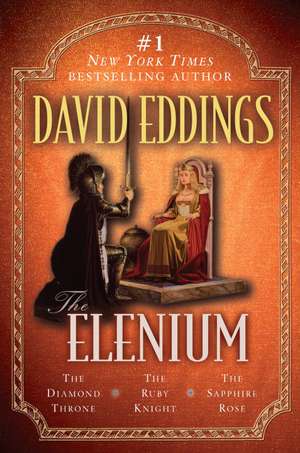

The Elenium: The Diamond, Throne the Ruby Knight, the Sapphire Rose

Autor David Eddingsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2007

In an ancient kingdom, the legacy of one royal family hangs in the balance, and the fate of a queen–and her empire–lies on the shoulders of one knight.

Sparhawk, Knight and Queen’s Champion, has returned to Elenia after ten years of exile, only to find young Queen Ehlana trapped in a crystalline cocoon. The enchantments of the sorceress Sephrenia have kept the queen alive–but the spell is fading. In the meantime, Elenia is ruled by a prince regent, the puppet of the tyrannical Annias, who vows to seize power over all the land.

Now Sparhawk must find the legendary Bhelliom, a sapphire that holds the key to Ehlana’s cure. Sparhawk and his companions will face monstrous foes and evil creatures on their journey, but even greater dangers lie in wait: for dark legions will stop at nothing to reach the radiant stone, which may possess powers too deadly for any mortal to bear.

Preț: 144.12 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 216

Preț estimativ în valută:

27.58€ • 29.49$ • 22.99£

27.58€ • 29.49$ • 22.99£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345500939

ISBN-10: 0345500938

Pagini: 902

Dimensiuni: 158 x 233 x 40 mm

Greutate: 0.88 kg

Editura: Del Rey Books

ISBN-10: 0345500938

Pagini: 902

Dimensiuni: 158 x 233 x 40 mm

Greutate: 0.88 kg

Editura: Del Rey Books

Extras

CHAPTER ONE

It was raining. A soft, silvery drizzle sifted down out of the night sky and wreathed around the blocky watchtowers of the city of Cimmura, hissing in the torches on each side of the broad gate and making the stones of the road leading up to the city shiny and black. A lone rider approached the city. He was wrapped in a dark, heavy traveller’s cloak and rode a tall, shaggy roan horse with a long nose and flat, vicious eyes. The traveller was a big man, a bigness of large, heavy bone and ropy tendon rather than of flesh. His hair was coarse and black, and at some time his nose had been broken. He rode easily, but with the peculiar alertness of the trained warrior.

His name was Sparhawk, a man at least ten years older than he looked, who carried the erosion of his years not so much on his battered face as in a half-dozen or so minor infirmities and discomforts and in the several wide purple scars upon his body which always ached in damp weather. Tonight, however, he felt his age and he wished only for a warm bed in the obscure inn which was his goal. Sparhawk was coming home at last after a decade of being someone else with a different name in a country where it almost never rained—where the sun was a hammer pounding down on a bleached white anvil of sand and rock and hard-baked clay, where the walls of the buildings were thick and white to ward off the blows of the sun, and where graceful women went to the wells in the silvery light of early morning with large clay vessels balanced on their shoulders and black veils across their faces.

The big roan horse shuddered absently, shaking the rain out of his shaggy coat, and approached the city gate, stopping in the ruddy circle of torchlight before the gatehouse.

An unshaven gate guard in a rust-splotched breastplate and helmet, and with a patched green cloak negligently hanging from one shoulder, came unsteadily out of the gatehouse and stood swaying in Sparhawk’s path. “I’ll need your name,” he said in a voice thick with drink.

Sparhawk gave him a long stare, then opened his cloak to show the heavy silver amulet hanging on a chain about his neck.

The half-drunk gate guard’s eyes widened slightly, and he stepped back a pace. “Oh,” he said, “sorry, my Lord. Go ahead.”

Another guard poked his head out of the gatehouse. “Who is he, Raf?” he demanded.

“A Pandion Knight,” the first guard replied nervously.

“What’s his business in Cimmura?”

“I don’t question the Pandions, Bral,” the man named Raf answered. He smiled ingratiatingly up at Sparhawk. “New man,” he said apologetically, jerking his thumb back over his shoulder at his comrade. “He’ll learn in time, my Lord. Can we serve you in any way?”

