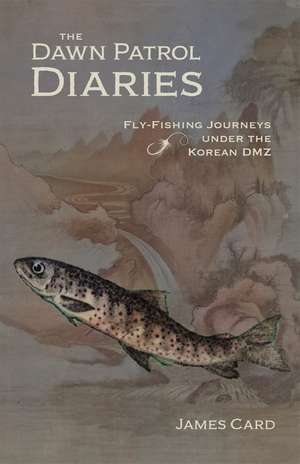

The Dawn Patrol Diaries: Fly-Fishing Journeys under the Korean DMZ: Outdoor Lives

Autor James Carden Limba Engleză Paperback – sep 2024

In The Dawn Patrol Diaries Card writes about fly-fishing as well as South Korean landscape and culture. His travels range from the borders of the DMZ to inland mountain trout streams, from the rugged southern coast to the tidal flats of the western coast. He goes fly-fishing where battles of the Korean War were fought and offers vivid descriptions of the last wildlands in South Korea as well as insightful observations on the perils facing Korean cities, villages, and farms.

Preț: 135.03 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 203

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.84€ • 28.06$ • 21.71£

25.84€ • 28.06$ • 21.71£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Livrare express 18-22 martie pentru 49.60 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781496234490

ISBN-10: 1496234499

Pagini: 248

Ilustrații: 30 photographs

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.37 kg

Editura: Nebraska

Colecția University of Nebraska Press

Seria Outdoor Lives

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 1496234499

Pagini: 248

Ilustrații: 30 photographs

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.37 kg

Editura: Nebraska

Colecția University of Nebraska Press

Seria Outdoor Lives

Locul publicării:United States

Notă biografică

James Card lived in South Korea for twelve years working as a freelance journalist and fly-fishing guide. He has written for the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, Rolling Stone, The Drake, and other publications.

Extras

1 The Red Quest

It was only a few months after I arrived in Tongyeong when an envelope

from overseas was delivered to my school. It had been postmarked in South

Dakota. Inside were two letters. One was a sheaf of photocopied papers:

a handwritten letter. The other was a handwritten letter that had been

written recently, with a yellowed newspaper clipping. The photocopied

letter was to my grandfather, my grandmother, and my mother. It was

dated December 15, 1951.

Dear Verna, Eldo, Cheryl,

I can’t start this letter off without saying thanks for the letter

you sent as I haven’t got any mail since I left Japan but in about

a week or two, I should get some mail. Until then I’ll just keep

reading the ones I got in Japan.

Well, I’m no longer in the pipeline status in the service I’m

now a member of the headquarters and in service of the 65th

Engineers of the 25th Tropic Yellow Lightning Division. Our

shoulder patch is red with a yellow border and a jagged line

of yellow. As of yet I don’t know what I will be doing but they

all say I’ll be in the maintenance shops and they are tents but

that’s the same in my line. We are about eight miles back of the

lines and all we hear now is the artillery. Otherwise, it’s pretty

quiet around here.

I got to keep the m1 rifle they gave me at the replacement

center and one of the guys looked at it when I was cleaning

it and he said it was like new. It sure works smoother than

before we left the replacement center. They gave us two clips

of ammo and we rode in on open tracks and we thought it was

terrible until the driver said when you are that close a plane

can stray over and if it’s not friendly, you don’t want anything

in the way of getting out and I agreed.

We sure do eat good here, three meals a day and all you

want to eat so boy we won’t be hungry. The way it started on

the train—getting c-rations—we all thought that is what it

would be living on but we sure were mistaken. I’ve got two

bandoliers of ammo I found under my bunk and there is plenty

everywhere you go. Everyone is very well equipped as much

as clothing and personal needs. We get a px ration every night.

It’s for a pack of cigarettes or pipe tobacco, candy bars, gum,

soap, razor blades, and tooth powder or paste so you see the

guys are well taken care of but of course you only take what

you want or need but it’s all free.

The country here is all hilly like the cactus hills back home—only

the hills get bigger and bigger as you move north. Most

all the people here are farmers. They have rice paddies in the

hollows and terraces on the slants of the hills where they grow

other things. They either walk or ride bicycles. Mostly they

walk and then to get stuff to town, if they have an ox, they haul

it on a four or two wheeled wagon. Otherwise, they carry it on

their heads in great big bundles and they walk along fast and

never hold the bundles with their hands. They live in shacks

about like the rabbit houses Grandpa used to have.

