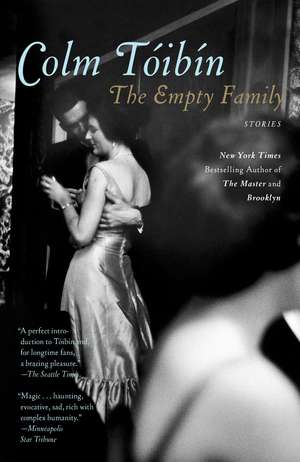

The Empty Family: Stories: Bestselling Short Stories

Autor Colm Toibinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 3 ian 2012

Critics praised Brooklyn as a “beautifully rendered portrait of Brooklyn and provincial Ireland in the 1950s.” In The Empty Family, Tóibín has extended his imagination further, offering an incredible range of periods and characters—people linked by love, loneliness, desire—“the unvarying dilemmas of the human heart” ( The Observer, UK).

In the breathtaking long story “The Street,” Tóibín imagines a relationship between Pakistani workers in Barcelona—a taboo affair in a community ruled by obedience and silence. In “Two Women,” an eminent and taciturn Irish set designer takes a job in her homeland and must confront emotions she has long repressed. “Silence” is a brilliant historical set piece about Lady Gregory, who tells the writer Henry James a confessional story at a dinner party.

The Empty Family will further cement Tóibín’s status as “his generation’s most gifted writer of love’s complicated, contradictory power” ( Los Angeles Times ).

Preț: 91.32 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 137

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.47€ • 18.29$ • 14.46£

17.47€ • 18.29$ • 14.46£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781439195963

ISBN-10: 143919596X

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Scribner

Colecția Scribner

Seria Bestselling Short Stories

ISBN-10: 143919596X

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Scribner

Colecția Scribner

Seria Bestselling Short Stories

Notă biografică

Colm Tóibín is the author of eleven novels, including Long Island, an Oprah’s Book Club Pick; The Magician, winner of the Rathbones Folio Prize; The Master, winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Prize; Brooklyn, winner of the Costa Book Award; and Nora Webster; as well as two story collections and several books of criticism. He is the Irene and Sidney B. Silverman Professor of the Humanities at Columbia University and was named the 2022–2024 Laureate for Irish Fiction by the Arts Council of Ireland. He was shortlisted three times for the Booker Prize. He was also awarded the Bodley Medal, the Würth Prize for European Literature, and the Prix Femina spécial for his body of work.

Extras

Silence

34 DVG, January 23d, 1894

Another incident—“subject”—related to me by Lady G. was that of the eminent London clergyman who on the Dover-to-Calais steamer, starting on his wedding tour, picked up on the deck a letter addressed to his wife, while she was below, and finding it to be from an old lover, and very ardent (an engagement—a rupture, a relation, in short), of which he never had been told, took the line of sending her, from Paris, straight back to her parents—without having touched her—on the ground that he had been deceived. He ended, subsequently, by taking her back into his house to live, but never lived with her as his wife. There is a drama in the various things, for her, to which that situation—that night in Paris—might have led. Her immediate surrender to some one else, etc. etc. etc.

—from The Notebooks of Henry James

Sometimes when the evening had almost ended, Lady Gregory would catch someone’s eye for a moment and that would be enough to make her remember. At those tables in the great city she knew not ever to talk about herself, or complain about anything such as the heat, or the dullness of the season, or the antics of an actress; she knew not to babble about banalities, or laugh at things that were not very funny. She focused instead with as much force and care as she could on the gentleman beside her and asked him questions and then listened with attention to the answers. Listening took more work than talking; she made sure that her companion knew, from the sympathy and sharp light in her eyes, how intelligent she was, and how quietly powerful and deep.

She would suffer only when she left the company. In the carriage on the way home she would stare into the dark, knowing that what had happened in those years would not come back, that memories were no use, that there was nothing ahead except darkness. And on the bad nights, after evenings when there had been too much gaiety and brightness, she often wondered if there was a difference between her life now and the years stretching to eternity that she would spend in the grave.

She would write out a list and the writing itself would make her smile. Things to live for. Her son, Robert, would always come first, and then some of her sisters. She often thought of erasing one or two of them, and maybe one brother, but no more than one. And then Coole Park, the house in Ireland her husband had left her, or at least left their son, and to which she could return when she wished. She thought of the trees she had planted at Coole, she often dreamed of going back there to study the slow progress of things as the winter gave way to spring, or autumn came. And there were books and paintings and how light came into a high room as she pulled the shutters back in the morning. She would add these also to the list.

Below the list each time was blank paper. It was easy to fill the blank spaces with another list. A list of grim facts led by a single inescapable thought—that love had eluded her, that love would not come back, that she was alone and she would have to make the best of being alone.

On this particular evening, she crumpled the piece of paper in her hand before she stood up and made her way to the bedroom and prepared for the night. She was glad, or almost glad, that there would be no more outings that week, that no London hostess had the need for a dowager from Ireland at her table for the moment. A woman known for her listening skills and her keen intelligence had her uses, she thought, but not every night of the week.

She had liked being married; she had enjoyed being noticed as the young wife of an old man, had known the effect her quiet gaze could have on friends of her husband’s who thought she might be dull because she was not pretty. She had let them know, carefully, tactfully, keeping her voice low, that she was someone on whom nothing was lost. She had read all the latest books and she chose her words slowly when she came to discuss them. She did not want to appear clever. She made sure that she was silent without seeming shy, polite and reserved without seeming intimidated. She had no natural grace and she made up for this by having no empty opinions. She took the view that it was a mistake for a woman with her looks ever to show her teeth. In any case, she disliked laughter and preferred to smile using her eyes.

She disliked her husband only when he came to her at night in those first months; his fumbling and panting, his eager hands and his sour breath, gave her a sense that daylight and many layers of clothing and servants and large furnished rooms and chatter about politics or paintings were ways to distract people from feeling a revulsion towards each other.

There were times when she saw him in the distance or had occasion to glance at his face in repose when she viewed him as someone who had merely on a whim or a sudden need rescued her or captured her. He was too old to know her, he had seen too much and lived too long to allow anything new, such as a wife thirty-five years his junior, to enter his orbit. In the night, in those early months, as she tried to move towards him to embrace him fully, to offer herself to his dried-up spirit, she found that he was happier obsessively fondling certain parts of her body in the dark as though he were trying to find something he had mislaid. And thus as she attempted to please him, she also tried to make sure that, when he was finished, she would be able gently to turn away from him and face the dark alone as he slept and snored. She longed to wake in the morning and not have to look at his face too closely, his half-opened mouth, his stubbled cheeks, his grey whiskers, his wrinkled skin.

