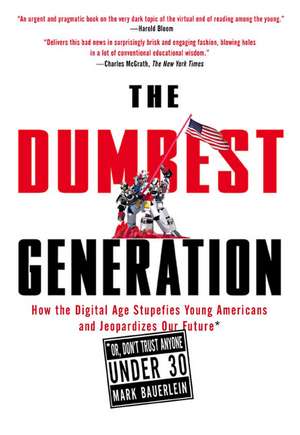

The Dumbest Generation: How the Digital Age Stupefies Young Americans and Jeopardizes Our Future (Or, Don't Trust Anyone Under 30)

Autor Mark Bauerleinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2009 – vârsta de la 18 ani

This shocking, surprisingly entertaining romp into the intellectual nether regions of today's underthirty set reveals the disturbing and, ultimately, incontrovertible truth: cyberculture is turning us into a society of know-nothings.

Preț: 99.83 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 150

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.11€ • 19.87$ • 15.77£

19.11€ • 19.87$ • 15.77£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781585427123

ISBN-10: 1585427128

Pagini: 253

Dimensiuni: 150 x 226 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Tarcher

ISBN-10: 1585427128

Pagini: 253

Dimensiuni: 150 x 226 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Tarcher

Cuprins

The Dumbest Generation Preface to the Paperback Edition

Introduction

One. Knowledge Deficits

Two. The New Bibliophobes

Three. Screen Time

Four. Online Learning and Non-Learning

Five. The Betrayal of the Mentors

Six. No More Culture Warriors

Bibliography

Index

Introduction

One. Knowledge Deficits

Two. The New Bibliophobes

Three. Screen Time

Four. Online Learning and Non-Learning

Five. The Betrayal of the Mentors

Six. No More Culture Warriors

Bibliography

Index

Recenzii

"If you're the parent of someone under 20 and read only one non-fiction book this fall, make it this one. Bauerlein's simple but jarring thesis is that technology and the digital culture it has created are not broadening the horizon of the younger generation; they are narrowing it to a self-absorbed social universe that blocks out virtually everything else."

-Don Campbell, USA Today

"An urgent and pragmatic book on the very dark topic of the virtual end of reading among the young."

-Harold Bloom

"Never have American students had it so easy, and never have they achieved less. . . . Mr. Bauerlein delivers this bad news in a surprisingly brisk and engaging fashion, blowing holes in a lot of conventional educational wisdom."

-Charles McGrath, The New York Times

"It wouldn't be going too far to call this book the Why Johnny Can't Read for the digital age."

-Booklist

"Throughout The Dumbest Generation, there are . . . keen insights into how the new digital world really is changing the way young people engage with information and the obstacles they face in integrating any of it meaningfully. These are insights that educators, parents, and other adults ignore at their peril."

-Lee Drutman, Los Angeles Times

-Don Campbell, USA Today

"An urgent and pragmatic book on the very dark topic of the virtual end of reading among the young."

-Harold Bloom

"Never have American students had it so easy, and never have they achieved less. . . . Mr. Bauerlein delivers this bad news in a surprisingly brisk and engaging fashion, blowing holes in a lot of conventional educational wisdom."

-Charles McGrath, The New York Times

"It wouldn't be going too far to call this book the Why Johnny Can't Read for the digital age."

-Booklist

"Throughout The Dumbest Generation, there are . . . keen insights into how the new digital world really is changing the way young people engage with information and the obstacles they face in integrating any of it meaningfully. These are insights that educators, parents, and other adults ignore at their peril."

-Lee Drutman, Los Angeles Times

Notă biografică

Mark Bauerlein is a professor of English at Emory University and has worked as a director of Research and Analysis at the National Endowment for the Arts, where he oversaw studies about culture and American life. He lives with his family in Atlanta.

Extras

When writer Alexandra Robbins returned to Walt Whitman High School in Bethesda, Maryland, ten years after graduating, she discovered an awful trend. The kids were miserable. She remembers her high school years as a grind of study and homework, but lots more, too, including leisure times that allowed for "well-roundedness." Not for Whitman students circa 2005. The teens in The Overachievers, Robbins's chronicle of a year spent among them, have only one thing on their minds, SUCCESS, and one thing in their hearts, ANXIETY. Trapped in a mad "culture of over-achieverism," they run a frantic race to earn an A in every class, score 750 or higher on the SATs, take piano lessons, chalk up AP courses on their transcripts, stay in shape, please their parents, volunteer for outreach programs, and, most of all, win entrance to "HYP" (Harvard-Yale-Princeton).

