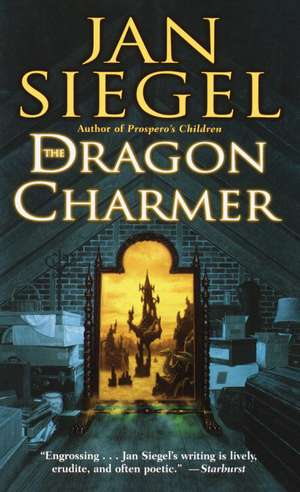

The Dragon Charmer

Autor Jan Siegelen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2002

After surviving an amazing, terrifying summer twelve years ago, Fern makes a fateful decision: to deny the mystical powers that pulse through her family's past. Yearning for a simple, quiet life, she decides to marry a man twenty years her senior, a man who insists they wed at the Capels' summer house in Yarrowdale, a place swelling with mood, marvel, and magic. For when Fern returns there with her best friend, Gaynor, ancient, sinister forces reawaken.

Yet Fern has had enough: Enough of running from her fate, enough of hiding from her Gift. As she turns to face her destiny, the real world falls away, and Fern is once again swept into another land, removed from Time, void of comfort. It will take all her skill and daring to fight her way back to the present and save the people she loves from the ever-growing danger that threatens to destroy them. And to her utmost surprise, the key to survival is a dragon with the capacity to rule the world . . . but who will relinquish it all to one man.

Jan Siegel has created an intense, fascinating world. To surrender yourself under her captivating spell is to remember how remarkably powerful a literary voyage can be.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 40.97 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 61

Preț estimativ în valută:

7.84€ • 8.19$ • 6.49£

7.84€ • 8.19$ • 6.49£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345442581

ISBN-10: 034544258X

Pagini: 333

Dimensiuni: 97 x 186 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.17 kg

Editura: Del Rey Books

ISBN-10: 034544258X

Pagini: 333

Dimensiuni: 97 x 186 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.17 kg

Editura: Del Rey Books

Notă biografică

Jan Siegel is also the author of Prospero's Children. She has already lived through one lifetime--during which she traveled the world and supported herself through a variety of professions, including that of actress, barmaid, garage hand, laboratory assistant, journalist, and model. Her new life is devoted to her writing, but she also finds time to ride, ski, and attend the opera.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

FIF have known many battles, many defeats. I have been a fugitive, hiding in the hollow hills, spinning the blood-magic only in the dark. The children of the north ruled my kingdom, and the Oldest Spirit hunted me with the Hounds of Arawn, and I fled from them riding on a giant owl, over the edge of being, out of the world, out of Time, to this place that was in the very beginning. Only the great birds come here, and a few other strays who crossed the boundary in the days when the barrier between worlds was thinner, and have never returned. But the witchkind may find the way, in desperation or need, and then there is no going back, and no going forward. So I dwell here, in the cave beneath the Tree, I and another who eluded persecution or senility, beyond the reach of the past. Awaiting a new future.

This is the Ancient of Trees, older than history, older than memory—the Tree of Life, whose branches uphold Middle-Earth and whose roots reach down into the deeps of the Underworld. And maybe once it grew in an orchard behind a high wall, and the apples of Good and Evil hung from its bough. No apples hang there now, but in due season it bears other fruit. The heads of the dead, which swell and ripen on their stems until the eyes open and the lips writhe, and sap drips from each truncated gorge. We can hear them muttering sometimes, louder than the wind. And then a storm will come and shake the Tree until they fall, pounding the earth like hail, and the wild hog will follow, rooting in the heaps with its tusks, glutting itself on windfalls, and the sound of its crunching carries even to the cave below. Perhaps apples fell there, once upon a time, but the wild hog does not notice the difference, or care. All who have done evil in their lives must hang a season on that Tree, or so they say; yet who among us has not done evil, some time or other? Tell me that!

You may think this is all mere fancy, the delusions of a mind warped with age and power. Come walk with me then, under the Tree, and you will see the uneaten heads rotting on the ground, and the white grubs that crawl into each open ear and lay their eggs in the shelter of the skull, and the mouths that twitch and gape until the last of the brain has been nibbled away. I saw my sister once, hanging on a low branch. Oh, not my sister Sysselore—my sister in power, my sister in kind—I mean my blood-sister, my rival, my twin. Morgun. She ripened into beauty like a pale fruit, milky skinned, raven haired, but when her eyes opened they were cold, and bitterness dragged at her features. “You will hang here, too,” she said to me, “one day.” The heads often talk to you, whether they know you or not. I suppose talk is all they can manage. I saw another that I recognized, not so long ago. We had had great hopes of her once, but she would not listen. A famine devoured her from within. I remember she had bewitched her hair so that it grew unnaturally long, and it brushed against my brow like some clinging creeper. It was wet not with sap but with water, though we had had no rain, and her budding face, still only half-formed, had a waxy gleam like the faces of the drowned. I meant to pass by again when her eyes had opened, but I was watching the smoke to see what went on in the world, and it slipped my mind.

Time is not, where we are. I may have spent centuries staring into the spellfire, seeing the tide of life sweeping by, but there are no years to measure here: only the slow unrelenting heartbeat of the Tree. Sysselore and I grate one another with words, recycling old arguments, great debates that have long degenerated into pettiness, sharp exchanges whose edges are blunted with use. We know the pattern of every dispute. She has grown thin with wear, a skeleton scantily clad in flesh; the skin that was formerly peach-golden is pallid and threaded with visible veins, a blue webbing over her arms and throat. When she sulks, as she often does, you can see the grinning lines of her skull mocking her tight mouth. She has come a long way from that enchanted island set in the sapphire seas of her youth. Syrcé they named her then, Seersay the Wise, since Wise is an epithet more courteous than others they might have chosen, and it is always prudent to flatter the Gifted. She used to turn men into pigs, by way of amusement.

“Why pigs?” I asked her, listening to the wild hog grunting and snorting around the bole of the Tree.

“Laziness,” she said. “That was their true nature, so it took very little effort.”

She is worn thin while I have swollen with my stored-up powers like the queen of a termite mound. I save my Gift, hoarding it like misers’ gold, watching in the smoke for my time to come round again. We are two who must be three, the magic number, the coven number. Someday she will be there, the she for whom we wait, and we will steal her soul away and bind her to us, versing her in our ways, casting her in our mold, and then we will return, over the borderland into reality, and the long-lost kingdom of Logrèz will be mine at last.

She felt it only for an instant, like a cold prickling on the back of her neck: the awareness that she was being watched. Not watched in the ordinary sense or even spied on, but surveyed through occult eyes, her image dancing in a flame or refracted through a crystal prism. She didn’t know how she knew, only that it was one of many instincts lurking in the substratum of her mind, waiting their moment to nudge at her thought. Her hands tightened on the steering wheel. The sensation was gone so quickly she almost believed she might have imagined it, but her pleasure in the drive was over. For her, Yorkshire would always be haunted. “Fern—” her companion was talking to her, but she had not registered a word “—Fern, are you listening to me?”