“No,” Sparhawk replied, “thanks all the same. You’d better get in out of the rain, neighbor. You’ll catch cold out here.” He handed a small coin to the green-cloaked guard and rode on into the city, passing up the narrow, cobbled street beyond the gate with the slow clatter of the big roan’s steel-shod hooves echoing back from the buildings.

The district near the gate was poor, with shabby, run-down houses standing tightly packed beside each other with their second floors projecting out over the wet, littered street. Crude signs swung creaking on rusty hooks in the night wind, identifying this or that tightly shuttered shop on the street-level floors. A wet, miserable-looking cur slunk across the street with his ratlike tail between his legs. Otherwise, the street was dark and empty.

A torch burned fitfully at an intersection where another street crossed the one upon which Sparhawk rode. A sick young whore, thin and wrapped in a shabby blue cloak, stood hopefully under the torch like a pale, frightened ghost. “Would you like a nice time, sir?” she whined at him. Her eyes were wide and timid, and her face gaunt and hungry.

He stopped, bent in his saddle, and poured a few small coins into her grimy hand. “Go home, little sister,” he told her in a gentle voice. “It’s late and wet, and there’ll be no customers tonight.” Then he straightened and rode on, leaving her to stare in grateful astonishment after him. He turned down a narrow side street clotted with shadow and heard the scurry of feet somewhere in the rainy dark ahead of him. His ears caught a quick, whispered conversation in the deep shadows somewhere to his left.

The roan snorted and laid his ears back.

“It’s nothing to get excited about,” Sparhawk told him. The big man’s voice was very soft, almost a husky whisper. It was the kind of voice people turned to hear. Then he spoke more loudly, addressing the pair of footpads lurking in the shadows. “I’d like to accommodate you, neighbors,” he said, “but it’s late, and I’m not in the mood for casual entertainment. Why don’t you go rob some drunk young nobleman instead, and live to steal another day?” To emphasize his words, he threw back his damp cloak to reveal the leather-bound hilt of the plain broadsword belted at his side.

There was a quick, startled silence in the dark street, followed by the rapid patter of fleeing feet.

The big roan snorted derisively.

“My sentiments exactly,” Sparhawk agreed, pulling his cloak back around him. “Shall we proceed?”

They entered a large square surrounded by hissing torches where most of the brightly colored canvas booths had their fronts rolled down. A few forlornly hopeful enthusiasts remained open for business, stridently bawling their wares to indifferent passersby hurrying home on a late, rainy evening. Sparhawk reined in his horse as a group of rowdy young nobles lurched unsteadily from the door of a seedy tavern, shouting drunkenly to each other as they crossed the square. He waited calmly until they vanished into a side street and then looked around, not so much wary as alert.

Had there been but a few more people in the nearly empty square, even Sparhawk’s trained eye might not have noticed Krager. The man was of medium height and he was rumpled and unkempt. His boots were muddy, and his maroon cape carelessly caught at the throat. He slouched across the square, his wet, colorless hair plastered down on his narrow skull and his watery eyes blinking nearsightedly as he peered about in the rain. Sparhawk drew in his breath sharply. He hadn’t seen Krager since that night in Cippria, almost ten years ago, and the man had aged considerably. His face was grayer and more pouchy-looking, but there could be no question that it was Krager.

Since quick movements attracted the eye, Sparhawk’s reaction was studied. He dismounted slowly and led his big horse to a green canvas food vendor’s stall, keeping the animal between himself and the nearsighted man in the maroon cape. “Good evening, neighbor,” he said to the brown-clad food vendor in his deadly quiet voice. “I have some business to attend to. I’ll pay you if you’ll watch my horse.”

The unshaven vendor’s eyes came quickly alight.

“Don’t even think it,” Sparhawk warned. “The horse won’t follow you, no matter what you do—but I will, and you wouldn’t like that at all. Just take the pay and forget about trying to steal the horse.”

The vendor looked at the big man’s bleak face, swallowed hard, and made a jerky attempt at a bow. “Whatever you say, my Lord,” he agreed quickly, his words tumbling over each other. “I vow to you that your noble mount will be safe with me.”

“Noble what?”

“Noble mount—your horse.”

“Oh, I see. I’d appreciate that.”

“Can I do anything else for you, my Lord?”

