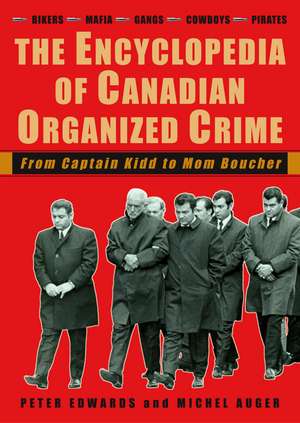

The Encyclopedia of Canadian Organized Crime: From Captain Kidd to Mom Boucher

Autor Peter Edwards, Michel Augeren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2004

Respected crime reporters Peter Edwards and Michel Auger have pooled their research and expertise to create The Encyclopedia of Canadian Organized Crime. Sometimes grim, sometimes amusing, and always entertaining, this book is filled with 300 entries and more than 150 illustrations, covering centuries of organized crime. From pirates such as “Black Bart,” who sheltered in isolated Newfoundland coves to strike at the shipping lanes between Europe and the North American colonies, all the way to the most recent influx of Russianmobsters, who arrived after the end of the Cold War in 1989 and are now honing their sophisticated technological skills on the Western public, Edwards and Auger enumerate the personalities and the crimes that have kept Canadian law enforcement busy. Here too are the Sicilian and Calabrian gangs, the American and Colombian drug connections, the bikers whose internal struggles have left innocent bystanders dead (and who tried to murder Auger), as well as many unexpected figures, such as the Sundance Kid, who spent years in Canada.

Arranged in alphabetical entries for easy browsing, and illustratedthroughout with photographs and drawings, this is a book that will both entertain and inform.

Preț: 156.28 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 234

Preț estimativ în valută:

29.91€ • 31.18$ • 24.86£

29.91€ • 31.18$ • 24.86£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780771030444

ISBN-10: 0771030444

Pagini: 272

Ilustrații: ILLUSTRATIONS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 178 x 248 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.52 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

ISBN-10: 0771030444

Pagini: 272

Ilustrații: ILLUSTRATIONS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 178 x 248 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.52 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Notă biografică

Peter Edwards, a reporter for the Toronto Star, is the author of One Dead Indian and A Mother’s Story: The Fight to Free My Son David (with Joyce Milgaard), which was shortlisted for an Arthur Ellis Award.

Michel Auger is a reporter with Le Journal de Montréal. In 2000, he was shot in the back, probably by bikers, and wrote about it in The Biker Who Shot Me: Recollections of a Crime Reporter.

Michel Auger is a reporter with Le Journal de Montréal. In 2000, he was shot in the back, probably by bikers, and wrote about it in The Biker Who Shot Me: Recollections of a Crime Reporter.

Extras

Organized crime is a slippery subject, involving slippery people, and evades an exact definition. In drawing up this list of organized criminals and groups, we have been strongly influenced by new anti-gang laws, which define a criminal organization as a group of three or more people whose main activities include committing crimes for some benefit. We realize that sometimes there’s a fine line between terrorism and organized crime, as with the attacks by the Hells Angels on the justice system in Quebec in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Other times, criminals are clearly habitual offenders, but it’s a generous stretch to call them organized. For the purposes of this book, we have largely focused on criminal activities in which profit was the main motive, as opposed to passion, perversion, mental illness, or politics. We were also interested in criminal activity that was ongoing and which involved planning. Finally, we looked for some specific code of conduct: one existed on the pirate ships of Peter Easton in the early seventeenth century and they can still be found today amongst modern-day biker gangs and Mafia groups.

Also, it should be clear that this is a book about crime and criminals, not ethnic groups. There’s diversity in crime as well as in mainstream Canadian life, and organized criminals make up just a minuscule fraction of any ethnic group mentioned here. For instance, crime analysts have estimated that 0.02 per cent of the Italian-heritage community is involved in Mafia activity in Canada.

We often wondered, Why do some criminals enjoy longevity, while others don’t? One common thread shared by the successful organized criminals described in these pages is a vital link to transportation routes. To be effective for any length of time, groups have to be able to move goods and people, whether they’re taking illegal drugs to market or moving themselves — speedily — out of harm’s way. Such access to transportation routes was standard amongst the seventeenth-century pirates of the Atlantic coast, the coureurs de bois of pre-Confederation, the bootlegging gangs that followed crews building the Canadian Pacific Railway, criminals like the Sundance Kid on the Outlaw Trail of southern Saskatchewan at the turn of the twentieth century, the bootleggers of Prohibition, and, today, the cocaine cartels and the Hells Angels, with their acute interest in the shipping ports of Vancouver, Montreal, and Halifax.

