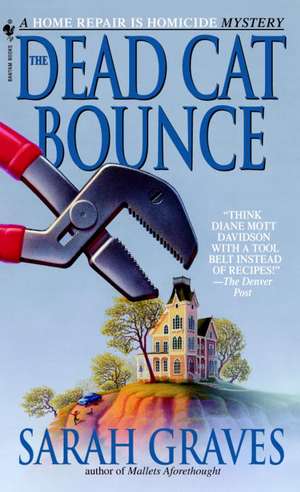

The Dead Cat Bounce: Home Repair Is Homicide Mysteries (Paperback)

Autor Sarah Gravesen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 1998

Since she bought her rambling old fixer-upper of a house, Jacobia Tiptree has gotten used to finding things broken. But her latest problem isn't so easily repaired. Along with the rotting floor joists and sagging support beams, there's the little matter of the dead man in Jake's storeroom, an ice pick firmly planted in his cranium.

Not much happens in her tiny Maine town, but that's about to change. Jake's unknown guest turns out to be a world-famous corporate raider, local boy turned billionaire Threnody McIlwaine. When Jake's best friend, quiet and dependable Ellie White, readily confesses to the murder, cops and journalists swarm into snowbound Eastport.

Jake smells a cover-up, and begins poking into past history between McIlwaine and Ellie's family. But someone doesn't like nosy neighbors...and Jake's rustic refuge may become her final resting place.

Preț: 50.05 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 75

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.58€ • 10.03$ • 7.92£

9.58€ • 10.03$ • 7.92£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553578577

ISBN-10: 055357857X

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 110 x 180 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.16 kg

Editura: CRIMELINE

Seria Home Repair Is Homicide Mysteries (Paperback)

ISBN-10: 055357857X

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 110 x 180 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.16 kg

Editura: CRIMELINE

Seria Home Repair Is Homicide Mysteries (Paperback)

Notă biografică

Sarah Graves lives with her husband in Eastport, Maine, where her mystery novels are set. She is currently at work on her eleventh Home Repair is Homicide novel.

Extras

My house is old, and rambling, and in some disrepair, and I think that it is faintly haunted: a cold spot forming inexplicably on the stairway, a scuttling in the hall. Then of course there is the matter of the enigmatic portrait, whose mystery I had not yet managed to resolve on that bright April morning when, after living cheerfully and peacefully in the house for over a year, I found a body in the storeroom.

Coming upon a body is an experience, like childbirth or a head-on collision, that takes the breath out of a person. I went back through the passageway between the kitchen and the small, unheated room where in spring I kept dog food and dahlia bulbs, and where apparently I now stored corpses.

"Ellie," I said, "there's a dead man out there on the floor."

Ellie White looked up from the kitchen workbench where she was planting pepper seeds, sprinkling a few into each little soil-filled peat pot, to be set out later in the cold frame. Ellie has coppery hair cut short around a thin, serious face lightly dusted with freckles; her pale blue eyes are so intense that even through her glasses, her gaze makes you feel your X-ray is being taken.

Her index finger paused in the act of tamping soil onto a pepper seed. "Who?" she asked.

Sometimes I think Ellie has formaldehyde in her veins. For instance, when I moved to Maine I thought sill work meant painting them, and if you have ever restored an elderly house you will understand the depths of my innocence; sill work is slightly less radical than tearing the house down and starting over entirely, and almost as expensive, and if you don't do it the old house ends up at the bottom of the cellar-hole.

Ellie, upon hearing that this was what my old house needed, merely remarked how lucky I was that I could pay for it, because she knew of another woman whose house had needed sill work, too, and that woman was now living in the cellar-hole. Ellie's comment shut me up pretty quickly, as she had intended, and I resigned myself to getting the job done in spring, but along about March I'd discovered that sill work was only the beginning. There was also the poignant little problem of the rot-raddled floor joists, and of the support beams holding up the floor joists.

Or rather, not holding them up. "I don't know who. He's lying facedown in the corner where everything sags. I should have had that floor jacked up last autumn."

Ellie was wearing denim coveralls, a bright yellow turtleneck with jade-green turtles satin-stitched onto it, and shiny green gardening clogs over thick, yellow socks. On anyone else the outfit would have been hilarious, but Ellie is so tall and slender that she could wear a painter's drop cloth, possibly with a couple of frayed dishrags belted around it, and still look just like a Paris runway model.

"I don't think the floor is the issue here," she said.

"That's because it's not your floor. The only thing holding that floor up now is habit, and when the homicide detectives and the medical examiner and I don't know who all else start tramping in and out of there, then that floor is going to ..."