As graduation approaches, their résumés lengthen and sparkle, but their spirits flag and sicken. One Whitman junior, labeled by Robbins "The Stealth Overachiever," receives a fantastic 2380 (out of 2400) on a PSAT test, but instead of rejoicing, he worries that the company administering the practice run "made the diagnostics easier so students would think the class was working."

Audrey, "The Perfectionist," struggles for weeks to complete her toothpick bridge, which she and her partner expect will win them a spot in the Physics Olympics. She's one of the Young Democrats, too, and she does catering jobs. Her motivation stands out, and she thinks every other student competes with her personally, so whenever she receives a graded test or paper, "she [turns] it over without looking at it and then [puts] it away, resolving not to check the grade until she [gets] home."

"AP Frank" became a Whitman legend when as a junior he managed a "seven-AP course load that had him studying every afternoon, sleeping during class, and going lunchless." When he scored 1570 on the SAT, his domineering mother screamed in dismay, and her shock subsided only when he retook it and got the perfect 1600.

Julie, "The Superstar," has five AP classes and an internship three times a week at a museum, and she runs cross-country as well. Every evening after dinner she descends to the "homework cave" until bedtime and beyond. She got "only" 1410 on the SAT, though, and she wonders where it will land her next fall.

These kids have descended into a "competitive frenzy," Robbins mourns, and the high school that should open their minds and develop their characters has become a torture zone, a "hotbed for Machiavellian strategy." They bargain and bully and suck up for better grades. They pay tutors and coaches enormous sums to raise their scores a few points and help with the admissions process. Parents hover and query, and they schedule their children down to the minute. Grade inflation only makes it worse, an A- average now a stigma, not an accomplishment. They can't relax, they can't play. It's killing them, throwing sensitive and intelligent teenagers into pathologies of guilt and despair. The professional rat race of yore—men in gray flannel suits climbing the business ladder—has filtered down into the pre-college years, and Robbins's tormented subjects reveal the consequences.

The achievement chase displaces other life questions, and the kids can't seem to escape it. When David Brooks toured Princeton and interviewed students back in 2001, he heard of joyless days and nights with no room for newspapers or politics or dating, just "one skill-enhancing activity to the next." He calls them "Organization Kids" (after the old Organization Man figure of the fifties), students who "have to schedule appointment times for chatting." They've been programmed for success, and a preschool-to-college gauntlet of standardized tests, mounting homework, motivational messages, and extracurricular tasks has rewarded or punished them at every stage. The system tabulates learning incessantly and ranks students against one another, and the students soon divine its essence: only results matter. Education writer Alfie Kohn summarizes their logical adjustment:

Consider a school that constantly emphasizes the importance of performance! results! achievement! success! A student who has absorbed that message may find it difficult to get swept away by the process of creating a poem or trying to build a working telescope. He may be so concerned about the results that he's not at all that engaged in the activity that produces those results.

Just get the grades, they tell themselves, ace the test, study, study, study. Assignments become exercises to complete, like doing the dishes, not knowledge to acquire for the rest of their lives. The inner life fades; only the external credits count. After-school hours used to mean sports and comic books and hanging out. Now, they spell homework. As the president of the American Association of School Librarians told the Washington Post, "When kids are in school now, the stakes are so high, and they have so much homework that it's really hard to find time for pleasure reading" (see Strauss). Homework itself has become a plague, as recent titles on the subject show:

The End of Homework: How Homework Disrupts Families, Overburdens Children, and Limits Learning (Etta Kralovec and John Buell); The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing (Alfie Kohn); and The Case Against Homework: How Homework Is Hurting Our Children and What We Can Do About It (Sara Bennett and Nancy Kalish).