On the way up here we seen Seoul, the capital city, and boy it

is a mess. The buildings are all blown up and you can sure see

that Uncle’s boys have been through here. The funniest thing

I saw was one big stone building with only the front of it left

standing. The doors to it were closed and no windows were in

it. I sure thought it looked odd.

The guys I’m with seem to be very nice and the old guy who

I got acquainted with at the replacement center is with me

in the hq but he’s in the next bunker. Our bunkers are in the

hillside and made of logs and then covered with dirt so it’s

nice and warm as there are no drafts. We have a stove, electric

lights, and a radio set up so you can hear through ear phones—I’m

listening to it now. The sergeant in our bunker says I won’t

be given a job until after we get to where we are going as this

outfit is going into reserve for a while. I don’t know for how

long but we are moving out in a day or so. It’s sort of cool now

in the early part of the day—otherwise it’s not too bad.

I sent Cheryl a hankie in mom’s one letter but it wasn’t much

but we aren’t in a position right now where we can send

anything but when we can I’m going to send some more stuff.

Hope this finds you all well and happy. I’m feeling fine and I’m

getting along nicely so don’t worry about me as I’ve got the

good keeper on my side to take care of me and I’m sure going

to help him do his job. So bye now.

Lots of love and kisses,

Uncle Clayton

I unfolded the second letter and set aside the newspaper clipping.

Dear Jim,

I’ve been going to write to you for a long time and now finally

Grandma found the paper with your address on it so here goes.

Your Grandma called and asked Marty if I ever wrote to you

about the places I was at and that really got her looking.

To start off: “My friends and neighbors have selected you to

serve in the U.S. Army.”

I was sworn in on the 26th of April 1951. I went to Fort Lewis,

Washington, then across the country to the Aberdeen Proving

Grounds and six weeks of basic training and then to Atlanta,

Georgia to the ordnance training school and of course they

made a welder out of this farm boy.

The school lasted ten weeks, then fifteen days of furlough time

at home and I was on my way to Seattle, Washington and Pier

91. We sailed out to Japan and to Korea on the Marine Adder.

We were in Japan for thirty-six hours and were assigned to

our units in Korea. Back on our ships and more big waves and

bobbing up and down.

We had to anchor way out in Inchon Harbor as the tide was

out, so we got one more cooked meal on the boat and got in

closer to shore and climbed down the side of the ship on a

net into the landing barges. They ran aground and dropped

the end down and everyone sloshed out through the mud and

water. We marched in rank and loaded into narrow-gauge

box cars that had wood bunks, or more like shelves to lay on when

all the guys were loaded, we went to the replacement depot.

There we slept in an old hospital building if my memory

is right, it was like four stories tall, just the four walls and

window holes and the bottom cement floor was like sleeping

on ice. They said no lights of any kind flashlights or lighters

or smoking. Then we got a can of c-rations to eat—hot on the

outside, still froze in the middle (I’ve got my plastic spoon I

ate that with).

Grandma took a map somebody sent me out of the Sioux

Falls paper and is getting a copy made of it. I drew lines with

arrows of where I went and the places we were stationed at

and worked from are circled. There are lots of areas that had

names that aren’t on the map like The Fingers (hills like a

hand), the Iron Triangle, Jane Russell, Sandbag Castle and

the Punchbowl. We did a lot of work and war there. We

built supply roads and bridges in two directions out of the

Punchbowl, both to the front lines and out from there.

My sidekick on these bridges was Jensen, a Swede from Iron

Mountain, Michigan. He’d always weld “Red Jensen” on one

end of the bridge and the date of completing it. One of these,

C Company 65th combat engineers built when it was minus

ten below zero when we welded it together in open water in

the middle of the river, the name of it I don’t remember.

Along the ridgelines of the Punchbowl was a road called

Skyline Drive. It was a bad road to travel as some of it you had

to drive on top in plain sight and it wasn’t good enough to

drive fast on so you always got some “stones” thrown at you in

those spots = boom! and dirt and rocks raining down on you

and your welding truck. It was always said if you hear the noise

and feel the rocks you are lucky.