She was looking at me as if I'd just arrived from Mars. "Jacobia," she said, "I don't know what kind of law enforcement you got used to, back in the big city where you come from."

She picked up the telephone, dialed George Valentine's number, and let it ring. "But in case you haven't noticed, you're not in New York anymore. You're in Eastport, Maine, three hours from Bangor and a heck of a lot farther from anywhere else, and the only person tramping in and out of that storeroom is going to be George. That is, if he ever answers his phone. He was over at my house earlier, but I don't know where he is now."

Of course it was George's number. In Eastport, George was it: if you had a fire, or a flood, or a skunk in the crawlspace, George was the man you wanted, which was lucky since the rest were out on fishing boats: dragging for scallops, hauling lobster pots, or collecting sea urchins, depending upon the season.

"I'm going out there," Ellie said, after George had picked up at last and promised to be right over.

People in Eastport do not think the telephone grows naturally out of the tympanic membrane, and some of them will actually decide whether to answer it or not based on what sort of news they are expecting. But George always answered his telephone sooner or later on account of being the clam warden, on call to make sure diggers had valid clam licenses, chase poachers out of forbidden clam areas, and spot-check the clams themselves with his two-inch metal claim ring, through which a legally harvestable bivalve must not be able to pass.

"I think," Ellie added, "we should make sure the man is really dead."

This struck me as pointless, since an ice pick in the cranium promised little in the way of future prospects. But Ellie was determined; it was part of her downeast Maine heritage, like being able to navigate in the fog or knowing how to dress out a deer.

"It might be he's only wounded," Ellie said. "It might be we can still do something for him."

Right, and it might be that next we could multiply some loaves and fishes. When she had gone I ran a glass of water and stood there by the sink, pondering whether to drink it or not. Just breathing in and out suddenly seemed to require a series of massive, separately considered decisions, as if each small action of mine had abruptly become huge compared to all the ones the dead man was not taking.

Outside my kitchen window a flock of cedar waxwings descended on the crabapple tree and began devouring frozen fruit, their short, metallic cries creating a happy clamor. A shower of snow as fine as salt fell around them, whitening the snow already lying on the ground, so their lime-green feathers and candy-corn beaks stood out as brightly as paint drops.

Down at the breakwater, the big ship Star Verlanger sounded her massive horn and cast off, loaded with paper pulp, and the dockworkers jumped in their pickup trucks and headed for a well-earned bottle of Narragansett beer, no bottle of which the dead man would be enjoying. I wondered if his absence would be noticed, or if he was from away. Whichever; by tonight, news of his death would be all over town.

That was what I thought when the whole thing began. But back then, I didn't know the half of it.

* * *

My name is Jacobia Tiptree, and my ex-husband says I am insane. I have proved this, he says, by giving up a perfectly charming little townhouse on the upper east side of Manhattan--complete with doorman, elevator, and building superintendent--for a huge antique structure every centimeter of which needs paint, plaster, or the underpinnings required to hold up both. The roof leaks, the gutters dangle, and the bricks in the chimneys are quietly turning to sand; when the wind blows hard, which it does very often here, the windows rattle as if they are trying to jump out of their frames, and if you put a marble down on the kitchen floor it will probably roll forever.

I found the place on a warm August day when the garden was clotted with raspberries and zinnias, poppies and Michaelmas daisies whose blooms were wide as saucers. I was coming back from Halifax and the kind of contentious stockholders' meeting that sets one to wondering how early man ever found his way out of the cave, and why, considering his natural tendencies, he didn't stay there, when on impulse I drove over the long, curving causeway connecting Moose Island with the U.S. mainland.

I bought my lunch of a sandwich and coffee at the IGA, and walked all over town before sitting down on the green-painted front steps of a big old white house whose bare windows showed a shimmeringly vacant interior. In front of the house I stood on tiptoe and peered in, watching a patch of sunshine move slowly across a pale maple floor that was badly in need of refinishing. Someone had torn the carpeting down from the stairs; the risers looked wormy with old nail holes.

I noted with surprise how certain I felt, how calm. Later I found my way to a tiny storefront real-estate office on Water Street, overlooking Passamaquoddy Bay, and that evening when I drove back to the mainland, the house belonged to me.

What were you thinking of? my ex-husband asked, and so did my relatives and friends. Even my son Sam looked doubtful, although at sixteen he had begun looking doubtful about everything. With a brain surgeon for a father and a money expert for a mother, he was unhappily aware of the problem of living up to all the brilliant genes he had supposedly inherited.