Sparhawk looked across the square at Krager’s back. “Do you by chance happen to have a bit of wire handy—about so long?” He measured out perhaps three feet with his hands.

“I may have, my Lord. The herring kegs are bound with wire. Let me look.”

Sparhawk crossed his arms and leaned them on his saddle, watching Krager across the horse’s back. The past years, the blasting sun, and the women going to the wells in the steely light of early morning fell away, and quite suddenly he was back in the stockyards outside Cippria with the stink of dung and blood on him, the taste of fear and hatred in his mouth, and the pain of his wounds making him weak as his pursuers searched for him with their swords in their hands.

He pulled his mind away from that, deliberately concentrating on this moment rather than the past. He hoped that the vendor could find some wire. Wire was good. No noise, no mess, and with a little time it could be made to look exotic—the kind of thing one might expect from a Styric or perhaps a Pelosian. It wasn’t so much Krager, he thought as the tense excitement built in him. Krager had never been more than a dim, feeble adjunct to Martel—an extension, another set of hands, just as the other man, Adus, had never been more than a weapon. It was what Krager’s death would do to Martel—that was what mattered.

“This is the best I could find, my Lord,” the greasy-aproned food vendor said respectfully, coming out of the back of his canvas booth and holding out a length of rusty, soft-iron wire. “I’m sorry. It isn’t much.”

“It’s just fine,” Sparhawk replied, taking the wire. He snapped the rusty strand taut between his hands. “It’s perfect, in fact.” Then he turned to his horse. “Stay here, Faran,” he said.

The horse bared his teeth at him. Sparhawk laughed softly and moved out into the square, some distance behind Krager. If the nearsighted man were found in some shadowy doorway, bowed tautly backward with the wire knotted about his neck and ankles and with his eyes popping out of a blackened face, or facedown in the trough of some back-alley public urinal, that would unnerve Martel, hurt him, perhaps even frighten him. It might be enough to bring him out into the open, and Sparhawk had been waiting for years for a chance to catch Martel out in the open. Carefully, his hands concealed beneath his cloak, he began to work the kinks out of his length of wire, even as he stalked his quarry.

His senses had become preternaturally alert. He could clearly hear the guttering of the torches along the sides of the square and see their orange flicker reflected in the puddles of water lying among the cobblestones. That reflected glow seemed for some reason very beautiful. Sparhawk felt good—better perhaps than he had for ten years.

“Sir Knight? Sir Sparhawk? Can that be you?”

Startled, Sparhawk turned quickly, swearing under his breath. The man who had accosted him had long, elegantly curled blond hair. He wore a saffron-colored doublet, lavender hose, and an apple-green cloak. His wet maroon shoes were long and pointed, and his cheeks were rouged. The small, useless sword at his side and his broadbrimmed hat with its dripping plume marked him as a courtier, one of the petty functionaries and parasitic hangers-on who infested the palace like vermin.

“What are you doing back here in Cimmura?” the fop demanded, his high-pitched, effeminate voice startled. “You were banished.”

Sparhawk looked quickly at the man he had been following. Krager was nearing the entrance to a street that opened into the square, and in a moment he would be out of sight. It was still possible, however. One quick, hard blow would put this overdressed butterfly before him to sleep, and Krager would still be within reach. Then a hot disappointment filled Sparhawk’s mouth as a detachment of the watch marched into the square with lumbering tread. There was no way now to dispose of this interfering popinjay without attracting their attention. The look he directed at the perfumed man barring his path was flat with anger.

The courtier stepped back nervously, glancing quickly at the soldiers who were moving along in front of the booths, checking the fastenings on the rolled-down canvas fronts. “I insist that you tell me what you’re doing back here,” he said, trying to sound authoritative.

“Insist? You?” Sparhawk’s voice was full of contempt.

The other man looked quickly at the soldiers again, seeking reassurance, then he straightened boldly. “I’m taking you in charge, Sparhawk. I demand that you give an account of yourself.” He reached out and grasped Sparhawk’s arm.

“Don’t touch me.” Sparhawk spat out the words, striking the hand away.

“You hit me!” the courtier gasped, clutching at his hand in pain.

Sparhawk took the man’s shoulder in one hand and pulled him close. “If you ever put your hands on me again, I’ll rip out your guts. Now get out of my way.”

“I’ll call the watch,” the fop threatened.

