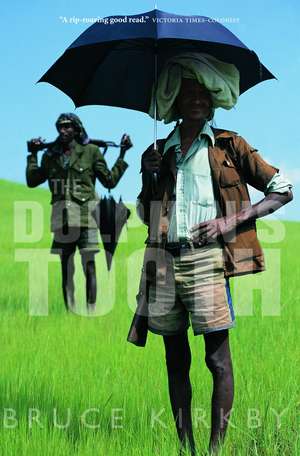

The Dolphin's Tooth: A Decade in Search of Adventure

Autor Bruce Kirkbyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2007

Preț: 112.46 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 169

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.53€ • 23.39$ • 18.09£

21.53€ • 23.39$ • 18.09£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780771095672

ISBN-10: 0771095678

Pagini: 370

Dimensiuni: 150 x 240 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.62 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

ISBN-10: 0771095678

Pagini: 370

Dimensiuni: 150 x 240 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.62 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Notă biografică

Bruce Kirkby is a wilderness guide, paddler, mountaineer, accomplished photographer, and writer. His first book, Sand Dance, spent fourteen weeks on the national bestseller lists.

Recenzii

“It’s history. It’s photography. And it’s a rip-roaring good read.”

— Victoria Times-Colonist

“A winning combination of thoughtful and thrilling, philosophical and harrowing.”

— Vancouver Sun

“A fast-paced read, filled with near-calamitous events, bruises, blisters, bribes to local officials, and occasional gunfire.”

— Quill & Quire

— Victoria Times-Colonist

“A winning combination of thoughtful and thrilling, philosophical and harrowing.”

— Vancouver Sun

“A fast-paced read, filled with near-calamitous events, bruises, blisters, bribes to local officials, and occasional gunfire.”

— Quill & Quire

Extras

Shawn bursts through the front door of our house in downtown Ottawa, an enormous cardboard box in his arms.

“Check this out!” he yells, dropping to his knees and tearing open the lid.

I join Kolin and Jeff, two friends visiting from university, as they press close and peer in. Swirls of white elastic band fill the box to the rim, like a jumbled pot of overcooked spaghetti. Jeff kneels and runs his hands through the thin strands, stirring up clouds of chalk dust.

“Holy crap, that’s a lot of elastic.”

“Twelve kilometres in total,” Shawn smiles. “The exact stuff that is sewn into the waistbands of women’s underwear. Gentlemen, this is going to make us rich.”

A month earlier my three engineering buddies had been on New Zealand’s South Island, where they witnessed the exploding popularity of bungee jumping. Upon returning home and realizing there was nothing similar in Canada, they decided to start their own company.

“You’ve seen it yourself, Kirkby.” Shawn gets excited whenever he talks about the project. “In Queenstown tourists are lining up for hours and paying one hundred dollars each, just for the chance to jump off an abandoned bridge with nothing but elastic cord attached to their ankles. There can’t be many overhead costs. I think we’ve stumbled on a gold mine.”

The few bungee companies already in existence around the world carefully guard their secrets. Bungee cords are simply not for sale, anywhere. There are no “how-to” manuals or training courses. In fact there is no public information at all, so experimentation is going to be required.

Shawn grabs the box and disappears into the basement, Kolin and Jeff in tow. For hours they work, weaving strands of thin elastic back and forth between two carabiners. Eventually they create a cord as thick as a baseball bat, fifteen hundred individual strands in total. Before dinner they allow me a sneak preview. The white worm they have constructed does not instill confidence. It looks like a floppy, springy, fraying firehose. I feel no inclination to jump off a bridge with it tied to my ankles.

That weekend, as dawn breaks over Eastern Ontario, a group of friends secretly gather at an abandoned railroad trestle. Kolin loads a backpack with weightlifting plates; thirty-six kilograms (80 pounds) in total. He throws in a few rocks for good measure. It’s not even close to body weight, but he decides it will do. One end of the rubbery cord is lashed to the bridge railing, while the other is clipped to the heavy pack, which is then heaved up onto the railing with a clunk.

“Three . . . two . . . one . . .” Everyone tenses. “. . . Go.”

The pack topples over the edge and for a few heart-stopping seconds it plummets. Then bit by bit the cord begins to stretch, and the pack slows. Eventually it stops, well before hitting the water, and then . . . boing! . . . it bounces back up, almost reaching the railing again. Boing, boing, boing. Finally the bouncing and swinging stops and the pack is lowered to Shawn’s younger brother, who waits on the shore below. The cord is set up again. It is time for a human test pilot.

“Check this out!” he yells, dropping to his knees and tearing open the lid.

I join Kolin and Jeff, two friends visiting from university, as they press close and peer in. Swirls of white elastic band fill the box to the rim, like a jumbled pot of overcooked spaghetti. Jeff kneels and runs his hands through the thin strands, stirring up clouds of chalk dust.

“Holy crap, that’s a lot of elastic.”

“Twelve kilometres in total,” Shawn smiles. “The exact stuff that is sewn into the waistbands of women’s underwear. Gentlemen, this is going to make us rich.”

A month earlier my three engineering buddies had been on New Zealand’s South Island, where they witnessed the exploding popularity of bungee jumping. Upon returning home and realizing there was nothing similar in Canada, they decided to start their own company.

“You’ve seen it yourself, Kirkby.” Shawn gets excited whenever he talks about the project. “In Queenstown tourists are lining up for hours and paying one hundred dollars each, just for the chance to jump off an abandoned bridge with nothing but elastic cord attached to their ankles. There can’t be many overhead costs. I think we’ve stumbled on a gold mine.”

The few bungee companies already in existence around the world carefully guard their secrets. Bungee cords are simply not for sale, anywhere. There are no “how-to” manuals or training courses. In fact there is no public information at all, so experimentation is going to be required.

Shawn grabs the box and disappears into the basement, Kolin and Jeff in tow. For hours they work, weaving strands of thin elastic back and forth between two carabiners. Eventually they create a cord as thick as a baseball bat, fifteen hundred individual strands in total. Before dinner they allow me a sneak preview. The white worm they have constructed does not instill confidence. It looks like a floppy, springy, fraying firehose. I feel no inclination to jump off a bridge with it tied to my ankles.

That weekend, as dawn breaks over Eastern Ontario, a group of friends secretly gather at an abandoned railroad trestle. Kolin loads a backpack with weightlifting plates; thirty-six kilograms (80 pounds) in total. He throws in a few rocks for good measure. It’s not even close to body weight, but he decides it will do. One end of the rubbery cord is lashed to the bridge railing, while the other is clipped to the heavy pack, which is then heaved up onto the railing with a clunk.

“Three . . . two . . . one . . .” Everyone tenses. “. . . Go.”

The pack topples over the edge and for a few heart-stopping seconds it plummets. Then bit by bit the cord begins to stretch, and the pack slows. Eventually it stops, well before hitting the water, and then . . . boing! . . . it bounces back up, almost reaching the railing again. Boing, boing, boing. Finally the bouncing and swinging stops and the pack is lowered to Shawn’s younger brother, who waits on the shore below. The cord is set up again. It is time for a human test pilot.