“Yes. Sorry. What did you say?”

“If you’d been listening, you wouldn’t have to ask. I never saw you so abstracted. I was just wondering why you should want to do the deed in Yarrowdale, when you don’t even like the place.”

“I don’t dislike it: it isn’t that. It’s a tiny village miles from anywhere: short stroll to a windswept beach, short scramble to a windswept moor. You can freeze your bum off in the North Sea or go for bracing walks in frightful weather. The countryside is scenic—if you like the countryside. I’m a city girl.”

“I know. So why—?”

“Marcus, of course. He thinks Yarrowdale is quaint. Characterful village church, friendly local vicar. Anyway, it’s a good excuse not to have so many guests. You tell people you’re doing it quietly, in the country, and they aren’t offended not to be invited. And of those you do invite, lots of them won’t come. It’s too far to trek just to stay in a drafty pub and drink champagne in the rain.”

“Sounds like a song,” said Gaynor Mobberley. “Champagne in the rain.” And: “Why do you always do what Marcus wants?”

“I’m going to marry him,” Fern retorted. “I want to please him. Naturally.”

“If you were in love with him,” said Gaynor, “you wouldn’t be half so conscientious about pleasing him all the time.”

“That’s a horrible thing to say.”

“Maybe. Best friends have a special license to say horrible things, if it’s really necessary.”

“I like him,” Fern said after a long pause. “That’s much more important than love.”

“I like him, too. He’s clever and witty and very good company and quite attractive considering he’s going a bit thin on top. That doesn’t mean I want to marry him. Besides, he’s twenty years older than you.”

“Eighteen. I prefer older men. With the young ones you don’t know what they’ll look like when they hit forty. It could be a nasty shock. The older men have passed the danger point so you know the worst already.”

“Now you’re being frivolous. I just don’t understand why you can’t wait until you fall in love with someone.”

Fern gave a shivery laugh. “That’s like . . . oh, waiting for a shooting star to fall in your lap, or looking for the pot of gold at the foot of the rainbow.”

“Cynic.”

“No. I’m not a cynic. It’s simply that I accept the impossibility of romantic idealism.”

“Do you remember that time in Wales?” said her friend, harking back unfairly to college days. “Morwenna Rhys gave that party at her parents house on the bay, and we all got totally drunk, and you rushed down the beach in your best dress straight into the sea. I can still see you running through the waves, and the moonlight on the foam, and your skirt flying. You looked so wild, almost eldritch. Not my cool, sophisticated Fern.”

“Everyone has to act out of character sometimes. It’s like taking your clothes off: you feel free without your character but very naked, unprotected. Unfinished. So you get dressed again—you put on yourself—and then you know who you are.”

Gaynor appeared unconvinced, but an approaching road junction caused a diversion. Fern had forgotten the way, and they stopped to consult a map. “Who’ll be there?” Gaynor enquired when they resumed their route. “When we arrive, I mean.”

“Only my brother. I asked Abby to keep Dad in London until the day before the wedding. He’d only worry about details and get fussed, and I don’t think I could take it. I can deal with any last minute hitches. Will never fusses.”

“What’s he doing now? I haven’t seen him for years.”

“Postgrad at York. Some aspect of art history. He spends a lot of time at the house, painting weird surreal pictures and collecting even weirder friends. He loves it there. He grows marijuana in the garden and litters the place with beer cans and plays pop music full blast; our dour Yorkshire housekeeper pretends to disapprove but actually she dotes on him and cossets him to death. We still call her Mrs. Wicklow although her Christian name is Dorothy. She’s really too old to housekeep but she refuses to retire so we pay a succession of helpers for her to find fault with.”

“The old family retainer,” suggested Gaynor.

“Well . . . in a way.”

“What’s the house like?”

“Sort of gray and off-putting. Victorian architecture at its most unattractively solid. We’ve added a few mod cons but there’s only one bathroom and no central heating. We’ve always meant to sell it but somehow we never got around to it. It’s not at all comfortable.”

“Is it haunted?”

There was an appreciable pause before Fern answered.

“Not exactly,” she said.

The battle was over, and now Nature was moving in to clean up. The early evening air was not cold enough to deter the flies that gathered around the hummocks of the dead; tiny crawling things invaded the chinks between jerkin and hauberk; rats, foxes, and wolves skirted the open ground, scenting a free feast. The smaller scavengers were bolder, the larger ones stayed under cover, where the fighting had spilled into the wood and bodies sprawled on the residue of last year’s autumn. Overhead, the birds arrived in force: red kites, ravens, carrion crows, wheeling and swooping in to settle thickly on the huddled mounds. And here and there a living human scuttled from corpse to corpse, more furtive than bird or beast, plucking rings from fingers, daggers from wounds, groping among rent clothing for hidden purse or love locket.

But one figure was not furtive. She came down from the crag where she had stood to view the battle, black cloaked, head covered, long snakes of hair, raven dark, escaping from the confines of her hood. Swiftly she moved across the killing ground, pausing occasionally to peer more closely at the dead, seeking a familiar face or faces among the silent horde. Her own face remained unseen but her height, her rapid stride, her evident indifference to any lurking threat told their own tale. The looters shrank from her, skulking out of sight until she passed; a carrion crow raised its head and gave a single harsh cry, as if in greeting. The setting sun, falling beneath the cloud canopy of the afternoon, flung long shadows across the land, touching pallid brow and empty eye with reflected fire, like an illusion of life returning. And so she found one that she sought, under the first of the trees, his helmet knocked awry to leave his black curls tumbling free, his beautiful features limned with the day’s last gold. A deep thrust, probably from a broadsword, had pierced his armor and opened his belly, a side swipe had half severed his neck. She brushed his cheek with the white smooth fingertips of one who has never spun, nor cooked, nor washed her clothes. “You were impatient, as always,” she said, and if there was regret in her voice, it was without tears. “You acted too soon. Folly. Folly and waste! If you had waited, all Britain would be under my hand.” There was no one nearby to hear her, yet the birds ceased their gorging at her words, and the very buzzing of the flies was stilled.