All over London, she thought, in the hours after midnight in rooms with curtains drawn, silence was broken by grunts and groans and sighs. It was lucky, she knew, that it was all done in secret, lucky also that no matter how much they talked of love or faithfulness or the unity of man and wife, no one would ever realize how apart people were in these hours, how deeply and singly themselves, how thoughts came that could never be shared or whispered or made known in any way. This was marriage, she thought, and it was her job to be calm about it. There were times when the grim, dull truth of it made her smile.

Nonetheless, there was in the day almost an excitement about being the wife of Sir William Gregory, of having a role to play in the world. He had been lonely, that much was clear. He had married her because he had been lonely. He longed to travel and he enjoyed the idea now that she would arrange his clothes and listen to him talk. They could enter dining rooms together as others did, rooms in which an elderly man alone would have appeared out of place, too sad somehow.

And because he knew his way around the world—he had been governor of Ceylon, among other things—he had many old friends and associates, was oddly popular and dependable and cultured and well informed and almost amusing in company. Once they arrived in Cairo, therefore, it was natural that they would stay in the same hotel as the young poet Wilfrid Scawen Blunt and his grand wife, that the two couples would dine together and find each other interesting as they discussed poetry lightly and then, as things began to change, argued politics with growing intensity and seriousness.

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt. As she lay in the bed with the light out, Lady Gregory smiled at the thought that she would not need ever to write his name down on any list. His name belonged elsewhere; it was a name she might breathe on glass or whisper to herself when things were harder than she had ever imagined that anything could become. It was a name that might have been etched on her heart if she believed in such things.

His fingers were long and beautiful; even his fingernails had a glow of health; his hair was shiny, his teeth white. And his eyes brightened as he spoke; thinking made him smile and when he smiled he exuded a sleek perfection. He was as far from her as a palace was from her house in Coole or as the heavens were from the earth. She liked looking at him as she liked looking at a Bronzino or a Titian and she was careful always to pretend that she also liked looking at his wife, Byron’s granddaughter, although she did not.

She thought of them like food, Lady Anne all watery vegetables, or sour, small potatoes, or salted fish, and the poet her husband like lamb cooked slowly for hours with garlic and thyme, or goose stuffed at Christmas. And she remembered in her childhood the watchful eye of her mother, her mother making her eat each morsel of bad winter food, leave her plate clean. Thus she forced herself to pay attention to every word Lady Anne said; she gazed at her with soft and sympathetic interest, she spoke to her with warmth and the dull intimacy that one man’s wife might have with another, hoping that soon Lady Anne would be calmed and suitably assuaged by this so she would not notice when Lady Gregory turned to the poet and ate him up with her eyes.

Blunt was on fire with passion during these evenings, composing a letter to The Times at the very dining table in support of Arabi Bey, arguing in favour of loosening the control that France and England had over Egyptian affairs, cajoling Sir William, who was of course a friend of the editor of The Times, to put pressure on the paper to publish his letter and support the cause. Sir William was quiet, watchful, gruff. It was easy for Blunt to feel that he agreed with every point Blunt was making mainly because Blunt did not notice dissent. They arranged for Lady Gregory to visit Arabi Bey’s wife and family so that she could describe to the English how refined they were, how sweet and deserving of support.

The afternoon when she returned was unusually hot. Her husband, she found, was in a deep sleep, so she did not disturb him. When she went in search of Blunt, she was told by the maid that Lady Anne had a severe headache brought on by the heat and would not be appearing for the rest of the day. Her husband the poet could be found in the garden or in the room he kept for work, where he often spent the afternoons. Lady Gregory found him in the garden; Blunt was excited to hear about her visit to Bey’s family and ready to show her a draft of a poem he had composed that morning on the matter of Egyptian freedom. She went to his study with him, not realizing until she was in the room and the door was closed that the study was in fact an extra bedroom the Blunts had taken, no different from the Gregorys’ own room except for a large desk and books and papers strewn on the floor and on the bed.

As Blunt read her the poem, he crossed the room and turned the key in the lock as though it were a normal act, what he always did as he read a new poem. He read it a second time and then left the piece of paper down on the desk and moved towards her and held her. He began to kiss her. Her only thought was that this might be the single chance she would get in her life to associate with beauty. Like a tourist in the vicinity of a great temple, she thought it would be a mistake to pass it by; it would be something she would only regret. She did not think it would last long or mean much. She also was sure that no one had seen them come down this corridor; she presumed that her husband was still sleeping; she believed that no one would find them and it would never be mentioned again between them.

Later, when she was alone and checking that there were no traces of what she had done on her skin or on her clothes, the idea that she had lain naked with the poet Blunt in a locked room on a hot afternoon and that he had, in a way that was new to her, made her cry out in ecstasy, frightened her. She had been married less than two years, time enough to know how deep her husband’s pride ran, how cold he was to those who had crossed him and how sharp and decisive he could be. They had left their child in England so they could travel to Egypt even though Sir William knew how much it pained her to be separated in this way from Robert. Were Sir William to be told that she had been visiting the poet in his private quarters, she believed he could ensure that she never saw her child again. Or he could live with her in pained silence and barely managed contempt. Or he could send her home. The corridors were full of servants, figures watching. She thought it a miracle that she had managed once to be unnoticed. She believed that she might not be so lucky a second time.

Over the weeks that followed and in London when she returned home, she discovered that Wilfrid Scawen Blunt’s talents as a poet were minor compared to his skills as an adulterer. Not only could he please her in ways that were daring and astonishing but he could ensure that they would not be discovered. The sanctity of his calling required him to have silence, solitude and quarters that his wife had no automatic right to enter. Blunt composed his poems in a locked room. He rented this room away from his main residence, choosing the place, Lady Gregory saw, not because of the ease with which it could be visited by the muses but rather for its position in a shadowy side-street close to streets where women of circumstance shopped. Thus no one would notice a respectable woman who was not his wife arriving or leaving in the mornings or the afternoons; no one would hear her cry out as she lay in bed with him; no one would ever know that each time in the hour or so she spent with him she realized that nothing would be enough for her, that she had not merely visited the temple as a tourist might, but had come to believe in and deeply need the sweet doctrine preached in its warm and towering confines.

