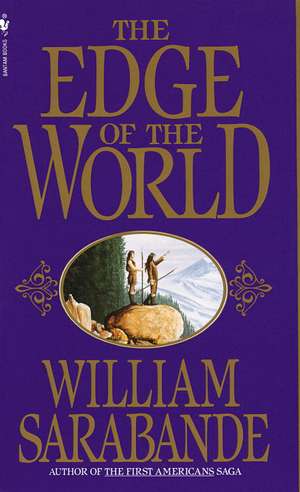

The Edge of the World: First Americans Saga

Autor William Sarabandeen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 1993

Preț: 56.00 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 84

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.72€ • 11.22$ • 8.87£

10.72€ • 11.22$ • 8.87£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553560282

ISBN-10: 055356028X

Pagini: 480

Dimensiuni: 107 x 177 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Bantam

Seria First Americans Saga

ISBN-10: 055356028X

Pagini: 480

Dimensiuni: 107 x 177 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Bantam

Seria First Americans Saga

Notă biografică

Joan Hamilton Cline is the real name of William Sarabande, author of the internationally bestselling First Americans series. She was born in Hollywood, California, and started writing when she was seventeen. First published in 1979, Joan has been writing as William Sarabande for eleven years. She lives with her husband in Fawnskin, California.

Extras

1

They came like wolves across the land. Slowly, cautiously, into the wind they came, lean men and youths painted black and red with ash and ocher and their leaner dogs, the color of storm skies and late-summer grass.

In the pure, savage light of the Ice Age noon, Cha-kwena looked down at the dog closest to him. He held no affection for its kind; nevertheless he envied it. Like the others with which it ran this day, the dog was among the best of the tribe's hunting pack, and Cha-kwena knew that it would instinctively do what was needed when the moment came to signal it into action.

May I do as well as you this day upon the hunt, Dog, brother of Wolf and Coyote! He exhaled a tight, unaudible sigh of hope and longing. For if I do not, there are those among this man pack who would have the meat of my bones roasting on the spits tonight!

Cha-kwena had not spoken aloud, but somehow the dog sensed his thoughts and turned up its head. Cha-kwena took little notice. His dark, angular eyes were now fixed on other animals.

He moved forward with the others, soundlessly insinuating himself around boulders and sidestepping loose stones. Cha-kwena was a young man, small and spare of frame, but as strong and agile and quick to react to his surroundings as the tawny little pronghorn antelope of his distant homeland. Downslope and perhaps as many as a thousand paces ahead, a small herd of striped, broad-bellied brown horses grazed at the base of high bluffs and at the neck of a dead-end draw toward which he and the other hunters had been maneuvering them since dawn.

At last we have them where we want them! Cha-kwena was so tense with anticipation, he could barely breathe. Too long have my fellow hunters gone without man-worthy meat and a kill that will make our women sing with pride! As he looked down at the horses, his youthful face split with a wide, white grin of satisfaction. Earlier in the day he had feared that the hunt might be over before it had a chance to begin. Fresh bear sign had made the horses skittish. The hunters had tethered the dogs and proceeded warily, realizing that they must not fail to walk wisely or take every precaution to remain in favor with the spirits. Otherwise they might lose the herd and themselves fall prey to a carnivore of infinitely greater and more terrifying magnitude than man.

At this moment Cha-kwena remembered that he was a shaman with a considerable reputation to maintain. With his medicine bag around his neck and his sacred owl-skin headdress securely upon his head, he reminded himself that once--and not so long before--he had led his followers to victory in a great war against their enemies. Secure in this knowledge, he uttered a special chant to Bear, reminding Walks Like a Man that if he were wise, he would avoid confrontation with so powerful a shaman as Cha-kwena of the Red World. "If you are looking for sweet roots and season-end berries and mouse tunnels to dig," he added, "you are going in the wrong direction, for the land through which my hunters now travel offers none of these."