But perhaps the most important central thread connecting the groups described in these pages is control of officials — either through corruption or intimidation. They all need to compromise officials in ostensibly legitimate jobs in order to function for any length of time. This was as true in the days of the early seventeenth-century pirates as it is today. Harry Longabaugh (The Sundance Kid) and his associates benefited from the assistance of a corrupt former North-West Mounted Police officer, who helped them hide out in the gullies around Big Beaver in southern Saskatchewan. Montreal mobsters Vincenzo “Vic the Egg” Cotroni and Willie Obront were called “The Untouchables” by crusading police officer Pacifique “Pax” Plante because of their excellent political connections. Maurice “Mom” Boucher of the Hells Angels took a far more brutal route to attain the same ends, using murder and the threat of violence to try to intimidate members of the judicial, legislative, and journalistic communities.

In a sense, the major criminals described in these pages weren’t really “outlaws” at all, since they needed a strong, ongoing connection to the legitimate world to survive, much like a leech or a parasite is dependent upon its host. Many tried to use their loot to buy respectability and a place in the legitimate world, and more than a few succeeded. Eric Cobham, a particularly vicious sea dog who prowled Canada’s Atlantic coast in the seventeenth century, purchased a title in the French gentry and became a magistrate, while fellow pirates Peter “The Pirate Admiral” Easton and Henry Mainwaring each bought pardons, retiring in luxury with the titles of marquis and knight, respectively. While Captain Kidd was immeasurably less violent, and didn’t even consider himself a criminal, his life ended on the gallows, as he had fallen from grace in political circles.

Organized crime is nothing new in Canada, and it was thriving 250 years before Confederation. It fuelled the adventures of fur-trading pioneers like Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Sieur des Groseilliers, known to Canadian schoolchildren as “Radishes and Gooseberries,” and the much-romanticized coureurs de bois, who operated outside the law in New France for a century before their fur-trading operation was finally made legal in 1700. The money they generated supported legitimate businesses and, in effect, propped up the economy of the early colony.

Organized crime is also present when you look at such Canadian institutions as the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Canadian Pacific Railway. Indeed, bootleggers seized control of the entire town of Michipicoten, a former Hudson’s Bay Company post on the north shore of Lake Superior in the fall of 1884, using it as their headquarters for selling booze to men working on the railway. Such activities brought to mind the saying “Steal a dollar and they throw you in jail. Steal a million and they make you king.”

Even the Hells Angels biker gang isn’t comfortable with a totally outlaw image. They obviously crave a certain legitimacy, which explains the controversial public handshake between a biker and former Toronto mayor Mel Lastman in January 2002; Maurice “Mom” Boucher posing for a photo with an unwitting Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa; or a group of Angels posing for photos with Montreal Canadiens’ goalie Jose Theodore or with Pat Burns, back when Burns coached the Toronto Maple Leafs of the National Hockey League. At times, the Angels’ actions look like a sad effort to push themselves into “respectable” society.

While we’ve drawn up a fairly long list in this overview of names in Canadian organized crime, we don’t pretend it’s complete. Some readers may wonder how Woody the Biker Lion or Pearl Hart made the list and others didn’t. We admit that a few entries appear here more for quirkiness than for their organizational skills. In general, however, we were biased toward highly structured groups, which explains why there’s more on the Hells Angels and the Mafia than the more loosely-knit Jamaican posses and Vietnamese street gangs. Barring a sudden change in human nature, there will undoubtedly be plenty more additions for future editions.

**********

The Sundance Kid: Alberta Ranch Hand — His real name was Harry Alonzo Longabaugh and he also answered to Harry Place and Frank Boyd, but he’s best known as the character played by Robert Redford in the 1969 movie Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

What’s not so well known are his Canadian roots, and that he often hid out in southern Saskatchewan and lived in Alberta from 1890 to 1892, when he was in his early to mid-twenties. Longabaugh didn’t advertise his nickname — The Sundance Kid — and certainly no one asked about it when he showed up to work as a cowboy for the North-West Cattle Company — known as the “Bar U” — west of High River, Alberta.