Then she straightened up, and moved away into the wood. The lake lay ahead of her, gleaming between the trees. The rocky slopes beyond and the molten chasm of sunset between cloud and hill were reflected without a quiver in its unwrinkled surface. She paced the shore, searching. Presently she found a cushion of moss darkly stained, as if something had lain and bled there; a torn cloak was abandoned nearby, a dented shield, a crowned helm. The woman picked up the crown, twisting and turning it in her hands. Then she went to the lake’s edge and peered down, muttering secret words in an ancient tongue. A shape appeared in the water mirror, inverted, a reflection where there was nothing to reflect. A boat, moving slowly, whose doleful burden she could not see, though she could guess, and sitting in the bow a woman with hair as dark as her own. The woman smiled at her from the depths of the illusion, a sweet, triumphant smile. “He is mine now,” she said. “Dead or dying, he is mine forever.” The words were not spoken aloud, but simply arrived in the Watcher’s mind, clearer than any sound. She made a brusque gesture as if brushing something away, and the chimera vanished, leaving the lake as before.

“What of the sword?” she asked of the air and the trees; but no one answered. “Was it returned whence it came?” She gave a mirthless laugh, hollow within the hood, and lifting the crown, flung it far out across the water. It broke the smooth surface into widening ripples, and was gone.

She walked off through the wood, searching no longer, driven by some other purpose. Now the standing hills had swallowed the sunset, and dusk was snared in the branches of the trees. The shadows ran together, becoming one shadow, a darkness through which the woman strode without trip or stumble, unhesitating and unafraid. She came to a place where three trees met, tangling overhead, twig locked with twig in a wrestling match as long and slow as growth. It was a place at the heart of all wildness, deep in the wood, black with more than the nightfall. She stopped there, seeing a thickening in the darkness, the gleam of eyes without a face. “Morgus,” whispered a voice that might have been the wind in the leaves, yet the night was windless, and “Morgus” hollow as the earth’s groaning.

“What do you want of me?” she said, and even then, her tone was without fear.

“You have lost,” said the voice at the heart of the wood. “Ships are coming on the wings of storm, and the northmen with their ice-gray eyes and their snow-blond hair will sweep like winter over this island that you love. The king might have resisted them, but through your machinations he is overthrown, and the kingdom for which you schemed and murdered is broken. Your time is over. You must pass the Gate or linger in vain, clinging to old revenges, until your body withers and only your spirit remains, a thin gray ghost wailing in loneliness. I did not even have to lift my hand: you have given Britain to me.”

“I have lost a battle,” she said, “in a long war. I am not yet ready to die.”

“Then live.” The voice was gentled, a murmur that seemed to come from every corner of the wood, and the night was like velvet. “Am I not Oldest and mightiest? Am I not a god in the dark? Give me your destiny and I will remold it to your heart’s desire. You will be numbered among the Serafain, the Fellangels who shadow the world with their black wings. Only submit yourself to me, and all that you dream of shall be yours.”

“He who offers to treat with the loser has won no victory,” she retorted. “I will have no truck with demon or god. Begone from this place, Old One, or try your strength against the Gift of Men. Vardé! Go back to the abyss where you were spawned! Néhaman! Envarré!”

The darkness heaved and shrank; the eye gleams slid away from her, will-o’-the-wisps that separated and flickered among the trees. She sensed an anger that flared and faded, heard an echo of cold laughter. “I do not need to destroy you, Morgus. I will leave you to destroy yourself.” And then the wood was empty, and she went on alone.

Emerging from the trees, she came to an open space where the few survivors of the conflict had begun to gather the bodies for burial, and dug a pit to accommodate them. But the grave diggers had gone, postponing their somber task till morning. A couple of torches had been left behind, thrust into the loose soil piled up by their labors; the quavering flames cast a red light that hovered uncertainly over the neighboring corpses, some shrouded in cloaks too tattered for reuse, others exposed. These were ordinary soldiers, serfs and peasants: what little armor they might have worn had been taken, even their boots were gone. Their bare feet showed the blotches of posthumous bruising. The pit itself was filled with a trembling shadow as black as ink.

Just beyond the range of the torches a figure waited, still as an animal crouched to spring. It might have been monstrous or simply grotesque; in the dark, little could be distinguished. The glancing flamelight caught a curled horn, a clawed foot, a human arm. The woman halted, staring at it, and her sudden fury was palpable.

“Are you looking for your brother? He lies elsewhere. Go sniff him out; you may get there before the ravens and the wolves have done with him. Perhaps there will be a bone or two left for you to gnaw, if it pleases you. Or do you merely wish to gloat?”

“Both,” the creature snarled. “Why not? He and his friends hunted me—when it amused them. Now he hunts with the pack of Arawn in the Gray Plains. I only hope it is his turn to play the quarry.”

“Your nature matches your face,” said she.

“As yours does not. I am as you made me, as you named me. You wanted a weapon, not a son.”

“I named you when you were unborn, when the power was great in me.” Her bitterness rasped the air like a jagged knife. “I wanted to shape your spirit into something fierce and shining, deadly as Caliburn. A vain intent. I did not get a weapon, only a burden; no warrior, but a beast. Do not tempt me with your insolence! I made you, and I may destroy you, if I choose.”

“I am flesh of your flesh,” the creature said, and the menace transformed his voice into a growl.

“You are my failure,” she snapped, “and I obliterate failure.” She raised her hand, crying a word of Command, and a lash of darkness uncoiled from her grasp and licked about the monster’s flank like a whip. He gave a howl of rage and pain, and vanished into the night.

The torches flinched and guttered. For an instant the red light danced over the cloaked shape and plunged within the cavern of the hood, and the face that sprang to life there was the face of the woman in the boat, but without the smile. Pale skinned, dark browed, with lips bitten into blood from the tension of the battle and eyes black as the Pit. For a few seconds the face hung there, glimmering in the torchlight. Then the flames died, and face and woman were gone.

They had been friends since their days at college, but Gay- nor sometimes felt that for all their closeness she knew little of her companion. Outwardly Fern Capel was smart, successful, self-assured, with a poise that more than compensated for her lack of inches, a sort of compact neatness that implied I am the right height; it is everyone else who is too tall. She had style with- out flamboyance, generosity without extravagance, an undramatic beauty, a demure sense of humor. A colleague had once said she “excelled at moderation”; yet Gaynor had witnessed Fern, on rare occasions, behaving in a way that was immoderate, even rash, her slight piquancy of feature sharpened into a disturbing wildness, an alien glitter in her eyes. At twenty-eight, she had already risen close to the top in the PR consultancy where she worked. Her fiancé, Marcus Greig, was a well-known figure of academe who had published several books and regularly aired both his knowledge and his wit in the newspapers and on television. “I plan my life,” she had told her friend, and to date everything seemed to be proceeding accordingly, smooth-running and efficient as a computer program. Or had it been “I planned my life”? Gaynor wondered, chilling at the thought, as if, in a moment of unimaginable panic and rejection, Fern had turned her back on natural disorder, on haphazard emotions, stray adventure, and had dispassionately laid down the terms for her future. Gaynor’s very soul shrank from such an idea. But on the road to Yorkshire, with the top of the car down, the citified sophisticate had blown away, leaving a girl who looked younger than her years and potentially vulnerable, and whose mood was almost fey. She doesn’t want to marry him, Gaynor concluded, seeking a simple explanation for a complex problem, but she hasn’t the courage to back out. Yet Fern had never lacked courage.

