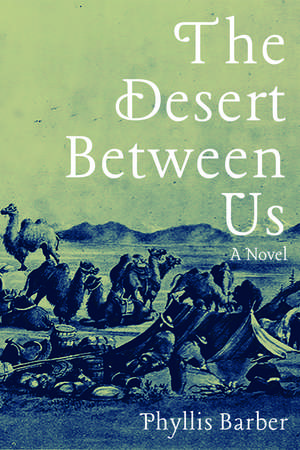

The Desert Between Us: A Novel: Western Literature and Fiction Series, cartea 1

Autor Phyllis Barberen Limba Engleză Hardback – 14 apr 2020 – vârsta ani

2020 Association for Morman Letters Finalist, Fiction

The Desert Between Us is a sweeping, multi-layered novel based on the U.S. government’s decision to open more routes to California during the Gold Rush. To help navigate this waterless, largely unexplored territory, the War Department imported seventy-five camels from the Middle East to help traverse the brutal terrain that was murderous on other livestock.

Geoffrey Scott, one of the roadbuilders, decides to venture north to discover new opportunities in the opening of the American West when he—and the camels—are no longer needed. Geoffrey arrives in St. Thomas, Nevada, a polygamous settlement caught up in territorial fights over boundaries and new taxation. There, he falls in love with Sophia Hughes, a hatmaker obsessed with beauty and the third wife of a polygamist. Geoffrey believes Sophia wants to be free of polygamy and go away with him to a better life, but Sophia’s motivations are not so easily understood. She had become committed to Mormon beliefs in England and had moved to Utah Territory to assuage her spiritual needs.

The death of Sophia’s child and her illicit relationship with Geoffrey generate a complex nexus where her new love for Geoffrey competes with societal expectations and a rugged West seeking domesticity. When faced with the opportunity to move away from her polygamist husband and her tumultuous life in St. Thomas, Sophia becomes tormented by a life-changing decision she must face alone.

Din seria Western Literature and Fiction Series

-

Preț: 163.72 lei

Preț: 163.72 lei -

Preț: 167.85 lei

Preț: 167.85 lei -

Preț: 331.46 lei

Preț: 331.46 lei - 21%

Preț: 88.08 lei

Preț: 88.08 lei - 18%

Preț: 104.79 lei

Preț: 104.79 lei -

Preț: 117.99 lei

Preț: 117.99 lei - 18%

Preț: 98.53 lei

Preț: 98.53 lei - 20%

Preț: 164.26 lei

Preț: 164.26 lei - 23%

Preț: 125.71 lei

Preț: 125.71 lei -

Preț: 142.46 lei

Preț: 142.46 lei -

Preț: 233.30 lei

Preț: 233.30 lei - 21%

Preț: 130.17 lei

Preț: 130.17 lei - 21%

Preț: 123.98 lei

Preț: 123.98 lei - 20%

Preț: 150.68 lei

Preț: 150.68 lei - 22%

Preț: 119.64 lei

Preț: 119.64 lei - 18%

Preț: 272.73 lei

Preț: 272.73 lei -

Preț: 143.57 lei

Preț: 143.57 lei - 19%

Preț: 191.23 lei

Preț: 191.23 lei - 20%

Preț: 164.26 lei

Preț: 164.26 lei -

Preț: 93.51 lei

Preț: 93.51 lei - 20%

Preț: 166.23 lei

Preț: 166.23 lei - 23%

Preț: 119.01 lei

Preț: 119.01 lei - 17%

Preț: 98.97 lei

Preț: 98.97 lei - 19%

Preț: 170.12 lei

Preț: 170.12 lei - 22%

Preț: 141.09 lei

Preț: 141.09 lei - 19%

Preț: 160.50 lei

Preț: 160.50 lei -

Preț: 130.42 lei

Preț: 130.42 lei -

Preț: 97.51 lei

Preț: 97.51 lei - 22%

Preț: 119.64 lei

Preț: 119.64 lei - 21%

Preț: 88.18 lei

Preț: 88.18 lei - 23%

Preț: 119.27 lei

Preț: 119.27 lei -

Preț: 84.93 lei

Preț: 84.93 lei -

Preț: 120.25 lei

Preț: 120.25 lei - 22%

Preț: 141.89 lei

Preț: 141.89 lei - 22%

Preț: 134.99 lei

Preț: 134.99 lei - 23%

Preț: 118.47 lei

Preț: 118.47 lei -

Preț: 137.36 lei

Preț: 137.36 lei - 22%

Preț: 133.67 lei

Preț: 133.67 lei - 21%

Preț: 149.88 lei

Preț: 149.88 lei -

Preț: 246.99 lei

Preț: 246.99 lei - 18%

Preț: 204.11 lei

Preț: 204.11 lei - 21%

Preț: 88.00 lei

Preț: 88.00 lei -

Preț: 199.71 lei

Preț: 199.71 lei - 19%

Preț: 167.92 lei

Preț: 167.92 lei -

Preț: 196.25 lei

Preț: 196.25 lei - 22%

Preț: 147.87 lei

Preț: 147.87 lei -

Preț: 110.49 lei

Preț: 110.49 lei - 21%

Preț: 143.29 lei

Preț: 143.29 lei - 21%

Preț: 136.41 lei

Preț: 136.41 lei - 21%

Preț: 183.48 lei

Preț: 183.48 lei

Preț: 260.64 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 391

Preț estimativ în valută:

49.89€ • 51.88$ • 41.80£

49.89€ • 51.88$ • 41.80£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781948908566

ISBN-10: 1948908565

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.64 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: University of Nevada Press

Colecția University of Nevada Press

Seria Western Literature and Fiction Series

ISBN-10: 1948908565

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.64 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: University of Nevada Press

Colecția University of Nevada Press

Seria Western Literature and Fiction Series

Recenzii

"A historical love story about the American West and the need for human connections... Most appealing for the scenery it captures, the book devotes paragraphs to the magnificence of the Nevada countryside. It captures big skies and scorching deserts as its characters wage an unwinnable struggle against nature. A subplot related to the real-life introduction of Arabian camels to the American Southwest involves considerable detail about how the plan worked—and didn’t. The book’s intentional fusion of the culture of the American West with the desert life of the Arabian Peninsula is a point of interest."

—Foreword Reviews

Barber’s exquisite prose captures the beauty and the grandeur of the arid red rock country as well as Sophia’s longing for human connection and her struggle with duty and desire. Geoffrey Scott reminds her of how love can change a person and her world, and the camel takes it all in, placidly watching—as immovable as the desert.

—Michele Morris, author of The Cowboy Life

The Desert Between Us tells a unique story about a small corner of American history which hasn’t had much light shed on it—and it involves a camel in the American West and The Great Wagon Road origins of Route 66, no less! Phyllis Barber’s words are poetry, and she deftly conveys the hopes and yearnings of a young Englishwoman who has joined the Mormons in Utah, entered into a polygamous marriage, and then finds herself transplanted hundreds of miles away to a small and inhospitable settlement in the desert. Her struggle to keep her young idealism healthy and vibrant in the dry, unforgiving desert is soul-stirring. It is a story of love and passions that are sometimes in conflict with a strong sense of duty and commitment to a larger cause. Phyllis Barber manages to convey the fragile and delicate beauty of the desert landscape in a manner that is evocative and transcendent, and then contrasts that beauty with the harshness and despair of that forbidding land.

—Kathy Gold, artist

—Foreword Reviews

Barber’s exquisite prose captures the beauty and the grandeur of the arid red rock country as well as Sophia’s longing for human connection and her struggle with duty and desire. Geoffrey Scott reminds her of how love can change a person and her world, and the camel takes it all in, placidly watching—as immovable as the desert.

—Michele Morris, author of The Cowboy Life

The Desert Between Us tells a unique story about a small corner of American history which hasn’t had much light shed on it—and it involves a camel in the American West and The Great Wagon Road origins of Route 66, no less! Phyllis Barber’s words are poetry, and she deftly conveys the hopes and yearnings of a young Englishwoman who has joined the Mormons in Utah, entered into a polygamous marriage, and then finds herself transplanted hundreds of miles away to a small and inhospitable settlement in the desert. Her struggle to keep her young idealism healthy and vibrant in the dry, unforgiving desert is soul-stirring. It is a story of love and passions that are sometimes in conflict with a strong sense of duty and commitment to a larger cause. Phyllis Barber manages to convey the fragile and delicate beauty of the desert landscape in a manner that is evocative and transcendent, and then contrasts that beauty with the harshness and despair of that forbidding land.

—Kathy Gold, artist

Notă biografică

Phyllis Barber is an award-winning author of nine books, including Raw Edges and How I Got Cultured, and winner of the AWP Prize for Creative Nonfiction. She has received awards for both her fiction and nonfiction and has published essays and short stories in North American Review, Crazyhorse, and Kenyon Review. She has been cited as Notable in The Best American Essays and in The Best American Travel Writing. In 2005, Barber was inducted into the Nevada Writers’ Hall of Fame. She lives in Park City, Utah.