The trouble was, Sam's brains were not of the quick, flashy variety so popular with Ivy League admissions committees. He was the type who could take one look at a broken washing machine, come back from the appliance store with a part that cost five dollars, and a little while later the washing machine would be fixed. He could do the same with an ailing cat, or the gizmo that makes (or doesn't make) a doorbell ring. What he couldn't do was explain how to fix the washing machine, or what sort of attention to give the cat; his perceptions were visceral and immediate, not filtered by words and numbers. They weren't particularly quantifiable, either, unless you happened to have a broken washing machine.

Which is to say that despite every effort of mine, he was flunking out of school, and so angry about it that he had turned to a group of similarly estranged young outlaws, each with a bad attitude and a ready supply of marijuana, and I was worried about him.

"Just come and look at the place," I said. "Will you do that? And if you don't want to, you don't have to stay."

"Yeah, right," he muttered. "Like I can go and live with Dr. Doom."

That was what he had taken to calling his father, on account of the dismal prognosis of most of his father's patients; my ex-husband's operating room is a sort of last-chance hotel for the neurologically demolished.

"Dr. Doom," I told my son, "would be delighted to have you." Over my dead body, I thought but did not say. Sam's father is a charming fellow when he wants to be, but too many years inside other people's heads have convinced him that he is an authority on all that goes on there.

Which he is not. When it comes to the sport of human beingness, my ex-husband knows the rules but not the game, and it is never his blood on the playing field. After six months in the presence of his superachieving father, nothing would be left of Sam but a little pile of bones and hair.

"But that won't be necessary," I told Sam, "because if you don't like Eastport, I'm not going there, either."

Then I held my breath for three days: one while we drove up Route 1 through Bucksport and Bar Harbor and 1A through Milbridge toward Machias, and two more while Sam auditioned Eastport. He explored Wadsworth's hardware store, and pronounced its nuts-and-bolts selection adequate. He stood on the wharves where the cargo ships come in, the massive vessels looking as incongruous as twenty-story buildings plunked down in the midst of the tiny fishing village. He sat on the bluffs overlooking the whirlpool, Old Sow--the largest whirlpool in the Western Hemisphere--and watched the diurnal tide rise its customary twenty-eight feet, which is nine-point-two inches every ten minutes.

During this time I did not smell marijuana, nor did I see the unhappy look I had grown accustomed to back in the city: the look of a boy with a dozen extraordinary talents, none of them valued or even recognized on Madison Avenue, and by extension not in the rest of the world either, because their possessor was unlikely to earn enough money to buy a lot of expensive products.

On the fourth morning I found him sitting at the oilcloth-covered table, in the big old barnlike kitchen with the tall maple wainscoting and the high, brilliant windows. He was drinking a cup of coffee and looking at a set of papers, registration forms for the upcoming year at Shead High School. Carefully, in the labored but rigorously correct block printing that, at age ten, he had finally managed to master, Sam had filled in all the spaces except one.

Parent's signature, the line read. "I think," Sam said, "that you should sign this." So I did.

And that, as they say, has made all the difference.

Coming upon a body is an experience, like childbirth or a head-on collision, that takes the breath out of a person. I went back through the passageway between the kitchen and the small, unheated room where in spring I kept dog food and dahlia bulbs, and where apparently I now stored corpses.

"Ellie," I said, "there's a dead man out there on the floor."

Ellie White looked up from the kitchen workbench where she was planting pepper seeds, sprinkling a few into each little soil-filled peat pot, to be set out later in the cold frame. Ellie has coppery hair cut short around a thin, serious face lightly dusted with freckles; her pale blue eyes are so intense that even through her glasses, her gaze makes you feel your X-ray is being taken.

Her index finger paused in the act of tamping soil onto a pepper seed. "Who?" she asked.

Sometimes I think Ellie has formaldehyde in her veins. For instance, when I moved to Maine I thought sill work meant painting them, and if you have ever restored an elderly house you will understand the depths of my innocence; sill work is slightly less radical than tearing the house down and starting over entirely, and almost as expensive, and if you don't do it the old house ends up at the bottom of the cellar-hole.

Ellie, upon hearing that this was what my old house needed, merely remarked how lucky I was that I could pay for it, because she knew of another woman whose house had needed sill work, too, and that woman was now living in the cellar-hole. Ellie's comment shut me up pretty quickly, as she had intended, and I resigned myself to getting the job done in spring, but along about March I'd discovered that sill work was only the beginning. There was also the poignant little problem of the rot-raddled floor joists, and of the support beams holding up the floor joists.