He got the nickname when, as a youth, he served an eighteen-month jail term in Sundance, Wyoming, for stealing a horse, a saddle, and a gun from a ranch worker in Crook County, Wyoming, when he was either sixteen or seventeen years old. Upon his release from jail on February 8, 1889, the Sundance Gazette noted that, “The term of ‘kid’ Longabaugh has expired.” From then on, he was known as the Sundance Kid.

Longabaugh returned to Colorado, where he had lived with a distant cousin, and joined Robert Leroy Parker (a.k.a. Butch Cassidy), Tom McCarty, and Matt Warner in holding up the San Miguel Valley Bank in Telluride on June 24, 1889. After that, he needed a new safe haven, and fled north to Canada in time for the 1890 cattle season.

There he looked up an old friend from Wyoming, Cyril Everett “Ebb” Johnson, who lived in the Cochrane, Alberta, area. They had worked together earlier in Wyoming at the Power River Ranch, which expanded into Canada in 1886, leasing land on Mosquito Creek, near where the town of Nanton is today. It had the brand of “76” and that was its local nickname.

Johnson was foreman of the “Bar U,” which had 10,410 cattle and 832 horses in 1890. Sundance quickly proved to be a valuable employee, as well as a popular one. Fred Ings of the nearby Midway Ranch noted that “a thoroughly likeable fellow was Harry, a general favorite with everyone, a splendid rider and a top notch cow hand.” Ings also said that the Kid was law-abiding and “no one could have been better behaved or more decent.”

Ings had reason to say nice things about him, since he believed the Sundance Kid saved his life during a fall roundup. “One . . . night on Mosquito Creek was one of the worst times I ever went through. A blizzard was coming from the north with blinding snow. I was given the ten o’clock shift, and with me was Harry Longdebough [sic], a good-looking young American cow puncher who feared neither man nor devil.”

The herd was large, made up mostly of heavy beef cattle. Sundance drove ahead to direct them while Ings stayed at the back to hold them together.

Ings continued: “I was riding a sure-footed, thick-set, little grey horse, but I had a dozen falls that stormy night. In spite of being warmly dressed, we found it desperately cold and in the thickly falling snow lost all sense of locality.”

The Sundance Kid rode back to find Ings lost at the rear of the herd, and helped guide him back to camp, likely saving his life.

Rancher Bert Sheppard also had a high opinion of Sundance, describing him as “a good rider, roper and all-round top hand.” Most of his acquaintances seemed to know he had been in trouble in the United States, but he was fully accepted because of his ability and his friendly attitude.

He also worked for the McHugh Brothers at the H2 Ranch, on the Bow River near Carseland, Alberta, where they had a contract to supply beef to the nearby Blackfoot reserve. Also while in Alberta, he was believed to have worked breaking horses for contractors who were laying the railroad from Calgary to Fort MacLeod.

He appeared in the spring 1891 Dominion Census, District No. 197. The Bar U Ranch was enumerated on April 6, 1891, with eighteen residents, including “Henry Longabough [sic], age 25, birthplace U.S.A., occupation horse breaker.”

Not everyone liked him. A cowboy at the Bar U, Herbert Millar, claimed that he saw a small hacksaw hidden between Sundance’s saddle and his horse blanket. This may be tied to his arrest by the North-West Mounted Police for “cruelty to animals” on August 7, 1891. Sundance hired a lawyer, J.A. Bangs, and the charges were immediately dismissed the same day by Super intendent J.H. McIllree and Inspector A.R. Cuthbert. No explanation was given for their immediate dismissal. He was kept on at Bar U, suggesting the ranch’s owners did not believe the charges of animal cruelty had any factual foundation.

On November 18, 1891, Sundance signed as the witness and best man at the wedding of his friend Ebb Johnson and his bride, Mary Eleanor Bigland, at The Grange, a Calgary-area ranch owned by her uncle, with Rev. J.C. Herdman of Knox Presbyterian Church in Calgary presiding.