Extras

CHAPTER ONE: THE VISIONS

AUGUST 1867

Geoffrey Scott does a double take. Is that what he thinks it is?

He’s left Fort Mojave behind—buildings, stockade, new fence—and wandered into the desert to the tune of a few cicadas repeating their crrr-ing call. The night is lit by a fingernail moon and more stars than he’s ever seen before. Millions. Billions. But there’s an outline against the night sky. A bizarre repeat of something he’s seen before. Head raised high. The hump of a back and the arch of a neck accentuated by moonlight. That silhouette looks like Attah Allah standing in an outcropping of rocks but looking more like the carving of an animal king looking down from a high place. Tonight it’s not foraging. Perfectly still against the backdrop of a starry sky in its kingdom of sand and bush.

It takes a few steps. Geoffrey Scott takes his chances.

“Adababa,” he yells into an almost empty desert.

No sound. No answer.

But now he’s sure. That silhouette is the camel he rode next to on the first expedition from Texas. The one he’d ridden to the Colorado River to get supplies to Beale. Untethered, unhobbled, and uncoralled. The Civil War’s over and Jefferson Davis, the main honcho for bringing the camels stateside, well, he’s gone. What a joke. But what’s Adababa doing here? Tonight?

Geoffrey Scott feels a sharp wind cooling his backside. He lifts his shoulders as high as they’ll go, rotates them backward and forward to ease the stiffness, then reaches for the thin roll of blanket tucked into his pack. What does this all mean, he wonders, then shakes himself from the allure of pies in the sky. He’d better get the animal back to the fort where it belongs.

Tossing the blanket over his shoulders, he stumbles through the scattered rocks and approaches the camel. He shakes his head. Frustrated. When he looks closely, he sees that no one has tended to the animal’s well-being.

“Hi there, Baba. What you doing out here, no hobbles on your feet? You run away?” Adababa nuzzles into his shoulder and groans, a familiar sound Geoffrey Scott’s heard before.

The army’s been careful with their valued cargo from the Levant, even brought their own handler with them over the high seas—Hadji Ali, the man who’d taught Geoffrey Scott how to get a camel to do what a man wanted, something most of the military never bothered learning. Few soldiers are interested in the camels or their handler—a man who speaks foreign gibberish, they say. A believer in Mohammet.

Geoffrey Scott’s glad he never signed up for the uniform. Never wanted to. The idea never settled well with his Congregational/Abolitionist sensibilities anyway. Thank the Lord Above he knew how to build things. Keep himself employed and away from the enlistment office, but uniform or no, he’s helped carve the Great Wagon Road out of his bone and blood. Under Lieutenant Beale. A military road even if most of the builders were just plain working men. An accomplishment not small in anyone’s memory. Then he’s hung around Fort Mojave to help build its walls and repair its leaks. But now, as of last week, the government’s claimed the Mojave’s land. Told the tribe who knows best. He’s had enough.

He takes a long look at Adababa—alone in the desert, free as a wild animal and yet not wild. No one’s tending him. No hobbles. No broken rope around his neck. Property of the U.S. Government even if soldiers’ve been pushing some of the camels over cliffs. Favor their horses. Put off by exotic animals. But he knows this particular one. He’s ridden on its back: ten feet tall when his head’s straight in the air, about nine feet long and five feet wide, probably a ton. A camel can outlast and outpack any horse or mule in the Mojave Desert. Adababa’s his camel as much as anyone’s.

Geoffrey Scott scratches his nose with the back of his hand. Impulsively, he decides. He and Adababa will head north. Together. On the Old Spanish Trail which the Mormons have turned into the Salt Lake Road. Look for that salt mine Kwami’s told him about. Find pieces as big as a man’s fist. Pure, clear, more valuable than diamonds. People will pay for salt. That’s what this night is all about. This camel. This vision. God’s gift indeed.

* * * * *

The crescent moon. One side of a parentheses, he laughs to himself. A future open to him. Geoffrey Scott from Osawatomie, Kansas, reaches over his shoulder and pats himself on the back. He has a partner now. A camel. He’s about to become something more important than he’s been. He smiles, the full moon itself. Too bad his mother isn’t alive to see this. Then he shuts his eyes to escape the memory of blood haloing her head, pooling on the slats of the porch in Kansas, her stillness.

Wherever the souls of his parents are, he’ll make them proud, though he’d best not forget his father scoffing at pride. That man never had hopes—high or low—pushing his only son out the door when his mother was killed. How he, Geoffrey Scott, came to be, he’ll never figure because that coupling was unimaginable. He never saw tenderness of any kind. Or nakedness. Those parents had moved to Kansas from Massachusetts to cultivate fertile land, to live wide-open, and to help protect the territory from the spread of slavery. But then, something called Bleeding Kansas happened. Porous borders with Missouri. Slavers who hated anti-slavers. Slavers with their shotguns and their moonshine. His mother said no good-bye at all. She’d been so kind to everybody, no matter who. Even to his cantankerous father—the man he both loved and feared. He could still hear the man’s crazy talk in his head.

He ties Adababa to a bush with a long rope from his pack, uncoils the horse whip he’s carried from Kansas, and forms it into a circle on the sand. He takes his blanket off his shoulders and lays it inside. Snakes won’t cross that line.

While Geoffrey Scott sleeps, dreaming about salt mines and the people who’ll pay top dollar, Adababa eats the first, the second, then all the branches on the bush to which he’s tied, mashing the brambles and thorns in its teeth. Then the camel wanders into the desert, snaking the line tied to his neck, forming a myriad of sand patterns, unmindful of his business partner sleeping inside the circle of rope. He grazes from bush to bush, from yucca spike to creosote leaves, and then stands still as a statue on another hill—this time for the eyes of Kwanyumai, the Mojave, who never sleeps by the fort at night even though he walks and hammers on its rising walls by day. Geoffrey Scott came across him about three years ago. On the other side of the river. Gave him yellow medicine for his chills and shivering.

But tonight, the stars are legion. The sky is alive. Kwami is alone, unseen by Geoffrey Scott. The camel strolls into the night with no invitation or no capture—Attah Allah, as the Arab has taught Geoffrey Scott and as he has taught Kwami. God’s gift. The Indian, if he spoke of such things, would use other words and say the camel is a gift from Mutavilya. Alone on the hilltop, the animal must have come for Mutavilya’s reasons. Kwami moves quietly through the night, his moccasins soft in the sand, then catches hold of the rope hanging loose from Adababa’s halter. He reaches up and rubs the side of the camel’s nose with two fingers. Good animal. Strong. Taller than Kwami. Almost two Kwamis for one Adababa. Together, they walk toward a shallow cave where the Mojave hobbles the camel by his side. This camel belongs to him now. It is a gift. He rolls into his own blanket and closes his eyes for the night, all of this while Geoffrey Scott tosses in his own bedroll, dreaming of Adababa close by.

* * * * *

Rising before the sun, Geoffrey Scott witnesses the emptiness. He panics and coils his rope and whip, tucks them into his saddlebag, and follows the trail left by the camel and the rope. At first, he only sees the unusual footprints and snaky imprint of the dragging rope, but then there are human tracks to the side. Over rocks and mesquite, Geoffrey Scott follows these prints to the cave of red sandstone, which is more indentation than cave—a windbreak. On a bed of sand cradled next to a rising wall of striated sandstone, he sees Kwami wrapped in a blanket, his long black hair freed from its usual band of deer leather and fanned out across his cheek. Adababa dozes beside him, his legs stretched in front and a rope tied around his back hooves.

The light of dawn works its fingers through the myriad of rock formations, the deep shadows paling to an indistinct gray. Geoffrey Scott finds a long branch to tease the black hair away from Kwami’s cheek.

“Wake up, you lazy Injun.”

Kwami wakes. He’s startled to see Geoffrey Scott standing there, so far away from Fort Mojave where they usually meet.

“What are you doing with my camel?” Geoffrey Scott asks.

“He comes to me,” Kwami says. “Last night.”

“You got it wrong. He came to me.”

“No. To me. His shadow against the moon.”

There is no arguing with Kwanyumai’s certainty, but Geoffrey Scott believes the Indian doesn’t understand the order of things. “You don’t believe in ownership anyways. I had him first.” Chin talk.

“I did.” Raised-fist talk.

Adababa remains seated, unable to rise with the hobbles on his back legs. His luxurious eyebrows magnify the handsomeness of his face, long, thick eyelashes brushing the air, opening and closing. Looking wise, impartial, and imperial.

“I could shoot you.” Geoffrey Scott puts his hand on his gun which has never been aimed at a human being or animal even. “But then,” he tempers his initial impulse and folds his arms. His bravado turns to gest. He laughs. “I guess you could pierce my side with an arrow.” He points to Kwami’s quiver and the arrows bundled inside. “Where’s this argument leading anyway?”