Or rather, not holding them up. "I don't know who. He's lying facedown in the corner where everything sags. I should have had that floor jacked up last autumn."

Ellie was wearing denim coveralls, a bright yellow turtleneck with jade-green turtles satin-stitched onto it, and shiny green gardening clogs over thick, yellow socks. On anyone else the outfit would have been hilarious, but Ellie is so tall and slender that she could wear a painter's drop cloth, possibly with a couple of frayed dishrags belted around it, and still look just like a Paris runway model.

"I don't think the floor is the issue here," she said.

"That's because it's not your floor. The only thing holding that floor up now is habit, and when the homicide detectives and the medical examiner and I don't know who all else start tramping in and out of there, then that floor is going to ..."

She was looking at me as if I'd just arrived from Mars. "Jacobia," she said, "I don't know what kind of law enforcement you got used to, back in the big city where you come from."

She picked up the telephone, dialed George Valentine's number, and let it ring. "But in case you haven't noticed, you're not in New York anymore. You're in Eastport, Maine, three hours from Bangor and a heck of a lot farther from anywhere else, and the only person tramping in and out of that storeroom is going to be George. That is, if he ever answers his phone. He was over at my house earlier, but I don't know where he is now."

Of course it was George's number. In Eastport, George was it: if you had a fire, or a flood, or a skunk in the crawlspace, George was the man you wanted, which was lucky since the rest were out on fishing boats: dragging for scallops, hauling lobster pots, or collecting sea urchins, depending upon the season.

"I'm going out there," Ellie said, after George had picked up at last and promised to be right over.

People in Eastport do not think the telephone grows naturally out of the tympanic membrane, and some of them will actually decide whether to answer it or not based on what sort of news they are expecting. But George always answered his telephone sooner or later on account of being the clam warden, on call to make sure diggers had valid clam licenses, chase poachers out of forbidden clam areas, and spot-check the clams themselves with his two-inch metal claim ring, through which a legally harvestable bivalve must not be able to pass.

"I think," Ellie added, "we should make sure the man is really dead."

This struck me as pointless, since an ice pick in the cranium promised little in the way of future prospects. But Ellie was determined; it was part of her downeast Maine heritage, like being able to navigate in the fog or knowing how to dress out a deer.

"It might be he's only wounded," Ellie said. "It might be we can still do something for him."

Right, and it might be that next we could multiply some loaves and fishes. When she had gone I ran a glass of water and stood there by the sink, pondering whether to drink it or not. Just breathing in and out suddenly seemed to require a series of massive, separately considered decisions, as if each small action of mine had abruptly become huge compared to all the ones the dead man was not taking.

Outside my kitchen window a flock of cedar waxwings descended on the crabapple tree and began devouring frozen fruit, their short, metallic cries creating a happy clamor. A shower of snow as fine as salt fell around them, whitening the snow already lying on the ground, so their lime-green feathers and candy-corn beaks stood out as brightly as paint drops.

Down at the breakwater, the big ship Star Verlanger sounded her massive horn and cast off, loaded with paper pulp, and the dockworkers jumped in their pickup trucks and headed for a well-earned bottle of Narragansett beer, no bottle of which the dead man would be enjoying. I wondered if his absence would be noticed, or if he was from away. Whichever; by tonight, news of his death would be all over town.

That was what I thought when the whole thing began. But back then, I didn't know the half of it.

* * *

My name is Jacobia Tiptree, and my ex-husband says I am insane. I have proved this, he says, by giving up a perfectly charming little townhouse on the upper east side of Manhattan--complete with doorman, elevator, and building superintendent--for a huge antique structure every centimeter of which needs paint, plaster, or the underpinnings required to hold up both. The roof leaks, the gutters dangle, and the bricks in the chimneys are quietly turning to sand; when the wind blows hard, which it does very often here, the windows rattle as if they are trying to jump out of their frames, and if you put a marble down on the kitchen floor it will probably roll forever.

I found the place on a warm August day when the garden was clotted with raspberries and zinnias, poppies and Michaelmas daisies whose blooms were wide as saucers. I was coming back from Halifax and the kind of contentious stockholders' meeting that sets one to wondering how early man ever found his way out of the cave, and why, considering his natural tendencies, he didn't stay there, when on impulse I drove over the long, curving causeway connecting Moose Island with the U.S. mainland.

I bought my lunch of a sandwich and coffee at the IGA, and walked all over town before sitting down on the green-painted front steps of a big old white house whose bare windows showed a shimmeringly vacant interior. In front of the house I stood on tiptoe and peered in, watching a patch of sunshine move slowly across a pale maple floor that was badly in need of refinishing. Someone had torn the carpeting down from the stairs; the risers looked wormy with old nail holes.