At the beginning, she didn’t dream of being caught. Sir William was often busy in the day; he enjoyed having a long lunch with old associates, or a meeting of some sort about the National Gallery or some political or financial matter. It seemed to make him content that his wife went to the shops or to visit her friends as long as she was free in the evenings to accompany him to dinners. He was usually distant, quite distracted. It was, she thought, like being a member of the cabinet with her own tasks and responsibilities with her husband as prime minister, her husband happy that he had appointed her, and pleased, it appeared, that she carried out her tasks with the minimum of fuss.

Soon, however, when they were back in England a few months, she began to worry about exposure and to imagine with dread not his accusing her, or finding her in the act, but what would happen later. She dreamed, for example, that she had been sent home to her parents’ house in Roxborough and she was destined to spend her days wandering the corridors of the upper floor, a ghostly presence. Her mother passed her and did not speak to her. Her sisters came and went but did not seem even to see her. The servants brushed by her. Sometimes, she went downstairs, but there was no chair for her at the dining table and no place for her to sit in the drawing room. Every place had been filled by her sisters and her brothers and their guests and they were all chattering loudly and laughing and being served tea and, no matter how close she came to them, they paid her no attention.

The dream changed sometimes. She was in her own house in London or in Coole with her husband and with Robert and their servants but no one saw her, they let her come in and out of rooms, forlorn, silent, desperate. Her son appeared blind to her as he came towards her. Her husband undressed in their room at night as though she were not there and turned out the lamp in their room while she was still standing at the foot of the bed fully dressed. No one seemed to mind that she haunted the spaces they inhabited because no one noticed her. She had become, in these dreams, invisible to the world.

Despite Sir William’s absence from the house during the day and his indifference to how she spent her time as long as she did not cost him too much money, she knew that she could be unlucky. Being found out could happen because a friend or an acquaintance or, indeed, an enemy could suspect her and follow her, or Lady Anne could find a key to the room and come with urgent news for her husband or visit suddenly out of sheer curiosity. Blunt was careful and dependable, she knew, but he was also passionate and excitable. In some fit of rage, or moment where he lost his composure, he could easily, she thought, say enough to someone that they would understand he was having an affair with the young wife of Sir William Gregory. Her husband had many old friends in London. A note left at his club would be enough to cause him to have her watched and followed. The affair with Blunt, she realized, could not last. As months went by, she left it to Blunt to decide when it should end. It would be best, she thought, if he tired of her and found another. It would be less painful to be jealous of someone else than to feel that she had denied herself this deep fulfilling pleasure for no reason other than fear or caution.

Up to this she had put no real thought into what marriage meant. It was, she had vaguely thought, a contract, or even a sacrament. It was what happened. It was part of the way things were ordered. Sometimes now, however, when she saw the Blunts socially, or when she read a poem by him or heard someone mention his name, the fact that it was not known and publicly understood that she was with him hurt her profoundly, made her experience what existed between them as a kind of emptiness or absence. She knew that if her secret were known or told, it would destroy her life. But as time went by, its not being known by anyone at all made her imagine with relish and energy what it would be like to be married to Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, to enter a room with him, to leave in a carriage with him, to have her name openly linked with his. It would mean everything. Instead, the time she spent alone with him often came to seem like nothing when it was over. Memory, which was once so sharp and precious for her, was now a dark room in which she wandered longing for the light to be switched on or the curtains pulled back. She longed for the light of publicity, for her secret life to become common knowledge. It was something, she was well aware, that would not happen as long as she lived if she could help it. She would take her pleasure in darkness.

When the affair ended, she felt at times as if it had not happened. There was nothing solid or sure about it. Most women, she thought, had a close, discreet friend to whom such things could be whispered. She did not. In France, she understood, they had a way of making such things subtly known. Now she understood why. She was lonely without Blunt, but she was lonelier at the idea that the world went on as though she had not loved him. Time would pass and their actions and feelings would seem like a shadow of actions and feelings, but less than a shadow in fact, because cast by something that now had no real substance.

Thus she wrote the sonnets, using the time she now had to work on rhyme schemes and poetic forms. She wrote in secret about her secret love for him and then kept the paper on which she had written it down:

Bowing my head to kiss the very ground

On which the feet of him I love have trod,

Controlled and guided by that voice whose sound

Is dearer to me than the voice of God.

She put on paper her fear of disclosure and the shame that might come with it; she hid the pages away and found them when the house was quiet and she could read of what she had done and what it meant:

Should e’er that drear day come in which the world

Shall know the secret which so close I hold,

Should taunts and jeers at my bowed head be hurled,

And all my love and all my shame be told,

I could not, as some women used to do,

Fling jests and gold and live the scandal down.

When she asked, some months after their separation, to meet him one more time, his tone in reply was brusque, almost cold. She wondered if he thought that she was going to appeal to him to resume their affair, or remonstrate with him in some way. She enjoyed how surprised he seemed that she was merely handing him a sheaf of sonnets, making clear as soon as she gave him the pages that she had written them herself. She watched him reading them.

“What shall we do with them?” he asked when he had finished.

“You shall publish them in your next book as though they were written by you,” she said.

“But it is clear from the style that they are not.”

“Let the world believe that you changed your style for the purposes of writing them. Let your readers believe that you were writing in another voice. That will explain the awkwardness.”

“There is no awkwardness. They are very good.”

“Then publish them. They are yours.”

He agreed then to publish them under his own name in his next book, having made some minor alterations to them. They came out six weeks before Sir William died. Lady Gregory did her husband the favour in those weeks of not keeping the book by her bed but in her study; she managed also to keep these poems out of her mind as she watched over him.

As his widow, she knew who she was and what she had inherited. She had loved him in her way and sometimes missed him. She knew what words like “loved” and “missed” meant when she thought of her husband. When she thought of Blunt, on the other hand, she was unsure what anything meant except the sonnets she had written about their love affair. She read them sparingly, often needing them if she woke in the night, but keeping them away from her much of the time. It was enough for her that all over London, in the houses of people who acquired new books of poetry, these poems rested silently and mysteriously between the pages. She found solace in the idea that people would read them without knowing their source.