The house was a disappointment: solidly, stolidly Victorian, watching them from shadowed windows and under frowning lintels, its stoic façade apparently braced to withstand both storm and siege. “This is a house that thinks it’s a castle,” Fern said. “One of these days, I’ll have to change its mind.”

Gaynor, who assumed she was referring to some kind of designer face-lift, tried to visualize hessian curtains and terra-cotta urns, and failed.

Inside, there were notes of untidiness, a through draft from too many open windows, the incongruous blare of a radio, the clatter of approaching feet. She was introduced to Mrs. Wicklow, who appeared as grim as the house she kept, and her latest assistant, Trisha, a dumpy teenager in magenta leggings wielding a dismembered portion of a hoover. Will appeared last, lounging out of the drawing room that he had converted into a studio. The radio had evidently been turned down in his wake and the closing door suppressed its beat to a rumor. Gaynor had remembered him tall and whiplash thin but she decided his shoulders had squared, his face matured. Once he had resembled an angel with the spirit of an urchin; now she saw choirboy innocence and carnal knowledge, an imp of charm, the morality of a thief. There was a smudge of paint on his cheek that she almost fancied might have been deliberate, the conscious stigma of an artist. His summer tan turned gray eyes to blue; there were sun streaks in his hair. He greeted her as if they knew each other much better than was in fact the case, gave his sister an idle peck, and offered to help with the luggage.

“We’ve put you on the top floor,” he told Gaynor. “I hope you won’t mind. The first floor’s rather full up. If you’re lonely I’ll come and keep you company.”

“Not Alison’s room?” Fern’s voice was unexpectedly sharp.

“Of course not.”

“Who’s Alison?” Gaynor asked, but in the confusion of arrival no one found time to answer.

Her bedroom bore the unmistakable stamp of a room that had not been used in a couple of generations. It was shabbily carpeted, ruthlessly aired, the bed linen crackling with cleanliness, the ancient brocades of curtain and upholstery worn to the consistency of lichen. There was a basin and ewer on the dresser and an ugly slipware vase containing a hand-picked bunch of flowers both garden and wild. A huge mirror, bleared with recent scouring, reflected her face among the spots, and on a low table beside the bed was a large and gleaming television set. Fern surveyed it as if it were a monstrosity. “For God’s sake remove that thing,” she said to her brother. “You know it’s broken.”

“Got it fixed.” Will flashed Gaynor a grin. “This is five-star accommodation. Every modern convenience.”

“I can see that.”

But Fern still seemed inexplicably dissatisfied. As they left her to unpack, Gaynor heard her say: “You’ve put Alison’s mirror in there.”

“It’s not Alison’s mirror: it’s ours. It was just in her room.”

“She tampered with it . . .”

Gaynor left her bags on the bed and went to examine it more closely. It was the kind of mirror that makes everything look slightly gray. In it, her skin lost its color, her brown eyes were dulled, the long dark hair that was her principal glory was drained of sheen and splendor. And behind her in the depths of the glass the room appeared dim and remote, almost as if she were looking back into the past, a past beyond warmth and daylight, dingy as an unopened attic. Turning away, her attention was drawn to a charcoal sketch hanging on the wall: a woman with an Edwardian hairstyle, gazing soulfully at the flower she held in her hand. On an impulse Gaynor unhooked it, peering at the scrawl of writing across the bottom of the picture. There was an illegible signature and a name of which all she could decipher was the initial E. Not Alison, then. She put the picture back in its place and resumed her unpacking. In a miniature cabinet at her bedside she came across a pair of handkerchiefs, also embroidered with that tantalizing E. “Who was E?” she asked at dinner later on.

“Must have been one of Great-Cousin Ned’s sisters,” said Will, attacking Mrs. Wicklow’s cooking with an appetite that belied his thinness.

“Great-Cousin—?”

“He left us this house,” Fern explained. “His relationship to Daddy was so obscure we christened him Great-Cousin. It seemed logical at the time. Anyway, he had several sisters who preceded him into this world and out of it: I’m sure the youngest was an E. Esme . . . no. No. Eithne.”

“I don’t suppose there’s a romantic mystery attached to her?” Gaynor said, half-ironic, half-wistful. “Since I’ve got her room, you know.”

“No,” Fern said baldly. “There isn’t. As far as we know, she was a fluttery young girl who became a fluttery old woman, with nothing much in between. The only definite information we have is that she made seedcake that tasted of sand.”

“She must have had a lover,” Will speculated. “The family wouldn’t permit it, because he was too low class. They used to meet on the moor, like Heathcliff and Cathy only rather more restrained. He wrote bad poems for her—you’ll probably find one in your room—and she pressed the wildflower he gave her in her prayer book. That’ll be around somewhere, too. One day they were separated in a mist, she called and called to him but he did not come—he strayed too far, went over a cliff, and was lost.”

“Taken by boggarts,” Fern suggested.

“So she never married,” Will concluded, “but spent the next eighty years gradually pining away. Her sad specter still haunts the upper story, searching for whichever book it was in which she pressed that bloody flower.”

Gaynor laughed. She had been meaning to ask about Alison again, but Will’s fancy diverted her, and it slipped her mind.

It was gone midnight when they went up to bed. Gaynor slept unevenly, troubled by the country quiet, listening in her waking moments to the rumor of the wind on its way to the sea and the hooting of an owl somewhere nearby. The owl cry invaded her dreams, filling them with the noiseless flight of pale wings and the glimpse of a sad ghost face looming briefly out of the dark. She awoke before dawn, hearing the gentleness of rain on roof and windowpane. Perhaps she was still half dreaming, but it seemed to her that her window stood high in a castle wall, and outside the rain was falling softly into the dim waters of a loch, and faint and far away someone was playing the bagpipes.