His invocation must have been heard, for after a while the hunters lost all sign of the bear and gratefully pursued the horses into long, weather-eroded hills that were as dry and barren and creased by time as an old woman's genitals. The others called it bad land, but they continued on following the horses across country that offered nothing more threatening than rodent droppings, owl casts, and occasional mammoth spoor. Now, at last, the herd reached its destination. There were grass and water at the neck of the draw. The horses were almost within spear range. Thanks to the rocky terrain, the constancy of the wind, and the skill of the hunters in using both to their advantage, the horses detected no sight, sound, or scent of the human and canine predators that were about to make meat of them.

Cha-kwena sighed with relief. It was going to be a good day, after all! Soon the chase would be over. Soon his fellow hunters would have cause to smile at their shaman once more while they rejoiced in the taking of much meat to their hungry women and children. Then they would settle into a temporary butchering camp and rest before they began the long journey back to the village. For this Cha-kwena was supremely grateful. The overland trek had not wearied him; but his feet hurt, and he longed to take off the new moccasins that his woman had made for him. She had done something wrong with the seams, and several grass seeds had penetrated the sinew stitching to prick mercilessly at the soft skin between his ankles and the hard, thick rime of his callused heels.

Cha-kwena frowned. As soon as he returned to the village, he was going to have a serious talk with his headstrong little girl-of-a-woman about her careless workmanship. Mah-ree remained stubbornly disdainful of the complex sewing skills and customs of the People of the Land of Grass with whom the recent war had placed their little band in uneasy but beneficial alliance. Despite her status as a chieftain's daughter of the southern tribes of the distant Red World, where they had both been born, and her considerable gifts as a medicine woman, many of the hard-living northerners looked askance at her these days.

Cha-kwena's frown became a scowl under his beaked, stone-eyed headdress. It was all he could do to resist the urge to reach down and rub the soreness from his feet, but resist he did. It was dangerous for a shaman who claimed to walk strong in the power of the totem to suffer sore feet on a hunting expedition upon which everyone was depending for winter meat. If the onetime warriors from the Land of Grass lost faith in their shaman now, only the Four Winds could say what would happen to him and his small band of followers. He had led them all into this land with bold promises of a new and better life, but so far they had suffered hunger and discouragement.

Now, just ahead of Cha-kwena and slightly to his right, Shateh, leader of the hunt and warrior-chieftain of the combined bands of the People of the Land of Grass and the People of the Red World, raised his spear arm as he came to a halt. Cha-kwena stopped midstep. Everyone else did the same. No one moved. Even the dogs were frozen in place. All eyes, including Cha-kwena's, were on Shateh. Like nearly all of the hunters from the Land of Grass, the chieftain was tall and visibly powerful. The irregular vertical stripes of his body paint made him seem even larger, and his scars and graying, hip-length hair marked him as a survivor of many hunts and battles. Around his neck was a magnificent collar of golden eagle flight feathers.

Cha-kwena, forgetting all about his aching feet, positioned his bone spear hurler and long, wood-shafted, stone-tipped lances in anticipation of the kill. He could see tension in the chieftain's broad back and upraised arm. The final phase of the hunt had begun.

The young shaman held his ground as others readied their weapons and fanned out to assume prearranged positions along the high, bare, boulder-strewn ground. As shaman, his place close to Shateh was one of great prestige, and Cha-kwena knew it. The hunters were watching him now, taking slow, thoughtful measure of him from beneath lowered brows as they waited for him to begin the final invocation to the spirits of the hunt on their behalf. Whatever happened from this moment on, be it good or bad, he knew that the men would hold their shaman accountable.

Sobered by the weight of responsibility, he sent his sun-browned left hand rising to enfold the leather medicine bag that hung by a braided sinew cord around his neck. As he did so, he saw an immediate change in those around him. There was an ancient and all-transcendent magic in the sacred stone that lay within. His hand flexed around the talisman, which had been in the possession of the holy men of his band since time beyond beginning. It was a little stone, no larger than his thumb. Only its hooked shape--like a stabbing fang ripped from the mouth of a saber-toothed cat--gave any indication of its latent power. Yet all knew that the keeper of the stone walked strong and invincible in the protective power of the ancestors as he commanded the spirits of earth and sky to guide his people to victory in war and to all good things upon life's path.