Parents, teachers, media, and the kids themselves witness the dangers, but the system presses forward. "We believe that reform in homework practices is central to a politics of family and personal liberation," Kralovec and Buell announce, but the momentum is too strong. The overachievement culture, results-obsessed parents, out-comes-based norms…; they continue to brutalize kids and land concerned observers such as Robbins on the Today show. Testing goes on, homework piles up, and competition for spaces in the Ivies was stiffer in 2007 than ever before. A 2006 survey by Pew Research, for instance, found that more than half the adults in the United States (56 percent) think that parents place too little pressure on students, and only 15 percent stated "Too much."

Why?

Because something is wrong with this picture, and most people realize it. They sense what the critics do not, a fundamental error in the vignettes of hyperstudious and overworked kids that we've just seen: they don't tell the truth, not the whole truth about youth in America. For, notwithstanding the poignant tale of suburban D.C. seniors sweating over a calculus quiz, or the image of college students scheduling their friends as if they were CEOs in the middle of a workday, or the lurid complaints about homework, the actual habits of most teenagers and young adults in most schools and colleges in this country display a wholly contrasting problem, but one no less disturbing.

Consider a measure of homework time, this one not taken from a dozen kids on their uneven way to the top, but from 81,499 students in 110 schools in 26 states—the 2006 High School Survey of Student Engagement. When asked how many hours they spent each week "Reading/studying for class," almost all of them, fully 90 percent, came in at a ridiculously low five hours or less, 55 percent at one hour or less. Meanwhile, 31 percent admitted to watching television or playing video games at least six hours per week, 25 percent of them logging six hours minimum surfing and chatting online.

Or check a 2004 report by the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research entitled Changing Times of American Youth: 1981–2003, which surveyed more than 2,000 families with children age six to 17 in the home. In 2003, homework time for 15- to 17year-olds hit only 24 minutes on weekend days, 50 minutes on weekdays. And weekday TV time? More than twice that: one hour, 55 minutes.

Or check a report by the U.S. Department of Education entitled NAEP 2004 Trends in Academic Progress. Among other things, the report gathered data on study and reading time for thousands of 17year-olds in 2004. When asked how many hours they'd spent on homework the day before, the tallies were meager. Fully 26 percent said that they didn't have any homework to do, while 13 percent admitted that they didn't do any of the homework they were supposed to. A little more than one-quarter (28 percent) spent less than an hour, and another 22 percent devoted one to two hours, leaving only 11 percent to pass the two-hour mark.

Or the 2004–05 State of Our Nation's Youth report by the Horatio Alger Association, in which 60 percent of teenage students logged five hours of homework per week or less.

The better students don't improve with time, either. In the 2006 National Survey of Student Engagement, a college counterpart to the High School Survey of Student Engagement, seniors in college logged some astonishingly low commitments to "Preparing for class." Almost one out of five (18 percent) stood at one to five hours per week, and 26 percent at six to ten hours per week. College professors estimate that a successful semester requires about 25 hours of out-of-class study per week, but only 11 percent reached that mark. These young adults have graduated from high school, entered college, declared a major, and lasted seven semesters, but their in-class and out-of-class punch cards amount to fewer hours than a part-time job.

And as for the claim that leisure time is disappearing, the Bureau of Labor Statistics issues an annual American Time Use Survey that asks up to 21,000 people to record their activities during the day. The categories include work and school and child care, and also leisure hours. For 2005, 15- to 24-year-olds enjoyed a full five and a half hours of free time per day, more than two hours of which they passed in front of the TV.

The findings of these and many other large surveys refute the frantic and partial renditions of youth habits and achievement that all too often make headlines and fill talk shows. Savvier observers guard against the "we're overworking the kids" alarm, people such as Jay Mathews, education reporter at the Washington Post, who called Robbins's book a "spreading delusion," and Tom Loveless of the Brookings Institution, whose 2003 report on homework said of the "homework is destroying childhood" argument, "Almost everything in this story is wrong." One correspondent's encounter with a dozen elite students who hunt success can be vivid and touching, but it doesn't jibe with mountains of data that tell contrary stories. The surveys, studies, tests, and testimonials reveal the opposite, that the vast majority of high school and college kids are far less accomplished and engaged, and the classroom pressures much less cumbersome, than popular versions put forth. These depressing accounts issue from government agencies with no ax to grind, from business leaders who just want competent workers, and from foundations that sympathize with the young. While they lack the human drama, they impart more reliable assessments, providing a better baseline for understanding the realities of the young American mentality and forcing us to stop upgrading the adolescent condition beyond its due.