Something diffuses between them. The anger dies a simple death. Maybe because the two men are friends. They’ve been learning each other’s language back at the fort.

“We’ll be business partners,” Geoffrey Scott says. “How about that?” He offers his hand, though he isn’t sure Kwami understands business the same way he does. He isn’t sure if his deal with Kwami can be decided with a handshake.

And Kwami, on his part, keeps close watch on Geoffrey Scott and Adababa, as if he’s making sure neither of them goes too far away. Mr. Scott is not a man of Kwami’s tribe, after all. He has light eyes and strange skin. And the camel has been given to him by Mutavilya.

SEPTEMBER

“You better make yourself scarce,” Geoffrey Scott says to Kwami, the river roaring in the background. “Your kind’s not too popular around here.”

Kwami ignores him, squatting, tossing rocks into the roiling current. Fast. Savage. Powerful. He seems spellbound by the river.

“Hey. You hear me? You better get while the getting is good.”

No response, only another rock sailing through the air and disappearing into the fast-running water.

The canyon walls are pressing tighter here. The river’s grown preposterously huge arms to wrestle the channel making its way south. Broad. Brackish. Red with sands picked up along the way, turning over and over, red sand rolling.

Geoffrey Scott knots the rope attached to Adababa’s halter and takes a long look at the ferry that crosses the river. Hardy’s Landing—a hefty line of woven hemp stretched across and a flat-bottomed boat waiting on the other bank. But then, suddenly, Adababa spits, startling both Geoffrey Scott and Kwami. Then the camel turns and twists as if it’s swallowed a jumping bean.

“Whoa,” Kwami shouts and jumps to full height. Then, he pulls his shoulders down and rolls his head around to straighten it. “Baba,” he says in a low voice. “You don’t spit.”

Geoffrey Scott tries to stroke the camel’s neck, hoping to calm the nervous animal, but Adababa’s acting like the water is an enemy, maybe remembering the way it swept the horses downstream the time they all crossed. It skitters sideways, then spits again and swings its neck, threatening Geoffrey Scott because it could crush him against a rock and squeeze the life out in not much time. Adababa’s one perturbed, unpredictable camel that could crush him against a rock and squeeze the life out in not much time.

Kwami quietly works his way to the camel’s side and reaches out to squeeze its thigh gently. Then, best as he can, he strokes the camel’s neck. It’s riled up big time, showing another side of itself the two men have never seen before.

“Settle down, Baba,” says Geoffrey Scott, jumping back to keep his distance from the kicking hooves. “We’re not crossing this beast today. When’d you start spitting and kicking anyway?”

Adababa turns its back on the water and on Geoffrey Scott, pulling on the rope and prancing angrily on its dinner-plate hooves.

“Temperamental thing, aren’t you now?” Geoffrey Scott says. Adababa keeps overworking his tether. Deaf to any reason except his own.

“It won’t do you any good to be ornery.” Geoffrey Scott holds tight in this seesaw battle.

Kwami steps closer, then puts both of his large hands on the animal’s side and mouths a few words, indiscernible to Geoffrey Scott. Maybe some Indian words. Some chant to remind Adababa he’s among friends. Gradually Adababa settles, not yanking the rope so hard.

“That was a tantrum,” Geoffrey Scott says to the camel who’s now chewing on the branch of a tamarisk as if nothing had happened, a committed sampler of anything with leaves. “Hey. Kwami. You ever seen Baba like this?”

Kwami shakes his head then walks back to the edge of the river and squats.

“Easy for you to say now he’s calmed,” Geoffrey Scott calls after him, envious of the nonchalance of the man.

“Adababa understands. My words. We are like brothers.”

Geoffrey Scott thinks he hears what Kwami is saying, but there’s too much background noise from the river. Maybe Kwami thinks Adababa’s more in tune with him for some reason. Foolish thinking. He looks back to the river and squints his eyes at the narrowing of the canyon. The Colorado is large. Humbling. Domineering in a land of mountains of stacked, dried mud and valleys of rock and dirt. Kwami seems to be listening to the subterranean roar of water over rocks—the unseeable forces submerged. “Aha Kwahwat,” the Indian says out loud, as if the water’s a fire that needs close watching.

“Colorado. The Red River,” Geoffrey Scott says, smiling, tilting his head back, and proud of the fact he’s speaking both Spanish and English. Kwami, however, seems more interested in the water. But no matter how big the Indian is, Geoffrey Scott thinks, he’s still diminutive next to that big-ass camel that could hurt a body if it had a mind to. Wouldn’t want to be on the wrong side of the fence when that animal’s ire is up and running. But then he wonders again about Kwami who seems to understand the animal better than Geoffrey Scott does even though he doesn’t believe that for one minute.

When they’d first met, the Indian had been shaking like a leaf. Pitiful with ague. After the medicine and more than one painful grimace, the Indian wrapped himself in the blanket Geoffrey Scott had given him and sat by the fire into the night. A year later, Kwami appeared again, the same man, but this time a painted warrior dressed in loincloth and war bonnet, pointing an arrow at Adababa’s heart while it carried Geoffrey Scott to get supplies to Lieutenant Beale stranded on the other side of the river. Both of them could have died then. No more pulse. Heartbeat. Nothing. Painted men running in every direction, the situation a mad scramble. And now, he’s squatting next to the river, quietly contemplating its fury, maybe even its blessings before the three head north. How his father would have loved the irony: the son of an abolitionist, a camel, and a Mojave Indian.

“Time for you to skedaddle,” he says. He looks carefully up and down the banks, wary someone might be watching him talking to a red man which was trouble to most minds. “Get yourself out of here. Now.” He hands the rope to Kwami.

Kwami starts climbing with Adababa, but then turns his head back and points to the cliffs. “Mojaves know secret places in rocks.”

Somewhere, in the myriad of chats he’s had, Geoffrey Scott’s heard of a rocky labyrinth near the river carved out by the Indians. How the natives scramble over tortured rocks, tunnel through, negotiate this cobweb to travel from south to north. Hiding from those tribes that would pursue them or seeking shade in this hostile land. But this is the first time he’s heard mention from Kwami. “You know about those?”

“Some.”

“Would Adababa fit?”

“Some.”

Kwami starts to climb again, Adababa behind him. He never smiles, and in this way reminds Geoffrey Scott of the very wooden Indian someone had carved and placed at the temporary entrance to the fort—a cockeyed notion of a red man. Kwami is silent most of the time, though Geoffrey Scott knows him for more than this. If there were such a thing as blue ribbons given out in a competition for learning English, Kwami would win. By a long shot.

“Time to be gone, you two.”

The Indian pulls Adababa carefully by the rope around its neck. “Follow your master, Baba.”

“Master?” though Kwami is beyond hearing his response. Geoffrey Scott can’t believe what he’s just heard. “You gotta be joking with that one.” Then he shouts. “I need to get more information about where we’re going. Take care with Adababa’s feet. He’s been complaining.”

Never mind what Kwami thinks, he says as he trudges off to Hardy’s Landing, sinking below the surface in the unreliable sand, some of it filling with water after he steps, but he’s glad his companions are headed where they’ll be invisible. Somebody could ask questions. The camel’s a circus, hands down. Everyone’s always curious, military or no. “What in the hell’s a camel doing in these parts?” people usually say. And everybody’s frantic about Indians these days. Without those two, Geoffrey Scott might get a good meal. His provisions are smelly from the heat even though Fort Mojave is not that many miles away. But 110+ degrees is too hot for anything. The soles of his once-strong boots are thinning. No one can walk far before they’ll fry like bacon—the sun sizzling skin and bones. The sand a griddle. And rocks. Eternal rocks.

With Adababa’s ability to survive in waterless places and Kwami’s knowledge of the land, he thinks as he negotiates the terrain toward Hardy’s Landing, they might be able to make it through the fire-and-brimstone rocks and cliffs and skirt the worst canyons. Maybe they should take the rough military road he’s heard about. The one carved out by surveyors, boatmen, geologists, engineers—curious types figuring how to get from the Gulf of Mexico upstream. Adababa would do best without rocks, that’s a given. The Old Santa Fe will most likely be best, though he’ll ask at the settlement just ahead, complete with a store, billiard room, dining saloon, a blacksmith, a warehouse, and several houses, or so he’s been told.

After scrambling over a small cliff face, Geoffrey Scott sees a lone man washing clothes. He pulls on his groin, absentmindedly remembering the grains of sand turning his private parts red. Sandpaper in his britches. He pauses and sips the too-hot water in his canteen, careful to ease the scalding liquid over his tongue. It’s September. Indian Summer. Way too hot. The man doing the washing wears no undershirt, his bare feet cooling in the harmless eddy. Geoffrey Scott also sees a soldier on the porch of the main building, this one fanning himself with a military cap, leaning against the adobe wall in a cane chair. No use for discipline in heat that keeps a body from going anywhere or doing anything.