In her room on the floor below, Fern, too, had heard the owl. Its eerie call drew her back from that fatal world on the other side of sleep, the world that was always waiting for her when she let go of mind and memory, leaving her spirit to roam where it would. In London she worked too hard to think and slept too deep to dream, filling the intervals of her leisure with a busy social life and the thousand distractions of the metropolis; but here on the edge of the moor there was no job, few distractions, and something in her stirred that would not be suppressed. It was here that it had all started, nearly twelve years ago. Sleep was the gateway, dream the key. She remembered a stair, a stair in a picture, and climbing the stair as it wound its way from Nowhere into Somewhere, and the tiny bright vista far ahead of a city where even the dust was golden. And then it was too late, and she was ensnared in the dream, and she could smell the heat and taste the dust, and the beat of her heart was the boom of the temple drums and the roar of the waves on the shore. “I must go back!” she cried out, trapped and desperate, but there was only one way back and her guide would not come. Never again. She had forfeited his affection, for he was of those who love jealously and will not share. Nevermore the cool smoothness of his cloud-patterned flank, nevermore the deadly luster of his horn. She ran along the empty sands looking for the sea, and then the beach turned from gold to silver and the stars crisped into foam about her feet, and she was a creature with no name to bind her and no flesh to weigh her down, the spirit that breathes in every creation and at the nucleus of all being. An emotion flowed into her that was as vivid as excitement and as deep as peace. She wanted to hold on to that moment forever, but there was a voice calling, calling her without words, dragging her back into her body and her bed, until at last she knew she was lying in the dark, and the owl’s hoot was a cry of loneliness and pain for all that she had lost.

An hour or so later she got up, took two aspirin (she would not use sleeping pills), tried to read for a while. It was a long, long time before exhaustion mastered her, and she slipped into oblivion.

Will slumbered undisturbed, accustomed to the nocturnal small talk of his nonhuman neighbors. When the bagpipes began, he merely rolled over, smiling in his sleep.

From the Hardcover edition.

This is the Ancient of Trees, older than history, older than memory—the Tree of Life, whose branches uphold Middle-Earth and whose roots reach down into the deeps of the Underworld. And maybe once it grew in an orchard behind a high wall, and the apples of Good and Evil hung from its bough. No apples hang there now, but in due season it bears other fruit. The heads of the dead, which swell and ripen on their stems until the eyes open and the lips writhe, and sap drips from each truncated gorge. We can hear them muttering sometimes, louder than the wind. And then a storm will come and shake the Tree until they fall, pounding the earth like hail, and the wild hog will follow, rooting in the heaps with its tusks, glutting itself on windfalls, and the sound of its crunching carries even to the cave below. Perhaps apples fell there, once upon a time, but the wild hog does not notice the difference, or care. All who have done evil in their lives must hang a season on that Tree, or so they say; yet who among us has not done evil, some time or other? Tell me that!

You may think this is all mere fancy, the delusions of a mind warped with age and power. Come walk with me then, under the Tree, and you will see the uneaten heads rotting on the ground, and the white grubs that crawl into each open ear and lay their eggs in the shelter of the skull, and the mouths that twitch and gape until the last of the brain has been nibbled away. I saw my sister once, hanging on a low branch. Oh, not my sister Sysselore—my sister in power, my sister in kind—I mean my blood-sister, my rival, my twin. Morgun. She ripened into beauty like a pale fruit, milky skinned, raven haired, but when her eyes opened they were cold, and bitterness dragged at her features. “You will hang here, too,” she said to me, “one day.” The heads often talk to you, whether they know you or not. I suppose talk is all they can manage. I saw another that I recognized, not so long ago. We had had great hopes of her once, but she would not listen. A famine devoured her from within. I remember she had bewitched her hair so that it grew unnaturally long, and it brushed against my brow like some clinging creeper. It was wet not with sap but with water, though we had had no rain, and her budding face, still only half-formed, had a waxy gleam like the faces of the drowned. I meant to pass by again when her eyes had opened, but I was watching the smoke to see what went on in the world, and it slipped my mind.

Time is not, where we are. I may have spent centuries staring into the spellfire, seeing the tide of life sweeping by, but there are no years to measure here: only the slow unrelenting heartbeat of the Tree. Sysselore and I grate one another with words, recycling old arguments, great debates that have long degenerated into pettiness, sharp exchanges whose edges are blunted with use. We know the pattern of every dispute. She has grown thin with wear, a skeleton scantily clad in flesh; the skin that was formerly peach-golden is pallid and threaded with visible veins, a blue webbing over her arms and throat. When she sulks, as she often does, you can see the grinning lines of her skull mocking her tight mouth. She has come a long way from that enchanted island set in the sapphire seas of her youth. Syrcé they named her then, Seersay the Wise, since Wise is an epithet more courteous than others they might have chosen, and it is always prudent to flatter the Gifted. She used to turn men into pigs, by way of amusement.

“Why pigs?” I asked her, listening to the wild hog grunting and snorting around the bole of the Tree.

“Laziness,” she said. “That was their true nature, so it took very little effort.”

She is worn thin while I have swollen with my stored-up powers like the queen of a termite mound. I save my Gift, hoarding it like misers’ gold, watching in the smoke for my time to come round again. We are two who must be three, the magic number, the coven number. Someday she will be there, the she for whom we wait, and we will steal her soul away and bind her to us, versing her in our ways, casting her in our mold, and then we will return, over the borderland into reality, and the long-lost kingdom of Logrèz will be mine at last.

She felt it only for an instant, like a cold prickling on the back of her neck: the awareness that she was being watched. Not watched in the ordinary sense or even spied on, but surveyed through occult eyes, her image dancing in a flame or refracted through a crystal prism. She didn’t know how she knew, only that it was one of many instincts lurking in the substratum of her mind, waiting their moment to nudge at her thought. Her hands tightened on the steering wheel. The sensation was gone so quickly she almost believed she might have imagined it, but her pleasure in the drive was over. For her, Yorkshire would always be haunted. “Fern—” her companion was talking to her, but she had not registered a word “—Fern, are you listening to me?”

“Yes. Sorry. What did you say?”

“If you’d been listening, you wouldn’t have to ask. I never saw you so abstracted. I was just wondering why you should want to do the deed in Yarrowdale, when you don’t even like the place.”

“I don’t dislike it: it isn’t that. It’s a tiny village miles from anywhere: short stroll to a windswept beach, short scramble to a windswept moor. You can freeze your bum off in the North Sea or go for bracing walks in frightful weather. The countryside is scenic—if you like the countryside. I’m a city girl.”

“I know. So why—?”

“Marcus, of course. He thinks Yarrowdale is quaint. Characterful village church, friendly local vicar. Anyway, it’s a good excuse not to have so many guests. You tell people you’re doing it quietly, in the country, and they aren’t offended not to be invited. And of those you do invite, lots of them won’t come. It’s too far to trek just to stay in a drafty pub and drink champagne in the rain.”

“Sounds like a song,” said Gaynor Mobberley. “Champagne in the rain.” And: “Why do you always do what Marcus wants?”

“I’m going to marry him,” Fern retorted. “I want to please him. Naturally.”

“If you were in love with him,” said Gaynor, “you wouldn’t be half so conscientious about pleasing him all the time.”

“That’s a horrible thing to say.”

“Maybe. Best friends have a special license to say horrible things, if it’s really necessary.”

“I like him,” Fern said after a long pause. “That’s much more important than love.”