The coldest temperature I seen there was minus thirty-five

below zero. It froze our diesel fuel we used in our tractors and

tent stoves solid. I got ours burning by mixing gas in it—very

dangerous to do. In times like that a tent with one small stove

is very cold to live in. The hottest temperature I seen there was

112 degrees. Three of us took turns cutting with a torch making

some big pulleys for some supply line tramways for reaching

the hilltop trenches and for bringing down wounded guys.

You’d cut till your colored glasses filled with sweat and then

hand it to another guy.

If you’ve got a map, you can compare it to this one and you

may find some of the towns.

Love,

Uncle Clayton

It was from my great-uncle on my mother’s side of the family. I remember

playing at his farm in South Dakota when I was a boy. I rode horses,

blasted fireworks, and shot many guns. The first semiautomatic weapon

I ever fired was his Remington Nylon 66. I spent an afternoon picking off

gophers with the rifle in his pasture. I remember him with great fondness.

I looked at the map from the old news clipping and matched it up with a

map that I kept on my desk. The Korean War was nicknamed the “Forgotten

War.” It was overshadowed and bookended in American consciousness

by World War II and the Vietnam War. No peace treaty was ever signed.

There was only an armistice, as if a pause button was pushed. The rifles

were never put down. The area where my uncle served is the northernmost

region of South Korea, and I lived in a small city on the far southern

coast. Somewhere up by the dmz were bridges that my uncle had built as

a combat engineer during the Korean War, and a guy that he worked with

had welded his name on these bridges. I vowed to find one of them.

It was only a few months after I arrived in Tongyeong when an envelope

from overseas was delivered to my school. It had been postmarked in South

Dakota. Inside were two letters. One was a sheaf of photocopied papers:

a handwritten letter. The other was a handwritten letter that had been

written recently, with a yellowed newspaper clipping. The photocopied

letter was to my grandfather, my grandmother, and my mother. It was

dated December 15, 1951.

Dear Verna, Eldo, Cheryl,

I can’t start this letter off without saying thanks for the letter

you sent as I haven’t got any mail since I left Japan but in about

a week or two, I should get some mail. Until then I’ll just keep

reading the ones I got in Japan.

Well, I’m no longer in the pipeline status in the service I’m

now a member of the headquarters and in service of the 65th

Engineers of the 25th Tropic Yellow Lightning Division. Our

shoulder patch is red with a yellow border and a jagged line

of yellow. As of yet I don’t know what I will be doing but they

all say I’ll be in the maintenance shops and they are tents but

that’s the same in my line. We are about eight miles back of the

lines and all we hear now is the artillery. Otherwise, it’s pretty

quiet around here.

I got to keep the m1 rifle they gave me at the replacement

center and one of the guys looked at it when I was cleaning

it and he said it was like new. It sure works smoother than

before we left the replacement center. They gave us two clips

of ammo and we rode in on open tracks and we thought it was

terrible until the driver said when you are that close a plane

can stray over and if it’s not friendly, you don’t want anything

in the way of getting out and I agreed.

We sure do eat good here, three meals a day and all you

want to eat so boy we won’t be hungry. The way it started on

the train—getting c-rations—we all thought that is what it

would be living on but we sure were mistaken. I’ve got two

bandoliers of ammo I found under my bunk and there is plenty

everywhere you go. Everyone is very well equipped as much

as clothing and personal needs. We get a px ration every night.

It’s for a pack of cigarettes or pipe tobacco, candy bars, gum,

soap, razor blades, and tooth powder or paste so you see the

guys are well taken care of but of course you only take what

you want or need but it’s all free.

The country here is all hilly like the cactus hills back home—only

the hills get bigger and bigger as you move north. Most

all the people here are farmers. They have rice paddies in the

hollows and terraces on the slants of the hills where they grow

other things. They either walk or ride bicycles. Mostly they

walk and then to get stuff to town, if they have an ox, they haul

it on a four or two wheeled wagon. Otherwise, they carry it on

their heads in great big bundles and they walk along fast and

never hold the bundles with their hands. They live in shacks

about like the rabbit houses Grandpa used to have.

On the way up here we seen Seoul, the capital city, and boy it

is a mess. The buildings are all blown up and you can sure see

that Uncle’s boys have been through here. The funniest thing

I saw was one big stone building with only the front of it left

standing. The doors to it were closed and no windows were in

it. I sure thought it looked odd.