This book is an attempt to consolidate the best and broadest research into a different profile of the rising American mind. It doesn't cover behaviors and values, only the intellect of under-30-year-olds. Their political leanings don't matter, nor do their career ambitions. The manners, music, clothing, speech, sexuality, faith, diversity, depression, criminality, drug use, moral codes, and celebrities of the young spark many books, articles, research papers, and marketing strategies centered on Generation Y (or Generation DotNet, or the Millennials), but not this one. It sticks to one thing, the intellectual condition of young Americans, and describes it with empirical evidence, recording something hard to document but nonetheless insidious happening inside their heads. The information is scattered and underanalyzed, but once collected and compared, it charts a consistent and perilous momentum downward.

It sounds pessimistic, and many people sympathetic to youth pressures may class the chapters to follow as yet another curmudgeonly riff. Older people have complained forever about the derelictions of youth, and the "old fogy" tag puts them on the defensive. Perhaps, though, it is a healthy process in the life story of humanity for older generations to berate the younger, for young and old to relate in a vigorous competitive dialectic, with the energy and optimism of youth vying against the wisdom and realism of elders in a fruitful check of one another's worst tendencies. That's another issue, however. The conclusions here stem from a variety of completed and ongoing research projects, public and private organizations, and university professors and media centers, and they represent different cultural values and varying attitudes toward youth. It is remarkable, then, that they so often reach the same general conclusions. They disclose many trends and consequences in youth experience, but the intellectual one emerges again and again. It's an outcome not as easily noticed as a carload of teens inching down the boulevard rattling store windows with the boom-boom of a hip-hop beat, and the effect runs deeper than brand-name clothing and speech patterns. It touches the core of a young person's mind, the mental storehouse from which he draws when engaging the world. And what the sources reveal, one by one, is that a paradoxical and distressing situation is upon us.

The paradox may be put this way. We have entered the Information Age, traveled the Information Superhighway, spawned a Knowledge Economy, undergone the Digital Revolution, converted manual workers into knowledge workers, and promoted a Creative Class, and we anticipate a Conceptual Age to be. However overhyped those grand social metaphors, they signify a rising premium on knowledge and communications, and everyone from Wired magazine to Al Gore to Thomas Friedman to the Task Force on the Future of American Innovation echoes the change. When he announced the American Competitiveness Initiative in February 2006, President Bush directly linked the fate of the U.S. economy "to generating knowledge and tools upon which new technologies are developed." In a Washington Post op-ed, Bill Gates asserted, "But if we are to remain competitive, we need a workforce that consists of the world's brightest minds…; First, we must demand strong schools so that young Americans enter the workforce with the math, science and problem-solving skills they need to succeed in the knowledge economy."

And yet, while teens and young adults have absorbed digital tools into their daily lives like no other age group, while they have grown up with more knowledge and information readily at hand, taken more classes, built their own Web sites, enjoyed more libraries, bookstores, and museums in their towns and cities…; in sum, while the world has provided them extraordinary chances to gain knowledge and improve their reading/writing skills, not to mention offering financial incentives to do so, young Americans today are no more learned or skillful than their predecessors, no more knowledgeable, fluent, up-to-date, or inquisitive, except in the materials of youth culture. They don't know any more history or civics, economics or science, literature or current events. They read less on their own, both books and newspapers, and you would have to canvass a lot of college English instructors and employers before you found one who said that they compose better paragraphs. In fact, their technology skills fall well short of the common claim, too, especially when they must apply them to research and workplace tasks.

