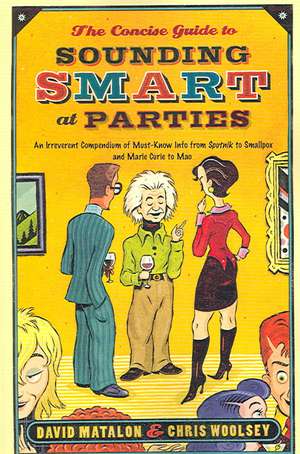

The Concise Guide to Sounding Smart at Parties: An Irreverent Compendium of Must-Know Info from Sputnik to Smallpox and Mao to Marie Curie

Autor David Matalon, Chris Woolseyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2006

We’ve all been there. You’re at a party, surrounded by the most important people in your life. You’re cool. You’re casual. You’re witty and urbane. Until suddenly, quite unexpectedly, things take a turn for the worse when a subject thought to be common knowledge is lobbed your way. A hush falls over the room and every head seems to swivel expectantly in your direction.

[ART: SET THESE OFF IN A DIFFERENT COLOR?]

“Rasputin. Sure, Rasputin. The Russian guy, right? Who . . . who . . . whooooo was Russian.”

“Che Guevara? You mean the dancer?”

“Oh my God! Mao Tse-tung? They have the best chicken with cashews!”

The Concise Guide to Sounding Smart at Parties was written with just this moment in mind. In fourteen pain-free, laughter-filled chapters, authors David Matalon and Chris Woolsey brush away years of cobwebs on subjects as wide-ranging as the typical round of Jeopardy: war, science, politics, philosophy, the arts, business, literature, music, religion, and more.

Armed with The Concise Guide to Sounding Smart at Parties, you’ll know that Chicago Seven wasn’t a boy band, Martin Luther never fought for civil rights, and Franz Kafka isn’t German for “I have a bad cold.” You’ll be the smart one who’s the center of conversation—and nothing beats that feeling.

Preț: 107.92 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 162

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.65€ • 21.56$ • 17.05£

20.65€ • 21.56$ • 17.05£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767922999

ISBN-10: 0767922999

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767922999

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

DAVID MATALON is a film and TV screenwriter and is directing his first feature film in Los Angeles. CHRIS WOOLSEY is a freelance writer who has worked for Sony Pictures and Columbia Tri-Star. Chris also tours the country as a youth speaker.

Extras

• 1 •

The War Conversation

The sadly useful thing about the war conversation is that there’s always some kind of bloodshed going on somewhere in the world, and so it's easy to bring up. Though military history has been traditionally a guy topic, these days it's quite likely that in a room full of people of either sex someone will have served or at least had a sibling, significant other, or “ex” who did. Certainly, if you’re attending any armed forces related affair, familiarizing yourself with a few topics in the war conversation will help you win friends and get people talking. However, be mindful that you are likely to find a handful of Experts (see the Appendix, Who’s Who at the Party) in the crowd who will give you a run for your military money. So once things are rolling, consider where to take the talk next. Generally, military buffs tend to like video games, sports, action flicks (war movies), and politics. It’s worth noting, if you're dealing with people in the actual military, it’s a good rule of thumb to stay clear of criticizing the government, unless you get the sense that the people you’re dealing with have liberal, or at the very least, tolerant views.

Hannibal Was Republic Enemy Number One

When Are We Talking About: 247 BC-183 BC

Why Are We Even Talking About This: Hannibal was one of the most famous military commanders in history, who impossibly led his army (including cavalry and elephants), across the Swiss Alps into the heart of the Roman Empire, not only surprising the Roman legions but nearly destroying them.

What You Need to Know to Sound Smart: Hannibal Barca was born in Carthage (near modern-day Tunis), North Africa, in 247 BC, the son of Hamilcar (boy, they sure had great names in Carthage, didn't they?), the general who defended Sicily against the Romans in the First Punic War (nothing like the Pubic War waged by penis enlargement companies on the Internet). While most dads teach their boys to play baseball and fish, Hamilcar despised the Roman Empire and kindled the same hatred in Hannibal. With training-spear in hand, ten-year-old Hannibal traveled with his father to war in Spain, and by age twenty-six was a general, replacing his dead brother-in-law, Hasdrubal (a name ripe for telemarketer screwups: “Is Mr. Haysdrooble in? Well, is Mrs. Haysdrooble there?”) In 223 BC, Hannibal attacked and conquered Saguntum, modern-day Sagunto (wherever the hell that is…just kidding, it's in Spain), and won the support of his native city, thus laying the foundation for what would become the Second Punic War (218-201 BC).