She rebuilt her life as a widow and took care of her son and began, after a suitable period of mourning, to go out in London again and meet people and take part in things. She often asked herself if there was someone in the room, or in the street, who had read her sonnets and been puzzled or pained by them, even for a second.

She had read Henry James as his books appeared. In fact, it was a discussion about Roderick Hudson that caused Sir William to pay attention to her first. She had read an extract from it but did not have the book. He arranged for it to be sent to her. Some time after her marriage, when she was visiting Rome with Sir William, she met James and she remembered him fondly as a man who would talk seriously to a woman, even someone as young and provincial as she was. She remembered asking him at that first meeting in Rome how he could possibly have allowed Isabel Archer to marry the odious Osmond. He told her that Isabel was bound to do something foolish and, if she had not, there would have been no story. And he had enjoyed, he had said, as a poor man himself, bestowing so much money on his heroine. Henry James was kind and witty, she had felt then, and somehow managed not to be glib or patronizing.

Since her husband died she had seen Henry James a number of times, noticing always how much of himself he held back, how the expression on his face appeared to disguise as much as it disclosed. He had always been very polite to her, and they had often discussed the fate of the orphan Paul Harvey, with whose mother they had both been friends. She was surprised one evening to see the novelist at a supper that Lady Layard had invited her to; there were diplomats present and some foreigners, and a few military men and some minor politicians. It was not Henry James’s world, and it was Lady Gregory’s world only in that an extra woman was needed, as people might need an extra carriage or an extra towel in the bathroom. It did not matter who she was as long as she arrived on time and left at an appropriate moment and did not talk too loudly or compete in any way with the hostess.

It made sense to place her beside Henry James. In the company on a night where politics would be discussed between the men and silliness between the women, neither of them mattered. She looked forward to having the novelist on her right. Once she disposed of a young Spanish diplomat on her left, she would attend to James and ask him about his work. When they were all dead, she thought, he would be the one whose name would live on, but it was perhaps important for those who were rich or powerful to spend their evenings keeping this poor thought at bay.

It was the Spaniard’s fingers she noticed, they were long and slender with beautiful rounded nails. She found herself glancing down at them as often as she could, hoping that the diplomat, whose accent was beyond her, would not spot what she was doing. She looked at his eyes and nodded as he spoke, all the time wondering if it would be rude for her to glance down again, this time for longer. Somewhere near London, Wilfrid Scawen Blunt was dining too, she thought, perhaps with his wife and some friends. She pictured him reaching for something at the table, a jug of water perhaps, and pouring it. She pictured his long slender fingers, the rounded nails, and then began to imagine his hair, how silky it was to the touch, and the fine bones on his face and his teeth and his breath.

She stopped herself now and began to concentrate hard on what the Spaniard was saying. She asked him a question that he failed to understand so she repeated it, making it simpler. When she had asked a number of other questions and listened attentively to the replies, she was relieved when she knew that her time with him was up and she could turn now to Henry James, who seemed heavier than before as though his large head were filled with oak or ivory. As they began to talk, he took her in with his grey eyes, which had a level of pure understanding in them that was almost affecting. For a split second she was tempted to tell him what had happened with Blunt, suggest that it occurred to a friend of hers while visiting Egypt, a friend married to an older man who was seduced by a friend of his, a poet. But she knew it was ridiculous, James would see through her immediately.

Yet something had stirred in her, a need that she had ruminated on in the past but kept out of her mind for some time now. She wanted to say Blunt’s name and wondered if she could find a way to ask James if he read his work or admired it. But James was busy describing the best way to see old Rome now that Rome had changed so much, and the best way to avoid Americans in Rome, Americans one did not want to see or be associated with. How odd he would think her were she to interrupt him or wait for a break in the conversation and ask him what he thought of the work of Wilfrid Scawen Blunt! It was possible he did not even read modern poetry. It would be hard, she thought, to turn the conversation around to Blunt or even find a way to mention him in passing. In any case, James had moved his arena of concern to Venice and was discussing whether it was best to lodge with friends there or find one’s own lodging and thus win greater independence.

As he pondered the relative merits of various American hostesses in Venice, going over the quality of their table, the size of their guest rooms, what they put at one’s disposal, she thought of love. James sighed and mentioned how a warm personality, especially of the American sort, had a way of cooling one’s appreciation of ancient beauty, irrespective of how grand the palazzo of which this personality was in possession, indeed irrespective of how fine or fast-moving her gondola.

When he had finished, Lady Gregory turned towards him quietly and asked him if he was tired of people telling him stories he might use in his fiction, or if he viewed such offerings as an essential element in his art. He told her in reply that he often, later when he arrived home, noted down something interesting that had been said to him, and on occasion the germ of a story had come to him from a most unlikely source, and other times, of course, from a most obvious and welcome one. He liked to imagine his characters, he said, but he also liked that they might have lived already, to some small extent perhaps, before he painted a new background for them and created a new scenario. Life, he said, life, that was the material that he used and needed. There could never be enough life. But it was only the beginning, of course, because life was thin.

There was an eminent London man, she began, a clergyman known to dine at the best tables, a man of great experience who had many friends, friends who were both surprised and delighted when this man finally married. The lady in question was known to be highly respectable. But on the day of their wedding as they crossed to France from Dover to Calais, he found a note addressed to her from a man who had clearly been her lover and now felt free, despite her new circumstances, to address her ardently and intimately.

James listened, noting every word. Lady Gregory found that she was trembling and had to control herself; she realized that she would have to speak softly and slowly. She stopped and took a sip of water, knowing that if she did not continue in a tone that was easy and nonchalant she would end by giving more away than she wished to give. The clergyman, she went on, was deeply shocked, and, since he had been married just a few hours to this woman, he decided that, when they had arrived in Paris, he would send her back home to her family, make her an outcast; she would be his wife merely in name. He would not see her again.

Instead, however, Lady Gregory went on, when they had arrived at their hotel in Paris the clergyman decided against this action. He informed his errant wife, his piece of damaged goods, that he would keep her, but he would not touch her. He would take her into his house to live, but not as his wife.

Lady Gregory tried to smile casually as she came to the end of the story. She was pleased that her listener had guessed nothing. It was a story that had elements both French and English, something that James would understand as being rather particularly part of his realm. He thanked her and said that he would note the story once he reached his study that evening and he would perhaps, he hoped, do justice to it in the future. It was always impossible to know, he added, why one small spark caused a large fire and why another was destined to extinguish itself before it had even flared.

