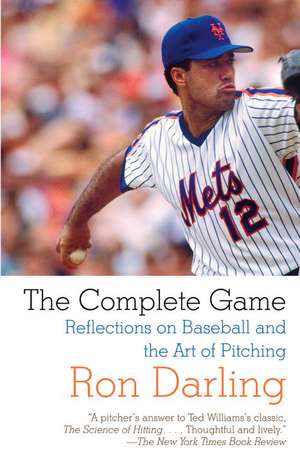

The Complete Game: Reflections on Baseball, Pitching, and Life on the Mound

Autor Ron Darling Daniel Paisneren Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2010

Preț: 104.66 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 157

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.03€ • 20.98$ • 16.56£

20.03€ • 20.98$ • 16.56£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 21 martie-04 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307390585

ISBN-10: 0307390586

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 136 x 201 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0307390586

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 136 x 201 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Ron Darling was a starting pitcher for the New York Mets from 1983 to 1991 and was the first Mets pitcher to be awarded a Gold Glove. Since 2006 he has been SportsNet New York’s game and studio analyst; since 2007 he has also been a game and studio analyst for TBS, for that network’s game-of-the-week and postseason broadcasts. Darling won an Emmy Award for best sports analyst in 2006. He was born in Honolulu, Hawaii, and attended Yale University, where he was a two-time All-American. He currently lives with his family in Manhattan.

Daniel Paisner has collaborated with dozens of athletes, actors, politicians, and business leaders on their autobiographies and memoirs. He is coauthor of Last Man Down: A Firefighter’s Story of Survival and Escape from the World Trade Center with FDNY battalion commander Richard Picciotto and The Girl in the Green Sweater: A Life in Holocaust’s Shadow with Krystyna Chiger.

Daniel Paisner has collaborated with dozens of athletes, actors, politicians, and business leaders on their autobiographies and memoirs. He is coauthor of Last Man Down: A Firefighter’s Story of Survival and Escape from the World Trade Center with FDNY battalion commander Richard Picciotto and The Girl in the Green Sweater: A Life in Holocaust’s Shadow with Krystyna Chiger.

Extras

Chapter 1

Pregame

Let’s Get It Right Today

Give me the damn ball!”

That’s been the rallying cry of major league pitchers since the turn of the last century. The ball. The pill. The rock. Call it what you want, it’s the only equipment we need—our badge of honor, our point of pride. It’s basic, as weapons go: a rounded piece of cushioned cork layered with a fine coating of rubber cement and wrapped in a tight winding of gray and tan wools and a thin poly-cotton thread. Then, another fine coating of rubber cement and two strips of cowhide, bound together with eighty-eight inches of waxed red thread— hand-sewn in the small farming village of Turrialba, Costa Rica, with 108 stitches.

But, of course, it’s not only about the ball. It’s about the act and art of throwing it, and the responsibility that goes with the privilege of doing so for a major league baseball team. For most of us who have taken the pitcher’s mound at the professional level, it’s the weight of carrying the fortunes of your teammates, the sweet burden of being on point, that sets our role apart. If we don’t execute, there’s no hiding it out there on that mound.

Everyone who plays a sport likes to think he or she is pivotal, but with pitchers this is not an arrogant or self-aggrandizing view. The game rests on our shoulders. We stand apart from our teammates and set the tone. All eyes are on us. The game is in our hands. The hopes of our teammates are pinned to our chest. Sure, the outcome of any one game might turn on a remarkable effort in the field, a mighty swing of the bat, a gutsy play on the bases, but everything that happens on a ball field—everything!—flows in some way through the pitcher. It has every damn thing to do with us. That’s how we feel, and the reason we feel this way is because it’s been drummed into us over countless starts, countless innings, countless pitches with the game on the line.

Tom Seaver, one of the greatest pitchers ever to take the mound, and certainly the greatest to do so in a New York Mets uniform, had a cutting way with words. If he liked you, he was one of the most generous souls in the game. If he didn’t ... well, not so much. We played together, briefly, in 1983, when I joined the big club for a late-season cameo. It was Tom’s second tour with the Mets, and he was cast as a conquering hero, a favorite son turned elder statesman. He had a not-so-flattering nickname for the Mets trainer, “Fifty-Fifty”; I couldn’t figure why. After I’d been in the bigs for a couple weeks, I got up the courage to ask Tom how he came up with the name.