Fed up with Roman imperialism (he preferred his own), Hannibal decided to surprise the Roman army by taking the fight to them. In a daring and nearly suicidal move, Hannibal led his Carthaginian army, including baggage train (that is, food supplies, not that blind date you had who unloaded all of his problems on you the first time you got together for tuna rolls), on foot across the Alps, a total of 1,500 miles with not a freeway or HoJo’s in sight. Hannibal appeared unexpectedly in Northern Italy and fell upon the undefended Po Valley (218-217 BC), catching the Roman soldiers with their togas down around their ankles.

As word of Hannibal’s victories spread, new recruits from Rome’s other enemies (like everyone in civilization) flocked to his banner, following Hannibal as he defeated several Roman armies (mind you, the mightiest military force in the world at that time), sometimes while outnumbered four to one. At the famed Battle of Cannae, Hannibal brilliantly used his cavalry to outflank the Romans, who had twice as many soldiers, and destroyed their army to a man. (His name was Frederico and he was a snappy dresser.) Between 25,000 and 50,000 Romans were slain and 10,000 captured, compared to Hannibal's 5,700, of which the vast majority were Celts and Iberians (Spanish).

With this great victory, Southern Italy rose up against the empire, joining Hannibal, as he threatened to end the power of Rome a few centuries earlier than scheduled. However, internal squabbles from the nimrods back in Carthage resulted in the loss of financial support, and Hannibal was left to survive on traveler's checks. (“Hey, guys, just like twenty more bucks and I could finish this.”) Hannibal refused to go home, and instead hung out in Italy, touring the cities with his army, sacking wherever he went if his rigatoni wasn’t al dente and crushing any who dared to face him, until Roman generals were too afraid to take the field (imagine if Mexicans invaded Texas and took over the entire southern half of the state and the U.S. government was helpless to stop them … well, just imagine Texas). Hannibal was at last recalled to defend his home city against a young Roman commander, Scipio Africanus, who at the Battle of Zama (Africa), finally conquered the Carthaginian commander.

Hannibal retired from military life in 200 BC, but four years later, began to publicly lash out at his city’s corrupt aristocracy. The powers that be, fearing Hannibal's influence, sold him out to the Romans (who still had a Punic bone to pick with him for rubbing their noses in the elephant poo he left all over their country) by falsely accusing him of plotting another attack on Rome. In an incredible strategic blunder, Hannibal launched a surprise assault against the Empire (“They think I'm gonna attack, but what they don’t know is … I'm gonna attack!”). But as we said, the Romans did know and had a massive welcome back party waiting. Consequently, Hannibal was forced to retreat to Asia Minor in 183 BC, where the Romans pressured the local ruler, Prusias I, for his surrender (“If you give us Hannibal, we’ll give you working toilets. Whaddya say?”). Trapped and out of options, rather than give in to his lifelong enemy, Hannibal poisoned himself in Libyssa, Turkey. Death by street kebab, what a way to go.

Interesting Tidbit: When his son was just nine years old, before departing on the Spanish campaign, Hamilcar took Hannibal to the altar and made him repeat this oath, “I swear that so soon as age will permit, I will use fire and steel to arrest the destiny of Rome.” Hatred truly does begin in the home.

Ways to Bring Up Hannibal in Conversation

• There’s more foreigners here than in Hannibal's army.

• That guy is the Hannibal of my existence, always popping up unexpectedly and making my life miserable.

• I’m having a Hannibal day. I feel like I’m winning the battle, but losing the war.

Saladin Won the Noble Prize During the Crusades

When Are We Talking About: 1138-1193

Why Are We Even Talking About This: Saladin was the notoriously fair and chivalrous sultan of Egypt and the greatest general to face the European crusaders. He conquered Jerusalem and restored Sunnism to Egypt and Syria.