“And how long do you think you’ll continue to live after you do that?”

“You can’t threaten me. I have powerful friends.”

“But they’re not here, are they? I am, however.” Sparhawk pushed him away in disgust and turned to walk on across the square.

“You Pandions can’t get away with this highhanded behavior anymore. There are laws in Elenia now,” the overdressed man called after him shrilly. “I’m going straight to Baron Harparin. I’m going to tell him that you’ve come back to Cimmura and about how you hit me and threatened me.”

“Good,” Sparhawk replied without turning. “Do that.” He continued to walk away, his irritation and disappointment rising to the point where he had to clench his teeth tightly to keep himself under control. Then an idea came to him. It was petty—even childish—but for some reason it seemed quite appropriate. He stopped and straightened his shoulders, muttering under his breath in the Styric tongue, even as his fingers wove intricate designs in the air in front of him. He hesitated slightly, groping for the word for carbuncle. He finally settled for boils instead and completed the incantation. He turned slightly, looked at his tormentor, and released the spell. Then he turned back and continued on across the square, smiling slightly to himself. It was, to be sure, quite petty, but Sparhawk was like that sometimes.

He handed the food vendor a coin for minding Faran, swung up into his saddle, and rode across the square in the misty drizzle, a big man shrouded in a rough wool cloak, astride an ugly-faced roan horse.

Once he was past the square, the streets were dark and empty again, with guttering torches hissing in the rain at intersections and casting their dim, sooty orange glow. The sound of Faran’s hooves was loud in the empty street. Sparhawk shifted slightly in his saddle. The sensation he felt was very faint, a kind of prickling of the skin across his shoulders and up the back of his neck, but he recognized it immediately. Someone was watching him, and the watcher was not friendly. Sparhawk shifted again, carefully trying to make the movement appear to be no more than the uncomfortable fidgeting of a saddle-weary traveller. His right hand, however, was concealed beneath his cloak and it sought the hilt of his sword. The oppressive sense of malevolence increased, and then, in the shadows beyond the flickering torch at the next intersection, he saw a figure robed and hooded in a dark gray garment that blended so well into the shadows and wreathing drizzle that the watcher was almost invisible.

The roan tensed his muscles, and his ears flicked.

“I see him, Faran,” Sparhawk replied very quietly.

They continued on along the cobblestone street, passing through the pool of orange torchlight and on into the shadowy street beyond. Sparhawk’s eyes re- adjusted to the dark, but the hooded figure had already vanished up some alleyway or through one of the narrow doors along the street. The sense of being watched was gone, and the street was no longer a place of danger. Faran moved on, his hooves clattering on the wet stones.

The inn which was Sparhawk’s destination was on an unobtrusive back street. It was gated at the front of its central courtyard with stout oaken planks. Its walls were peculiarly high and thick, and a single, dim lantern glowed beside a much-weathered wooden sign that creaked mournfully as it swung back and forth in the rain-filled night breeze. Sparhawk pulled Faran close to the gate, leaned back in his saddle, and kicked the rain-blackened planks solidly with one spurred foot. There was a peculiar rhythm to the kicks.

He waited.

Then the gate creaked inward and the shadowy form of a porter, hooded in black, looked out. He nodded briefly, then pulled the gate wider to admit Sparhawk. The big knight rode into the rain-wet courtyard and slowly dismounted. The porter swung the gate shut and barred it, then he pushed his hood back from his steel helm, turned, and bowed. “My Lord,” he greeted Sparhawk respectfully.

“It’s too late at night for formalities, Sir Knight,” Sparhawk responded, also with a brief bow.

“Formality is the very soul of gentility, Sir Sparhawk,” the porter replied ironically. “I try to practice it whenever I can.”

“As you wish.” Sparhawk shrugged. “Will you see to my horse?”

“Of course. Your man, Kurik, is here.”

Sparhawk nodded, untying the two heavy leather bags from the skirt of his saddle.

“I’ll take those up for you, my Lord,” the porter offered.

“There’s no need. Where’s Kurik?”

“First door at the top of the stairs. Will you want supper?”

Sparhawk shook his head. “Just a bath and a warm bed.” He turned to his horse, who stood dozing with one hind leg cocked slightly so that his hoof rested on its tip. “Wake up, Faran,” he told the animal.