“He’s not the best trainer, kid,” said Tom, who himself was known as “the Franchise.” (How’s that for a nickname to confirm my point?) “And he’s not the worst. He doesn’t help you, he doesn’t hurt you. Fifty-Fifty.”

I’ve thought about that moniker a lot over the years, and early on I hoped it never applied to me as a ballplayer, affectionately or otherwise. Over time, however, I realized there was no avoiding the tag. Sometimes you justify the faith your teammates place in you, and sometimes you don’t. If you come through more often than not, you’re doing okay. And yet, in success and in struggle, getting the ball on game day has to be the greatest rush in professional sports. The game acknowledges this, in its own way. There’s a certain amount of ceremony to the “anointing” or assigning of pitching duties, like a transfer of power. It used to be that pitchers knew they were getting a start only when they arrived at their locker to find that day’s pristine game ball sitting in their glove. The first time I heard about that, I was already in the bigs, and it struck me as a fitting tradition: you come to the ballpark; you find the ball in your locker; you understand it’s on you. That particular baseball ritual is gone, but the symbolism holds. You can see it in the way an entire team stands back in deference to the particulars of its starting pitcher. You can see it in the stony silence position players offer their pitcher while he’s throwing a gem—or a dud. You can see it in the way a manager waits on the mound to place the ball in the hands of a reliever after a pitching change. He strips one pitcher of the honor and delivers it to the next, sending one man to the showers while his successor takes the hill. The sword is passed, and we’re entrusted with the fate of our franchise—for that one day, or even that one batter, at least until we fall short.

A starting pitcher, on his day, is a man alone. You’re totally ignored by your teammates. You feel it the moment you get to the ballpark, and it runs through the entire game. There are exceptions: some pitchers are nervous and like to kid around, to relax; some pitchers reach out to their teammates and engage them in conversation, about the game or something else. But most pitchers are off on their own, lost in thought, making ready. They’re looking for that zone, that tunnel, that place of calm and quiet that lets them get their head around the game, while their teammates hang back warily, afraid to encroach.

It’s a special, certain thrill to head out to the ballpark knowing the game is yours, to do with what you will. For my family, it was somewhat less thrilling. I’d get a little moody as game day approached. On the morning of a game, it’s possible I even lapsed into surliness. I was something of a bear, I was told, and my game- day habits reflected this. I would not be crossed or told what to do. For night games, I took my lunch at noon, because I wanted to be good and hungry and in an even fouler mood when game time rolled around. Lunch was always the same: steak, mashed potatoes, and peas. (Note: try finding good peas in Cincinnati.) All day long, I drank plenty of water—more or less, depending on the weather. (Another note: there wasn’t enough water on the planet to keep a pitcher hydrated on the St. Louis turf, middle of August, when temperatures ran to 130 degrees.) There was also a touch of cold sweats and nausea.

Game days at Shea were a particular adventure. On the road, I could hide in the shadows of the team bus, but at home I was on my own. You’d never know what might set me off. Early on in my career, I was the guy you didn’t want to talk to on the 7 train out to Flushing—not quite De Niro in Taxi Driver, but close. Later, when the fans started to recognize me and the subway was no longer an option, I was the guy you didn’t want to piss off on the Grand Central Parkway—the guy who could claim road rage as an essential occupational tool.

Leave me alone. That’s the message I put out to the world on days I was due to pitch. Even to my wife and kids, the message was much the same: leave me alone so I can do my thing and prepare for battle.

People who know me will tell you I’m basically a good person. I’m kind to animals, and kids, and little old ladies. I hold the door open for strangers. But on game day, I was someone else, someone I didn’t recognize—someone I didn’t even necessarily like. Understand, I didn’t will myself into a sour, angry mood; it just happened, and it happened for a reason. I was on a knife edge. It all fell to me— that’s how I approached my time on the mound, and that approach inevitably colored my personality. I imagined I was a boxer, getting ready to step into the ring. A matador preparing to face down a charging bull. A fighter pilot embarking on a do-or-die mission.