Cha-kwena's hand tightened around the sacred stone. He felt neither strong nor invincible nor particularly commanding. If the hunt was to succeed, he knew he must command the forces of Creation to heed the needs of his followers. It seemed an unfair responsibility to be heaped upon one man. Resentment made him glower. He had never wanted to be shaman. By right of inheritance, through war, and because of circumstances too terrible to recall, the spirits of the ancestors had chosen him to be the one through whom they would speak to the People.

And so the sacred stone had come into his protection. Now it was his to guard with his life, just as his beloved grandfather, the old shaman Hoyeh-tay, had done before him. Many had fought and died to steal it from him and turn its powers to their own ends. All had failed . . . except Shateh.

The chieftain was looking at him now, waiting patiently for him to form his prayer upon the stone. Their eyes met and held. At one time Cha-kwena counted this man among his mortal enemies, but Shateh had chosen to stand with him in battle. Together they had broken and scattered their enemies upon the Four Winds. When Shateh had named him Brother and insisted upon uniting their two peoples, Cha-kwena had been unable to refuse. And so now Shateh claimed the sacred stone and the young shaman who went along with it, not by force but because Cha-kwena owed the chieftain his life, his loyalty, and the favor of the spirits upon at least one hunt in all these many moons.

Spirits of the stone, you must hear this man! A tremor went through Cha-kwena as he closed his eyes and raised his head high. With his medicine bag still gripped in his hand, he silently invoked the elemental spirits of all things, both animate and inanimate, and shared his hopes and fears with them. Life is hard and hungry for the people of Shateh and Cha-kwena in this new land to which war has brought us. Now our enemies are vanquished. Those who have hunted the sacred mammoth and profaned the way of the Ancient Ones have been slain. Now the people of Shateh and Cha-kwena are one. Together we keep the way of the ancestors and follow the sacred mammoth ever eastward into the face of the rising sun. But until this day the land has yielded no man-worthy meat. So you must speak to these horses! You must tell them of our hunger. You must ask them to be meat for us. Spirits of the stone, for the sake of my people, you must grant this man a good kill, or the tribesmen of Shateh will lose all trust in me and faith in your power!

"Perhaps that would not be such a bad thing?"

Cha-kwena's eyes flew open. Who had spoken? He knew that none of the hunters had asked the question. It had come from within himself or from within the sacred stone; he did not know which. The others were still watching him, waiting for him to give the signal that would tell them that his prayer for a successful hunt was complete. He stared straight ahead, unblinking and suddenly unseeing. As sometimes happened when he attempted to commune with the powers of the talisman, the intensity of his prayer shifted reality, and without warning, his mind plummeted through the labyrinthine inner corridors of perception into which only a shaman may wander. Through the vast canyons of his interior self, Cha-kwena coursed with the blood in his own veins, felt the powerful pull and push of his lungs, and heard the massive, steady drumbeat of his heart. Then the corridors of his inner vision led out of darkness as, borne on the exhalation of his own breath, he left his body and, spreading his arms wide, ascended back into reality.

With a start he saw that the other hunters were still watching him expectantly from their various positions of readiness. They were frowning, and Shateh was looking back at him, waiting and scowling. When his eyes again met those of the chieftain, a surge of awareness rushed through Cha-kwena. The chieftain was displeased with him.

"You have been too long at your prayer, Shaman!"

Cha-kwena swallowed hard. Flustered, he released his medicine bag and gave a single quick nod to indicate to the others that his invocations on their behalf had been offered. Only the Four Winds could say if they had been heard.

Shateh lowered his head in stern-eyed but otherwise expressionless acknowledgment, then turned away and gestured the others forward as he began to advance once more into the wind. Cha-kwena quickly positioned the butt end of his newest lance into the barbed end of his spear hurler and followed. The narrow, slightly arched back of the hurler rested on his right shoulder, and his stone-headed lance was at the ready, gripped between his thumb and the first two fingers of his right hand. The young shaman's heart began to race, and he found it almost impossible not to tremble with nervous excitement at the prospect of the kill and long-yearned-for feast to follow.

And then it happened. The favorite among the chieftain's three dogs was overcome by the thrill of expectation. One moment the animal was obediently walking to heel; the next, it was slobbering and whining and straining to be free of its tether. In less time than it took to draw a single breath, the chieftain smashed its skull with the blunt end of his spear, and the dog fell over dead. Shateh released the animal's tether and led his hunters on without breaking stride.