The world delivers facts and events and art and ideas as never before, but the young American mind hasn't opened. Young Americans' vices have diminished, one must acknowledge, as teens and young adults harbor fewer stereotypes and social prejudices. Also, they regard their parents more highly than they did 25 years ago. They volunteer in strong numbers, and rates of risky behaviors are dropping. Overall conduct trends are moving upward, leading a hard-edged commentator such as Kay Hymowitz to announce in "It's Morning After in America" (2004) that "pragmatic Americans have seen the damage that their decades-long fling with the sexual revolution and the transvaluation of traditional values wrought. And now, without giving up the real gains, they are earnestly knitting up their unraveled culture. It is a moment of tremendous promise." At TechCentralStation.com, James Glassman agreed enough to proclaim, "Good News! The Kids Are Alright!" Youth watchers William Strauss and Neil Howe were confident enough to subtitle their book on young Americans The Next Great Generation (2000).

And why shouldn't they? Teenagers and young adults mingle in a society of abundance, intellectual as well as material. American youth in the twenty-first century have benefited from a shower of money and goods, a bath of liberties and pleasing self-images, vibrant civic debates, political blogs, old books and masterpieces available online, traveling exhibitions, the History Channel, news feeds…; and on and on. Never have opportunities for education, learning, political action, and cultural activity been greater. All the ingredients for making an informed and intelligent citizen are in place.

But it hasn't happened. Yes, young Americans are energetic, ambitious, enterprising, and good, but their talents and interests and money thrust them not into books and ideas and history and civics, but into a whole other realm and other consciousness. A different social life and a different mental life have formed among them. Technology has bred it, but the result doesn't tally with the fulsome descriptions of digital empowerment, global awareness, and virtual communities. Instead of opening young American minds to the stores of civilization and science and politics, technology has contracted their horizon to themselves, to the social scene around them. Young people have never been so intensely mindful of and present to one another, so enabled in adolescent contact. Teen images and songs, hot gossip and games, and youth-to-youth communications no longer limited by time or space wrap them up in a generational cocoon reaching all the way into their bedrooms. The autonomy has a cost: the more they attend to themselves, the less they remember the past and envision a future. They have all the advantages of modernity and democracy, but when the gifts of life lead to social joys, not intellectual labor, the minds of the young plateau at age 18. This is happening all around us. The fonts of knowledge are everywhere, but the rising generation is camped in the desert, passing stories, pictures, tunes, and texts back and forth, living off the thrill of peer attention. Meanwhile, their intellects refuse the cultural and civic inheritance that has made us what we are up to now.

This book explains why and how, and how much, and what it means for the civic health of the United States.

As graduation approaches, their résumés lengthen and sparkle, but their spirits flag and sicken. One Whitman junior, labeled by Robbins "The Stealth Overachiever," receives a fantastic 2380 (out of 2400) on a PSAT test, but instead of rejoicing, he worries that the company administering the practice run "made the diagnostics easier so students would think the class was working."

Audrey, "The Perfectionist," struggles for weeks to complete her toothpick bridge, which she and her partner expect will win them a spot in the Physics Olympics. She's one of the Young Democrats, too, and she does catering jobs. Her motivation stands out, and she thinks every other student competes with her personally, so whenever she receives a graded test or paper, "she [turns] it over without looking at it and then [puts] it away, resolving not to check the grade until she [gets] home."

"AP Frank" became a Whitman legend when as a junior he managed a "seven-AP course load that had him studying every afternoon, sleeping during class, and going lunchless." When he scored 1570 on the SAT, his domineering mother screamed in dismay, and her shock subsided only when he retook it and got the perfect 1600.

Julie, "The Superstar," has five AP classes and an internship three times a week at a museum, and she runs cross-country as well. Every evening after dinner she descends to the "homework cave" until bedtime and beyond. She got "only" 1410 on the SAT, though, and she wonders where it will land her next fall.

These kids have descended into a "competitive frenzy," Robbins mourns, and the high school that should open their minds and develop their characters has become a torture zone, a "hotbed for Machiavellian strategy." They bargain and bully and suck up for better grades. They pay tutors and coaches enormous sums to raise their scores a few points and help with the admissions process. Parents hover and query, and they schedule their children down to the minute. Grade inflation only makes it worse, an A- average now a stigma, not an accomplishment. They can't relax, they can't play. It's killing them, throwing sensitive and intelligent teenagers into pathologies of guilt and despair. The professional rat race of yore—men in gray flannel suits climbing the business ladder—has filtered down into the pre-college years, and Robbins's tormented subjects reveal the consequences.