I noted with surprise how certain I felt, how calm. Later I found my way to a tiny storefront real-estate office on Water Street, overlooking Passamaquoddy Bay, and that evening when I drove back to the mainland, the house belonged to me.

What were you thinking of? my ex-husband asked, and so did my relatives and friends. Even my son Sam looked doubtful, although at sixteen he had begun looking doubtful about everything. With a brain surgeon for a father and a money expert for a mother, he was unhappily aware of the problem of living up to all the brilliant genes he had supposedly inherited.

The trouble was, Sam's brains were not of the quick, flashy variety so popular with Ivy League admissions committees. He was the type who could take one look at a broken washing machine, come back from the appliance store with a part that cost five dollars, and a little while later the washing machine would be fixed. He could do the same with an ailing cat, or the gizmo that makes (or doesn't make) a doorbell ring. What he couldn't do was explain how to fix the washing machine, or what sort of attention to give the cat; his perceptions were visceral and immediate, not filtered by words and numbers. They weren't particularly quantifiable, either, unless you happened to have a broken washing machine.

Which is to say that despite every effort of mine, he was flunking out of school, and so angry about it that he had turned to a group of similarly estranged young outlaws, each with a bad attitude and a ready supply of marijuana, and I was worried about him.

"Just come and look at the place," I said. "Will you do that? And if you don't want to, you don't have to stay."

"Yeah, right," he muttered. "Like I can go and live with Dr. Doom."

That was what he had taken to calling his father, on account of the dismal prognosis of most of his father's patients; my ex-husband's operating room is a sort of last-chance hotel for the neurologically demolished.

"Dr. Doom," I told my son, "would be delighted to have you." Over my dead body, I thought but did not say. Sam's father is a charming fellow when he wants to be, but too many years inside other people's heads have convinced him that he is an authority on all that goes on there.

Which he is not. When it comes to the sport of human beingness, my ex-husband knows the rules but not the game, and it is never his blood on the playing field. After six months in the presence of his superachieving father, nothing would be left of Sam but a little pile of bones and hair.

"But that won't be necessary," I told Sam, "because if you don't like Eastport, I'm not going there, either."

Then I held my breath for three days: one while we drove up Route 1 through Bucksport and Bar Harbor and 1A through Milbridge toward Machias, and two more while Sam auditioned Eastport. He explored Wadsworth's hardware store, and pronounced its nuts-and-bolts selection adequate. He stood on the wharves where the cargo ships come in, the massive vessels looking as incongruous as twenty-story buildings plunked down in the midst of the tiny fishing village. He sat on the bluffs overlooking the whirlpool, Old Sow--the largest whirlpool in the Western Hemisphere--and watched the diurnal tide rise its customary twenty-eight feet, which is nine-point-two inches every ten minutes.

During this time I did not smell marijuana, nor did I see the unhappy look I had grown accustomed to back in the city: the look of a boy with a dozen extraordinary talents, none of them valued or even recognized on Madison Avenue, and by extension not in the rest of the world either, because their possessor was unlikely to earn enough money to buy a lot of expensive products.

On the fourth morning I found him sitting at the oilcloth-covered table, in the big old barnlike kitchen with the tall maple wainscoting and the high, brilliant windows. He was drinking a cup of coffee and looking at a set of papers, registration forms for the upcoming year at Shead High School. Carefully, in the labored but rigorously correct block printing that, at age ten, he had finally managed to master, Sam had filled in all the spaces except one.

Parent's signature, the line read. "I think," Sam said, "that you should sign this." So I did.

And that, as they say, has made all the difference.

Recenzii

"No cozy this, it's amusing, cynical, yet warm, populated with nice and nasty characters and some dirty secrets...All the ingredients fit the dish of delicious crime chowder."—Booknews from The Poisoned Pen

"In her polished debut, Graves blends charming, evocative digressions about life in Eastport with an intricate plot, well-drawn characters and a wry sense of humor."—Publishers Weekly

"In her polished debut, Graves blends charming, evocative digressions about life in Eastport with an intricate plot, well-drawn characters and a wry sense of humor."—Publishers Weekly

Descriere

Jacobia "Jake" Tiptree left her investment job in New York to remodel a 200-year-old home is Eastport, Maine. But she has scarcely begun to spackle when she wonders if her new life is any improvement on her old: there's a dead body in her storeroom. Now, Jake must crack the identity of a cold-blooded killer--and still make time for lobster culling and home improvement.