Hacksaw military, Geoffrey Scott thinks to himself. Drifters with nothing else to do. Bludgeons with dull knives trying to be a part of something that’s not anything yet. The whole endeavor trying to get organized though nowhere resembling organization yet. But damn, that Kwam’d be a tough one to round up, so soldiers, don’t get ideas.

The last stretch of sand, damp and deep, requires heavy walking. And heavy thinking. Adababa might be the property of the U.S. military, Geoffrey Scott tells himself, but who cares whether or not the camel’s stolen or discarded property? It’s traveling with us now. And nobody’s going to change that. Me, Kwanyumai, and Adababa are on our own. Not an expedition, military or otherwise. Just a crazy troupe of travelers.

He feels like he’s getting nowhere as his feet sink in the endless sand but nevertheless keeps an eye on the half-dressed soldier nodding off on the front porch. Everything’s slow. Heat like thick molasses. Hot wax. No shade. No escape. Fort Mojave wasn’t like this. Many more soldiers. Lots more activity to protect the military and the emigrants. But it’s no small irony the fort’s been given that name. Replacing the Mojaves like it is. Geoffrey Scott shakes his head and wonders how anyone can tell someone else what they can’t do. Where they can live. What they can eat.

He battles the last few sandy steps and finally reaches the porch of Hardy’s headquarters.

“Howdy,” he says to the soldier who’s half dozing. “Mr. Hardy anywhere around here?”

“Inside.” The man says, then closes his eyes again, not inclined toward conversation of any kind.

Geoffrey Scott climbs the stairs of the main building of Spanish adobe. He opens the door, then hears his footsteps echoing on the red tile floor, the sound larger than the room. Cooler interior, thank God. A relief. More footsteps. A hallway.

Hardy is huddled over a desk in a back office—a man parched and dry from the desert like everyone else who comes here. His face is tanned the color of a kidney bean, almost a dark red, and he wears a battered straw hat that seems more a habit than something to shade him from the unmerciful sun. It’s set back on his head at a tilted angle.

Geoffrey Scott knocks on the half-open door. “Excuse me sir,” he says, pushing the door enough to be seen. “I’m on my way north. Thought you might have some suggestions.”

“I might know a few things,” Mr. Hardy says, half-attentive, thumbing through the papers on his desk. He finally looks up to see who’s talking. “The best advice is to keep goin’. Take the Old Spanish Trail. You can follow the river best you can, but that would be a trial you wouldn’t want.” With his finger that’s been separating paper, Mr. Hardy tips his hat even further away from his face and makes more of an effort. “Bring yourself inside. Couple of settlements north of here. Semi-farmable land, if you’re not afraid of the Mormons. St. Thomas. St. Joe. Mormon towns. Even Callville at the fork of the Muddy and Virgin. Tryin’ to compete with me, think of that, but they’ll never succeed with the river like it is.”

He straightens the few papers into a neat pile. “Keep goin’, young man. Those Mormons are clannish and maybe you won’t get past that. But you might. If that don’t work, there’s a road goes through Las Vegas Meadows into California. Or you can head East to Colorado Territory. Wide open about now. Everybody and California and gold, though the Indians are testier than ever. Watch out for them. Military’s rounding them up where they can be watched. Watch out for them. Trouble. That’s what they are. Think this is their country. We’ll grab them and turn ‘em over to the military if they come here.”

Geoffrey Scott says nothing in response.

“Always hungry. Thieving. Stealing.”

Geoffrey Scott still knows more than he’s hearing and isn’t about to divulge the hiding place of his traveling companions.

“Why don’t you have a bite to eat before you go?”

“Suits me,” he finally answers.

“Got a cook’ll rustle something up for you. Excuse me from joining you. Work to do.”

Questions. Answers. Supplies bought. A hot meal. Over an hour before Geoffrey Scott is climbing the same slope as the camel and Indian had done before him. Looking for his compatriots and hoping Hardy or the soldiers don’t catch sight of Kwanyumai or Adababa passing Hardy’s Landing at the tops of the cliffs, making their way north.

* * * * *

OCTOBER

Geoffrey Scott stands with a pack on his shoulder in what passes as a backyard with its crooked fence of mesquite and leggy creosote. Unknown to him—this man in a dusty cap with an emblem of crossed rifles fastened at the front, this wearer of a pair of nondescript pants and shirt which was crisp and new once upon a time—is interrupting someone’s weekly ritual.

The locusts sing their predictable song, no cloud hovers anywhere in the too-blue sky, and everything loses color in the heat. The heat, its oppression and everywhereness, is strong. He wipes his brow with his much-used handkerchief and stares at this ragtag town. A few mud houses, makeshift tents, and the skeletons of houses to come—signs that the settlement’s working toward respectability. Then his eyes focus on the woman in the yard dressed in a long skirt and soiled blouse. He watches her biting down on the clothespin between her teeth. She wipes the hair from her face and the perspiration from her cheeks.

“Must have been wandering too long,” Geoffrey Scott calls out, touching the brim of his sun-bleached, barely blue hat as he comes closer. “You some kind of vision?”

“YOU are the apparition,” she says, startled, a slightly nervous laugh at the edge of her response. She wipes her abused hands on her skirt and hides them in the pleats of the fabric. She’s ashamed of them, he thinks. Probably doesn’t have any glycerin to soften them or ease out the redness. “A dust devil. A soldier. What are you?”

“The name’s Geoffrey Scott, Ma’am.” He tips his hat. “I use both names.”

“Sophia Hughes,” she answers. “Madonna of the Muddy.” She laughs, seeming suddenly conscious of her English accent and maybe aware that her response could seem strange.

She has an odd sense of humor, Geoffrey Scott decides. But she’s fetching. That’s for sure. “Where you from?” he says, shifting his weight from one foot to the other. “You talk different. Say something else.”

The blood rises in her face, lifts to the high point of her cheek bone. He wonders if she’s ever seen a stranger, especially as dusty a one as he is, even though the settlers of this place must have seen a little dust in their time. But he can tell she’d like to check herself out in a looking glass, the way she’s adjusting her hair. Almost primping. He hasn’t seen a woman primp in some time.

“You look like the desert floor itself, sir,” she says, patting both sides of her bun. “You’re probably starved.”

“You know something I don’t?” He laughs a wheezy laugh, his lungs coated with more silt than he can measure.

“I baked three days ago. There’s a bit left. Of bread.”

But then Adababa appears over the small desert rise behind the woman’s house which is built out of sticks and stones and slathered mud. To her, the camel must look like a misshapen horse with a malignant tumor on its back and a head too high for good confirmation. Her eyes widen. She sniffs. “Oooh–fh,” she says, twisting her face.

“I know what you mean,” Geoffrey Scott says, moving toward Adababa to reassure him with an outstretched hand. “This here’s Adab Abib. Better known as Adababa. My business partner who could stand a good currying. I was counting on him staying behind that hill.”

Adababa peers down its nose at Sophia who stands in her barren yard in mended clothes and hands buried in their folds. A haughty look, actually, dwarfing Sophia and the slanting, sliding, oozing hills of dried mud all around, baked stiff into place. She reminds Geoffrey Scott of an actress playing her part on a stage filled with nothing but these hills split down the middle, their parched cracks leeched of any moisture. A strange and powerful beast has appeared out of one of these cracks, the likes of which she has never seen before. And it has the exceptional gall to look down on her with arrogance.

“A descendant of Ali Baba?” Her lips twitch. Is she smiling or is she nervous, Geoffrey Scott wonders, remembering the señorita in Santa Fe, the one he would have chosen if they hadn’t had to leave so fast.

“Absolutely not. No thief, this one,” he says, slapping the camel on its hindquarter and sending it to the closest creosote bush. “Eat those leaves,” he says, then turns back to Sophia again. “Adababa’s gotten me through some rough spots.”

“An odd way to speak of an animal, I would say. But Ali Baba is not a thief as you imply. That term is a password. That’s how the story goes anyway.”

He shrugs his shoulders, not caring much one way or another.

Sophia keeps her distance from the woolly animal and its smell. “That camel has long eyebrows and eyelashes.”

“The best part is that Adababa can eat anything, I tell you. Cactus and thistles. Thinks the desert’s his personal banquet.”

“How did you come to be traveling with a camel in Utah Territory?”

“Begging your pardon, Ma’am, but this isn’t Utah Territory.”

Because Adababa keeps wandering close to their conversation, Geoffrey Scott puts up his wait-a-minute hand to Sophia, ties the camel’s front feet together, and tells it to sit. “Only Brigham Young’s grand vision for himself and his followers,” he continues. “This here’s Arizona Territory. Might even be Nevada before you know it.”

Geoffrey Scott’s been told, just last week, that the Arizona Territorial Legislature sent two delegates with an invitation to send a representative from St. Thomas to the next session. But, besides that, he’s heard talk that Nevada, the new state, is anxious to claim the town for itself. Needs cash and population, though there isn’t much of either he can see. Sophia best catch up on the news. He knows what he’s talking about.