Faran opened his eyes and gave him a flat, unfriendly stare.

“Go with this knight,” Sparhawk instructed firmly. “Don’t try to bite him, or kick him, or pin him against the side of the stall with your rump—and don’t step on his feet, either.”

The big roan briefly laid back his ears and then sighed.

Sparhawk laughed. “Give him a few carrots,” he instructed the porter.

“How can you tolerate this foul-tempered brute, Sir Sparhawk?”

“We’re perfectly matched,” Sparhawk replied. “It was a good ride, Faran,” he said then to the horse. “Thank you, and sleep warm.”

The horse turned his back on him.

“Keep your eyes open, Sir Knight,” Sparhawk cautioned the porter. “Someone was watching me as I rode here, and I got the feeling that it was a little more than idle curiosity.”

The knight porter’s face hardened. “I’ll tend to it, my Lord,” he said.

“Good.” Sparhawk turned and crossed the wet, glistening stones of the courtyard and mounted the steps leading to the roofed gallery on the second floor of the inn.

It was raining. A soft, silvery drizzle sifted down out of the night sky and wreathed around the blocky watchtowers of the city of Cimmura, hissing in the torches on each side of the broad gate and making the stones of the road leading up to the city shiny and black. A lone rider approached the city. He was wrapped in a dark, heavy traveller’s cloak and rode a tall, shaggy roan horse with a long nose and flat, vicious eyes. The traveller was a big man, a bigness of large, heavy bone and ropy tendon rather than of flesh. His hair was coarse and black, and at some time his nose had been broken. He rode easily, but with the peculiar alertness of the trained warrior.

His name was Sparhawk, a man at least ten years older than he looked, who carried the erosion of his years not so much on his battered face as in a half-dozen or so minor infirmities and discomforts and in the several wide purple scars upon his body which always ached in damp weather. Tonight, however, he felt his age and he wished only for a warm bed in the obscure inn which was his goal. Sparhawk was coming home at last after a decade of being someone else with a different name in a country where it almost never rained—where the sun was a hammer pounding down on a bleached white anvil of sand and rock and hard-baked clay, where the walls of the buildings were thick and white to ward off the blows of the sun, and where graceful women went to the wells in the silvery light of early morning with large clay vessels balanced on their shoulders and black veils across their faces.

The big roan horse shuddered absently, shaking the rain out of his shaggy coat, and approached the city gate, stopping in the ruddy circle of torchlight before the gatehouse.

An unshaven gate guard in a rust-splotched breastplate and helmet, and with a patched green cloak negligently hanging from one shoulder, came unsteadily out of the gatehouse and stood swaying in Sparhawk’s path. “I’ll need your name,” he said in a voice thick with drink.

Sparhawk gave him a long stare, then opened his cloak to show the heavy silver amulet hanging on a chain about his neck.

The half-drunk gate guard’s eyes widened slightly, and he stepped back a pace. “Oh,” he said, “sorry, my Lord. Go ahead.”

Another guard poked his head out of the gatehouse. “Who is he, Raf?” he demanded.

“A Pandion Knight,” the first guard replied nervously.

“What’s his business in Cimmura?”

“I don’t question the Pandions, Bral,” the man named Raf answered. He smiled ingratiatingly up at Sparhawk. “New man,” he said apologetically, jerking his thumb back over his shoulder at his comrade. “He’ll learn in time, my Lord. Can we serve you in any way?”

“No,” Sparhawk replied, “thanks all the same. You’d better get in out of the rain, neighbor. You’ll catch cold out here.” He handed a small coin to the green-cloaked guard and rode on into the city, passing up the narrow, cobbled street beyond the gate with the slow clatter of the big roan’s steel-shod hooves echoing back from the buildings.

The district near the gate was poor, with shabby, run-down houses standing tightly packed beside each other with their second floors projecting out over the wet, littered street. Crude signs swung creaking on rusty hooks in the night wind, identifying this or that tightly shuttered shop on the street-level floors. A wet, miserable-looking cur slunk across the street with his ratlike tail between his legs. Otherwise, the street was dark and empty.

A torch burned fitfully at an intersection where another street crossed the one upon which Sparhawk rode. A sick young whore, thin and wrapped in a shabby blue cloak, stood hopefully under the torch like a pale, frightened ghost. “Would you like a nice time, sir?” she whined at him. Her eyes were wide and timid, and her face gaunt and hungry.