Some time after the wedding, Sundance left the Bar U, perhaps because Millar, who had pushed the cruelty to animals charges, had become the foreman there. He went into partnership with Frank Hamilton at the Grand Central Hotel saloon on Atlantic Avenue in Calgary, across the street from the railway depot. There are unverified reports that Butch Cassidy visited Calgary during that time, and that he even may have worked at a Calgary livery stable.

The partnership between Sundance and Hamilton didn’t last long, and ended in gunplay. Hamilton had a reputation for taking in partners and then choosing to fight them rather than hand over their share of the profits.

Sundance wouldn’t be intimidated. Author Vicky Kelly said that he vaulted over the bar and “before his feet hit the floor his gun was jammed in his partner’s middle.” The debt was paid, but the partnership was over, and early in 1892, Sundance returned to the United States.

There, he soon hooked up with rustlers Dutch Henry Ieach and Frank Jones, and together they ran stolen horses from the Culbertson and Plentywood area of Montana across into the Big Muddy Badlands of southern Saskatchewan, near the community of Big Beaver. It was the first stop on the Outlaw Trail, a string of safe havens stretching down to Mexico. This one was particularly safe, because American authorities could not cross the border into Canada.

Sundance joined a band of about ten outlaws called the Wild Bunch, who thrived from 1896 through 1901, and whose ranks included Robert Leroy Parker (Butch Cassidy). Sometimes the gang included Bill Curry, an outlaw originally from Prince Edward Island.

The Wild Bunch robbed banks and slow-moving, cash-carrying trains, but perhaps their proudest moment came on September 19, 1900, after they held up the First National Bank in Winnemucca, Nevada. They made off with $30,000, and legend has it they headed for Fort Worth, Texas, where they posed for a group photograph, then mailed it to the bank, with a note of thanks for the “withdrawal.”

Often, in times of stress, Sundance retreated to the Big Beaver area of southern Saskatchewan. He had fled there after the November 29, 1892, robbery of a Great Northern Railway train at Malta, Montana, and a police report from the time speculated he may have also gone to Calgary to visit Ebb Johnson.

However, times changed. Trains got faster and private security companies got more efficient, and ultimately Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid ended up in Bolivia. A 1909 report said that Sundance and Butch were killed there by a posse after a payroll robbery. News of his robberies filtered up to the Calgary area, where he had many friends. Fred Ings wrote, “We all felt sorry when he left and got in bad again across the line.”

Another story, promoted by Cassidy’s sister, was that the Sundance Kid lived under an alias and died in Casper, Wyoming, in 1957. But the account can’t really be trusted. Folklore about his partner Butch Cassidy’s death has him alternately dying in Vernal, Utah, in the late 1920s; on an island off the coast of Mexico in 1932; in Tombstone, Arizona, in 1937; and twice in Spokane, Washington, the same year.

**********

Hells Angels: Constant Wars — A group of B-17 bomber pilots stationed in England at the end of the Second World War called their aircraft “Hell’s Angels.” The name proved a popular one, and was picked up by other Allied fighter groups, including one that served with U.S. Marines stationed in Asia. When the Marines returned home to California, they hit the road on motorcycles together, keeping the name.

The first chapter of the Hells Angels motorcycle club appeared in 1948 in San Bernardino County, California. In 1957, Ralph “Sonny” Barger formed the Oakland chapter. The Angels made Oakland their headquarters and Barger became leader.

The Angels first displayed their colours in Canada on December 5, 1977, when the Popeyes gang, who had been warring for two years with the Satan’s Choice and the Devil’s Disciples over drug turf, became the Angels’ Montreal chapter. They immediately began to fight with the Outlaws as well, who were bitter enemies of the Angels.

This gave the Quebec Angels about three dozen members and, on July 23, 1983, the Angels expanded into British Columbia. In 1984, they absorbed the Thirteenth Tribe gang in Halifax.

A year later, in 1985, they shocked the public and other gangs by executing six members of the Laval Angels chapter for rampant drug use. The bodies of five of them were found in the St. Lawrence River, in weighted-down sleeping bags.

By the time the Montreal chapter celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary on December 5, 2002, the Canadian Hells Angels were connected to stockbrokers, bankers, and lawyers. They were particularly wealthy in British Columbia, where gang members owned such businesses as cellphone stores, stripper agencies, and porn sites on the Internet, and displayed a key interest in stock-market fraud.