“I have read about the three wise men in the Bible. Their camels,” she says, a hint of mischief in her eyes as she skirts the topic of St. Thomas belonging anywhere except in Utah Territory. “But they belong to another part of the world entirely. Africa. Persia.”

“Think again,” the man says, the camel now settled onto the ground, content to chew on the branch that droops close to its nose. “This here’s a Dromedary, a one-humped camel. Bona fide property of the U.S. Military. Seventy-five in all shipped from the Araby. Old Jeff Davis worked Congress over to get these animals sent to Texas on a steamer.”

“Jeff Davis? Wasn’t he a Confederate?”

“Not only that, M’am. He left Congress. Resigned everything to lead the Confederacy. Sorry man, in my opinion. Except I’ve grown fond of camels, truth of it. But no one knows what to do with them now. Horsemen don’t like them one bit.” He pauses for a beat, but not a long one. “Don’t know what to do with the freed slaves either. Even the freed slaves don’t know what to do with themselves.”

“Camels brought here for the military?” she says, again side-stepping the subject at hand. You jest.”

“No joking here.”

Sophia laughs as if laughter could cure the confusion she must be feeling this morning, but, to Geoffrey Scott, something seems out of whack. Maybe he’s lonely for somebody who reminds him of his mother. Or, maybe, the demanding sun is sucking her brains dry. It sucks everything dry—even the plants the woman’s trying to grow. He notices how straggly and starved the seedlings look in the brick-like clay soil. The sun is amorphous, the way it leaks heat and bleeds light beyond its circumference. The autumn sky seems a mere stage for glaring yellow sunlight taking up too much room.

“This desert is so unlike my birthplace in England,” she continues, wringing her hands. “Skies are always leaden there. Clouds block the sun. Rain. Mist. Drizzle. A blissful haven from a mad, brazen sky like this one.”

He decides he’ll let her talk. She needs an ear to listen. He removes the pack from his shoulders and parts his lips in a lopsided smile. He’s seen better days but knows he’s still young and vital. He tips his Union-style cap which doesn’t match the non-military clothes. His pale green eyes assess her, and, even though he’d rather not, he’s more attracted to her than he’d like.

“Your eyes are green,” she says. “My husband, Charles, has brown eyes, and Mr. Milhaus . . . had brown eyes, too.” She pauses as if in a trance, her head slightly swaying. “But he stranded me in Salt Lake City, he did. Left me by myself—a hatmaker in the midst of a passel of practical women. Some thought me self-satisfied and disinterested in furthering the Kingdom of God. All because I love to make hats.”

“Where’s your husband right about now?” he asks.

“He’s helping dig a canal,” Sophia says. “Water, you know. He’s usually off on one of his mail runs. You’ve heard about the mail and how it’s supposed to be delivered, rain or shine.”

She looks off into the distance, a hint of loneliness in her eyes, and Geoffrey Scott tries to fathom what it must be like to live so much of the time alone in the middle of nowhere. But he’s starving. First things first.

“Excuse me, Ma’am,” he interrupts her reverie, shifting his weight from one foot to the other. “You mentioned bread?”

“Oh, of course. Forgive me. Your arrival unhinged my mind, and the shock of a camel in my yard! Please forgive me.” Her hands flutter through the air like two delicate wings. “You must be ravenous.”

“You’re pretty,” he says, looking at Sophia too directly, his expression almost wolfish. He’s been without a woman for a good, long time, since the early days of Ft. Mojave at least, and the few women supplying the fort were usually passing through, never to be seen again.

She turns away, as if to hide her response. Maybe she hasn’t heard those words for a while. Maybe she wants him to say them again. She pulls a wet hand towel out of her clothes basket and folds it over the line of rope secured between two mesquite bushes.

“Excuse me, sir,” she says, collecting herself. “I have to hang the last of this wash before it stiffens into boards. Then I’ll secure some bread for you. But remember, real bakeries do not use mesquite bean flour like I do.”

“I have time,” he says, resting one leg on the highest sandstone step and checking through the contents of his pack. “One thing I have plenty of, though I am hungry. I see my camel has found a few bites.” Adababa has reclined in the shade of a greasewood bush and chews its branches, seeming content.

“This task will be brief,” she says. “I promise.” She reaches into the cloth bag she uses for clothespins and draws out chunky, notched pieces of mesquite about four inches long. “Look at what my husband made for me. He’s carved these heads. See? A woman with long hair like my own, and a man with a beard wearing a bowler hat. I felted one for him just like that one. Sometimes they have conversations. But you must think I am dazed in the head when I tell you things like that. I get hungry for good conversation. I do.”

When will her husband be back, Geoffrey Scott wonders. Hopefully he’ll appear soon out here in this conglomeration of mud huts and lean-tos, though who am I to judge conversations between two clothespins? He closes his hand around his mouth to hide his grin.

She pulls out pieces of the wash and then tucks a two-legged something that looks like long underwear back into the pile quickly, as if to hide it. She rolls the remaining wash in a kitchen towel and puts it back in the basket which she leaves on the ground. “Forgive me,” she says. “I should not keep you waiting. I have quite forgotten my manners.”

“I’m obliged, Ma’am.” The dusty, wrinkled, road-weary Geoffrey Scott is nimble, and there’s no sound of creaking knees when he stoops to a sit. She disappears behind the burlap curtain hung across the door.

Seated on the step, Geoffrey Scott looks at his rumpled clothes. He’s worn them for sleeping, riding, walking for many days, and there are stains across the front of his shirt. His boots are no longer stiff and strong. The toes curl. The sides are loose. He realizes he’s no prize at the moment though he’s strangely drawn to this woman.

She returns to the doorstep with a chunk of the tough, crumbling bread in hand, and a wrinkled napkin. “The best I can do, sir.”

“I’m obliged, you’ll never know how obliged.”

“I wish I had strawberry preserves,” she says, handing the food to Geoffrey Scott. “Honey. Tea. Lemon curd. Some shortbread. High tea. Where have you come from? You have been traveling for days, it would seem.” Folding her arms tight against her chest, almost as if she is hiding her feminity, she stands and looks down at him while he gulps the bread.

“Originally hail from Kansas, Ma’am.” He eats the bread with two hands, almost as if he’s playing a harmonica. Sophia smiles though she keeps her lips pressed together. “More recently, I had to get away from Fort Mojave, about a hundred miles south of here. Back home in Kansas, the Border Ruffians attacked anybody resembling an abolitionist before the War, especially when they were roaring drunk, which was most all the time. I left in ’58. Helped build a road from Fort Defiance clear through to the Colorado River. Two years we worked, readying it for travel. That’s how I ended up south of here.” His face darkens to black space. He pauses for a long time. “Important to guard the Indians from their own land, you know,” he says, then laughs from deep in his throat. “Of course, the white man will take better care of the property than the primitives. That’s the better part of wisdom these days.”

Sophia listens attentively to his sarcasm. “I always thought those people were too basic for their own good. More advanced techniques might be good.”

He doesn’t respond to her comments and points to Adababa mashing mesquite with its teeth and long tongue. “This here’s my mount. Everyone in this idle-not-and-work-hard-all-and-every-day community will be curious to see him. In fact, I’m surprised they haven’t shown up already.”

But a few bodies are peeking out of canvas and screen doors even if they haven’t revealed their faces. Geoffrey Scott has seen the movement behind doorways and wonders when one or two inhabitants of St. Thomas will be brave enough to come to the sideshow. There’s not much here in this place to brag on. Or probably even talk about. These people seem to be beginners at living, squirreling away from the sun. But he’s mesmerized by Sophia tenting her hands beneath her chin and smiling at the sight of this animal in her backyard, a folded blanket across his back, a rough-looking saddle with a horn at the front, and the black, haughty eyes. Its split lip is manipulating the thorny branches as if they were supple fingers, unbothered by the sharpness of thorns against the roof of its mouth.

She cautiously takes a few steps toward Adababa and holds out her hand for the animal to sniff, though she backs away when he does. Adababa is gigantic compared to her. This time the camel looks up at her, calmly, still. Even seated, it seems to be the king of some exotic desert palace with no appreciation for commoners.

“Adababa?” she says its name, then turns back toward Geoffrey Scott. “From Fort Mojave? I have never heard of such a place or heard Charles mention it. I thought we were the only ones touched enough in the head to try and survive in this inhospitable desert.”

“Military post,” he answers. “About a hundred miles south of here where the Colorado’s more predictable. Aha kwahwat. That’s what the Mojaves call the river. And, believe this story, Adababa swam across once to get to California, then later rode me past a slew of Indians so I could get supplies to Lieutenant Beale. With rubber rafts, you know. Natives still live on both sides down there, even though the military’s been rounding them up. One of them is trailing me now. Kwanyumai. Means ‘warrior.’ I call him Kwami. Thinks Adababa’s his as much as mine, though he makes noise about nothing belonging to nobody.”