What You Need to Know to Sound Smart: Salah ad-Din Yusuf Ibn Ayyub (or Saladin, to anyone living west of the Nile) was born in Tikrit, Mesopotamia, around 1138, to a wealthy Kurdish family in northern Iraq (you know, the people from the old “no fly zone”), but grew up in the court of Nur ad–Din, the ruler of Syria, the caliph of Damascus, kind of like a state governor but with camels. In the court, he studied the Koran, philosophy, the Koran, military history, the Koran, the Koran, poetry and followed that up with a little bedtime Koran. At age fourteen, when most young boys are mastering Halo2, Saladin (meaning Righteous of the Faith) joined his uncle Shirkuh’s military staff on a campaign into Egypt.

When the Egyptian sultan died, a three–way landgrab ensued between Sharwah, the shifty vizier of the Egyptian Fatimid caliph (a ruler who was an incompetent boob), the European crusaders of the kingdom of Jerusalem, and Saladin’s guys. From 1164 to 1168, Saladin jockeyed for control of these rulerless lands, eventually luring Sharwah into an ambush and killing him. When his uncle died shortly thereafter in March of 1169, the thirty–two–year–old Saladin, a reputedly short and frail man, was given the title al–Malik al–Nasir (the prince defender). Uncle Shirkuh would be the first of several people who would conveniently expire just in time for the charismatic commander to rise to power, the second being the Al–Adid, last of the Fatimid caliphs (Shi'a nobles believed to descend from Mohammed's youngest daughter, Fatima, who reigned from 969 to 1171), whose passing gave our Islamic idol command of all Egypt.

Leading a Seljuk army made up mostly of former slaves, Saladin marched to Kahira, where the royal compound was located, and kicked out the caliph’s 18,000 lazy relatives who were crashing there, opening the city to the people. Saladin was a humble man who did not hoard money or live in palaces, and under his fair rule slaves who earned their freedom (known as Mamluks) could gain rank in his army and royal court. People flocked to this new and noble ruler and the population of Kahira swelled. Today it is known as Cairo, which means “the subduer.”

Luckily, before Nur ad-Din could become jealous of his nephew, he died right on cue in May 1174, making Saladin sultan of all Egypt and Syria and the first supreme ruler of the new Ayyubid caliphate. In May 1176, while attacking the town of Aleppo, the Assassins Cult of Rashideddin made their first attempt on Saladin's life, but failed because they didn't count on his judo chop. Saladin responded by besieging the fortress of Masyaf, the Assassin stronghold, in 1176, but withdrew only a few weeks later, some say as a result of threats to his family. (“Ooops sorry, wrong stronghold. We wanted the one two mountains down. Our bad.”)

Around the same time, Saladin began improvements on Cairo, constructing mosques, hospitals (which he even equipped with mental asylums and separate quarters for women), and colleges of Islamic study. He also swept away the governmental corruption that had plagued the Fatimid rule. In a time of physical and spiritual war, Saladin wanted Cairo to be a bastion of Islamic faith, military strength, and a source of income to fund his campaign against the double–crossing crusaders and their infidel–ity. Domestically, Saladin revitalized the Egyptian economy, reorganized the military, and restored Islamism in Egypt, but preferring the Sunni side of the street, he replaced the prevalent Shi’a Islamic doctrines with those of his own faith.

In 1182, Saladin left Egypt in the hands of his brother and marched off to attack the crusaders’ kingdom of Jerusalem, commanding a vast army of Muslims that the crusaders dubbed the Saracens, from the Greek word sarakenoi meaning “easterner,” or “Hey, watch where you're waving that scimitar.” At the Battle of Hattin in 1187, provoked by the underhanded French crusader Raynald de Chatillon and his threats to sack the Islamic holy centers of Medina and Mecca (“Oh, no he di’nt!”), Saladin met and crushed the Christian forces. This battle would ultimately lead to the crusaders’ fall from grace (and power) in the Middle East. Although his army captured several European nobles, Saladin forbade his men from murdering them. He also prohibited raping and pillaging the holy city (but then, where’s the fun?), granting the Christians safe passage home, as opposed to the crusaders who, when sacking Jerusalem back in 1099, butchered everybody in sight.