Their drug-smuggling operations in Halifax, Montreal, and Vancouver were aided enormously by the federal government, which dismantled its ports police in the 1990s, despite strong warnings from major police forces, the provinces, and some of their own advisers. Authors Julian Sher and William Marsden of The Road to Hell: How the Biker Gangs Are Conquering Canada estimated in 2003 that forty-three Hells Angels and associates worked in the Port of Vancouver, at least eight of them as foremen and one as the training officer for longshoremen. Other gang members worked on docks in trucking, maintenance, laundry, and garbage service. While the Angels beefed up their presence in the ports, Ottawa simply walked away.

While Ottawa was dismantling the ports police, the Hells Angels of Quebec were proving themselves to be the most violent Angels on the planet. They were locked in the 1990s in a war with the rival Rock Machine that left some 165 people dead and another 300 injured, including innocent bystanders. The war was over control of downtown Montreal drug-trafficking networks. Angels hit man Serge Quesnel told his biographer, Pierre Martineau, that there was a businesslike ruthlessness to the gang’s murders. “I noticed that before executing a criminal, the guys would often ‘borrow’ large quantities of drugs from him. As a result, they pocketed hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

Gang members were particularly interested in gathering intelligence on potential enemies, and police in Montreal found gang members had rented a room overlooking the employee parking lot of the RCMP, using high-powered lenses to note and record licence numbers of cars coming and going.

By the end of the millennium, they spanned the country from coast to coast. Their almost six hundred Canadian members made up about a quarter of the membership of the Hells Angels around the world, and the Toronto area had the highest concentration of Angels in the world.

Also, it should be clear that this is a book about crime and criminals, not ethnic groups. There’s diversity in crime as well as in mainstream Canadian life, and organized criminals make up just a minuscule fraction of any ethnic group mentioned here. For instance, crime analysts have estimated that 0.02 per cent of the Italian-heritage community is involved in Mafia activity in Canada.

We often wondered, Why do some criminals enjoy longevity, while others don’t? One common thread shared by the successful organized criminals described in these pages is a vital link to transportation routes. To be effective for any length of time, groups have to be able to move goods and people, whether they’re taking illegal drugs to market or moving themselves — speedily — out of harm’s way. Such access to transportation routes was standard amongst the seventeenth-century pirates of the Atlantic coast, the coureurs de bois of pre-Confederation, the bootlegging gangs that followed crews building the Canadian Pacific Railway, criminals like the Sundance Kid on the Outlaw Trail of southern Saskatchewan at the turn of the twentieth century, the bootleggers of Prohibition, and, today, the cocaine cartels and the Hells Angels, with their acute interest in the shipping ports of Vancouver, Montreal, and Halifax.

But perhaps the most important central thread connecting the groups described in these pages is control of officials — either through corruption or intimidation. They all need to compromise officials in ostensibly legitimate jobs in order to function for any length of time. This was as true in the days of the early seventeenth-century pirates as it is today. Harry Longabaugh (The Sundance Kid) and his associates benefited from the assistance of a corrupt former North-West Mounted Police officer, who helped them hide out in the gullies around Big Beaver in southern Saskatchewan. Montreal mobsters Vincenzo “Vic the Egg” Cotroni and Willie Obront were called “The Untouchables” by crusading police officer Pacifique “Pax” Plante because of their excellent political connections. Maurice “Mom” Boucher of the Hells Angels took a far more brutal route to attain the same ends, using murder and the threat of violence to try to intimidate members of the judicial, legislative, and journalistic communities.

In a sense, the major criminals described in these pages weren’t really “outlaws” at all, since they needed a strong, ongoing connection to the legitimate world to survive, much like a leech or a parasite is dependent upon its host. Many tried to use their loot to buy respectability and a place in the legitimate world, and more than a few succeeded. Eric Cobham, a particularly vicious sea dog who prowled Canada’s Atlantic coast in the seventeenth century, purchased a title in the French gentry and became a magistrate, while fellow pirates Peter “The Pirate Admiral” Easton and Henry Mainwaring each bought pardons, retiring in luxury with the titles of marquis and knight, respectively. While Captain Kidd was immeasurably less violent, and didn’t even consider himself a criminal, his life ended on the gallows, as he had fallen from grace in political circles.