God help the poor manager or pitching coach who had to administer last-minute instructions. Mel Stottlemyre, the Mets pitching coach and great father figure to all of us young pitchers on those talented Mets teams of the late 1980s, knew how to handle me on game days. He was careful not to set me off, but at the same time there were always a couple things he felt he needed to discuss. I rarely bit Mel’s head off, but I don’t think I ever really listened to him, either. Despite his best efforts, I never could pay attention. Between starts, sure, I let Mel have his say, and I valued his input. He made me a better pitcher. But just before a start, I didn’t want to hear it. I couldn’t hear it.

Keeping up with Mel and his final analysis was like trying to read the phone book. I couldn’t focus on it. Nothing against Mel, but my mind was always someplace else. I was impatient. I hadn’t eaten. I’d angered or frustrated or otherwise alienated every poor soul who had crossed my path on the way to the stadium. I was pumped and primed. I needed a baseball in my hands. Enough already with the pregame discussions, I always thought. Enough with the nerves and the nausea. I was a bundle of raw energy, held together by one pleading thought: Just give me the damn ball. Please.

It wasn’t until I was out in the bullpen going through my pregame warm-up that my pitching brain would click on. I’d ease into my first couple throws, soft tosses to the bullpen catcher, first from thirty or forty feet away, then fifty, and finally from the full pitching distance of sixty feet and six inches. Just a mindless game of catch, the kind I played on a thousand lazy afternoons as a kid, until I forced myself to pay attention to how my arm was feeling. There was no need for any more talk. Was I getting loose or was I in trouble? That’s all that mattered here in the bullpen. Was I ready? Was I on? I’d be acutely aware of every muscle in my body, every ache and pain, every tic and twitch. I could see and feel everything, and underneath the mindlessness of the routine I’d find time to consider every game- day variable: who was catching me, who was playing behind me in the field, who’d given me trouble in the opposing lineup, what I planned to eat for dinner that night, the weather.

The pitching coach would stand watch. When it was Mel, he’d be motionless and quiet, until the throwing grew more intense. After that, he still didn’t say anything, but I could see from the corner of my eye that he was paying careful attention. In just a few minutes, the manager would call down to ask how I was throwing. God bless Mel. I know he must have lied to Davey Johnson on a number of occasions—but there were even more occasions when he didn’t have to lie. When my arm felt great. When I finished strong, hitting my spots, making the ball do whatever I wanted. When I felt invincible.

The warm-up over, I’d begin that long, purposeful walk back to the dugout. The walk out to the bullpen may have been slow, but this return trip always had a little more urgency to it. I’d sidle past my bullpen brethren, accepting their claps on the back and their go- get-’ems like I had them coming. (None would admit it, but I’m sure a few of those well-wishers were imploring me to do well so they wouldn’t be called on to pitch me out of a jam.) I’d make my way through the bowels of the stadium, my cleats clicking against the cement floor like Morse code, the message a warning to the other team that I was really bringing it or a signal to my own guys to be on their toes. Mel would usually attempt a joke, to ease the tension, but I never thought the tension needed easing. I wanted to be on edge in order to do what I had to do. The security guards would shout out words of encouragement as I passed. (Half of them were Yankee fans, but what the hell.) On to the family room, where the next-of-Met-kin waited out the long stretch between warm-up and first pitch, and I’d chide myself for not knowing the names of my teammates’ wives and children.

As I moved toward the mound—my office! my haven!—a voice switched on in my head, guiding me the rest of the way: No left turn into the clubhouse, you coward. Continue on. And I would, over the makeshift catwalk of AstroTurf remnants leading down the stairs to the dugout. At the bottom of the stairs, I’d find the other eight starting players, hastily sucking the last drags from their cigarettes. (Sorry, kids, but the players smoked in those days.) I’d ignore their initial looks of Shit, I can’t believe he’s here already and register instead their follow-up looks of C’mon, Ronnie, we need this one tonight. I’d walk past the boys and up the five short steps into the Mets dugout. At the other end, I’d spot Mel talking to the manager. I’d hope he didn’t have to lie tonight. I’d tell myself I felt pretty good, and then I’d take my seat on the dugout bench and towel off.

This was always the most peaceful time of my pregame ritual. It didn’t last all that long, but I would try to lose myself in that brief moment. I’d think back to what baseball had meant to me as a kid. To all those hours playing with my brothers, my friends, my parents. To how lucky I was to wear a major league uniform. To be pitching, in just a few short moments, in front of fifty thousand fans.