Sophia claps her hands against her cheeks, as if all of this is too much to take in. “I should not ask, but are you on the wrong side of the law? A deserter maybe? Forgive me for asking, but you’re like a genie from a bottle.”

“You have a big imagination, but maybe I could bother you for water?” he says, still chewing on the tough bread.

“I’ll see what we have.”

She picks up the basket and balances it on her hip. “I’ve got to get this laundry inside before it turns to a wadded crumple.” With one of the hands she’s kept hidden from him, she pushes aside the canvas flap, enters, and Geoffrey Scott can hear her moving dishes in the kitchen. Then she’s on the porch again, carrying half a cup of water in a cracked cup. Geoffrey Scott watches it slosh as she balances on the uneven steps, though not enough to spill over the sides. He wonders who this woman is. What she’s all about. Not someone he expected to find here. So vulnerable. Fragile even.

AUGUST 1867

Geoffrey Scott does a double take. Is that what he thinks it is?

He’s left Fort Mojave behind—buildings, stockade, new fence—and wandered into the desert to the tune of a few cicadas repeating their crrr-ing call. The night is lit by a fingernail moon and more stars than he’s ever seen before. Millions. Billions. But there’s an outline against the night sky. A bizarre repeat of something he’s seen before. Head raised high. The hump of a back and the arch of a neck accentuated by moonlight. That silhouette looks like Attah Allah standing in an outcropping of rocks but looking more like the carving of an animal king looking down from a high place. Tonight it’s not foraging. Perfectly still against the backdrop of a starry sky in its kingdom of sand and bush.

It takes a few steps. Geoffrey Scott takes his chances.

“Adababa,” he yells into an almost empty desert.

No sound. No answer.

But now he’s sure. That silhouette is the camel he rode next to on the first expedition from Texas. The one he’d ridden to the Colorado River to get supplies to Beale. Untethered, unhobbled, and uncoralled. The Civil War’s over and Jefferson Davis, the main honcho for bringing the camels stateside, well, he’s gone. What a joke. But what’s Adababa doing here? Tonight?

Geoffrey Scott feels a sharp wind cooling his backside. He lifts his shoulders as high as they’ll go, rotates them backward and forward to ease the stiffness, then reaches for the thin roll of blanket tucked into his pack. What does this all mean, he wonders, then shakes himself from the allure of pies in the sky. He’d better get the animal back to the fort where it belongs.

Tossing the blanket over his shoulders, he stumbles through the scattered rocks and approaches the camel. He shakes his head. Frustrated. When he looks closely, he sees that no one has tended to the animal’s well-being.

“Hi there, Baba. What you doing out here, no hobbles on your feet? You run away?” Adababa nuzzles into his shoulder and groans, a familiar sound Geoffrey Scott’s heard before.

The army’s been careful with their valued cargo from the Levant, even brought their own handler with them over the high seas—Hadji Ali, the man who’d taught Geoffrey Scott how to get a camel to do what a man wanted, something most of the military never bothered learning. Few soldiers are interested in the camels or their handler—a man who speaks foreign gibberish, they say. A believer in Mohammet.

Geoffrey Scott’s glad he never signed up for the uniform. Never wanted to. The idea never settled well with his Congregational/Abolitionist sensibilities anyway. Thank the Lord Above he knew how to build things. Keep himself employed and away from the enlistment office, but uniform or no, he’s helped carve the Great Wagon Road out of his bone and blood. Under Lieutenant Beale. A military road even if most of the builders were just plain working men. An accomplishment not small in anyone’s memory. Then he’s hung around Fort Mojave to help build its walls and repair its leaks. But now, as of last week, the government’s claimed the Mojave’s land. Told the tribe who knows best. He’s had enough.

He takes a long look at Adababa—alone in the desert, free as a wild animal and yet not wild. No one’s tending him. No hobbles. No broken rope around his neck. Property of the U.S. Government even if soldiers’ve been pushing some of the camels over cliffs. Favor their horses. Put off by exotic animals. But he knows this particular one. He’s ridden on its back: ten feet tall when his head’s straight in the air, about nine feet long and five feet wide, probably a ton. A camel can outlast and outpack any horse or mule in the Mojave Desert. Adababa’s his camel as much as anyone’s.

Geoffrey Scott scratches his nose with the back of his hand. Impulsively, he decides. He and Adababa will head north. Together. On the Old Spanish Trail which the Mormons have turned into the Salt Lake Road. Look for that salt mine Kwami’s told him about. Find pieces as big as a man’s fist. Pure, clear, more valuable than diamonds. People will pay for salt. That’s what this night is all about. This camel. This vision. God’s gift indeed.

* * * * *

The crescent moon. One side of a parentheses, he laughs to himself. A future open to him. Geoffrey Scott from Osawatomie, Kansas, reaches over his shoulder and pats himself on the back. He has a partner now. A camel. He’s about to become something more important than he’s been. He smiles, the full moon itself. Too bad his mother isn’t alive to see this. Then he shuts his eyes to escape the memory of blood haloing her head, pooling on the slats of the porch in Kansas, her stillness.

Wherever the souls of his parents are, he’ll make them proud, though he’d best not forget his father scoffing at pride. That man never had hopes—high or low—pushing his only son out the door when his mother was killed. How he, Geoffrey Scott, came to be, he’ll never figure because that coupling was unimaginable. He never saw tenderness of any kind. Or nakedness. Those parents had moved to Kansas from Massachusetts to cultivate fertile land, to live wide-open, and to help protect the territory from the spread of slavery. But then, something called Bleeding Kansas happened. Porous borders with Missouri. Slavers who hated anti-slavers. Slavers with their shotguns and their moonshine. His mother said no good-bye at all. She’d been so kind to everybody, no matter who. Even to his cantankerous father—the man he both loved and feared. He could still hear the man’s crazy talk in his head.

He ties Adababa to a bush with a long rope from his pack, uncoils the horse whip he’s carried from Kansas, and forms it into a circle on the sand. He takes his blanket off his shoulders and lays it inside. Snakes won’t cross that line.

While Geoffrey Scott sleeps, dreaming about salt mines and the people who’ll pay top dollar, Adababa eats the first, the second, then all the branches on the bush to which he’s tied, mashing the brambles and thorns in its teeth. Then the camel wanders into the desert, snaking the line tied to his neck, forming a myriad of sand patterns, unmindful of his business partner sleeping inside the circle of rope. He grazes from bush to bush, from yucca spike to creosote leaves, and then stands still as a statue on another hill—this time for the eyes of Kwanyumai, the Mojave, who never sleeps by the fort at night even though he walks and hammers on its rising walls by day. Geoffrey Scott came across him about three years ago. On the other side of the river. Gave him yellow medicine for his chills and shivering.

But tonight, the stars are legion. The sky is alive. Kwami is alone, unseen by Geoffrey Scott. The camel strolls into the night with no invitation or no capture—Attah Allah, as the Arab has taught Geoffrey Scott and as he has taught Kwami. God’s gift. The Indian, if he spoke of such things, would use other words and say the camel is a gift from Mutavilya. Alone on the hilltop, the animal must have come for Mutavilya’s reasons. Kwami moves quietly through the night, his moccasins soft in the sand, then catches hold of the rope hanging loose from Adababa’s halter. He reaches up and rubs the side of the camel’s nose with two fingers. Good animal. Strong. Taller than Kwami. Almost two Kwamis for one Adababa. Together, they walk toward a shallow cave where the Mojave hobbles the camel by his side. This camel belongs to him now. It is a gift. He rolls into his own blanket and closes his eyes for the night, all of this while Geoffrey Scott tosses in his own bedroll, dreaming of Adababa close by.

* * * * *

Rising before the sun, Geoffrey Scott witnesses the emptiness. He panics and coils his rope and whip, tucks them into his saddlebag, and follows the trail left by the camel and the rope. At first, he only sees the unusual footprints and snaky imprint of the dragging rope, but then there are human tracks to the side. Over rocks and mesquite, Geoffrey Scott follows these prints to the cave of red sandstone, which is more indentation than cave—a windbreak. On a bed of sand cradled next to a rising wall of striated sandstone, he sees Kwami wrapped in a blanket, his long black hair freed from its usual band of deer leather and fanned out across his cheek. Adababa dozes beside him, his legs stretched in front and a rope tied around his back hooves.

The light of dawn works its fingers through the myriad of rock formations, the deep shadows paling to an indistinct gray. Geoffrey Scott finds a long branch to tease the black hair away from Kwami’s cheek.

“Wake up, you lazy Injun.”

Kwami wakes. He’s startled to see Geoffrey Scott standing there, so far away from Fort Mojave where they usually meet.

“What are you doing with my camel?” Geoffrey Scott asks.

“He comes to me,” Kwami says. “Last night.”

“You got it wrong. He came to me.”