The achievement chase displaces other life questions, and the kids can't seem to escape it. When David Brooks toured Princeton and interviewed students back in 2001, he heard of joyless days and nights with no room for newspapers or politics or dating, just "one skill-enhancing activity to the next." He calls them "Organization Kids" (after the old Organization Man figure of the fifties), students who "have to schedule appointment times for chatting." They've been programmed for success, and a preschool-to-college gauntlet of standardized tests, mounting homework, motivational messages, and extracurricular tasks has rewarded or punished them at every stage. The system tabulates learning incessantly and ranks students against one another, and the students soon divine its essence: only results matter. Education writer Alfie Kohn summarizes their logical adjustment:

Consider a school that constantly emphasizes the importance of performance! results! achievement! success! A student who has absorbed that message may find it difficult to get swept away by the process of creating a poem or trying to build a working telescope. He may be so concerned about the results that he's not at all that engaged in the activity that produces those results.

Just get the grades, they tell themselves, ace the test, study, study, study. Assignments become exercises to complete, like doing the dishes, not knowledge to acquire for the rest of their lives. The inner life fades; only the external credits count. After-school hours used to mean sports and comic books and hanging out. Now, they spell homework. As the president of the American Association of School Librarians told the Washington Post, "When kids are in school now, the stakes are so high, and they have so much homework that it's really hard to find time for pleasure reading" (see Strauss). Homework itself has become a plague, as recent titles on the subject show:

The End of Homework: How Homework Disrupts Families, Overburdens Children, and Limits Learning (Etta Kralovec and John Buell); The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing (Alfie Kohn); and The Case Against Homework: How Homework Is Hurting Our Children and What We Can Do About It (Sara Bennett and Nancy Kalish).

Parents, teachers, media, and the kids themselves witness the dangers, but the system presses forward. "We believe that reform in homework practices is central to a politics of family and personal liberation," Kralovec and Buell announce, but the momentum is too strong. The overachievement culture, results-obsessed parents, out-comes-based norms…; they continue to brutalize kids and land concerned observers such as Robbins on the Today show. Testing goes on, homework piles up, and competition for spaces in the Ivies was stiffer in 2007 than ever before. A 2006 survey by Pew Research, for instance, found that more than half the adults in the United States (56 percent) think that parents place too little pressure on students, and only 15 percent stated "Too much."

Why?

Because something is wrong with this picture, and most people realize it. They sense what the critics do not, a fundamental error in the vignettes of hyperstudious and overworked kids that we've just seen: they don't tell the truth, not the whole truth about youth in America. For, notwithstanding the poignant tale of suburban D.C. seniors sweating over a calculus quiz, or the image of college students scheduling their friends as if they were CEOs in the middle of a workday, or the lurid complaints about homework, the actual habits of most teenagers and young adults in most schools and colleges in this country display a wholly contrasting problem, but one no less disturbing.

Consider a measure of homework time, this one not taken from a dozen kids on their uneven way to the top, but from 81,499 students in 110 schools in 26 states—the 2006 High School Survey of Student Engagement. When asked how many hours they spent each week "Reading/studying for class," almost all of them, fully 90 percent, came in at a ridiculously low five hours or less, 55 percent at one hour or less. Meanwhile, 31 percent admitted to watching television or playing video games at least six hours per week, 25 percent of them logging six hours minimum surfing and chatting online.

Or check a 2004 report by the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research entitled Changing Times of American Youth: 1981–2003, which surveyed more than 2,000 families with children age six to 17 in the home. In 2003, homework time for 15- to 17year-olds hit only 24 minutes on weekend days, 50 minutes on weekdays. And weekday TV time? More than twice that: one hour, 55 minutes.

Or check a report by the U.S. Department of Education entitled NAEP 2004 Trends in Academic Progress. Among other things, the report gathered data on study and reading time for thousands of 17year-olds in 2004. When asked how many hours they'd spent on homework the day before, the tallies were meager. Fully 26 percent said that they didn't have any homework to do, while 13 percent admitted that they didn't do any of the homework they were supposed to. A little more than one-quarter (28 percent) spent less than an hour, and another 22 percent devoted one to two hours, leaving only 11 percent to pass the two-hour mark.