The guys I’m with seem to be very nice and the old guy who

I got acquainted with at the replacement center is with me

in the hq but he’s in the next bunker. Our bunkers are in the

hillside and made of logs and then covered with dirt so it’s

nice and warm as there are no drafts. We have a stove, electric

lights, and a radio set up so you can hear through ear phones—I’m

listening to it now. The sergeant in our bunker says I won’t

be given a job until after we get to where we are going as this

outfit is going into reserve for a while. I don’t know for how

long but we are moving out in a day or so. It’s sort of cool now

in the early part of the day—otherwise it’s not too bad.

I sent Cheryl a hankie in mom’s one letter but it wasn’t much

but we aren’t in a position right now where we can send

anything but when we can I’m going to send some more stuff.

Hope this finds you all well and happy. I’m feeling fine and I’m

getting along nicely so don’t worry about me as I’ve got the

good keeper on my side to take care of me and I’m sure going

to help him do his job. So bye now.

Lots of love and kisses,

Uncle Clayton

I unfolded the second letter and set aside the newspaper clipping.

Dear Jim,

I’ve been going to write to you for a long time and now finally

Grandma found the paper with your address on it so here goes.

Your Grandma called and asked Marty if I ever wrote to you

about the places I was at and that really got her looking.

To start off: “My friends and neighbors have selected you to

serve in the U.S. Army.”

I was sworn in on the 26th of April 1951. I went to Fort Lewis,

Washington, then across the country to the Aberdeen Proving

Grounds and six weeks of basic training and then to Atlanta,

Georgia to the ordnance training school and of course they

made a welder out of this farm boy.

The school lasted ten weeks, then fifteen days of furlough time

at home and I was on my way to Seattle, Washington and Pier

91. We sailed out to Japan and to Korea on the Marine Adder.

We were in Japan for thirty-six hours and were assigned to

our units in Korea. Back on our ships and more big waves and

bobbing up and down.

We had to anchor way out in Inchon Harbor as the tide was

out, so we got one more cooked meal on the boat and got in

closer to shore and climbed down the side of the ship on a

net into the landing barges. They ran aground and dropped

the end down and everyone sloshed out through the mud and

water. We marched in rank and loaded into narrow-gauge

box cars that had wood bunks, or more like shelves to lay on when

all the guys were loaded, we went to the replacement depot.

There we slept in an old hospital building if my memory

is right, it was like four stories tall, just the four walls and

window holes and the bottom cement floor was like sleeping

on ice. They said no lights of any kind flashlights or lighters

or smoking. Then we got a can of c-rations to eat—hot on the

outside, still froze in the middle (I’ve got my plastic spoon I

ate that with).

Grandma took a map somebody sent me out of the Sioux

Falls paper and is getting a copy made of it. I drew lines with

arrows of where I went and the places we were stationed at

and worked from are circled. There are lots of areas that had

names that aren’t on the map like The Fingers (hills like a

hand), the Iron Triangle, Jane Russell, Sandbag Castle and

the Punchbowl. We did a lot of work and war there. We

built supply roads and bridges in two directions out of the

Punchbowl, both to the front lines and out from there.

My sidekick on these bridges was Jensen, a Swede from Iron

Mountain, Michigan. He’d always weld “Red Jensen” on one

end of the bridge and the date of completing it. One of these,

C Company 65th combat engineers built when it was minus

ten below zero when we welded it together in open water in

the middle of the river, the name of it I don’t remember.

Along the ridgelines of the Punchbowl was a road called

Skyline Drive. It was a bad road to travel as some of it you had

to drive on top in plain sight and it wasn’t good enough to

drive fast on so you always got some “stones” thrown at you in

those spots = boom! and dirt and rocks raining down on you

and your welding truck. It was always said if you hear the noise

and feel the rocks you are lucky.

The coldest temperature I seen there was minus thirty-five

below zero. It froze our diesel fuel we used in our tractors and

tent stoves solid. I got ours burning by mixing gas in it—very

dangerous to do. In times like that a tent with one small stove

is very cold to live in. The hottest temperature I seen there was

112 degrees. Three of us took turns cutting with a torch making

some big pulleys for some supply line tramways for reaching

the hilltop trenches and for bringing down wounded guys.