In 1189, the king of England, Richard I, Coeur de Lion (the Lionhearted guy everyone’s waiting for to come back in Robin Hood), led the Third Crusade to recover the holy city (because the abysmal failure of the first two had been so inspirational), beginning a military rivalry with Saladin that became the stuff of legend. Because of his chivalry, Saladin has been called the “noble Arab” (though despite his fancy galabia he was never called the “chic sheik”), once even sending his enemies fruit and water when Richard fell ill, hoping it would help his upset tummy. Richard’s Crusade, also known as the King’s Crusade, ultimately failed.

In 1192 Saladin reached an agreement with the Western warriors called the Peace of Ramla, allowing them to peacefully withdraw from the region, while still generously permitting Christian pilgrims to trek to Jerusalem unmolested, unless they brought one of those naughty priests, in which case it was out of his hands. In the meantime, Saladin smashed nearly all other Christian cities except Tyre and Jaffa, reducing the once great crusaders' kingdom to ruin. At its height, Saladin's empire spanned the Middle East and North Africa for hundreds of miles, but when he died in Damascus in 1193 at the age of fifty-five, he'd given away all his money to the needy and was buried penniless.

Interesting Tidbit: While he had the city under siege, Saladin once gave a crusader permission to retrieve his family from Jerusalem and leave unscathed. His only condition was that the soldier swore not to stay and fight. When the crusader reached the holy city, the outnumbered defenders persuaded him to take charge of their defenses and he sought release from his oath to Saladin. The noble Arab understood his plight and gave the man’s family safe passage out of the area anyway.

Ways to Bring Up Saladin in Conversation

• Larry really pulled a total Saladin by forgiving Laura for cheating.

• Look out. The way Amy is rising through the ranks, before you know it, we'll be calling her Saladin.

• I want my Middle Eastern chicken salad Saladin style … with chopped white meat.

Manfred von Richthofen’s Life Was a Flying Circus

When Are We Talking About: 1892-1918

Why Are We Even Talking About This: More commonly known as the Red Baron, Manfred von Richthofen is arguably the most famous name in the history of aerial combat and a modern–day legend.

What You Need to Know to Sound Smart: Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen was born on May 2, 1892, in Breslau, Germany, now located in Poland. He was the son of a Prussian nobleman, Maj. Albrecht Richthofen, and his wife, Kunigunde (oh, those erotic Prussian names, "Give it to me, Kunigunde"). An excellent athlete and an even better equestrian, Richthofen was an arrogant, charismatic, and cocky young man, who spent his life in military school, punishment for being unable to pronounce his mother’s name. After graduating from the Royal Military Academy at Lichterfelde, Richthofen became a cavalry officer (like his daddy) in the kaiser’s army and got to wear a cool pointy helmet. When his unit was obliterated in a bloody skirmish, Manfred realized that in modern war the horseman would be put out to pasture and so traded in his saddle for a flight stick.

Inspired by the exploits of German flying ace Oswald Boelcke (who would become both a mentor and a friend), Richthofen began studying piloting and proved himself an apt aerial pupil. His aviation career first took flight in 1915 when he soloed after only twenty–four hours of training. Richthofen quickly soared to fame as a deadly dogfighter but didn’t gain his legendary nom de guerre (French for “my real name sucks monkey butt”) until his fellow Germans, never renowned for their good judgment, mistook his plane for an enemy aircraft and opened fire as he flew overhead. Cursing, Richthofen limped from his newly air–conditioned craft to the supply shed and covered the entire plane in a coat of red paint to ensure that troops in the future could tell Manfred from foe. Thus, the Red Baron was born.

In 1917, Richthofen formed and commanded the Flying Circus, a squadron of Germany’s top aces, though they were never known to cram thirty pilots into a single plane. This “brat-wurst pack” instantly became the terror of the skies during World War I, causing their British enemies to spontaneously “drop fuel” as Richthofen led them screaming out of the clouds. During his career, Manfred and his Fokker DR-1 triplane were credited with eighty kills, giving him the high score for WWI. However, by the end of the war, Richthofen, disenchanted and disillusioned, suffered from headaches, combat wounds, and terrible bouts of depression having watched all his friends die in battle. On April 21, 1918, near Sailly–le–Sac, France, the Red Baron was finally killed by a single bullet through his chest while, contrary to his own tactical teachings, he flew deep over enemy lines at low altitude in pursuit of a novice British pilot. He was only twenty–five.