“I like him, too. He’s clever and witty and very good company and quite attractive considering he’s going a bit thin on top. That doesn’t mean I want to marry him. Besides, he’s twenty years older than you.”

“Eighteen. I prefer older men. With the young ones you don’t know what they’ll look like when they hit forty. It could be a nasty shock. The older men have passed the danger point so you know the worst already.”

“Now you’re being frivolous. I just don’t understand why you can’t wait until you fall in love with someone.”

Fern gave a shivery laugh. “That’s like . . . oh, waiting for a shooting star to fall in your lap, or looking for the pot of gold at the foot of the rainbow.”

“Cynic.”

“No. I’m not a cynic. It’s simply that I accept the impossibility of romantic idealism.”

“Do you remember that time in Wales?” said her friend, harking back unfairly to college days. “Morwenna Rhys gave that party at her parents house on the bay, and we all got totally drunk, and you rushed down the beach in your best dress straight into the sea. I can still see you running through the waves, and the moonlight on the foam, and your skirt flying. You looked so wild, almost eldritch. Not my cool, sophisticated Fern.”

“Everyone has to act out of character sometimes. It’s like taking your clothes off: you feel free without your character but very naked, unprotected. Unfinished. So you get dressed again—you put on yourself—and then you know who you are.”

Gaynor appeared unconvinced, but an approaching road junction caused a diversion. Fern had forgotten the way, and they stopped to consult a map. “Who’ll be there?” Gaynor enquired when they resumed their route. “When we arrive, I mean.”

“Only my brother. I asked Abby to keep Dad in London until the day before the wedding. He’d only worry about details and get fussed, and I don’t think I could take it. I can deal with any last minute hitches. Will never fusses.”

“What’s he doing now? I haven’t seen him for years.”

“Postgrad at York. Some aspect of art history. He spends a lot of time at the house, painting weird surreal pictures and collecting even weirder friends. He loves it there. He grows marijuana in the garden and litters the place with beer cans and plays pop music full blast; our dour Yorkshire housekeeper pretends to disapprove but actually she dotes on him and cossets him to death. We still call her Mrs. Wicklow although her Christian name is Dorothy. She’s really too old to housekeep but she refuses to retire so we pay a succession of helpers for her to find fault with.”

“The old family retainer,” suggested Gaynor.

“Well . . . in a way.”

“What’s the house like?”

“Sort of gray and off-putting. Victorian architecture at its most unattractively solid. We’ve added a few mod cons but there’s only one bathroom and no central heating. We’ve always meant to sell it but somehow we never got around to it. It’s not at all comfortable.”

“Is it haunted?”

There was an appreciable pause before Fern answered.

“Not exactly,” she said.

The battle was over, and now Nature was moving in to clean up. The early evening air was not cold enough to deter the flies that gathered around the hummocks of the dead; tiny crawling things invaded the chinks between jerkin and hauberk; rats, foxes, and wolves skirted the open ground, scenting a free feast. The smaller scavengers were bolder, the larger ones stayed under cover, where the fighting had spilled into the wood and bodies sprawled on the residue of last year’s autumn. Overhead, the birds arrived in force: red kites, ravens, carrion crows, wheeling and swooping in to settle thickly on the huddled mounds. And here and there a living human scuttled from corpse to corpse, more furtive than bird or beast, plucking rings from fingers, daggers from wounds, groping among rent clothing for hidden purse or love locket.

But one figure was not furtive. She came down from the crag where she had stood to view the battle, black cloaked, head covered, long snakes of hair, raven dark, escaping from the confines of her hood. Swiftly she moved across the killing ground, pausing occasionally to peer more closely at the dead, seeking a familiar face or faces among the silent horde. Her own face remained unseen but her height, her rapid stride, her evident indifference to any lurking threat told their own tale. The looters shrank from her, skulking out of sight until she passed; a carrion crow raised its head and gave a single harsh cry, as if in greeting. The setting sun, falling beneath the cloud canopy of the afternoon, flung long shadows across the land, touching pallid brow and empty eye with reflected fire, like an illusion of life returning. And so she found one that she sought, under the first of the trees, his helmet knocked awry to leave his black curls tumbling free, his beautiful features limned with the day’s last gold. A deep thrust, probably from a broadsword, had pierced his armor and opened his belly, a side swipe had half severed his neck. She brushed his cheek with the white smooth fingertips of one who has never spun, nor cooked, nor washed her clothes. “You were impatient, as always,” she said, and if there was regret in her voice, it was without tears. “You acted too soon. Folly. Folly and waste! If you had waited, all Britain would be under my hand.” There was no one nearby to hear her, yet the birds ceased their gorging at her words, and the very buzzing of the flies was stilled.

Then she straightened up, and moved away into the wood. The lake lay ahead of her, gleaming between the trees. The rocky slopes beyond and the molten chasm of sunset between cloud and hill were reflected without a quiver in its unwrinkled surface. She paced the shore, searching. Presently she found a cushion of moss darkly stained, as if something had lain and bled there; a torn cloak was abandoned nearby, a dented shield, a crowned helm. The woman picked up the crown, twisting and turning it in her hands. Then she went to the lake’s edge and peered down, muttering secret words in an ancient tongue. A shape appeared in the water mirror, inverted, a reflection where there was nothing to reflect. A boat, moving slowly, whose doleful burden she could not see, though she could guess, and sitting in the bow a woman with hair as dark as her own. The woman smiled at her from the depths of the illusion, a sweet, triumphant smile. “He is mine now,” she said. “Dead or dying, he is mine forever.” The words were not spoken aloud, but simply arrived in the Watcher’s mind, clearer than any sound. She made a brusque gesture as if brushing something away, and the chimera vanished, leaving the lake as before.

“What of the sword?” she asked of the air and the trees; but no one answered. “Was it returned whence it came?” She gave a mirthless laugh, hollow within the hood, and lifting the crown, flung it far out across the water. It broke the smooth surface into widening ripples, and was gone.

She walked off through the wood, searching no longer, driven by some other purpose. Now the standing hills had swallowed the sunset, and dusk was snared in the branches of the trees. The shadows ran together, becoming one shadow, a darkness through which the woman strode without trip or stumble, unhesitating and unafraid. She came to a place where three trees met, tangling overhead, twig locked with twig in a wrestling match as long and slow as growth. It was a place at the heart of all wildness, deep in the wood, black with more than the nightfall. She stopped there, seeing a thickening in the darkness, the gleam of eyes without a face. “Morgus,” whispered a voice that might have been the wind in the leaves, yet the night was windless, and “Morgus” hollow as the earth’s groaning.

“What do you want of me?” she said, and even then, her tone was without fear.