He stopped, bent in his saddle, and poured a few small coins into her grimy hand. “Go home, little sister,” he told her in a gentle voice. “It’s late and wet, and there’ll be no customers tonight.” Then he straightened and rode on, leaving her to stare in grateful astonishment after him. He turned down a narrow side street clotted with shadow and heard the scurry of feet somewhere in the rainy dark ahead of him. His ears caught a quick, whispered conversation in the deep shadows somewhere to his left.

The roan snorted and laid his ears back.

“It’s nothing to get excited about,” Sparhawk told him. The big man’s voice was very soft, almost a husky whisper. It was the kind of voice people turned to hear. Then he spoke more loudly, addressing the pair of footpads lurking in the shadows. “I’d like to accommodate you, neighbors,” he said, “but it’s late, and I’m not in the mood for casual entertainment. Why don’t you go rob some drunk young nobleman instead, and live to steal another day?” To emphasize his words, he threw back his damp cloak to reveal the leather-bound hilt of the plain broadsword belted at his side.

There was a quick, startled silence in the dark street, followed by the rapid patter of fleeing feet.

The big roan snorted derisively.

“My sentiments exactly,” Sparhawk agreed, pulling his cloak back around him. “Shall we proceed?”

They entered a large square surrounded by hissing torches where most of the brightly colored canvas booths had their fronts rolled down. A few forlornly hopeful enthusiasts remained open for business, stridently bawling their wares to indifferent passersby hurrying home on a late, rainy evening. Sparhawk reined in his horse as a group of rowdy young nobles lurched unsteadily from the door of a seedy tavern, shouting drunkenly to each other as they crossed the square. He waited calmly until they vanished into a side street and then looked around, not so much wary as alert.

Had there been but a few more people in the nearly empty square, even Sparhawk’s trained eye might not have noticed Krager. The man was of medium height and he was rumpled and unkempt. His boots were muddy, and his maroon cape carelessly caught at the throat. He slouched across the square, his wet, colorless hair plastered down on his narrow skull and his watery eyes blinking nearsightedly as he peered about in the rain. Sparhawk drew in his breath sharply. He hadn’t seen Krager since that night in Cippria, almost ten years ago, and the man had aged considerably. His face was grayer and more pouchy-looking, but there could be no question that it was Krager.

Since quick movements attracted the eye, Sparhawk’s reaction was studied. He dismounted slowly and led his big horse to a green canvas food vendor’s stall, keeping the animal between himself and the nearsighted man in the maroon cape. “Good evening, neighbor,” he said to the brown-clad food vendor in his deadly quiet voice. “I have some business to attend to. I’ll pay you if you’ll watch my horse.”

The unshaven vendor’s eyes came quickly alight.

“Don’t even think it,” Sparhawk warned. “The horse won’t follow you, no matter what you do—but I will, and you wouldn’t like that at all. Just take the pay and forget about trying to steal the horse.”

The vendor looked at the big man’s bleak face, swallowed hard, and made a jerky attempt at a bow. “Whatever you say, my Lord,” he agreed quickly, his words tumbling over each other. “I vow to you that your noble mount will be safe with me.”

“Noble what?”

“Noble mount—your horse.”

“Oh, I see. I’d appreciate that.”

“Can I do anything else for you, my Lord?”

Sparhawk looked across the square at Krager’s back. “Do you by chance happen to have a bit of wire handy—about so long?” He measured out perhaps three feet with his hands.

“I may have, my Lord. The herring kegs are bound with wire. Let me look.”

Sparhawk crossed his arms and leaned them on his saddle, watching Krager across the horse’s back. The past years, the blasting sun, and the women going to the wells in the steely light of early morning fell away, and quite suddenly he was back in the stockyards outside Cippria with the stink of dung and blood on him, the taste of fear and hatred in his mouth, and the pain of his wounds making him weak as his pursuers searched for him with their swords in their hands.

He pulled his mind away from that, deliberately concentrating on this moment rather than the past. He hoped that the vendor could find some wire. Wire was good. No noise, no mess, and with a little time it could be made to look exotic—the kind of thing one might expect from a Styric or perhaps a Pelosian. It wasn’t so much Krager, he thought as the tense excitement built in him. Krager had never been more than a dim, feeble adjunct to Martel—an extension, another set of hands, just as the other man, Adus, had never been more than a weapon. It was what Krager’s death would do to Martel—that was what mattered.