Controversy persists to this day as to whether Manfred was shot down by the pilot he was chasing or the Australian infantry gunners he was soaring over. Richthofen was such a respected adversary that the British buried him with full military honors in France, but his body was eventually moved to his family's cemetery in Wiesbaden in 1976.

Interesting Tidbit: Richthofen was the most famous man in Germany during WWI and, like a modern-day sports star, he even had his own trading cards as well as other types of “merch,” which kids collected throughout the country.

Ways to Bring Up von Richthofen in Conversation

• I don’t trust that airline. They’ve had more confirmed kills than Richthofen.

• That guy’s a killer. He's the Red Baron of dating.

• Amanda lives like Richthofen flew, fast and furious.

The War Conversation

The sadly useful thing about the war conversation is that there’s always some kind of bloodshed going on somewhere in the world, and so it's easy to bring up. Though military history has been traditionally a guy topic, these days it's quite likely that in a room full of people of either sex someone will have served or at least had a sibling, significant other, or “ex” who did. Certainly, if you’re attending any armed forces related affair, familiarizing yourself with a few topics in the war conversation will help you win friends and get people talking. However, be mindful that you are likely to find a handful of Experts (see the Appendix, Who’s Who at the Party) in the crowd who will give you a run for your military money. So once things are rolling, consider where to take the talk next. Generally, military buffs tend to like video games, sports, action flicks (war movies), and politics. It’s worth noting, if you're dealing with people in the actual military, it’s a good rule of thumb to stay clear of criticizing the government, unless you get the sense that the people you’re dealing with have liberal, or at the very least, tolerant views.

Hannibal Was Republic Enemy Number One

When Are We Talking About: 247 BC-183 BC

Why Are We Even Talking About This: Hannibal was one of the most famous military commanders in history, who impossibly led his army (including cavalry and elephants), across the Swiss Alps into the heart of the Roman Empire, not only surprising the Roman legions but nearly destroying them.

What You Need to Know to Sound Smart: Hannibal Barca was born in Carthage (near modern-day Tunis), North Africa, in 247 BC, the son of Hamilcar (boy, they sure had great names in Carthage, didn't they?), the general who defended Sicily against the Romans in the First Punic War (nothing like the Pubic War waged by penis enlargement companies on the Internet). While most dads teach their boys to play baseball and fish, Hamilcar despised the Roman Empire and kindled the same hatred in Hannibal. With training-spear in hand, ten-year-old Hannibal traveled with his father to war in Spain, and by age twenty-six was a general, replacing his dead brother-in-law, Hasdrubal (a name ripe for telemarketer screwups: “Is Mr. Haysdrooble in? Well, is Mrs. Haysdrooble there?”) In 223 BC, Hannibal attacked and conquered Saguntum, modern-day Sagunto (wherever the hell that is…just kidding, it's in Spain), and won the support of his native city, thus laying the foundation for what would become the Second Punic War (218-201 BC).

Fed up with Roman imperialism (he preferred his own), Hannibal decided to surprise the Roman army by taking the fight to them. In a daring and nearly suicidal move, Hannibal led his Carthaginian army, including baggage train (that is, food supplies, not that blind date you had who unloaded all of his problems on you the first time you got together for tuna rolls), on foot across the Alps, a total of 1,500 miles with not a freeway or HoJo’s in sight. Hannibal appeared unexpectedly in Northern Italy and fell upon the undefended Po Valley (218-217 BC), catching the Roman soldiers with their togas down around their ankles.

As word of Hannibal’s victories spread, new recruits from Rome’s other enemies (like everyone in civilization) flocked to his banner, following Hannibal as he defeated several Roman armies (mind you, the mightiest military force in the world at that time), sometimes while outnumbered four to one. At the famed Battle of Cannae, Hannibal brilliantly used his cavalry to outflank the Romans, who had twice as many soldiers, and destroyed their army to a man. (His name was Frederico and he was a snappy dresser.) Between 25,000 and 50,000 Romans were slain and 10,000 captured, compared to Hannibal's 5,700, of which the vast majority were Celts and Iberians (Spanish).