“No. To me. His shadow against the moon.”

There is no arguing with Kwanyumai’s certainty, but Geoffrey Scott believes the Indian doesn’t understand the order of things. “You don’t believe in ownership anyways. I had him first.” Chin talk.

“I did.” Raised-fist talk.

Adababa remains seated, unable to rise with the hobbles on his back legs. His luxurious eyebrows magnify the handsomeness of his face, long, thick eyelashes brushing the air, opening and closing. Looking wise, impartial, and imperial.

“I could shoot you.” Geoffrey Scott puts his hand on his gun which has never been aimed at a human being or animal even. “But then,” he tempers his initial impulse and folds his arms. His bravado turns to gest. He laughs. “I guess you could pierce my side with an arrow.” He points to Kwami’s quiver and the arrows bundled inside. “Where’s this argument leading anyway?”

Something diffuses between them. The anger dies a simple death. Maybe because the two men are friends. They’ve been learning each other’s language back at the fort.

“We’ll be business partners,” Geoffrey Scott says. “How about that?” He offers his hand, though he isn’t sure Kwami understands business the same way he does. He isn’t sure if his deal with Kwami can be decided with a handshake.

And Kwami, on his part, keeps close watch on Geoffrey Scott and Adababa, as if he’s making sure neither of them goes too far away. Mr. Scott is not a man of Kwami’s tribe, after all. He has light eyes and strange skin. And the camel has been given to him by Mutavilya.

SEPTEMBER

“You better make yourself scarce,” Geoffrey Scott says to Kwami, the river roaring in the background. “Your kind’s not too popular around here.”

Kwami ignores him, squatting, tossing rocks into the roiling current. Fast. Savage. Powerful. He seems spellbound by the river.

“Hey. You hear me? You better get while the getting is good.”

No response, only another rock sailing through the air and disappearing into the fast-running water.

The canyon walls are pressing tighter here. The river’s grown preposterously huge arms to wrestle the channel making its way south. Broad. Brackish. Red with sands picked up along the way, turning over and over, red sand rolling.

Geoffrey Scott knots the rope attached to Adababa’s halter and takes a long look at the ferry that crosses the river. Hardy’s Landing—a hefty line of woven hemp stretched across and a flat-bottomed boat waiting on the other bank. But then, suddenly, Adababa spits, startling both Geoffrey Scott and Kwami. Then the camel turns and twists as if it’s swallowed a jumping bean.

“Whoa,” Kwami shouts and jumps to full height. Then, he pulls his shoulders down and rolls his head around to straighten it. “Baba,” he says in a low voice. “You don’t spit.”

Geoffrey Scott tries to stroke the camel’s neck, hoping to calm the nervous animal, but Adababa’s acting like the water is an enemy, maybe remembering the way it swept the horses downstream the time they all crossed. It skitters sideways, then spits again and swings its neck, threatening Geoffrey Scott because it could crush him against a rock and squeeze the life out in not much time. Adababa’s one perturbed, unpredictable camel that could crush him against a rock and squeeze the life out in not much time.

Kwami quietly works his way to the camel’s side and reaches out to squeeze its thigh gently. Then, best as he can, he strokes the camel’s neck. It’s riled up big time, showing another side of itself the two men have never seen before.

“Settle down, Baba,” says Geoffrey Scott, jumping back to keep his distance from the kicking hooves. “We’re not crossing this beast today. When’d you start spitting and kicking anyway?”

Adababa turns its back on the water and on Geoffrey Scott, pulling on the rope and prancing angrily on its dinner-plate hooves.

“Temperamental thing, aren’t you now?” Geoffrey Scott says. Adababa keeps overworking his tether. Deaf to any reason except his own.

“It won’t do you any good to be ornery.” Geoffrey Scott holds tight in this seesaw battle.

Kwami steps closer, then puts both of his large hands on the animal’s side and mouths a few words, indiscernible to Geoffrey Scott. Maybe some Indian words. Some chant to remind Adababa he’s among friends. Gradually Adababa settles, not yanking the rope so hard.

“That was a tantrum,” Geoffrey Scott says to the camel who’s now chewing on the branch of a tamarisk as if nothing had happened, a committed sampler of anything with leaves. “Hey. Kwami. You ever seen Baba like this?”

Kwami shakes his head then walks back to the edge of the river and squats.

“Easy for you to say now he’s calmed,” Geoffrey Scott calls after him, envious of the nonchalance of the man.

“Adababa understands. My words. We are like brothers.”

Geoffrey Scott thinks he hears what Kwami is saying, but there’s too much background noise from the river. Maybe Kwami thinks Adababa’s more in tune with him for some reason. Foolish thinking. He looks back to the river and squints his eyes at the narrowing of the canyon. The Colorado is large. Humbling. Domineering in a land of mountains of stacked, dried mud and valleys of rock and dirt. Kwami seems to be listening to the subterranean roar of water over rocks—the unseeable forces submerged. “Aha Kwahwat,” the Indian says out loud, as if the water’s a fire that needs close watching.

“Colorado. The Red River,” Geoffrey Scott says, smiling, tilting his head back, and proud of the fact he’s speaking both Spanish and English. Kwami, however, seems more interested in the water. But no matter how big the Indian is, Geoffrey Scott thinks, he’s still diminutive next to that big-ass camel that could hurt a body if it had a mind to. Wouldn’t want to be on the wrong side of the fence when that animal’s ire is up and running. But then he wonders again about Kwami who seems to understand the animal better than Geoffrey Scott does even though he doesn’t believe that for one minute.

When they’d first met, the Indian had been shaking like a leaf. Pitiful with ague. After the medicine and more than one painful grimace, the Indian wrapped himself in the blanket Geoffrey Scott had given him and sat by the fire into the night. A year later, Kwami appeared again, the same man, but this time a painted warrior dressed in loincloth and war bonnet, pointing an arrow at Adababa’s heart while it carried Geoffrey Scott to get supplies to Lieutenant Beale stranded on the other side of the river. Both of them could have died then. No more pulse. Heartbeat. Nothing. Painted men running in every direction, the situation a mad scramble. And now, he’s squatting next to the river, quietly contemplating its fury, maybe even its blessings before the three head north. How his father would have loved the irony: the son of an abolitionist, a camel, and a Mojave Indian.

“Time for you to skedaddle,” he says. He looks carefully up and down the banks, wary someone might be watching him talking to a red man which was trouble to most minds. “Get yourself out of here. Now.” He hands the rope to Kwami.

Kwami starts climbing with Adababa, but then turns his head back and points to the cliffs. “Mojaves know secret places in rocks.”

Somewhere, in the myriad of chats he’s had, Geoffrey Scott’s heard of a rocky labyrinth near the river carved out by the Indians. How the natives scramble over tortured rocks, tunnel through, negotiate this cobweb to travel from south to north. Hiding from those tribes that would pursue them or seeking shade in this hostile land. But this is the first time he’s heard mention from Kwami. “You know about those?”

“Some.”

“Would Adababa fit?”

“Some.”

Kwami starts to climb again, Adababa behind him. He never smiles, and in this way reminds Geoffrey Scott of the very wooden Indian someone had carved and placed at the temporary entrance to the fort—a cockeyed notion of a red man. Kwami is silent most of the time, though Geoffrey Scott knows him for more than this. If there were such a thing as blue ribbons given out in a competition for learning English, Kwami would win. By a long shot.

“Time to be gone, you two.”

The Indian pulls Adababa carefully by the rope around its neck. “Follow your master, Baba.”

“Master?” though Kwami is beyond hearing his response. Geoffrey Scott can’t believe what he’s just heard. “You gotta be joking with that one.” Then he shouts. “I need to get more information about where we’re going. Take care with Adababa’s feet. He’s been complaining.”

Never mind what Kwami thinks, he says as he trudges off to Hardy’s Landing, sinking below the surface in the unreliable sand, some of it filling with water after he steps, but he’s glad his companions are headed where they’ll be invisible. Somebody could ask questions. The camel’s a circus, hands down. Everyone’s always curious, military or no. “What in the hell’s a camel doing in these parts?” people usually say. And everybody’s frantic about Indians these days. Without those two, Geoffrey Scott might get a good meal. His provisions are smelly from the heat even though Fort Mojave is not that many miles away. But 110+ degrees is too hot for anything. The soles of his once-strong boots are thinning. No one can walk far before they’ll fry like bacon—the sun sizzling skin and bones. The sand a griddle. And rocks. Eternal rocks.

With Adababa’s ability to survive in waterless places and Kwami’s knowledge of the land, he thinks as he negotiates the terrain toward Hardy’s Landing, they might be able to make it through the fire-and-brimstone rocks and cliffs and skirt the worst canyons. Maybe they should take the rough military road he’s heard about. The one carved out by surveyors, boatmen, geologists, engineers—curious types figuring how to get from the Gulf of Mexico upstream. Adababa would do best without rocks, that’s a given. The Old Santa Fe will most likely be best, though he’ll ask at the settlement just ahead, complete with a store, billiard room, dining saloon, a blacksmith, a warehouse, and several houses, or so he’s been told.