She realized as the guests around her stood up from the table that she had said as much as she could say, which was, on reflection, hardly anything at all. She almost wished she had added more detail, had told James that the letter came from a poet perhaps, or that it contained a set of sonnets whose subject was unmistakable, or that the wife of the clergyman was more than thirty years his junior, or that he was not a clergyman at all, but a former member of parliament and someone who had once held high office. Or that the events in question had happened in Egypt and not on the way to Paris. Or that the woman had never, in fact, been caught, she had been careful and had outlived the husband to whom she had been unfaithful. That she had merely dreamed of and feared being sent home by him or kept apart, never touched.

The next time, she thought, if she found herself seated beside the novelist she would slip in one of these details. She understood perfectly why the idea excited her so much. As Henry James stood up from the table, it gave her a strange sense of satisfaction that she had lodged her secret with him, a secret over-wrapped perhaps, but at least the rudiments of its shape apparent, if not to him then to her, for whom these matters were pressing, urgent and gave meaning to her life. That she had kept the secret and told a small bit of it all at the same time made her feel light as she went to join the ladies for some conversation. It had been, on the whole, she thought, an unexpectedly interesting evening.

© 2011 Colm Tóibín

34 DVG, January 23d, 1894

Another incident—“subject”—related to me by Lady G. was that of the eminent London clergyman who on the Dover-to-Calais steamer, starting on his wedding tour, picked up on the deck a letter addressed to his wife, while she was below, and finding it to be from an old lover, and very ardent (an engagement—a rupture, a relation, in short), of which he never had been told, took the line of sending her, from Paris, straight back to her parents—without having touched her—on the ground that he had been deceived. He ended, subsequently, by taking her back into his house to live, but never lived with her as his wife. There is a drama in the various things, for her, to which that situation—that night in Paris—might have led. Her immediate surrender to some one else, etc. etc. etc.

—from The Notebooks of Henry James

Sometimes when the evening had almost ended, Lady Gregory would catch someone’s eye for a moment and that would be enough to make her remember. At those tables in the great city she knew not ever to talk about herself, or complain about anything such as the heat, or the dullness of the season, or the antics of an actress; she knew not to babble about banalities, or laugh at things that were not very funny. She focused instead with as much force and care as she could on the gentleman beside her and asked him questions and then listened with attention to the answers. Listening took more work than talking; she made sure that her companion knew, from the sympathy and sharp light in her eyes, how intelligent she was, and how quietly powerful and deep.

She would suffer only when she left the company. In the carriage on the way home she would stare into the dark, knowing that what had happened in those years would not come back, that memories were no use, that there was nothing ahead except darkness. And on the bad nights, after evenings when there had been too much gaiety and brightness, she often wondered if there was a difference between her life now and the years stretching to eternity that she would spend in the grave.

She would write out a list and the writing itself would make her smile. Things to live for. Her son, Robert, would always come first, and then some of her sisters. She often thought of erasing one or two of them, and maybe one brother, but no more than one. And then Coole Park, the house in Ireland her husband had left her, or at least left their son, and to which she could return when she wished. She thought of the trees she had planted at Coole, she often dreamed of going back there to study the slow progress of things as the winter gave way to spring, or autumn came. And there were books and paintings and how light came into a high room as she pulled the shutters back in the morning. She would add these also to the list.

Below the list each time was blank paper. It was easy to fill the blank spaces with another list. A list of grim facts led by a single inescapable thought—that love had eluded her, that love would not come back, that she was alone and she would have to make the best of being alone.

On this particular evening, she crumpled the piece of paper in her hand before she stood up and made her way to the bedroom and prepared for the night. She was glad, or almost glad, that there would be no more outings that week, that no London hostess had the need for a dowager from Ireland at her table for the moment. A woman known for her listening skills and her keen intelligence had her uses, she thought, but not every night of the week.

She had liked being married; she had enjoyed being noticed as the young wife of an old man, had known the effect her quiet gaze could have on friends of her husband’s who thought she might be dull because she was not pretty. She had let them know, carefully, tactfully, keeping her voice low, that she was someone on whom nothing was lost. She had read all the latest books and she chose her words slowly when she came to discuss them. She did not want to appear clever. She made sure that she was silent without seeming shy, polite and reserved without seeming intimidated. She had no natural grace and she made up for this by having no empty opinions. She took the view that it was a mistake for a woman with her looks ever to show her teeth. In any case, she disliked laughter and preferred to smile using her eyes.

She disliked her husband only when he came to her at night in those first months; his fumbling and panting, his eager hands and his sour breath, gave her a sense that daylight and many layers of clothing and servants and large furnished rooms and chatter about politics or paintings were ways to distract people from feeling a revulsion towards each other.

There were times when she saw him in the distance or had occasion to glance at his face in repose when she viewed him as someone who had merely on a whim or a sudden need rescued her or captured her. He was too old to know her, he had seen too much and lived too long to allow anything new, such as a wife thirty-five years his junior, to enter his orbit. In the night, in those early months, as she tried to move towards him to embrace him fully, to offer herself to his dried-up spirit, she found that he was happier obsessively fondling certain parts of her body in the dark as though he were trying to find something he had mislaid. And thus as she attempted to please him, she also tried to make sure that, when he was finished, she would be able gently to turn away from him and face the dark alone as he slept and snored. She longed to wake in the morning and not have to look at his face too closely, his half-opened mouth, his stubbled cheeks, his grey whiskers, his wrinkled skin.

All over London, she thought, in the hours after midnight in rooms with curtains drawn, silence was broken by grunts and groans and sighs. It was lucky, she knew, that it was all done in secret, lucky also that no matter how much they talked of love or faithfulness or the unity of man and wife, no one would ever realize how apart people were in these hours, how deeply and singly themselves, how thoughts came that could never be shared or whispered or made known in any way. This was marriage, she thought, and it was her job to be calm about it. There were times when the grim, dull truth of it made her smile.

Nonetheless, there was in the day almost an excitement about being the wife of Sir William Gregory, of having a role to play in the world. He had been lonely, that much was clear. He had married her because he had been lonely. He longed to travel and he enjoyed the idea now that she would arrange his clothes and listen to him talk. They could enter dining rooms together as others did, rooms in which an elderly man alone would have appeared out of place, too sad somehow.