Organized crime is nothing new in Canada, and it was thriving 250 years before Confederation. It fuelled the adventures of fur-trading pioneers like Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Sieur des Groseilliers, known to Canadian schoolchildren as “Radishes and Gooseberries,” and the much-romanticized coureurs de bois, who operated outside the law in New France for a century before their fur-trading operation was finally made legal in 1700. The money they generated supported legitimate businesses and, in effect, propped up the economy of the early colony.

Organized crime is also present when you look at such Canadian institutions as the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Canadian Pacific Railway. Indeed, bootleggers seized control of the entire town of Michipicoten, a former Hudson’s Bay Company post on the north shore of Lake Superior in the fall of 1884, using it as their headquarters for selling booze to men working on the railway. Such activities brought to mind the saying “Steal a dollar and they throw you in jail. Steal a million and they make you king.”

Even the Hells Angels biker gang isn’t comfortable with a totally outlaw image. They obviously crave a certain legitimacy, which explains the controversial public handshake between a biker and former Toronto mayor Mel Lastman in January 2002; Maurice “Mom” Boucher posing for a photo with an unwitting Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa; or a group of Angels posing for photos with Montreal Canadiens’ goalie Jose Theodore or with Pat Burns, back when Burns coached the Toronto Maple Leafs of the National Hockey League. At times, the Angels’ actions look like a sad effort to push themselves into “respectable” society.

While we’ve drawn up a fairly long list in this overview of names in Canadian organized crime, we don’t pretend it’s complete. Some readers may wonder how Woody the Biker Lion or Pearl Hart made the list and others didn’t. We admit that a few entries appear here more for quirkiness than for their organizational skills. In general, however, we were biased toward highly structured groups, which explains why there’s more on the Hells Angels and the Mafia than the more loosely-knit Jamaican posses and Vietnamese street gangs. Barring a sudden change in human nature, there will undoubtedly be plenty more additions for future editions.

**********

The Sundance Kid: Alberta Ranch Hand — His real name was Harry Alonzo Longabaugh and he also answered to Harry Place and Frank Boyd, but he’s best known as the character played by Robert Redford in the 1969 movie Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

What’s not so well known are his Canadian roots, and that he often hid out in southern Saskatchewan and lived in Alberta from 1890 to 1892, when he was in his early to mid-twenties. Longabaugh didn’t advertise his nickname — The Sundance Kid — and certainly no one asked about it when he showed up to work as a cowboy for the North-West Cattle Company — known as the “Bar U” — west of High River, Alberta.

He got the nickname when, as a youth, he served an eighteen-month jail term in Sundance, Wyoming, for stealing a horse, a saddle, and a gun from a ranch worker in Crook County, Wyoming, when he was either sixteen or seventeen years old. Upon his release from jail on February 8, 1889, the Sundance Gazette noted that, “The term of ‘kid’ Longabaugh has expired.” From then on, he was known as the Sundance Kid.

Longabaugh returned to Colorado, where he had lived with a distant cousin, and joined Robert Leroy Parker (a.k.a. Butch Cassidy), Tom McCarty, and Matt Warner in holding up the San Miguel Valley Bank in Telluride on June 24, 1889. After that, he needed a new safe haven, and fled north to Canada in time for the 1890 cattle season.

There he looked up an old friend from Wyoming, Cyril Everett “Ebb” Johnson, who lived in the Cochrane, Alberta, area. They had worked together earlier in Wyoming at the Power River Ranch, which expanded into Canada in 1886, leasing land on Mosquito Creek, near where the town of Nanton is today. It had the brand of “76” and that was its local nickname.

Johnson was foreman of the “Bar U,” which had 10,410 cattle and 832 horses in 1890. Sundance quickly proved to be a valuable employee, as well as a popular one. Fred Ings of the nearby Midway Ranch noted that “a thoroughly likeable fellow was Harry, a general favorite with everyone, a splendid rider and a top notch cow hand.” Ings also said that the Kid was law-abiding and “no one could have been better behaved or more decent.”

Ings had reason to say nice things about him, since he believed the Sundance Kid saved his life during a fall roundup. “One . . . night on Mosquito Creek was one of the worst times I ever went through. A blizzard was coming from the north with blinding snow. I was given the ten o’clock shift, and with me was Harry Longdebough [sic], a good-looking young American cow puncher who feared neither man nor devil.”