Cha-kwena stopped. Sometimes, as now, the ways of Shateh and his people stunned him. He understood that the dog had been on the verge of barking and alerting the horses to the presence of the hunters; but the cool, offhanded ease with which the chieftain had just slain the erring animal disconcerted him. Memories pricked his gut more intensely than the cursed seed coats pricked his ankles. Shateh always did what he deemed best for his tribe, no matter who or what it cost him. If the hunt did not go well today, Cha-kwena knew all too well that Shateh was capable of cutting down a favored but no longer effective shaman with the same ease that he had just displayed to slay a favorite dog.

Suddenly the wind turned. Like a viper twisting in a wooden snaking trident, it whipped around from behind and stung the bare portions of Cha-kwena's skin with airborne grit and sand carried from distant dunes and surrounding badlands. Staggered, the young man gasped from the unexpected, unseasonable cold. The wind snapped the fringes of his moccasins painfully against his lower legs, then ripped his owl-skin bonnet from his head and carried the headdress and his scent--along with the scent of every man, youth, and dog in the hunting party--to the herd of horses.

Cha-kwena sensed rather than heard the ragged exhalations of disappointment that came from those who had also been brought short by the wind. Shateh, standing just ahead of him, was shaking his spear at the sky as long, wind-whipped lengths of hair blew like tattered skeins of storm cloud before his face. Cha-kwena backhanded his own hair out of his eyes and squinted past the chieftain just in time to see the stallion raise its head and, with a shrill imperative whinny, alert its bristle-maned mares and young to imminent danger. As one, the horses, tails up, ears back, hooves ripping the earth, were off at a gallop through shallow grass. The beasts raised a cloud of grit-laden dust as they sped away from the draw and away from the hunters.

"Ay yah!" Shateh cried out in anger and frustration, his deep voice as explosive as the single stone-tipped hardwood lance loosed from his spear hurler.

Without awaiting the chieftain's command, Cha-kwena hurled a lance of his own. As a shaman who had just failed to foresee the turning of the wind on a hunt that was critical to the survival of his people, he felt obliged to do something. Never had he thrown a spear so hard. Given the distance between him and the horses, he knew his effort was a waste of a perfectly good projectile point. As it flew from his spear hurler, though, the balance and heft of the throw felt right--so right that he was not quite as amazed as every other man and youth in the party when his spear arced high over Shateh's lance to embed itself in the shoulder of one of the mares. The horse went down hard, rump over head, hooves flying skyward while the rest of the herd scattered and vanished into the eastern hills.

"Hay yah!" The cry of triumph burst from Cha-kwena's lips. The spirits of the stone had heard his prayer. "This is going to be a good day, after all!"

They came like wolves across the land. Slowly, cautiously, into the wind they came, lean men and youths painted black and red with ash and ocher and their leaner dogs, the color of storm skies and late-summer grass.

In the pure, savage light of the Ice Age noon, Cha-kwena looked down at the dog closest to him. He held no affection for its kind; nevertheless he envied it. Like the others with which it ran this day, the dog was among the best of the tribe's hunting pack, and Cha-kwena knew that it would instinctively do what was needed when the moment came to signal it into action.

May I do as well as you this day upon the hunt, Dog, brother of Wolf and Coyote! He exhaled a tight, unaudible sigh of hope and longing. For if I do not, there are those among this man pack who would have the meat of my bones roasting on the spits tonight!

Cha-kwena had not spoken aloud, but somehow the dog sensed his thoughts and turned up its head. Cha-kwena took little notice. His dark, angular eyes were now fixed on other animals.

He moved forward with the others, soundlessly insinuating himself around boulders and sidestepping loose stones. Cha-kwena was a young man, small and spare of frame, but as strong and agile and quick to react to his surroundings as the tawny little pronghorn antelope of his distant homeland. Downslope and perhaps as many as a thousand paces ahead, a small herd of striped, broad-bellied brown horses grazed at the base of high bluffs and at the neck of a dead-end draw toward which he and the other hunters had been maneuvering them since dawn.