With this great victory, Southern Italy rose up against the empire, joining Hannibal, as he threatened to end the power of Rome a few centuries earlier than scheduled. However, internal squabbles from the nimrods back in Carthage resulted in the loss of financial support, and Hannibal was left to survive on traveler's checks. (“Hey, guys, just like twenty more bucks and I could finish this.”) Hannibal refused to go home, and instead hung out in Italy, touring the cities with his army, sacking wherever he went if his rigatoni wasn’t al dente and crushing any who dared to face him, until Roman generals were too afraid to take the field (imagine if Mexicans invaded Texas and took over the entire southern half of the state and the U.S. government was helpless to stop them … well, just imagine Texas). Hannibal was at last recalled to defend his home city against a young Roman commander, Scipio Africanus, who at the Battle of Zama (Africa), finally conquered the Carthaginian commander.

Hannibal retired from military life in 200 BC, but four years later, began to publicly lash out at his city’s corrupt aristocracy. The powers that be, fearing Hannibal's influence, sold him out to the Romans (who still had a Punic bone to pick with him for rubbing their noses in the elephant poo he left all over their country) by falsely accusing him of plotting another attack on Rome. In an incredible strategic blunder, Hannibal launched a surprise assault against the Empire (“They think I'm gonna attack, but what they don’t know is … I'm gonna attack!”). But as we said, the Romans did know and had a massive welcome back party waiting. Consequently, Hannibal was forced to retreat to Asia Minor in 183 BC, where the Romans pressured the local ruler, Prusias I, for his surrender (“If you give us Hannibal, we’ll give you working toilets. Whaddya say?”). Trapped and out of options, rather than give in to his lifelong enemy, Hannibal poisoned himself in Libyssa, Turkey. Death by street kebab, what a way to go.

Interesting Tidbit: When his son was just nine years old, before departing on the Spanish campaign, Hamilcar took Hannibal to the altar and made him repeat this oath, “I swear that so soon as age will permit, I will use fire and steel to arrest the destiny of Rome.” Hatred truly does begin in the home.

Ways to Bring Up Hannibal in Conversation

• There’s more foreigners here than in Hannibal's army.

• That guy is the Hannibal of my existence, always popping up unexpectedly and making my life miserable.

• I’m having a Hannibal day. I feel like I’m winning the battle, but losing the war.

Saladin Won the Noble Prize During the Crusades

When Are We Talking About: 1138-1193

Why Are We Even Talking About This: Saladin was the notoriously fair and chivalrous sultan of Egypt and the greatest general to face the European crusaders. He conquered Jerusalem and restored Sunnism to Egypt and Syria.

What You Need to Know to Sound Smart: Salah ad-Din Yusuf Ibn Ayyub (or Saladin, to anyone living west of the Nile) was born in Tikrit, Mesopotamia, around 1138, to a wealthy Kurdish family in northern Iraq (you know, the people from the old “no fly zone”), but grew up in the court of Nur ad–Din, the ruler of Syria, the caliph of Damascus, kind of like a state governor but with camels. In the court, he studied the Koran, philosophy, the Koran, military history, the Koran, the Koran, poetry and followed that up with a little bedtime Koran. At age fourteen, when most young boys are mastering Halo2, Saladin (meaning Righteous of the Faith) joined his uncle Shirkuh’s military staff on a campaign into Egypt.

When the Egyptian sultan died, a three–way landgrab ensued between Sharwah, the shifty vizier of the Egyptian Fatimid caliph (a ruler who was an incompetent boob), the European crusaders of the kingdom of Jerusalem, and Saladin’s guys. From 1164 to 1168, Saladin jockeyed for control of these rulerless lands, eventually luring Sharwah into an ambush and killing him. When his uncle died shortly thereafter in March of 1169, the thirty–two–year–old Saladin, a reputedly short and frail man, was given the title al–Malik al–Nasir (the prince defender). Uncle Shirkuh would be the first of several people who would conveniently expire just in time for the charismatic commander to rise to power, the second being the Al–Adid, last of the Fatimid caliphs (Shi'a nobles believed to descend from Mohammed's youngest daughter, Fatima, who reigned from 969 to 1171), whose passing gave our Islamic idol command of all Egypt.