And because he knew his way around the world—he had been governor of Ceylon, among other things—he had many old friends and associates, was oddly popular and dependable and cultured and well informed and almost amusing in company. Once they arrived in Cairo, therefore, it was natural that they would stay in the same hotel as the young poet Wilfrid Scawen Blunt and his grand wife, that the two couples would dine together and find each other interesting as they discussed poetry lightly and then, as things began to change, argued politics with growing intensity and seriousness.

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt. As she lay in the bed with the light out, Lady Gregory smiled at the thought that she would not need ever to write his name down on any list. His name belonged elsewhere; it was a name she might breathe on glass or whisper to herself when things were harder than she had ever imagined that anything could become. It was a name that might have been etched on her heart if she believed in such things.

His fingers were long and beautiful; even his fingernails had a glow of health; his hair was shiny, his teeth white. And his eyes brightened as he spoke; thinking made him smile and when he smiled he exuded a sleek perfection. He was as far from her as a palace was from her house in Coole or as the heavens were from the earth. She liked looking at him as she liked looking at a Bronzino or a Titian and she was careful always to pretend that she also liked looking at his wife, Byron’s granddaughter, although she did not.

She thought of them like food, Lady Anne all watery vegetables, or sour, small potatoes, or salted fish, and the poet her husband like lamb cooked slowly for hours with garlic and thyme, or goose stuffed at Christmas. And she remembered in her childhood the watchful eye of her mother, her mother making her eat each morsel of bad winter food, leave her plate clean. Thus she forced herself to pay attention to every word Lady Anne said; she gazed at her with soft and sympathetic interest, she spoke to her with warmth and the dull intimacy that one man’s wife might have with another, hoping that soon Lady Anne would be calmed and suitably assuaged by this so she would not notice when Lady Gregory turned to the poet and ate him up with her eyes.

Blunt was on fire with passion during these evenings, composing a letter to The Times at the very dining table in support of Arabi Bey, arguing in favour of loosening the control that France and England had over Egyptian affairs, cajoling Sir William, who was of course a friend of the editor of The Times, to put pressure on the paper to publish his letter and support the cause. Sir William was quiet, watchful, gruff. It was easy for Blunt to feel that he agreed with every point Blunt was making mainly because Blunt did not notice dissent. They arranged for Lady Gregory to visit Arabi Bey’s wife and family so that she could describe to the English how refined they were, how sweet and deserving of support.

The afternoon when she returned was unusually hot. Her husband, she found, was in a deep sleep, so she did not disturb him. When she went in search of Blunt, she was told by the maid that Lady Anne had a severe headache brought on by the heat and would not be appearing for the rest of the day. Her husband the poet could be found in the garden or in the room he kept for work, where he often spent the afternoons. Lady Gregory found him in the garden; Blunt was excited to hear about her visit to Bey’s family and ready to show her a draft of a poem he had composed that morning on the matter of Egyptian freedom. She went to his study with him, not realizing until she was in the room and the door was closed that the study was in fact an extra bedroom the Blunts had taken, no different from the Gregorys’ own room except for a large desk and books and papers strewn on the floor and on the bed.

As Blunt read her the poem, he crossed the room and turned the key in the lock as though it were a normal act, what he always did as he read a new poem. He read it a second time and then left the piece of paper down on the desk and moved towards her and held her. He began to kiss her. Her only thought was that this might be the single chance she would get in her life to associate with beauty. Like a tourist in the vicinity of a great temple, she thought it would be a mistake to pass it by; it would be something she would only regret. She did not think it would last long or mean much. She also was sure that no one had seen them come down this corridor; she presumed that her husband was still sleeping; she believed that no one would find them and it would never be mentioned again between them.

Later, when she was alone and checking that there were no traces of what she had done on her skin or on her clothes, the idea that she had lain naked with the poet Blunt in a locked room on a hot afternoon and that he had, in a way that was new to her, made her cry out in ecstasy, frightened her. She had been married less than two years, time enough to know how deep her husband’s pride ran, how cold he was to those who had crossed him and how sharp and decisive he could be. They had left their child in England so they could travel to Egypt even though Sir William knew how much it pained her to be separated in this way from Robert. Were Sir William to be told that she had been visiting the poet in his private quarters, she believed he could ensure that she never saw her child again. Or he could live with her in pained silence and barely managed contempt. Or he could send her home. The corridors were full of servants, figures watching. She thought it a miracle that she had managed once to be unnoticed. She believed that she might not be so lucky a second time.

Over the weeks that followed and in London when she returned home, she discovered that Wilfrid Scawen Blunt’s talents as a poet were minor compared to his skills as an adulterer. Not only could he please her in ways that were daring and astonishing but he could ensure that they would not be discovered. The sanctity of his calling required him to have silence, solitude and quarters that his wife had no automatic right to enter. Blunt composed his poems in a locked room. He rented this room away from his main residence, choosing the place, Lady Gregory saw, not because of the ease with which it could be visited by the muses but rather for its position in a shadowy side-street close to streets where women of circumstance shopped. Thus no one would notice a respectable woman who was not his wife arriving or leaving in the mornings or the afternoons; no one would hear her cry out as she lay in bed with him; no one would ever know that each time in the hour or so she spent with him she realized that nothing would be enough for her, that she had not merely visited the temple as a tourist might, but had come to believe in and deeply need the sweet doctrine preached in its warm and towering confines.

At the beginning, she didn’t dream of being caught. Sir William was often busy in the day; he enjoyed having a long lunch with old associates, or a meeting of some sort about the National Gallery or some political or financial matter. It seemed to make him content that his wife went to the shops or to visit her friends as long as she was free in the evenings to accompany him to dinners. He was usually distant, quite distracted. It was, she thought, like being a member of the cabinet with her own tasks and responsibilities with her husband as prime minister, her husband happy that he had appointed her, and pleased, it appeared, that she carried out her tasks with the minimum of fuss.

Soon, however, when they were back in England a few months, she began to worry about exposure and to imagine with dread not his accusing her, or finding her in the act, but what would happen later. She dreamed, for example, that she had been sent home to her parents’ house in Roxborough and she was destined to spend her days wandering the corridors of the upper floor, a ghostly presence. Her mother passed her and did not speak to her. Her sisters came and went but did not seem even to see her. The servants brushed by her. Sometimes, she went downstairs, but there was no chair for her at the dining table and no place for her to sit in the drawing room. Every place had been filled by her sisters and her brothers and their guests and they were all chattering loudly and laughing and being served tea and, no matter how close she came to them, they paid her no attention.