“This is the best I could find, my Lord,” the greasy-aproned food vendor said respectfully, coming out of the back of his canvas booth and holding out a length of rusty, soft-iron wire. “I’m sorry. It isn’t much.”

“It’s just fine,” Sparhawk replied, taking the wire. He snapped the rusty strand taut between his hands. “It’s perfect, in fact.” Then he turned to his horse. “Stay here, Faran,” he said.

The horse bared his teeth at him. Sparhawk laughed softly and moved out into the square, some distance behind Krager. If the nearsighted man were found in some shadowy doorway, bowed tautly backward with the wire knotted about his neck and ankles and with his eyes popping out of a blackened face, or facedown in the trough of some back-alley public urinal, that would unnerve Martel, hurt him, perhaps even frighten him. It might be enough to bring him out into the open, and Sparhawk had been waiting for years for a chance to catch Martel out in the open. Carefully, his hands concealed beneath his cloak, he began to work the kinks out of his length of wire, even as he stalked his quarry.

His senses had become preternaturally alert. He could clearly hear the guttering of the torches along the sides of the square and see their orange flicker reflected in the puddles of water lying among the cobblestones. That reflected glow seemed for some reason very beautiful. Sparhawk felt good—better perhaps than he had for ten years.

“Sir Knight? Sir Sparhawk? Can that be you?”

Startled, Sparhawk turned quickly, swearing under his breath. The man who had accosted him had long, elegantly curled blond hair. He wore a saffron-colored doublet, lavender hose, and an apple-green cloak. His wet maroon shoes were long and pointed, and his cheeks were rouged. The small, useless sword at his side and his broadbrimmed hat with its dripping plume marked him as a courtier, one of the petty functionaries and parasitic hangers-on who infested the palace like vermin.

“What are you doing back here in Cimmura?” the fop demanded, his high-pitched, effeminate voice startled. “You were banished.”

Sparhawk looked quickly at the man he had been following. Krager was nearing the entrance to a street that opened into the square, and in a moment he would be out of sight. It was still possible, however. One quick, hard blow would put this overdressed butterfly before him to sleep, and Krager would still be within reach. Then a hot disappointment filled Sparhawk’s mouth as a detachment of the watch marched into the square with lumbering tread. There was no way now to dispose of this interfering popinjay without attracting their attention. The look he directed at the perfumed man barring his path was flat with anger.

The courtier stepped back nervously, glancing quickly at the soldiers who were moving along in front of the booths, checking the fastenings on the rolled-down canvas fronts. “I insist that you tell me what you’re doing back here,” he said, trying to sound authoritative.

“Insist? You?” Sparhawk’s voice was full of contempt.

The other man looked quickly at the soldiers again, seeking reassurance, then he straightened boldly. “I’m taking you in charge, Sparhawk. I demand that you give an account of yourself.” He reached out and grasped Sparhawk’s arm.

“Don’t touch me.” Sparhawk spat out the words, striking the hand away.

“You hit me!” the courtier gasped, clutching at his hand in pain.

Sparhawk took the man’s shoulder in one hand and pulled him close. “If you ever put your hands on me again, I’ll rip out your guts. Now get out of my way.”

“I’ll call the watch,” the fop threatened.

“And how long do you think you’ll continue to live after you do that?”

“You can’t threaten me. I have powerful friends.”

“But they’re not here, are they? I am, however.” Sparhawk pushed him away in disgust and turned to walk on across the square.

“You Pandions can’t get away with this highhanded behavior anymore. There are laws in Elenia now,” the overdressed man called after him shrilly. “I’m going straight to Baron Harparin. I’m going to tell him that you’ve come back to Cimmura and about how you hit me and threatened me.”

“Good,” Sparhawk replied without turning. “Do that.” He continued to walk away, his irritation and disappointment rising to the point where he had to clench his teeth tightly to keep himself under control. Then an idea came to him. It was petty—even childish—but for some reason it seemed quite appropriate. He stopped and straightened his shoulders, muttering under his breath in the Styric tongue, even as his fingers wove intricate designs in the air in front of him. He hesitated slightly, groping for the word for carbuncle. He finally settled for boils instead and completed the incantation. He turned slightly, looked at his tormentor, and released the spell. Then he turned back and continued on across the square, smiling slightly to himself. It was, to be sure, quite petty, but Sparhawk was like that sometimes.

