank to our rocky beach and then to our fishing grounds, called the MacNeill Grounds on all the maps. That’s my name, Beatrice Mary MacNeill, but everyone calls me Beet for my red hair (and after my great-aunt Beet, who ran off to Bangor with a rumrunner).

The Strait’s flat calm today, and the air’s just as still as a funeral, which is good, because I’m cold enough without the wind. Across the water, I can see the shadow of Nova Scotia all rimmed in orange light. The sky’s pinking up, but there are still a few stars to be seen, all the more pretty for their being so dim. Soon they’ll wink out, disappear like magic, but there’s no time to stop and watch them. There’s a baby coming, a brand-new baby to live in my house! I can’t wait. I stoop down and hold the pail beneath the old iron pump, give the handle a push, then another, up and down until the water flows freely. That’s when I catch that whiff of roses again and see a sight that makes me drop the pail for joy. It’s joy at first, anyway.

Now, if you were to take that narrow dusty path beyond the gate down to the beach, and then walk south, in about a half a mile you’d reach Poxy Point, where the Campbells have their land. Gerry has been living back with his mother the last couple of years, taking care of her, running errands and things (just as if she deserved it, which she doesn’t). So he comes up that back path when he feels like a visit with us. Or he did, before he went off away. That could be why I don’t get startled when I look up to see Gerry walking toward me on that very path. Or why I don’t pay attention to that smell of roses that’s still rising up around me, growing stronger the nearer he gets. Instead I just leave the pail of water emptying at my feet and run toward him through the flowerbeds.

“Gerry!” I call out. “I can’t believe it. Deirdre’s just about to—” I stop short. “Hey, boy. You’re wet as a hen.”

We’ve both reached the gate at the same time, and Gerry’s just standing there, dripping, with his hair—red like mine—matted down over his freckled forehead. He’s wearing oilskins, the black pants fishermen wear aboard ship, and his green flannel shirt is spattered with blood and dirt. The queerest thing about it all is that he’s carrying his fiddle, the one Uncle Angus left him when he died. Gerry’s been using it to teach me lessons—or he was, anyway—every Saturday morning. (I’m aiming to be as good as Mrs. Thaddeus Mitchell, and she’s the best around, man or woman.)

Gerry hasn’t spoken yet. He just stares at me as he lifts the fiddle to his shoulder; draws the bow across it, slow as slow; and starts to play. At first it sounds like “Maiden’s Prayer,” sweet and lonely, but then the tune shifts to something older, with a strange rising and falling about it, coming from just beneath the melody. A shiver runs through me. The low, sad tune fills the air around me as two men appear on the bank behind Gerry. Like him, Joe Curley and Newmie Myers are soaking wet, ice-gray in the face, and solemn. There is a feeling growing in my chest, that cold, dark feeling I get on early winter mornings. I can’t seem to move.

As Joe and Newmie reach the fence, Gerry lowers the fiddle, and all three men stand still on the other side, looking at me with great hollow eyes. The air smells rotten-sweet, like flowers left too long in a vase. Now I know for sure what I should have guessed when I first smelled the roses out of season, what my heart knew before my head did, the moment I saw Gerry walking over the bank.

We stand there for a while just looking at one another as a gust of salt air lets me know the tide is turning, coming in. The cold, dark feeling is spreading through my whole self now. I feel my lip trembling like a little kid’s.

“Oh, Gerry,” I whisper, as tears fill my eyes. “Oh, no.”

He holds out his hand to me at the same time a new sound startles me—a cry higher pitched than Deirdre’s birthing yells, but just as loud. I turn my head toward the house, where a light still shines faintly in the upstairs window. It’s the baby I hear; the new baby is crying. When I turn back to the fence, Gerry and the other ghosts are gone.

Descriere

Music, myth, and horror blend in this romantic, atmospheric fantasy debut set on Prince Edward Island.