At last we have them where we want them! Cha-kwena was so tense with anticipation, he could barely breathe. Too long have my fellow hunters gone without man-worthy meat and a kill that will make our women sing with pride! As he looked down at the horses, his youthful face split with a wide, white grin of satisfaction. Earlier in the day he had feared that the hunt might be over before it had a chance to begin. Fresh bear sign had made the horses skittish. The hunters had tethered the dogs and proceeded warily, realizing that they must not fail to walk wisely or take every precaution to remain in favor with the spirits. Otherwise they might lose the herd and themselves fall prey to a carnivore of infinitely greater and more terrifying magnitude than man.

At this moment Cha-kwena remembered that he was a shaman with a considerable reputation to maintain. With his medicine bag around his neck and his sacred owl-skin headdress securely upon his head, he reminded himself that once--and not so long before--he had led his followers to victory in a great war against their enemies. Secure in this knowledge, he uttered a special chant to Bear, reminding Walks Like a Man that if he were wise, he would avoid confrontation with so powerful a shaman as Cha-kwena of the Red World. "If you are looking for sweet roots and season-end berries and mouse tunnels to dig," he added, "you are going in the wrong direction, for the land through which my hunters now travel offers none of these."

His invocation must have been heard, for after a while the hunters lost all sign of the bear and gratefully pursued the horses into long, weather-eroded hills that were as dry and barren and creased by time as an old woman's genitals. The others called it bad land, but they continued on following the horses across country that offered nothing more threatening than rodent droppings, owl casts, and occasional mammoth spoor. Now, at last, the herd reached its destination. There were grass and water at the neck of the draw. The horses were almost within spear range. Thanks to the rocky terrain, the constancy of the wind, and the skill of the hunters in using both to their advantage, the horses detected no sight, sound, or scent of the human and canine predators that were about to make meat of them.

Cha-kwena sighed with relief. It was going to be a good day, after all! Soon the chase would be over. Soon his fellow hunters would have cause to smile at their shaman once more while they rejoiced in the taking of much meat to their hungry women and children. Then they would settle into a temporary butchering camp and rest before they began the long journey back to the village. For this Cha-kwena was supremely grateful. The overland trek had not wearied him; but his feet hurt, and he longed to take off the new moccasins that his woman had made for him. She had done something wrong with the seams, and several grass seeds had penetrated the sinew stitching to prick mercilessly at the soft skin between his ankles and the hard, thick rime of his callused heels.

Cha-kwena frowned. As soon as he returned to the village, he was going to have a serious talk with his headstrong little girl-of-a-woman about her careless workmanship. Mah-ree remained stubbornly disdainful of the complex sewing skills and customs of the People of the Land of Grass with whom the recent war had placed their little band in uneasy but beneficial alliance. Despite her status as a chieftain's daughter of the southern tribes of the distant Red World, where they had both been born, and her considerable gifts as a medicine woman, many of the hard-living northerners looked askance at her these days.

Cha-kwena's frown became a scowl under his beaked, stone-eyed headdress. It was all he could do to resist the urge to reach down and rub the soreness from his feet, but resist he did. It was dangerous for a shaman who claimed to walk strong in the power of the totem to suffer sore feet on a hunting expedition upon which everyone was depending for winter meat. If the onetime warriors from the Land of Grass lost faith in their shaman now, only the Four Winds could say what would happen to him and his small band of followers. He had led them all into this land with bold promises of a new and better life, but so far they had suffered hunger and discouragement.

Now, just ahead of Cha-kwena and slightly to his right, Shateh, leader of the hunt and warrior-chieftain of the combined bands of the People of the Land of Grass and the People of the Red World, raised his spear arm as he came to a halt. Cha-kwena stopped midstep. Everyone else did the same. No one moved. Even the dogs were frozen in place. All eyes, including Cha-kwena's, were on Shateh. Like nearly all of the hunters from the Land of Grass, the chieftain was tall and visibly powerful. The irregular vertical stripes of his body paint made him seem even larger, and his scars and graying, hip-length hair marked him as a survivor of many hunts and battles. Around his neck was a magnificent collar of golden eagle flight feathers.

Cha-kwena, forgetting all about his aching feet, positioned his bone spear hurler and long, wood-shafted, stone-tipped lances in anticipation of the kill. He could see tension in the chieftain's broad back and upraised arm. The final phase of the hunt had begun.