Soon the other starting players would join me on the bench, awaiting their cue to take the field. That cue doesn’t come from the public address announcer. It doesn’t come from one of the coaches or the umpire. It comes from the starting pitcher. Remember, it starts with us, and it ends with us. Every starting pitcher has his own cue, some version of the “Give me the damn ball!” rallying cry that opened these pages. Dwight Gooden, with his eerily quiet confidence, used to nod his head ever so slightly, as if to say, “Let’s go!” Sid Fernandez would humbly shrug his burly Hawaiian shoulders and offer a look: Hey, you want to go?

From the Hardcover edition.

Pregame

Let’s Get It Right Today

Give me the damn ball!”

That’s been the rallying cry of major league pitchers since the turn of the last century. The ball. The pill. The rock. Call it what you want, it’s the only equipment we need—our badge of honor, our point of pride. It’s basic, as weapons go: a rounded piece of cushioned cork layered with a fine coating of rubber cement and wrapped in a tight winding of gray and tan wools and a thin poly-cotton thread. Then, another fine coating of rubber cement and two strips of cowhide, bound together with eighty-eight inches of waxed red thread— hand-sewn in the small farming village of Turrialba, Costa Rica, with 108 stitches.

But, of course, it’s not only about the ball. It’s about the act and art of throwing it, and the responsibility that goes with the privilege of doing so for a major league baseball team. For most of us who have taken the pitcher’s mound at the professional level, it’s the weight of carrying the fortunes of your teammates, the sweet burden of being on point, that sets our role apart. If we don’t execute, there’s no hiding it out there on that mound.

Everyone who plays a sport likes to think he or she is pivotal, but with pitchers this is not an arrogant or self-aggrandizing view. The game rests on our shoulders. We stand apart from our teammates and set the tone. All eyes are on us. The game is in our hands. The hopes of our teammates are pinned to our chest. Sure, the outcome of any one game might turn on a remarkable effort in the field, a mighty swing of the bat, a gutsy play on the bases, but everything that happens on a ball field—everything!—flows in some way through the pitcher. It has every damn thing to do with us. That’s how we feel, and the reason we feel this way is because it’s been drummed into us over countless starts, countless innings, countless pitches with the game on the line.

Tom Seaver, one of the greatest pitchers ever to take the mound, and certainly the greatest to do so in a New York Mets uniform, had a cutting way with words. If he liked you, he was one of the most generous souls in the game. If he didn’t ... well, not so much. We played together, briefly, in 1983, when I joined the big club for a late-season cameo. It was Tom’s second tour with the Mets, and he was cast as a conquering hero, a favorite son turned elder statesman. He had a not-so-flattering nickname for the Mets trainer, “Fifty-Fifty”; I couldn’t figure why. After I’d been in the bigs for a couple weeks, I got up the courage to ask Tom how he came up with the name.

“He’s not the best trainer, kid,” said Tom, who himself was known as “the Franchise.” (How’s that for a nickname to confirm my point?) “And he’s not the worst. He doesn’t help you, he doesn’t hurt you. Fifty-Fifty.”

I’ve thought about that moniker a lot over the years, and early on I hoped it never applied to me as a ballplayer, affectionately or otherwise. Over time, however, I realized there was no avoiding the tag. Sometimes you justify the faith your teammates place in you, and sometimes you don’t. If you come through more often than not, you’re doing okay. And yet, in success and in struggle, getting the ball on game day has to be the greatest rush in professional sports. The game acknowledges this, in its own way. There’s a certain amount of ceremony to the “anointing” or assigning of pitching duties, like a transfer of power. It used to be that pitchers knew they were getting a start only when they arrived at their locker to find that day’s pristine game ball sitting in their glove. The first time I heard about that, I was already in the bigs, and it struck me as a fitting tradition: you come to the ballpark; you find the ball in your locker; you understand it’s on you. That particular baseball ritual is gone, but the symbolism holds. You can see it in the way an entire team stands back in deference to the particulars of its starting pitcher. You can see it in the stony silence position players offer their pitcher while he’s throwing a gem—or a dud. You can see it in the way a manager waits on the mound to place the ball in the hands of a reliever after a pitching change. He strips one pitcher of the honor and delivers it to the next, sending one man to the showers while his successor takes the hill. The sword is passed, and we’re entrusted with the fate of our franchise—for that one day, or even that one batter, at least until we fall short.