The dream changed sometimes. She was in her own house in London or in Coole with her husband and with Robert and their servants but no one saw her, they let her come in and out of rooms, forlorn, silent, desperate. Her son appeared blind to her as he came towards her. Her husband undressed in their room at night as though she were not there and turned out the lamp in their room while she was still standing at the foot of the bed fully dressed. No one seemed to mind that she haunted the spaces they inhabited because no one noticed her. She had become, in these dreams, invisible to the world.

Despite Sir William’s absence from the house during the day and his indifference to how she spent her time as long as she did not cost him too much money, she knew that she could be unlucky. Being found out could happen because a friend or an acquaintance or, indeed, an enemy could suspect her and follow her, or Lady Anne could find a key to the room and come with urgent news for her husband or visit suddenly out of sheer curiosity. Blunt was careful and dependable, she knew, but he was also passionate and excitable. In some fit of rage, or moment where he lost his composure, he could easily, she thought, say enough to someone that they would understand he was having an affair with the young wife of Sir William Gregory. Her husband had many old friends in London. A note left at his club would be enough to cause him to have her watched and followed. The affair with Blunt, she realized, could not last. As months went by, she left it to Blunt to decide when it should end. It would be best, she thought, if he tired of her and found another. It would be less painful to be jealous of someone else than to feel that she had denied herself this deep fulfilling pleasure for no reason other than fear or caution.

Up to this she had put no real thought into what marriage meant. It was, she had vaguely thought, a contract, or even a sacrament. It was what happened. It was part of the way things were ordered. Sometimes now, however, when she saw the Blunts socially, or when she read a poem by him or heard someone mention his name, the fact that it was not known and publicly understood that she was with him hurt her profoundly, made her experience what existed between them as a kind of emptiness or absence. She knew that if her secret were known or told, it would destroy her life. But as time went by, its not being known by anyone at all made her imagine with relish and energy what it would be like to be married to Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, to enter a room with him, to leave in a carriage with him, to have her name openly linked with his. It would mean everything. Instead, the time she spent alone with him often came to seem like nothing when it was over. Memory, which was once so sharp and precious for her, was now a dark room in which she wandered longing for the light to be switched on or the curtains pulled back. She longed for the light of publicity, for her secret life to become common knowledge. It was something, she was well aware, that would not happen as long as she lived if she could help it. She would take her pleasure in darkness.

When the affair ended, she felt at times as if it had not happened. There was nothing solid or sure about it. Most women, she thought, had a close, discreet friend to whom such things could be whispered. She did not. In France, she understood, they had a way of making such things subtly known. Now she understood why. She was lonely without Blunt, but she was lonelier at the idea that the world went on as though she had not loved him. Time would pass and their actions and feelings would seem like a shadow of actions and feelings, but less than a shadow in fact, because cast by something that now had no real substance.

Thus she wrote the sonnets, using the time she now had to work on rhyme schemes and poetic forms. She wrote in secret about her secret love for him and then kept the paper on which she had written it down:

Bowing my head to kiss the very ground

On which the feet of him I love have trod,

Controlled and guided by that voice whose sound

Is dearer to me than the voice of God.

She put on paper her fear of disclosure and the shame that might come with it; she hid the pages away and found them when the house was quiet and she could read of what she had done and what it meant:

Should e’er that drear day come in which the world

Shall know the secret which so close I hold,

Should taunts and jeers at my bowed head be hurled,

And all my love and all my shame be told,

I could not, as some women used to do,

Fling jests and gold and live the scandal down.

When she asked, some months after their separation, to meet him one more time, his tone in reply was brusque, almost cold. She wondered if he thought that she was going to appeal to him to resume their affair, or remonstrate with him in some way. She enjoyed how surprised he seemed that she was merely handing him a sheaf of sonnets, making clear as soon as she gave him the pages that she had written them herself. She watched him reading them.

“What shall we do with them?” he asked when he had finished.

“You shall publish them in your next book as though they were written by you,” she said.

“But it is clear from the style that they are not.”

“Let the world believe that you changed your style for the purposes of writing them. Let your readers believe that you were writing in another voice. That will explain the awkwardness.”

“There is no awkwardness. They are very good.”

“Then publish them. They are yours.”

He agreed then to publish them under his own name in his next book, having made some minor alterations to them. They came out six weeks before Sir William died. Lady Gregory did her husband the favour in those weeks of not keeping the book by her bed but in her study; she managed also to keep these poems out of her mind as she watched over him.

As his widow, she knew who she was and what she had inherited. She had loved him in her way and sometimes missed him. She knew what words like “loved” and “missed” meant when she thought of her husband. When she thought of Blunt, on the other hand, she was unsure what anything meant except the sonnets she had written about their love affair. She read them sparingly, often needing them if she woke in the night, but keeping them away from her much of the time. It was enough for her that all over London, in the houses of people who acquired new books of poetry, these poems rested silently and mysteriously between the pages. She found solace in the idea that people would read them without knowing their source.

She rebuilt her life as a widow and took care of her son and began, after a suitable period of mourning, to go out in London again and meet people and take part in things. She often asked herself if there was someone in the room, or in the street, who had read her sonnets and been puzzled or pained by them, even for a second.

She had read Henry James as his books appeared. In fact, it was a discussion about Roderick Hudson that caused Sir William to pay attention to her first. She had read an extract from it but did not have the book. He arranged for it to be sent to her. Some time after her marriage, when she was visiting Rome with Sir William, she met James and she remembered him fondly as a man who would talk seriously to a woman, even someone as young and provincial as she was. She remembered asking him at that first meeting in Rome how he could possibly have allowed Isabel Archer to marry the odious Osmond. He told her that Isabel was bound to do something foolish and, if she had not, there would have been no story. And he had enjoyed, he had said, as a poor man himself, bestowing so much money on his heroine. Henry James was kind and witty, she had felt then, and somehow managed not to be glib or patronizing.

Since her husband died she had seen Henry James a number of times, noticing always how much of himself he held back, how the expression on his face appeared to disguise as much as it disclosed. He had always been very polite to her, and they had often discussed the fate of the orphan Paul Harvey, with whose mother they had both been friends. She was surprised one evening to see the novelist at a supper that Lady Layard had invited her to; there were diplomats present and some foreigners, and a few military men and some minor politicians. It was not Henry James’s world, and it was Lady Gregory’s world only in that an extra woman was needed, as people might need an extra carriage or an extra towel in the bathroom. It did not matter who she was as long as she arrived on time and left at an appropriate moment and did not talk too loudly or compete in any way with the hostess.