The young shaman held his ground as others readied their weapons and fanned out to assume prearranged positions along the high, bare, boulder-strewn ground. As shaman, his place close to Shateh was one of great prestige, and Cha-kwena knew it. The hunters were watching him now, taking slow, thoughtful measure of him from beneath lowered brows as they waited for him to begin the final invocation to the spirits of the hunt on their behalf. Whatever happened from this moment on, be it good or bad, he knew that the men would hold their shaman accountable.

Sobered by the weight of responsibility, he sent his sun-browned left hand rising to enfold the leather medicine bag that hung by a braided sinew cord around his neck. As he did so, he saw an immediate change in those around him. There was an ancient and all-transcendent magic in the sacred stone that lay within. His hand flexed around the talisman, which had been in the possession of the holy men of his band since time beyond beginning. It was a little stone, no larger than his thumb. Only its hooked shape--like a stabbing fang ripped from the mouth of a saber-toothed cat--gave any indication of its latent power. Yet all knew that the keeper of the stone walked strong and invincible in the protective power of the ancestors as he commanded the spirits of earth and sky to guide his people to victory in war and to all good things upon life's path.

Cha-kwena's hand tightened around the sacred stone. He felt neither strong nor invincible nor particularly commanding. If the hunt was to succeed, he knew he must command the forces of Creation to heed the needs of his followers. It seemed an unfair responsibility to be heaped upon one man. Resentment made him glower. He had never wanted to be shaman. By right of inheritance, through war, and because of circumstances too terrible to recall, the spirits of the ancestors had chosen him to be the one through whom they would speak to the People.

And so the sacred stone had come into his protection. Now it was his to guard with his life, just as his beloved grandfather, the old shaman Hoyeh-tay, had done before him. Many had fought and died to steal it from him and turn its powers to their own ends. All had failed . . . except Shateh.

The chieftain was looking at him now, waiting patiently for him to form his prayer upon the stone. Their eyes met and held. At one time Cha-kwena counted this man among his mortal enemies, but Shateh had chosen to stand with him in battle. Together they had broken and scattered their enemies upon the Four Winds. When Shateh had named him Brother and insisted upon uniting their two peoples, Cha-kwena had been unable to refuse. And so now Shateh claimed the sacred stone and the young shaman who went along with it, not by force but because Cha-kwena owed the chieftain his life, his loyalty, and the favor of the spirits upon at least one hunt in all these many moons.

Spirits of the stone, you must hear this man! A tremor went through Cha-kwena as he closed his eyes and raised his head high. With his medicine bag still gripped in his hand, he silently invoked the elemental spirits of all things, both animate and inanimate, and shared his hopes and fears with them. Life is hard and hungry for the people of Shateh and Cha-kwena in this new land to which war has brought us. Now our enemies are vanquished. Those who have hunted the sacred mammoth and profaned the way of the Ancient Ones have been slain. Now the people of Shateh and Cha-kwena are one. Together we keep the way of the ancestors and follow the sacred mammoth ever eastward into the face of the rising sun. But until this day the land has yielded no man-worthy meat. So you must speak to these horses! You must tell them of our hunger. You must ask them to be meat for us. Spirits of the stone, for the sake of my people, you must grant this man a good kill, or the tribesmen of Shateh will lose all trust in me and faith in your power!

"Perhaps that would not be such a bad thing?"

Cha-kwena's eyes flew open. Who had spoken? He knew that none of the hunters had asked the question. It had come from within himself or from within the sacred stone; he did not know which. The others were still watching him, waiting for him to give the signal that would tell them that his prayer for a successful hunt was complete. He stared straight ahead, unblinking and suddenly unseeing. As sometimes happened when he attempted to commune with the powers of the talisman, the intensity of his prayer shifted reality, and without warning, his mind plummeted through the labyrinthine inner corridors of perception into which only a shaman may wander. Through the vast canyons of his interior self, Cha-kwena coursed with the blood in his own veins, felt the powerful pull and push of his lungs, and heard the massive, steady drumbeat of his heart. Then the corridors of his inner vision led out of darkness as, borne on the exhalation of his own breath, he left his body and, spreading his arms wide, ascended back into reality.