Or the 2004–05 State of Our Nation's Youth report by the Horatio Alger Association, in which 60 percent of teenage students logged five hours of homework per week or less.

The better students don't improve with time, either. In the 2006 National Survey of Student Engagement, a college counterpart to the High School Survey of Student Engagement, seniors in college logged some astonishingly low commitments to "Preparing for class." Almost one out of five (18 percent) stood at one to five hours per week, and 26 percent at six to ten hours per week. College professors estimate that a successful semester requires about 25 hours of out-of-class study per week, but only 11 percent reached that mark. These young adults have graduated from high school, entered college, declared a major, and lasted seven semesters, but their in-class and out-of-class punch cards amount to fewer hours than a part-time job.

And as for the claim that leisure time is disappearing, the Bureau of Labor Statistics issues an annual American Time Use Survey that asks up to 21,000 people to record their activities during the day. The categories include work and school and child care, and also leisure hours. For 2005, 15- to 24-year-olds enjoyed a full five and a half hours of free time per day, more than two hours of which they passed in front of the TV.

The findings of these and many other large surveys refute the frantic and partial renditions of youth habits and achievement that all too often make headlines and fill talk shows. Savvier observers guard against the "we're overworking the kids" alarm, people such as Jay Mathews, education reporter at the Washington Post, who called Robbins's book a "spreading delusion," and Tom Loveless of the Brookings Institution, whose 2003 report on homework said of the "homework is destroying childhood" argument, "Almost everything in this story is wrong." One correspondent's encounter with a dozen elite students who hunt success can be vivid and touching, but it doesn't jibe with mountains of data that tell contrary stories. The surveys, studies, tests, and testimonials reveal the opposite, that the vast majority of high school and college kids are far less accomplished and engaged, and the classroom pressures much less cumbersome, than popular versions put forth. These depressing accounts issue from government agencies with no ax to grind, from business leaders who just want competent workers, and from foundations that sympathize with the young. While they lack the human drama, they impart more reliable assessments, providing a better baseline for understanding the realities of the young American mentality and forcing us to stop upgrading the adolescent condition beyond its due.

This book is an attempt to consolidate the best and broadest research into a different profile of the rising American mind. It doesn't cover behaviors and values, only the intellect of under-30-year-olds. Their political leanings don't matter, nor do their career ambitions. The manners, music, clothing, speech, sexuality, faith, diversity, depression, criminality, drug use, moral codes, and celebrities of the young spark many books, articles, research papers, and marketing strategies centered on Generation Y (or Generation DotNet, or the Millennials), but not this one. It sticks to one thing, the intellectual condition of young Americans, and describes it with empirical evidence, recording something hard to document but nonetheless insidious happening inside their heads. The information is scattered and underanalyzed, but once collected and compared, it charts a consistent and perilous momentum downward.

It sounds pessimistic, and many people sympathetic to youth pressures may class the chapters to follow as yet another curmudgeonly riff. Older people have complained forever about the derelictions of youth, and the "old fogy" tag puts them on the defensive. Perhaps, though, it is a healthy process in the life story of humanity for older generations to berate the younger, for young and old to relate in a vigorous competitive dialectic, with the energy and optimism of youth vying against the wisdom and realism of elders in a fruitful check of one another's worst tendencies. That's another issue, however. The conclusions here stem from a variety of completed and ongoing research projects, public and private organizations, and university professors and media centers, and they represent different cultural values and varying attitudes toward youth. It is remarkable, then, that they so often reach the same general conclusions. They disclose many trends and consequences in youth experience, but the intellectual one emerges again and again. It's an outcome not as easily noticed as a carload of teens inching down the boulevard rattling store windows with the boom-boom of a hip-hop beat, and the effect runs deeper than brand-name clothing and speech patterns. It touches the core of a young person's mind, the mental storehouse from which he draws when engaging the world. And what the sources reveal, one by one, is that a paradoxical and distressing situation is upon us.