A starting pitcher, on his day, is a man alone. You’re totally ignored by your teammates. You feel it the moment you get to the ballpark, and it runs through the entire game. There are exceptions: some pitchers are nervous and like to kid around, to relax; some pitchers reach out to their teammates and engage them in conversation, about the game or something else. But most pitchers are off on their own, lost in thought, making ready. They’re looking for that zone, that tunnel, that place of calm and quiet that lets them get their head around the game, while their teammates hang back warily, afraid to encroach.

It’s a special, certain thrill to head out to the ballpark knowing the game is yours, to do with what you will. For my family, it was somewhat less thrilling. I’d get a little moody as game day approached. On the morning of a game, it’s possible I even lapsed into surliness. I was something of a bear, I was told, and my game- day habits reflected this. I would not be crossed or told what to do. For night games, I took my lunch at noon, because I wanted to be good and hungry and in an even fouler mood when game time rolled around. Lunch was always the same: steak, mashed potatoes, and peas. (Note: try finding good peas in Cincinnati.) All day long, I drank plenty of water—more or less, depending on the weather. (Another note: there wasn’t enough water on the planet to keep a pitcher hydrated on the St. Louis turf, middle of August, when temperatures ran to 130 degrees.) There was also a touch of cold sweats and nausea.

Game days at Shea were a particular adventure. On the road, I could hide in the shadows of the team bus, but at home I was on my own. You’d never know what might set me off. Early on in my career, I was the guy you didn’t want to talk to on the 7 train out to Flushing—not quite De Niro in Taxi Driver, but close. Later, when the fans started to recognize me and the subway was no longer an option, I was the guy you didn’t want to piss off on the Grand Central Parkway—the guy who could claim road rage as an essential occupational tool.

Leave me alone. That’s the message I put out to the world on days I was due to pitch. Even to my wife and kids, the message was much the same: leave me alone so I can do my thing and prepare for battle.

People who know me will tell you I’m basically a good person. I’m kind to animals, and kids, and little old ladies. I hold the door open for strangers. But on game day, I was someone else, someone I didn’t recognize—someone I didn’t even necessarily like. Understand, I didn’t will myself into a sour, angry mood; it just happened, and it happened for a reason. I was on a knife edge. It all fell to me— that’s how I approached my time on the mound, and that approach inevitably colored my personality. I imagined I was a boxer, getting ready to step into the ring. A matador preparing to face down a charging bull. A fighter pilot embarking on a do-or-die mission.

God help the poor manager or pitching coach who had to administer last-minute instructions. Mel Stottlemyre, the Mets pitching coach and great father figure to all of us young pitchers on those talented Mets teams of the late 1980s, knew how to handle me on game days. He was careful not to set me off, but at the same time there were always a couple things he felt he needed to discuss. I rarely bit Mel’s head off, but I don’t think I ever really listened to him, either. Despite his best efforts, I never could pay attention. Between starts, sure, I let Mel have his say, and I valued his input. He made me a better pitcher. But just before a start, I didn’t want to hear it. I couldn’t hear it.

Keeping up with Mel and his final analysis was like trying to read the phone book. I couldn’t focus on it. Nothing against Mel, but my mind was always someplace else. I was impatient. I hadn’t eaten. I’d angered or frustrated or otherwise alienated every poor soul who had crossed my path on the way to the stadium. I was pumped and primed. I needed a baseball in my hands. Enough already with the pregame discussions, I always thought. Enough with the nerves and the nausea. I was a bundle of raw energy, held together by one pleading thought: Just give me the damn ball. Please.

It wasn’t until I was out in the bullpen going through my pregame warm-up that my pitching brain would click on. I’d ease into my first couple throws, soft tosses to the bullpen catcher, first from thirty or forty feet away, then fifty, and finally from the full pitching distance of sixty feet and six inches. Just a mindless game of catch, the kind I played on a thousand lazy afternoons as a kid, until I forced myself to pay attention to how my arm was feeling. There was no need for any more talk. Was I getting loose or was I in trouble? That’s all that mattered here in the bullpen. Was I ready? Was I on? I’d be acutely aware of every muscle in my body, every ache and pain, every tic and twitch. I could see and feel everything, and underneath the mindlessness of the routine I’d find time to consider every game- day variable: who was catching me, who was playing behind me in the field, who’d given me trouble in the opposing lineup, what I planned to eat for dinner that night, the weather.