It made sense to place her beside Henry James. In the company on a night where politics would be discussed between the men and silliness between the women, neither of them mattered. She looked forward to having the novelist on her right. Once she disposed of a young Spanish diplomat on her left, she would attend to James and ask him about his work. When they were all dead, she thought, he would be the one whose name would live on, but it was perhaps important for those who were rich or powerful to spend their evenings keeping this poor thought at bay.

It was the Spaniard’s fingers she noticed, they were long and slender with beautiful rounded nails. She found herself glancing down at them as often as she could, hoping that the diplomat, whose accent was beyond her, would not spot what she was doing. She looked at his eyes and nodded as he spoke, all the time wondering if it would be rude for her to glance down again, this time for longer. Somewhere near London, Wilfrid Scawen Blunt was dining too, she thought, perhaps with his wife and some friends. She pictured him reaching for something at the table, a jug of water perhaps, and pouring it. She pictured his long slender fingers, the rounded nails, and then began to imagine his hair, how silky it was to the touch, and the fine bones on his face and his teeth and his breath.

She stopped herself now and began to concentrate hard on what the Spaniard was saying. She asked him a question that he failed to understand so she repeated it, making it simpler. When she had asked a number of other questions and listened attentively to the replies, she was relieved when she knew that her time with him was up and she could turn now to Henry James, who seemed heavier than before as though his large head were filled with oak or ivory. As they began to talk, he took her in with his grey eyes, which had a level of pure understanding in them that was almost affecting. For a split second she was tempted to tell him what had happened with Blunt, suggest that it occurred to a friend of hers while visiting Egypt, a friend married to an older man who was seduced by a friend of his, a poet. But she knew it was ridiculous, James would see through her immediately.

Yet something had stirred in her, a need that she had ruminated on in the past but kept out of her mind for some time now. She wanted to say Blunt’s name and wondered if she could find a way to ask James if he read his work or admired it. But James was busy describing the best way to see old Rome now that Rome had changed so much, and the best way to avoid Americans in Rome, Americans one did not want to see or be associated with. How odd he would think her were she to interrupt him or wait for a break in the conversation and ask him what he thought of the work of Wilfrid Scawen Blunt! It was possible he did not even read modern poetry. It would be hard, she thought, to turn the conversation around to Blunt or even find a way to mention him in passing. In any case, James had moved his arena of concern to Venice and was discussing whether it was best to lodge with friends there or find one’s own lodging and thus win greater independence.

As he pondered the relative merits of various American hostesses in Venice, going over the quality of their table, the size of their guest rooms, what they put at one’s disposal, she thought of love. James sighed and mentioned how a warm personality, especially of the American sort, had a way of cooling one’s appreciation of ancient beauty, irrespective of how grand the palazzo of which this personality was in possession, indeed irrespective of how fine or fast-moving her gondola.

When he had finished, Lady Gregory turned towards him quietly and asked him if he was tired of people telling him stories he might use in his fiction, or if he viewed such offerings as an essential element in his art. He told her in reply that he often, later when he arrived home, noted down something interesting that had been said to him, and on occasion the germ of a story had come to him from a most unlikely source, and other times, of course, from a most obvious and welcome one. He liked to imagine his characters, he said, but he also liked that they might have lived already, to some small extent perhaps, before he painted a new background for them and created a new scenario. Life, he said, life, that was the material that he used and needed. There could never be enough life. But it was only the beginning, of course, because life was thin.

There was an eminent London man, she began, a clergyman known to dine at the best tables, a man of great experience who had many friends, friends who were both surprised and delighted when this man finally married. The lady in question was known to be highly respectable. But on the day of their wedding as they crossed to France from Dover to Calais, he found a note addressed to her from a man who had clearly been her lover and now felt free, despite her new circumstances, to address her ardently and intimately.

James listened, noting every word. Lady Gregory found that she was trembling and had to control herself; she realized that she would have to speak softly and slowly. She stopped and took a sip of water, knowing that if she did not continue in a tone that was easy and nonchalant she would end by giving more away than she wished to give. The clergyman, she went on, was deeply shocked, and, since he had been married just a few hours to this woman, he decided that, when they had arrived in Paris, he would send her back home to her family, make her an outcast; she would be his wife merely in name. He would not see her again.

Instead, however, Lady Gregory went on, when they had arrived at their hotel in Paris the clergyman decided against this action. He informed his errant wife, his piece of damaged goods, that he would keep her, but he would not touch her. He would take her into his house to live, but not as his wife.

Lady Gregory tried to smile casually as she came to the end of the story. She was pleased that her listener had guessed nothing. It was a story that had elements both French and English, something that James would understand as being rather particularly part of his realm. He thanked her and said that he would note the story once he reached his study that evening and he would perhaps, he hoped, do justice to it in the future. It was always impossible to know, he added, why one small spark caused a large fire and why another was destined to extinguish itself before it had even flared.

She realized as the guests around her stood up from the table that she had said as much as she could say, which was, on reflection, hardly anything at all. She almost wished she had added more detail, had told James that the letter came from a poet perhaps, or that it contained a set of sonnets whose subject was unmistakable, or that the wife of the clergyman was more than thirty years his junior, or that he was not a clergyman at all, but a former member of parliament and someone who had once held high office. Or that the events in question had happened in Egypt and not on the way to Paris. Or that the woman had never, in fact, been caught, she had been careful and had outlived the husband to whom she had been unfaithful. That she had merely dreamed of and feared being sent home by him or kept apart, never touched.

The next time, she thought, if she found herself seated beside the novelist she would slip in one of these details. She understood perfectly why the idea excited her so much. As Henry James stood up from the table, it gave her a strange sense of satisfaction that she had lodged her secret with him, a secret over-wrapped perhaps, but at least the rudiments of its shape apparent, if not to him then to her, for whom these matters were pressing, urgent and gave meaning to her life. That she had kept the secret and told a small bit of it all at the same time made her feel light as she went to join the ladies for some conversation. It had been, on the whole, she thought, an unexpectedly interesting evening.

© 2011 Colm Tóibín