With a start he saw that the other hunters were still watching him expectantly from their various positions of readiness. They were frowning, and Shateh was looking back at him, waiting and scowling. When his eyes again met those of the chieftain, a surge of awareness rushed through Cha-kwena. The chieftain was displeased with him.

"You have been too long at your prayer, Shaman!"

Cha-kwena swallowed hard. Flustered, he released his medicine bag and gave a single quick nod to indicate to the others that his invocations on their behalf had been offered. Only the Four Winds could say if they had been heard.

Shateh lowered his head in stern-eyed but otherwise expressionless acknowledgment, then turned away and gestured the others forward as he began to advance once more into the wind. Cha-kwena quickly positioned the butt end of his newest lance into the barbed end of his spear hurler and followed. The narrow, slightly arched back of the hurler rested on his right shoulder, and his stone-headed lance was at the ready, gripped between his thumb and the first two fingers of his right hand. The young shaman's heart began to race, and he found it almost impossible not to tremble with nervous excitement at the prospect of the kill and long-yearned-for feast to follow.

And then it happened. The favorite among the chieftain's three dogs was overcome by the thrill of expectation. One moment the animal was obediently walking to heel; the next, it was slobbering and whining and straining to be free of its tether. In less time than it took to draw a single breath, the chieftain smashed its skull with the blunt end of his spear, and the dog fell over dead. Shateh released the animal's tether and led his hunters on without breaking stride.

Cha-kwena stopped. Sometimes, as now, the ways of Shateh and his people stunned him. He understood that the dog had been on the verge of barking and alerting the horses to the presence of the hunters; but the cool, offhanded ease with which the chieftain had just slain the erring animal disconcerted him. Memories pricked his gut more intensely than the cursed seed coats pricked his ankles. Shateh always did what he deemed best for his tribe, no matter who or what it cost him. If the hunt did not go well today, Cha-kwena knew all too well that Shateh was capable of cutting down a favored but no longer effective shaman with the same ease that he had just displayed to slay a favorite dog.

Suddenly the wind turned. Like a viper twisting in a wooden snaking trident, it whipped around from behind and stung the bare portions of Cha-kwena's skin with airborne grit and sand carried from distant dunes and surrounding badlands. Staggered, the young man gasped from the unexpected, unseasonable cold. The wind snapped the fringes of his moccasins painfully against his lower legs, then ripped his owl-skin bonnet from his head and carried the headdress and his scent--along with the scent of every man, youth, and dog in the hunting party--to the herd of horses.

Cha-kwena sensed rather than heard the ragged exhalations of disappointment that came from those who had also been brought short by the wind. Shateh, standing just ahead of him, was shaking his spear at the sky as long, wind-whipped lengths of hair blew like tattered skeins of storm cloud before his face. Cha-kwena backhanded his own hair out of his eyes and squinted past the chieftain just in time to see the stallion raise its head and, with a shrill imperative whinny, alert its bristle-maned mares and young to imminent danger. As one, the horses, tails up, ears back, hooves ripping the earth, were off at a gallop through shallow grass. The beasts raised a cloud of grit-laden dust as they sped away from the draw and away from the hunters.

"Ay yah!" Shateh cried out in anger and frustration, his deep voice as explosive as the single stone-tipped hardwood lance loosed from his spear hurler.

Without awaiting the chieftain's command, Cha-kwena hurled a lance of his own. As a shaman who had just failed to foresee the turning of the wind on a hunt that was critical to the survival of his people, he felt obliged to do something. Never had he thrown a spear so hard. Given the distance between him and the horses, he knew his effort was a waste of a perfectly good projectile point. As it flew from his spear hurler, though, the balance and heft of the throw felt right--so right that he was not quite as amazed as every other man and youth in the party when his spear arced high over Shateh's lance to embed itself in the shoulder of one of the mares. The horse went down hard, rump over head, hooves flying skyward while the rest of the herd scattered and vanished into the eastern hills.

"Hay yah!" The cry of triumph burst from Cha-kwena's lips. The spirits of the stone had heard his prayer. "This is going to be a good day, after all!"