You’d cut till your colored glasses filled with sweat and then

hand it to another guy.

If you’ve got a map, you can compare it to this one and you

may find some of the towns.

Love,

Uncle Clayton

It was from my great-uncle on my mother’s side of the family. I remember

playing at his farm in South Dakota when I was a boy. I rode horses,

blasted fireworks, and shot many guns. The first semiautomatic weapon

I ever fired was his Remington Nylon 66. I spent an afternoon picking off

gophers with the rifle in his pasture. I remember him with great fondness.

I looked at the map from the old news clipping and matched it up with a

map that I kept on my desk. The Korean War was nicknamed the “Forgotten

War.” It was overshadowed and bookended in American consciousness

by World War II and the Vietnam War. No peace treaty was ever signed.

There was only an armistice, as if a pause button was pushed. The rifles

were never put down. The area where my uncle served is the northernmost

region of South Korea, and I lived in a small city on the far southern

coast. Somewhere up by the dmz were bridges that my uncle had built as

a combat engineer during the Korean War, and a guy that he worked with

had welded his name on these bridges. I vowed to find one of them.

Cuprins

List of Illustrations

Romanization and Conversion Note

1. The Red Quest

2. Archipelago of Sword and Spear

3. Fishing the Pusan Perimeter

4. The Boy at Toad-Swarm River

5. Escape Country

6. Piscine Doppelgängers

7. Bear Medicine

8. Field-Expedient Pattern Recognition

9. Under the DMZ

10. The River of Records

11. Into the Karst Kingdom

12. The X-Trout of the Sohan Shut-In

13. The War against Rivers

14. The Child, the Dog, the Ape, and the Dead

15. Little Two-Named River

16. Ninth Station Coda

Postscript

Romanization and Conversion Note

1. The Red Quest

2. Archipelago of Sword and Spear

3. Fishing the Pusan Perimeter

4. The Boy at Toad-Swarm River

5. Escape Country

6. Piscine Doppelgängers

7. Bear Medicine

8. Field-Expedient Pattern Recognition

9. Under the DMZ

10. The River of Records

11. Into the Karst Kingdom

12. The X-Trout of the Sohan Shut-In

13. The War against Rivers

14. The Child, the Dog, the Ape, and the Dead

15. Little Two-Named River

16. Ninth Station Coda

Postscript

Recenzii

"Fly-fishing enthusiasts, lovers of obscure foreign history, and nature geeks alike will find much to enjoy in this well-written and witty narrative."—Josh Bergan, FlyFisherman

“An immersive firsthand account of the enigma that is angling in South Korea, rich with insights into the country’s complicated history, fascinating culture, and resilient nature.”—Stephen Sautner, author of Fish On, Fish Off

“In this book James Card puts his passion, curiosity, and tenacity as an explorer (and fishing fanatic) on full display. It is equal parts natural and cultural history, fly-fishing diary, and homage to his adopted home. Card writes with depth, wit, and deep reverence, and anyone who reads this book will be inspired to visit this paradoxical land of dense humanity and rugged nature, probably packing a fishing rod when they do.”—Steve Hemkens, vice president of global brand strategy for Orvis

“James Card has written a marvelous book, a classic travel-adventure tale that takes readers on a fascinating journey into the rugged mountains of South Korea in search of exotic fish. He finds his fish, but even more, the expatriate Card discovers a rapidly modernizing country whose people and steadily shrinking natural landscapes he learns to love. With his lean, powerful prose, his keen appreciation of nature, and his embrace of risk in the wild, Card is reminiscent of a young Hemingway. Both armchair travelers and lovers of the outdoors will find much to treasure in The Dawn Patrol Diaries.”—Fen Montaigne, author of Reeling in Russia

“James Card may not be the first young American to fall in love with Korea and its people while teaching English there—but he’s certainly unique in turning the experience into a years-long fishing adventure. From spearfishing saltwater fish on Korea’s southern islands to fly-fishing the streams on the edge of the demilitarized zone, Card’s angling memoir brings to life the history, culture, and landscapes of Korea. This is a fishing story like none other.”—Jason Mark, author of Satellites in the High Country and editor in chief of Sierra

Descriere

An outdoor memoir of fly-fishing in South Korea, from the Korean Demilitarized Zone to the mountains, the coasts, and places Korean War battles were fought.