The pitching coach would stand watch. When it was Mel, he’d be motionless and quiet, until the throwing grew more intense. After that, he still didn’t say anything, but I could see from the corner of my eye that he was paying careful attention. In just a few minutes, the manager would call down to ask how I was throwing. God bless Mel. I know he must have lied to Davey Johnson on a number of occasions—but there were even more occasions when he didn’t have to lie. When my arm felt great. When I finished strong, hitting my spots, making the ball do whatever I wanted. When I felt invincible.

The warm-up over, I’d begin that long, purposeful walk back to the dugout. The walk out to the bullpen may have been slow, but this return trip always had a little more urgency to it. I’d sidle past my bullpen brethren, accepting their claps on the back and their go- get-’ems like I had them coming. (None would admit it, but I’m sure a few of those well-wishers were imploring me to do well so they wouldn’t be called on to pitch me out of a jam.) I’d make my way through the bowels of the stadium, my cleats clicking against the cement floor like Morse code, the message a warning to the other team that I was really bringing it or a signal to my own guys to be on their toes. Mel would usually attempt a joke, to ease the tension, but I never thought the tension needed easing. I wanted to be on edge in order to do what I had to do. The security guards would shout out words of encouragement as I passed. (Half of them were Yankee fans, but what the hell.) On to the family room, where the next-of-Met-kin waited out the long stretch between warm-up and first pitch, and I’d chide myself for not knowing the names of my teammates’ wives and children.

As I moved toward the mound—my office! my haven!—a voice switched on in my head, guiding me the rest of the way: No left turn into the clubhouse, you coward. Continue on. And I would, over the makeshift catwalk of AstroTurf remnants leading down the stairs to the dugout. At the bottom of the stairs, I’d find the other eight starting players, hastily sucking the last drags from their cigarettes. (Sorry, kids, but the players smoked in those days.) I’d ignore their initial looks of Shit, I can’t believe he’s here already and register instead their follow-up looks of C’mon, Ronnie, we need this one tonight. I’d walk past the boys and up the five short steps into the Mets dugout. At the other end, I’d spot Mel talking to the manager. I’d hope he didn’t have to lie tonight. I’d tell myself I felt pretty good, and then I’d take my seat on the dugout bench and towel off.

This was always the most peaceful time of my pregame ritual. It didn’t last all that long, but I would try to lose myself in that brief moment. I’d think back to what baseball had meant to me as a kid. To all those hours playing with my brothers, my friends, my parents. To how lucky I was to wear a major league uniform. To be pitching, in just a few short moments, in front of fifty thousand fans.

Soon the other starting players would join me on the bench, awaiting their cue to take the field. That cue doesn’t come from the public address announcer. It doesn’t come from one of the coaches or the umpire. It comes from the starting pitcher. Remember, it starts with us, and it ends with us. Every starting pitcher has his own cue, some version of the “Give me the damn ball!” rallying cry that opened these pages. Dwight Gooden, with his eerily quiet confidence, used to nod his head ever so slightly, as if to say, “Let’s go!” Sid Fernandez would humbly shrug his burly Hawaiian shoulders and offer a look: Hey, you want to go?

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“A pitcher’s answer to Ted Williams’s classic, The Science of Hitting. . . . Thoughtful and lively. . . . [Darling is] an affable, frank and witty guide.”

—Bruce Handy, The New York Times Book Review

“[Darling] writes soulfully about coming into and leaving the game. . . . When most former major leaguers write memoirs, you wonder why they bothered; with Ron Darling . . . you wonder why it took him so long.”

—Newsday

“Incisive, in-depth. . . . The antithesis of the sordid baseball tell-all. . . . Darling’s pitch-by-pitch descriptions . . . illustrate the complexity of baseball. . . . Fascinating. . . . [Darling] seems to have an almost photographic memory of every game he pitched.”

—Pittsburgh Tribune-Review

“[Darling] can explain all the cerebral stuff while also answering some questions fans always wonder about. . . . It’s a snapshot inside a pitcher’s head, and for a baseball fan, it’s worth framing. . . . An unconventional baseball book. . . . A very good one, too.”

—New York Daily News

“An insightful story for anyone who loves the game.”