“You have lost,” said the voice at the heart of the wood. “Ships are coming on the wings of storm, and the northmen with their ice-gray eyes and their snow-blond hair will sweep like winter over this island that you love. The king might have resisted them, but through your machinations he is overthrown, and the kingdom for which you schemed and murdered is broken. Your time is over. You must pass the Gate or linger in vain, clinging to old revenges, until your body withers and only your spirit remains, a thin gray ghost wailing in loneliness. I did not even have to lift my hand: you have given Britain to me.”

“I have lost a battle,” she said, “in a long war. I am not yet ready to die.”

“Then live.” The voice was gentled, a murmur that seemed to come from every corner of the wood, and the night was like velvet. “Am I not Oldest and mightiest? Am I not a god in the dark? Give me your destiny and I will remold it to your heart’s desire. You will be numbered among the Serafain, the Fellangels who shadow the world with their black wings. Only submit yourself to me, and all that you dream of shall be yours.”

“He who offers to treat with the loser has won no victory,” she retorted. “I will have no truck with demon or god. Begone from this place, Old One, or try your strength against the Gift of Men. Vardé! Go back to the abyss where you were spawned! Néhaman! Envarré!”

The darkness heaved and shrank; the eye gleams slid away from her, will-o’-the-wisps that separated and flickered among the trees. She sensed an anger that flared and faded, heard an echo of cold laughter. “I do not need to destroy you, Morgus. I will leave you to destroy yourself.” And then the wood was empty, and she went on alone.

Emerging from the trees, she came to an open space where the few survivors of the conflict had begun to gather the bodies for burial, and dug a pit to accommodate them. But the grave diggers had gone, postponing their somber task till morning. A couple of torches had been left behind, thrust into the loose soil piled up by their labors; the quavering flames cast a red light that hovered uncertainly over the neighboring corpses, some shrouded in cloaks too tattered for reuse, others exposed. These were ordinary soldiers, serfs and peasants: what little armor they might have worn had been taken, even their boots were gone. Their bare feet showed the blotches of posthumous bruising. The pit itself was filled with a trembling shadow as black as ink.

Just beyond the range of the torches a figure waited, still as an animal crouched to spring. It might have been monstrous or simply grotesque; in the dark, little could be distinguished. The glancing flamelight caught a curled horn, a clawed foot, a human arm. The woman halted, staring at it, and her sudden fury was palpable.

“Are you looking for your brother? He lies elsewhere. Go sniff him out; you may get there before the ravens and the wolves have done with him. Perhaps there will be a bone or two left for you to gnaw, if it pleases you. Or do you merely wish to gloat?”

“Both,” the creature snarled. “Why not? He and his friends hunted me—when it amused them. Now he hunts with the pack of Arawn in the Gray Plains. I only hope it is his turn to play the quarry.”

“Your nature matches your face,” said she.

“As yours does not. I am as you made me, as you named me. You wanted a weapon, not a son.”

“I named you when you were unborn, when the power was great in me.” Her bitterness rasped the air like a jagged knife. “I wanted to shape your spirit into something fierce and shining, deadly as Caliburn. A vain intent. I did not get a weapon, only a burden; no warrior, but a beast. Do not tempt me with your insolence! I made you, and I may destroy you, if I choose.”

“I am flesh of your flesh,” the creature said, and the menace transformed his voice into a growl.

“You are my failure,” she snapped, “and I obliterate failure.” She raised her hand, crying a word of Command, and a lash of darkness uncoiled from her grasp and licked about the monster’s flank like a whip. He gave a howl of rage and pain, and vanished into the night.

The torches flinched and guttered. For an instant the red light danced over the cloaked shape and plunged within the cavern of the hood, and the face that sprang to life there was the face of the woman in the boat, but without the smile. Pale skinned, dark browed, with lips bitten into blood from the tension of the battle and eyes black as the Pit. For a few seconds the face hung there, glimmering in the torchlight. Then the flames died, and face and woman were gone.

They had been friends since their days at college, but Gay- nor sometimes felt that for all their closeness she knew little of her companion. Outwardly Fern Capel was smart, successful, self-assured, with a poise that more than compensated for her lack of inches, a sort of compact neatness that implied I am the right height; it is everyone else who is too tall. She had style with- out flamboyance, generosity without extravagance, an undramatic beauty, a demure sense of humor. A colleague had once said she “excelled at moderation”; yet Gaynor had witnessed Fern, on rare occasions, behaving in a way that was immoderate, even rash, her slight piquancy of feature sharpened into a disturbing wildness, an alien glitter in her eyes. At twenty-eight, she had already risen close to the top in the PR consultancy where she worked. Her fiancé, Marcus Greig, was a well-known figure of academe who had published several books and regularly aired both his knowledge and his wit in the newspapers and on television. “I plan my life,” she had told her friend, and to date everything seemed to be proceeding accordingly, smooth-running and efficient as a computer program. Or had it been “I planned my life”? Gaynor wondered, chilling at the thought, as if, in a moment of unimaginable panic and rejection, Fern had turned her back on natural disorder, on haphazard emotions, stray adventure, and had dispassionately laid down the terms for her future. Gaynor’s very soul shrank from such an idea. But on the road to Yorkshire, with the top of the car down, the citified sophisticate had blown away, leaving a girl who looked younger than her years and potentially vulnerable, and whose mood was almost fey. She doesn’t want to marry him, Gaynor concluded, seeking a simple explanation for a complex problem, but she hasn’t the courage to back out. Yet Fern had never lacked courage.

The house was a disappointment: solidly, stolidly Victorian, watching them from shadowed windows and under frowning lintels, its stoic façade apparently braced to withstand both storm and siege. “This is a house that thinks it’s a castle,” Fern said. “One of these days, I’ll have to change its mind.”

Gaynor, who assumed she was referring to some kind of designer face-lift, tried to visualize hessian curtains and terra-cotta urns, and failed.

Inside, there were notes of untidiness, a through draft from too many open windows, the incongruous blare of a radio, the clatter of approaching feet. She was introduced to Mrs. Wicklow, who appeared as grim as the house she kept, and her latest assistant, Trisha, a dumpy teenager in magenta leggings wielding a dismembered portion of a hoover. Will appeared last, lounging out of the drawing room that he had converted into a studio. The radio had evidently been turned down in his wake and the closing door suppressed its beat to a rumor. Gaynor had remembered him tall and whiplash thin but she decided his shoulders had squared, his face matured. Once he had resembled an angel with the spirit of an urchin; now she saw choirboy innocence and carnal knowledge, an imp of charm, the morality of a thief. There was a smudge of paint on his cheek that she almost fancied might have been deliberate, the conscious stigma of an artist. His summer tan turned gray eyes to blue; there were sun streaks in his hair. He greeted her as if they knew each other much better than was in fact the case, gave his sister an idle peck, and offered to help with the luggage.