He handed the food vendor a coin for minding Faran, swung up into his saddle, and rode across the square in the misty drizzle, a big man shrouded in a rough wool cloak, astride an ugly-faced roan horse.

Once he was past the square, the streets were dark and empty again, with guttering torches hissing in the rain at intersections and casting their dim, sooty orange glow. The sound of Faran’s hooves was loud in the empty street. Sparhawk shifted slightly in his saddle. The sensation he felt was very faint, a kind of prickling of the skin across his shoulders and up the back of his neck, but he recognized it immediately. Someone was watching him, and the watcher was not friendly. Sparhawk shifted again, carefully trying to make the movement appear to be no more than the uncomfortable fidgeting of a saddle-weary traveller. His right hand, however, was concealed beneath his cloak and it sought the hilt of his sword. The oppressive sense of malevolence increased, and then, in the shadows beyond the flickering torch at the next intersection, he saw a figure robed and hooded in a dark gray garment that blended so well into the shadows and wreathing drizzle that the watcher was almost invisible.

The roan tensed his muscles, and his ears flicked.

“I see him, Faran,” Sparhawk replied very quietly.

They continued on along the cobblestone street, passing through the pool of orange torchlight and on into the shadowy street beyond. Sparhawk’s eyes re- adjusted to the dark, but the hooded figure had already vanished up some alleyway or through one of the narrow doors along the street. The sense of being watched was gone, and the street was no longer a place of danger. Faran moved on, his hooves clattering on the wet stones.

The inn which was Sparhawk’s destination was on an unobtrusive back street. It was gated at the front of its central courtyard with stout oaken planks. Its walls were peculiarly high and thick, and a single, dim lantern glowed beside a much-weathered wooden sign that creaked mournfully as it swung back and forth in the rain-filled night breeze. Sparhawk pulled Faran close to the gate, leaned back in his saddle, and kicked the rain-blackened planks solidly with one spurred foot. There was a peculiar rhythm to the kicks.

He waited.

Then the gate creaked inward and the shadowy form of a porter, hooded in black, looked out. He nodded briefly, then pulled the gate wider to admit Sparhawk. The big knight rode into the rain-wet courtyard and slowly dismounted. The porter swung the gate shut and barred it, then he pushed his hood back from his steel helm, turned, and bowed. “My Lord,” he greeted Sparhawk respectfully.

“It’s too late at night for formalities, Sir Knight,” Sparhawk responded, also with a brief bow.

“Formality is the very soul of gentility, Sir Sparhawk,” the porter replied ironically. “I try to practice it whenever I can.”

“As you wish.” Sparhawk shrugged. “Will you see to my horse?”

“Of course. Your man, Kurik, is here.”

Sparhawk nodded, untying the two heavy leather bags from the skirt of his saddle.

“I’ll take those up for you, my Lord,” the porter offered.

“There’s no need. Where’s Kurik?”

“First door at the top of the stairs. Will you want supper?”

Sparhawk shook his head. “Just a bath and a warm bed.” He turned to his horse, who stood dozing with one hind leg cocked slightly so that his hoof rested on its tip. “Wake up, Faran,” he told the animal.

Faran opened his eyes and gave him a flat, unfriendly stare.

“Go with this knight,” Sparhawk instructed firmly. “Don’t try to bite him, or kick him, or pin him against the side of the stall with your rump—and don’t step on his feet, either.”

The big roan briefly laid back his ears and then sighed.

Sparhawk laughed. “Give him a few carrots,” he instructed the porter.

“How can you tolerate this foul-tempered brute, Sir Sparhawk?”

“We’re perfectly matched,” Sparhawk replied. “It was a good ride, Faran,” he said then to the horse. “Thank you, and sleep warm.”

The horse turned his back on him.

“Keep your eyes open, Sir Knight,” Sparhawk cautioned the porter. “Someone was watching me as I rode here, and I got the feeling that it was a little more than idle curiosity.”

The knight porter’s face hardened. “I’ll tend to it, my Lord,” he said.

“Good.” Sparhawk turned and crossed the wet, glistening stones of the courtyard and mounted the steps leading to the roofed gallery on the second floor of the inn.