—Minneapolis Star Tribune

“Darling comes up a winner in his rookie writing effort. There’s plenty to satisfy Met fans—and more. . . . In his typically engaging style, [Darling] lets the reader in on the parts of the game fans can't see from the stands or on their TVs.”

—The New York Post

“[Darling’s] recall is 20/20, his reflections revealing for anyone interested in a true inside view of his sport. . . . This is a book for the curious and the purist, full of anecdotes but always focused.”

—The Toronto Star

“Darling offers pitches and outcomes . . . from ten selected games in his career. . . . Among them are enough oddities and thrilling turns of baseball to make a reader glad to be here and–well, not out there.”

—The New Yorker

“Mets fans already know Ron Darling as one of the game’s most insightful commentators, but this is a book for all of Baseball Nation to cherish. Just as artfully as he once changed speeds, Darling moves adeptly between his own experience on the mound and his probing analysis of the art and psychology of pitching to offer us a rare glimpse inside the world of the loneliest man on the field. The result is the pitching equivalent of Ted Williams’ The Science of Hitting.”

—Jonathan Mahler, author of Ladies and Gentlemen, the Bronx is Burning

“It’s hard to recall a baseball book that offers as much information about the game—from a player’s perspective—as this one.”

—Booklist

“Darling’s little gem of a book immediately takes its place alongside Ball Four and Moneyball as a classic, and the best account ever of the way pitchers think.”

—Joseph J. Ellis, author of American Creation

“Totally absorbing. Ron Darling takes us inside the mind of a pitcher, and a funny, thoughtful, and observant one at that.”

—Kevin Baker, author of Sometimes You See it Coming and Paradise Alley

—Bruce Handy, The New York Times Book Review

“[Darling] writes soulfully about coming into and leaving the game. . . . When most former major leaguers write memoirs, you wonder why they bothered; with Ron Darling . . . you wonder why it took him so long.”

—Newsday

“Incisive, in-depth. . . . The antithesis of the sordid baseball tell-all. . . . Darling’s pitch-by-pitch descriptions . . . illustrate the complexity of baseball. . . . Fascinating. . . . [Darling] seems to have an almost photographic memory of every game he pitched.”

—Pittsburgh Tribune-Review

“[Darling] can explain all the cerebral stuff while also answering some questions fans always wonder about. . . . It’s a snapshot inside a pitcher’s head, and for a baseball fan, it’s worth framing. . . . An unconventional baseball book. . . . A very good one, too.”

—New York Daily News

“An insightful story for anyone who loves the game.”

—Minneapolis Star Tribune

“Darling comes up a winner in his rookie writing effort. There’s plenty to satisfy Met fans—and more. . . . In his typically engaging style, [Darling] lets the reader in on the parts of the game fans can't see from the stands or on their TVs.”

—The New York Post

“[Darling’s] recall is 20/20, his reflections revealing for anyone interested in a true inside view of his sport. . . . This is a book for the curious and the purist, full of anecdotes but always focused.”

—The Toronto Star

“Darling offers pitches and outcomes . . . from ten selected games in his career. . . . Among them are enough oddities and thrilling turns of baseball to make a reader glad to be here and–well, not out there.”

—The New Yorker

“Mets fans already know Ron Darling as one of the game’s most insightful commentators, but this is a book for all of Baseball Nation to cherish. Just as artfully as he once changed speeds, Darling moves adeptly between his own experience on the mound and his probing analysis of the art and psychology of pitching to offer us a rare glimpse inside the world of the loneliest man on the field. The result is the pitching equivalent of Ted Williams’ The Science of Hitting.”

—Jonathan Mahler, author of Ladies and Gentlemen, the Bronx is Burning

“It’s hard to recall a baseball book that offers as much information about the game—from a player’s perspective—as this one.”

—Booklist

“Darling’s little gem of a book immediately takes its place alongside Ball Four and Moneyball as a classic, and the best account ever of the way pitchers think.”

—Joseph J. Ellis, author of American Creation

“Totally absorbing. Ron Darling takes us inside the mind of a pitcher, and a funny, thoughtful, and observant one at that.”

—Kevin Baker, author of Sometimes You See it Coming and Paradise Alley

Descriere

Darling, who helped the Mets win the 1986 World Series, is considered one of the most articulate and insightful broadcasters in baseball. Now, he presents an engaging, practical, and philosophical exploration of the art, strategy, and psychology of pitching.