The paradox may be put this way. We have entered the Information Age, traveled the Information Superhighway, spawned a Knowledge Economy, undergone the Digital Revolution, converted manual workers into knowledge workers, and promoted a Creative Class, and we anticipate a Conceptual Age to be. However overhyped those grand social metaphors, they signify a rising premium on knowledge and communications, and everyone from Wired magazine to Al Gore to Thomas Friedman to the Task Force on the Future of American Innovation echoes the change. When he announced the American Competitiveness Initiative in February 2006, President Bush directly linked the fate of the U.S. economy "to generating knowledge and tools upon which new technologies are developed." In a Washington Post op-ed, Bill Gates asserted, "But if we are to remain competitive, we need a workforce that consists of the world's brightest minds…; First, we must demand strong schools so that young Americans enter the workforce with the math, science and problem-solving skills they need to succeed in the knowledge economy."

And yet, while teens and young adults have absorbed digital tools into their daily lives like no other age group, while they have grown up with more knowledge and information readily at hand, taken more classes, built their own Web sites, enjoyed more libraries, bookstores, and museums in their towns and cities…; in sum, while the world has provided them extraordinary chances to gain knowledge and improve their reading/writing skills, not to mention offering financial incentives to do so, young Americans today are no more learned or skillful than their predecessors, no more knowledgeable, fluent, up-to-date, or inquisitive, except in the materials of youth culture. They don't know any more history or civics, economics or science, literature or current events. They read less on their own, both books and newspapers, and you would have to canvass a lot of college English instructors and employers before you found one who said that they compose better paragraphs. In fact, their technology skills fall well short of the common claim, too, especially when they must apply them to research and workplace tasks.

The world delivers facts and events and art and ideas as never before, but the young American mind hasn't opened. Young Americans' vices have diminished, one must acknowledge, as teens and young adults harbor fewer stereotypes and social prejudices. Also, they regard their parents more highly than they did 25 years ago. They volunteer in strong numbers, and rates of risky behaviors are dropping. Overall conduct trends are moving upward, leading a hard-edged commentator such as Kay Hymowitz to announce in "It's Morning After in America" (2004) that "pragmatic Americans have seen the damage that their decades-long fling with the sexual revolution and the transvaluation of traditional values wrought. And now, without giving up the real gains, they are earnestly knitting up their unraveled culture. It is a moment of tremendous promise." At TechCentralStation.com, James Glassman agreed enough to proclaim, "Good News! The Kids Are Alright!" Youth watchers William Strauss and Neil Howe were confident enough to subtitle their book on young Americans The Next Great Generation (2000).

And why shouldn't they? Teenagers and young adults mingle in a society of abundance, intellectual as well as material. American youth in the twenty-first century have benefited from a shower of money and goods, a bath of liberties and pleasing self-images, vibrant civic debates, political blogs, old books and masterpieces available online, traveling exhibitions, the History Channel, news feeds…; and on and on. Never have opportunities for education, learning, political action, and cultural activity been greater. All the ingredients for making an informed and intelligent citizen are in place.

But it hasn't happened. Yes, young Americans are energetic, ambitious, enterprising, and good, but their talents and interests and money thrust them not into books and ideas and history and civics, but into a whole other realm and other consciousness. A different social life and a different mental life have formed among them. Technology has bred it, but the result doesn't tally with the fulsome descriptions of digital empowerment, global awareness, and virtual communities. Instead of opening young American minds to the stores of civilization and science and politics, technology has contracted their horizon to themselves, to the social scene around them. Young people have never been so intensely mindful of and present to one another, so enabled in adolescent contact. Teen images and songs, hot gossip and games, and youth-to-youth communications no longer limited by time or space wrap them up in a generational cocoon reaching all the way into their bedrooms. The autonomy has a cost: the more they attend to themselves, the less they remember the past and envision a future. They have all the advantages of modernity and democracy, but when the gifts of life lead to social joys, not intellectual labor, the minds of the young plateau at age 18. This is happening all around us. The fonts of knowledge are everywhere, but the rising generation is camped in the desert, passing stories, pictures, tunes, and texts back and forth, living off the thrill of peer attention. Meanwhile, their intellects refuse the cultural and civic inheritance that has made us what we are up to now.

This book explains why and how, and how much, and what it means for the civic health of the United States.

Descriere

A startling examination of the intellectual life of young adults, "The Dumbest Generation" reveals the disturbing, and ultimately, incontrovertible truth: cyberculture is producing a nation of know-nothings.