After scrambling over a small cliff face, Geoffrey Scott sees a lone man washing clothes. He pulls on his groin, absentmindedly remembering the grains of sand turning his private parts red. Sandpaper in his britches. He pauses and sips the too-hot water in his canteen, careful to ease the scalding liquid over his tongue. It’s September. Indian Summer. Way too hot. The man doing the washing wears no undershirt, his bare feet cooling in the harmless eddy. Geoffrey Scott also sees a soldier on the porch of the main building, this one fanning himself with a military cap, leaning against the adobe wall in a cane chair. No use for discipline in heat that keeps a body from going anywhere or doing anything.

Hacksaw military, Geoffrey Scott thinks to himself. Drifters with nothing else to do. Bludgeons with dull knives trying to be a part of something that’s not anything yet. The whole endeavor trying to get organized though nowhere resembling organization yet. But damn, that Kwam’d be a tough one to round up, so soldiers, don’t get ideas.

The last stretch of sand, damp and deep, requires heavy walking. And heavy thinking. Adababa might be the property of the U.S. military, Geoffrey Scott tells himself, but who cares whether or not the camel’s stolen or discarded property? It’s traveling with us now. And nobody’s going to change that. Me, Kwanyumai, and Adababa are on our own. Not an expedition, military or otherwise. Just a crazy troupe of travelers.

He feels like he’s getting nowhere as his feet sink in the endless sand but nevertheless keeps an eye on the half-dressed soldier nodding off on the front porch. Everything’s slow. Heat like thick molasses. Hot wax. No shade. No escape. Fort Mojave wasn’t like this. Many more soldiers. Lots more activity to protect the military and the emigrants. But it’s no small irony the fort’s been given that name. Replacing the Mojaves like it is. Geoffrey Scott shakes his head and wonders how anyone can tell someone else what they can’t do. Where they can live. What they can eat.

He battles the last few sandy steps and finally reaches the porch of Hardy’s headquarters.

“Howdy,” he says to the soldier who’s half dozing. “Mr. Hardy anywhere around here?”

“Inside.” The man says, then closes his eyes again, not inclined toward conversation of any kind.

Geoffrey Scott climbs the stairs of the main building of Spanish adobe. He opens the door, then hears his footsteps echoing on the red tile floor, the sound larger than the room. Cooler interior, thank God. A relief. More footsteps. A hallway.

Hardy is huddled over a desk in a back office—a man parched and dry from the desert like everyone else who comes here. His face is tanned the color of a kidney bean, almost a dark red, and he wears a battered straw hat that seems more a habit than something to shade him from the unmerciful sun. It’s set back on his head at a tilted angle.

Geoffrey Scott knocks on the half-open door. “Excuse me sir,” he says, pushing the door enough to be seen. “I’m on my way north. Thought you might have some suggestions.”

“I might know a few things,” Mr. Hardy says, half-attentive, thumbing through the papers on his desk. He finally looks up to see who’s talking. “The best advice is to keep goin’. Take the Old Spanish Trail. You can follow the river best you can, but that would be a trial you wouldn’t want.” With his finger that’s been separating paper, Mr. Hardy tips his hat even further away from his face and makes more of an effort. “Bring yourself inside. Couple of settlements north of here. Semi-farmable land, if you’re not afraid of the Mormons. St. Thomas. St. Joe. Mormon towns. Even Callville at the fork of the Muddy and Virgin. Tryin’ to compete with me, think of that, but they’ll never succeed with the river like it is.”

He straightens the few papers into a neat pile. “Keep goin’, young man. Those Mormons are clannish and maybe you won’t get past that. But you might. If that don’t work, there’s a road goes through Las Vegas Meadows into California. Or you can head East to Colorado Territory. Wide open about now. Everybody and California and gold, though the Indians are testier than ever. Watch out for them. Military’s rounding them up where they can be watched. Watch out for them. Trouble. That’s what they are. Think this is their country. We’ll grab them and turn ‘em over to the military if they come here.”

Geoffrey Scott says nothing in response.

“Always hungry. Thieving. Stealing.”

Geoffrey Scott still knows more than he’s hearing and isn’t about to divulge the hiding place of his traveling companions.

“Why don’t you have a bite to eat before you go?”

“Suits me,” he finally answers.

“Got a cook’ll rustle something up for you. Excuse me from joining you. Work to do.”

Questions. Answers. Supplies bought. A hot meal. Over an hour before Geoffrey Scott is climbing the same slope as the camel and Indian had done before him. Looking for his compatriots and hoping Hardy or the soldiers don’t catch sight of Kwanyumai or Adababa passing Hardy’s Landing at the tops of the cliffs, making their way north.

* * * * *

OCTOBER

Geoffrey Scott stands with a pack on his shoulder in what passes as a backyard with its crooked fence of mesquite and leggy creosote. Unknown to him—this man in a dusty cap with an emblem of crossed rifles fastened at the front, this wearer of a pair of nondescript pants and shirt which was crisp and new once upon a time—is interrupting someone’s weekly ritual.

The locusts sing their predictable song, no cloud hovers anywhere in the too-blue sky, and everything loses color in the heat. The heat, its oppression and everywhereness, is strong. He wipes his brow with his much-used handkerchief and stares at this ragtag town. A few mud houses, makeshift tents, and the skeletons of houses to come—signs that the settlement’s working toward respectability. Then his eyes focus on the woman in the yard dressed in a long skirt and soiled blouse. He watches her biting down on the clothespin between her teeth. She wipes the hair from her face and the perspiration from her cheeks.

“Must have been wandering too long,” Geoffrey Scott calls out, touching the brim of his sun-bleached, barely blue hat as he comes closer. “You some kind of vision?”

“YOU are the apparition,” she says, startled, a slightly nervous laugh at the edge of her response. She wipes her abused hands on her skirt and hides them in the pleats of the fabric. She’s ashamed of them, he thinks. Probably doesn’t have any glycerin to soften them or ease out the redness. “A dust devil. A soldier. What are you?”

“The name’s Geoffrey Scott, Ma’am.” He tips his hat. “I use both names.”

“Sophia Hughes,” she answers. “Madonna of the Muddy.” She laughs, seeming suddenly conscious of her English accent and maybe aware that her response could seem strange.

She has an odd sense of humor, Geoffrey Scott decides. But she’s fetching. That’s for sure. “Where you from?” he says, shifting his weight from one foot to the other. “You talk different. Say something else.”

The blood rises in her face, lifts to the high point of her cheek bone. He wonders if she’s ever seen a stranger, especially as dusty a one as he is, even though the settlers of this place must have seen a little dust in their time. But he can tell she’d like to check herself out in a looking glass, the way she’s adjusting her hair. Almost primping. He hasn’t seen a woman primp in some time.

“You look like the desert floor itself, sir,” she says, patting both sides of her bun. “You’re probably starved.”

“You know something I don’t?” He laughs a wheezy laugh, his lungs coated with more silt than he can measure.

“I baked three days ago. There’s a bit left. Of bread.”

But then Adababa appears over the small desert rise behind the woman’s house which is built out of sticks and stones and slathered mud. To her, the camel must look like a misshapen horse with a malignant tumor on its back and a head too high for good confirmation. Her eyes widen. She sniffs. “Oooh–fh,” she says, twisting her face.

“I know what you mean,” Geoffrey Scott says, moving toward Adababa to reassure him with an outstretched hand. “This here’s Adab Abib. Better known as Adababa. My business partner who could stand a good currying. I was counting on him staying behind that hill.”

Adababa peers down its nose at Sophia who stands in her barren yard in mended clothes and hands buried in their folds. A haughty look, actually, dwarfing Sophia and the slanting, sliding, oozing hills of dried mud all around, baked stiff into place. She reminds Geoffrey Scott of an actress playing her part on a stage filled with nothing but these hills split down the middle, their parched cracks leeched of any moisture. A strange and powerful beast has appeared out of one of these cracks, the likes of which she has never seen before. And it has the exceptional gall to look down on her with arrogance.

“A descendant of Ali Baba?” Her lips twitch. Is she smiling or is she nervous, Geoffrey Scott wonders, remembering the señorita in Santa Fe, the one he would have chosen if they hadn’t had to leave so fast.

“Absolutely not. No thief, this one,” he says, slapping the camel on its hindquarter and sending it to the closest creosote bush. “Eat those leaves,” he says, then turns back to Sophia again. “Adababa’s gotten me through some rough spots.”

“An odd way to speak of an animal, I would say. But Ali Baba is not a thief as you imply. That term is a password. That’s how the story goes anyway.”

He shrugs his shoulders, not caring much one way or another.

Sophia keeps her distance from the woolly animal and its smell. “That camel has long eyebrows and eyelashes.”