Leading a Seljuk army made up mostly of former slaves, Saladin marched to Kahira, where the royal compound was located, and kicked out the caliph’s 18,000 lazy relatives who were crashing there, opening the city to the people. Saladin was a humble man who did not hoard money or live in palaces, and under his fair rule slaves who earned their freedom (known as Mamluks) could gain rank in his army and royal court. People flocked to this new and noble ruler and the population of Kahira swelled. Today it is known as Cairo, which means “the subduer.”

Luckily, before Nur ad-Din could become jealous of his nephew, he died right on cue in May 1174, making Saladin sultan of all Egypt and Syria and the first supreme ruler of the new Ayyubid caliphate. In May 1176, while attacking the town of Aleppo, the Assassins Cult of Rashideddin made their first attempt on Saladin's life, but failed because they didn't count on his judo chop. Saladin responded by besieging the fortress of Masyaf, the Assassin stronghold, in 1176, but withdrew only a few weeks later, some say as a result of threats to his family. (“Ooops sorry, wrong stronghold. We wanted the one two mountains down. Our bad.”)

Around the same time, Saladin began improvements on Cairo, constructing mosques, hospitals (which he even equipped with mental asylums and separate quarters for women), and colleges of Islamic study. He also swept away the governmental corruption that had plagued the Fatimid rule. In a time of physical and spiritual war, Saladin wanted Cairo to be a bastion of Islamic faith, military strength, and a source of income to fund his campaign against the double–crossing crusaders and their infidel–ity. Domestically, Saladin revitalized the Egyptian economy, reorganized the military, and restored Islamism in Egypt, but preferring the Sunni side of the street, he replaced the prevalent Shi’a Islamic doctrines with those of his own faith.

In 1182, Saladin left Egypt in the hands of his brother and marched off to attack the crusaders’ kingdom of Jerusalem, commanding a vast army of Muslims that the crusaders dubbed the Saracens, from the Greek word sarakenoi meaning “easterner,” or “Hey, watch where you're waving that scimitar.” At the Battle of Hattin in 1187, provoked by the underhanded French crusader Raynald de Chatillon and his threats to sack the Islamic holy centers of Medina and Mecca (“Oh, no he di’nt!”), Saladin met and crushed the Christian forces. This battle would ultimately lead to the crusaders’ fall from grace (and power) in the Middle East. Although his army captured several European nobles, Saladin forbade his men from murdering them. He also prohibited raping and pillaging the holy city (but then, where’s the fun?), granting the Christians safe passage home, as opposed to the crusaders who, when sacking Jerusalem back in 1099, butchered everybody in sight.

In 1189, the king of England, Richard I, Coeur de Lion (the Lionhearted guy everyone’s waiting for to come back in Robin Hood), led the Third Crusade to recover the holy city (because the abysmal failure of the first two had been so inspirational), beginning a military rivalry with Saladin that became the stuff of legend. Because of his chivalry, Saladin has been called the “noble Arab” (though despite his fancy galabia he was never called the “chic sheik”), once even sending his enemies fruit and water when Richard fell ill, hoping it would help his upset tummy. Richard’s Crusade, also known as the King’s Crusade, ultimately failed.

In 1192 Saladin reached an agreement with the Western warriors called the Peace of Ramla, allowing them to peacefully withdraw from the region, while still generously permitting Christian pilgrims to trek to Jerusalem unmolested, unless they brought one of those naughty priests, in which case it was out of his hands. In the meantime, Saladin smashed nearly all other Christian cities except Tyre and Jaffa, reducing the once great crusaders' kingdom to ruin. At its height, Saladin's empire spanned the Middle East and North Africa for hundreds of miles, but when he died in Damascus in 1193 at the age of fifty-five, he'd given away all his money to the needy and was buried penniless.