“We’ve put you on the top floor,” he told Gaynor. “I hope you won’t mind. The first floor’s rather full up. If you’re lonely I’ll come and keep you company.”

“Not Alison’s room?” Fern’s voice was unexpectedly sharp.

“Of course not.”

“Who’s Alison?” Gaynor asked, but in the confusion of arrival no one found time to answer.

Her bedroom bore the unmistakable stamp of a room that had not been used in a couple of generations. It was shabbily carpeted, ruthlessly aired, the bed linen crackling with cleanliness, the ancient brocades of curtain and upholstery worn to the consistency of lichen. There was a basin and ewer on the dresser and an ugly slipware vase containing a hand-picked bunch of flowers both garden and wild. A huge mirror, bleared with recent scouring, reflected her face among the spots, and on a low table beside the bed was a large and gleaming television set. Fern surveyed it as if it were a monstrosity. “For God’s sake remove that thing,” she said to her brother. “You know it’s broken.”

“Got it fixed.” Will flashed Gaynor a grin. “This is five-star accommodation. Every modern convenience.”

“I can see that.”

But Fern still seemed inexplicably dissatisfied. As they left her to unpack, Gaynor heard her say: “You’ve put Alison’s mirror in there.”

“It’s not Alison’s mirror: it’s ours. It was just in her room.”

“She tampered with it . . .”

Gaynor left her bags on the bed and went to examine it more closely. It was the kind of mirror that makes everything look slightly gray. In it, her skin lost its color, her brown eyes were dulled, the long dark hair that was her principal glory was drained of sheen and splendor. And behind her in the depths of the glass the room appeared dim and remote, almost as if she were looking back into the past, a past beyond warmth and daylight, dingy as an unopened attic. Turning away, her attention was drawn to a charcoal sketch hanging on the wall: a woman with an Edwardian hairstyle, gazing soulfully at the flower she held in her hand. On an impulse Gaynor unhooked it, peering at the scrawl of writing across the bottom of the picture. There was an illegible signature and a name of which all she could decipher was the initial E. Not Alison, then. She put the picture back in its place and resumed her unpacking. In a miniature cabinet at her bedside she came across a pair of handkerchiefs, also embroidered with that tantalizing E. “Who was E?” she asked at dinner later on.

“Must have been one of Great-Cousin Ned’s sisters,” said Will, attacking Mrs. Wicklow’s cooking with an appetite that belied his thinness.

“Great-Cousin—?”

“He left us this house,” Fern explained. “His relationship to Daddy was so obscure we christened him Great-Cousin. It seemed logical at the time. Anyway, he had several sisters who preceded him into this world and out of it: I’m sure the youngest was an E. Esme . . . no. No. Eithne.”

“I don’t suppose there’s a romantic mystery attached to her?” Gaynor said, half-ironic, half-wistful. “Since I’ve got her room, you know.”

“No,” Fern said baldly. “There isn’t. As far as we know, she was a fluttery young girl who became a fluttery old woman, with nothing much in between. The only definite information we have is that she made seedcake that tasted of sand.”

“She must have had a lover,” Will speculated. “The family wouldn’t permit it, because he was too low class. They used to meet on the moor, like Heathcliff and Cathy only rather more restrained. He wrote bad poems for her—you’ll probably find one in your room—and she pressed the wildflower he gave her in her prayer book. That’ll be around somewhere, too. One day they were separated in a mist, she called and called to him but he did not come—he strayed too far, went over a cliff, and was lost.”

“Taken by boggarts,” Fern suggested.

“So she never married,” Will concluded, “but spent the next eighty years gradually pining away. Her sad specter still haunts the upper story, searching for whichever book it was in which she pressed that bloody flower.”

Gaynor laughed. She had been meaning to ask about Alison again, but Will’s fancy diverted her, and it slipped her mind.

It was gone midnight when they went up to bed. Gaynor slept unevenly, troubled by the country quiet, listening in her waking moments to the rumor of the wind on its way to the sea and the hooting of an owl somewhere nearby. The owl cry invaded her dreams, filling them with the noiseless flight of pale wings and the glimpse of a sad ghost face looming briefly out of the dark. She awoke before dawn, hearing the gentleness of rain on roof and windowpane. Perhaps she was still half dreaming, but it seemed to her that her window stood high in a castle wall, and outside the rain was falling softly into the dim waters of a loch, and faint and far away someone was playing the bagpipes.

In her room on the floor below, Fern, too, had heard the owl. Its eerie call drew her back from that fatal world on the other side of sleep, the world that was always waiting for her when she let go of mind and memory, leaving her spirit to roam where it would. In London she worked too hard to think and slept too deep to dream, filling the intervals of her leisure with a busy social life and the thousand distractions of the metropolis; but here on the edge of the moor there was no job, few distractions, and something in her stirred that would not be suppressed. It was here that it had all started, nearly twelve years ago. Sleep was the gateway, dream the key. She remembered a stair, a stair in a picture, and climbing the stair as it wound its way from Nowhere into Somewhere, and the tiny bright vista far ahead of a city where even the dust was golden. And then it was too late, and she was ensnared in the dream, and she could smell the heat and taste the dust, and the beat of her heart was the boom of the temple drums and the roar of the waves on the shore. “I must go back!” she cried out, trapped and desperate, but there was only one way back and her guide would not come. Never again. She had forfeited his affection, for he was of those who love jealously and will not share. Nevermore the cool smoothness of his cloud-patterned flank, nevermore the deadly luster of his horn. She ran along the empty sands looking for the sea, and then the beach turned from gold to silver and the stars crisped into foam about her feet, and she was a creature with no name to bind her and no flesh to weigh her down, the spirit that breathes in every creation and at the nucleus of all being. An emotion flowed into her that was as vivid as excitement and as deep as peace. She wanted to hold on to that moment forever, but there was a voice calling, calling her without words, dragging her back into her body and her bed, until at last she knew she was lying in the dark, and the owl’s hoot was a cry of loneliness and pain for all that she had lost.

An hour or so later she got up, took two aspirin (she would not use sleeping pills), tried to read for a while. It was a long, long time before exhaustion mastered her, and she slipped into oblivion.

Will slumbered undisturbed, accustomed to the nocturnal small talk of his nonhuman neighbors. When the bagpipes began, he merely rolled over, smiling in his sleep.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"Jan Siegel's writing is lively, erudite, and often poetic."

--Starburst

From the Hardcover edition.

--Starburst

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

The spellbinding sequel to "Prospero's Children." Having survived a harrowing summer 12 years ago, Fern Capel renounces her mystical powers. But when she returns to her family's summer home--a place swelling with magic--ancient, sinister forces reawaken. Features a sample chapter from Siegal's August hardcover release "The Witch Queen." (August)