Interesting Tidbit: While he had the city under siege, Saladin once gave a crusader permission to retrieve his family from Jerusalem and leave unscathed. His only condition was that the soldier swore not to stay and fight. When the crusader reached the holy city, the outnumbered defenders persuaded him to take charge of their defenses and he sought release from his oath to Saladin. The noble Arab understood his plight and gave the man’s family safe passage out of the area anyway.

Ways to Bring Up Saladin in Conversation

• Larry really pulled a total Saladin by forgiving Laura for cheating.

• Look out. The way Amy is rising through the ranks, before you know it, we'll be calling her Saladin.

• I want my Middle Eastern chicken salad Saladin style … with chopped white meat.

Manfred von Richthofen’s Life Was a Flying Circus

When Are We Talking About: 1892-1918

Why Are We Even Talking About This: More commonly known as the Red Baron, Manfred von Richthofen is arguably the most famous name in the history of aerial combat and a modern–day legend.

What You Need to Know to Sound Smart: Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen was born on May 2, 1892, in Breslau, Germany, now located in Poland. He was the son of a Prussian nobleman, Maj. Albrecht Richthofen, and his wife, Kunigunde (oh, those erotic Prussian names, "Give it to me, Kunigunde"). An excellent athlete and an even better equestrian, Richthofen was an arrogant, charismatic, and cocky young man, who spent his life in military school, punishment for being unable to pronounce his mother’s name. After graduating from the Royal Military Academy at Lichterfelde, Richthofen became a cavalry officer (like his daddy) in the kaiser’s army and got to wear a cool pointy helmet. When his unit was obliterated in a bloody skirmish, Manfred realized that in modern war the horseman would be put out to pasture and so traded in his saddle for a flight stick.

Inspired by the exploits of German flying ace Oswald Boelcke (who would become both a mentor and a friend), Richthofen began studying piloting and proved himself an apt aerial pupil. His aviation career first took flight in 1915 when he soloed after only twenty–four hours of training. Richthofen quickly soared to fame as a deadly dogfighter but didn’t gain his legendary nom de guerre (French for “my real name sucks monkey butt”) until his fellow Germans, never renowned for their good judgment, mistook his plane for an enemy aircraft and opened fire as he flew overhead. Cursing, Richthofen limped from his newly air–conditioned craft to the supply shed and covered the entire plane in a coat of red paint to ensure that troops in the future could tell Manfred from foe. Thus, the Red Baron was born.

In 1917, Richthofen formed and commanded the Flying Circus, a squadron of Germany’s top aces, though they were never known to cram thirty pilots into a single plane. This “brat-wurst pack” instantly became the terror of the skies during World War I, causing their British enemies to spontaneously “drop fuel” as Richthofen led them screaming out of the clouds. During his career, Manfred and his Fokker DR-1 triplane were credited with eighty kills, giving him the high score for WWI. However, by the end of the war, Richthofen, disenchanted and disillusioned, suffered from headaches, combat wounds, and terrible bouts of depression having watched all his friends die in battle. On April 21, 1918, near Sailly–le–Sac, France, the Red Baron was finally killed by a single bullet through his chest while, contrary to his own tactical teachings, he flew deep over enemy lines at low altitude in pursuit of a novice British pilot. He was only twenty–five.

Controversy persists to this day as to whether Manfred was shot down by the pilot he was chasing or the Australian infantry gunners he was soaring over. Richthofen was such a respected adversary that the British buried him with full military honors in France, but his body was eventually moved to his family's cemetery in Wiesbaden in 1976.

Interesting Tidbit: Richthofen was the most famous man in Germany during WWI and, like a modern-day sports star, he even had his own trading cards as well as other types of “merch,” which kids collected throughout the country.

Ways to Bring Up von Richthofen in Conversation

• I don’t trust that airline. They’ve had more confirmed kills than Richthofen.

• That guy’s a killer. He's the Red Baron of dating.

• Amanda lives like Richthofen flew, fast and furious.

Descriere

In 14 pain-free, laughter-filled chapters, the authors brush away years of cobwebs on subjects as wide-ranging as the typical round of "Jeopardy": war, science, politics, philosophy, the arts, business, literature, music, religion, and more.