The herd was large, made up mostly of heavy beef cattle. Sundance drove ahead to direct them while Ings stayed at the back to hold them together.

Ings continued: “I was riding a sure-footed, thick-set, little grey horse, but I had a dozen falls that stormy night. In spite of being warmly dressed, we found it desperately cold and in the thickly falling snow lost all sense of locality.”

The Sundance Kid rode back to find Ings lost at the rear of the herd, and helped guide him back to camp, likely saving his life.

Rancher Bert Sheppard also had a high opinion of Sundance, describing him as “a good rider, roper and all-round top hand.” Most of his acquaintances seemed to know he had been in trouble in the United States, but he was fully accepted because of his ability and his friendly attitude.

He also worked for the McHugh Brothers at the H2 Ranch, on the Bow River near Carseland, Alberta, where they had a contract to supply beef to the nearby Blackfoot reserve. Also while in Alberta, he was believed to have worked breaking horses for contractors who were laying the railroad from Calgary to Fort MacLeod.

He appeared in the spring 1891 Dominion Census, District No. 197. The Bar U Ranch was enumerated on April 6, 1891, with eighteen residents, including “Henry Longabough [sic], age 25, birthplace U.S.A., occupation horse breaker.”

Not everyone liked him. A cowboy at the Bar U, Herbert Millar, claimed that he saw a small hacksaw hidden between Sundance’s saddle and his horse blanket. This may be tied to his arrest by the North-West Mounted Police for “cruelty to animals” on August 7, 1891. Sundance hired a lawyer, J.A. Bangs, and the charges were immediately dismissed the same day by Super intendent J.H. McIllree and Inspector A.R. Cuthbert. No explanation was given for their immediate dismissal. He was kept on at Bar U, suggesting the ranch’s owners did not believe the charges of animal cruelty had any factual foundation.

On November 18, 1891, Sundance signed as the witness and best man at the wedding of his friend Ebb Johnson and his bride, Mary Eleanor Bigland, at The Grange, a Calgary-area ranch owned by her uncle, with Rev. J.C. Herdman of Knox Presbyterian Church in Calgary presiding.

Some time after the wedding, Sundance left the Bar U, perhaps because Millar, who had pushed the cruelty to animals charges, had become the foreman there. He went into partnership with Frank Hamilton at the Grand Central Hotel saloon on Atlantic Avenue in Calgary, across the street from the railway depot. There are unverified reports that Butch Cassidy visited Calgary during that time, and that he even may have worked at a Calgary livery stable.

The partnership between Sundance and Hamilton didn’t last long, and ended in gunplay. Hamilton had a reputation for taking in partners and then choosing to fight them rather than hand over their share of the profits.

Sundance wouldn’t be intimidated. Author Vicky Kelly said that he vaulted over the bar and “before his feet hit the floor his gun was jammed in his partner’s middle.” The debt was paid, but the partnership was over, and early in 1892, Sundance returned to the United States.

There, he soon hooked up with rustlers Dutch Henry Ieach and Frank Jones, and together they ran stolen horses from the Culbertson and Plentywood area of Montana across into the Big Muddy Badlands of southern Saskatchewan, near the community of Big Beaver. It was the first stop on the Outlaw Trail, a string of safe havens stretching down to Mexico. This one was particularly safe, because American authorities could not cross the border into Canada.

Sundance joined a band of about ten outlaws called the Wild Bunch, who thrived from 1896 through 1901, and whose ranks included Robert Leroy Parker (Butch Cassidy). Sometimes the gang included Bill Curry, an outlaw originally from Prince Edward Island.

The Wild Bunch robbed banks and slow-moving, cash-carrying trains, but perhaps their proudest moment came on September 19, 1900, after they held up the First National Bank in Winnemucca, Nevada. They made off with $30,000, and legend has it they headed for Fort Worth, Texas, where they posed for a group photograph, then mailed it to the bank, with a note of thanks for the “withdrawal.”

Often, in times of stress, Sundance retreated to the Big Beaver area of southern Saskatchewan. He had fled there after the November 29, 1892, robbery of a Great Northern Railway train at Malta, Montana, and a police report from the time speculated he may have also gone to Calgary to visit Ebb Johnson.

However, times changed. Trains got faster and private security companies got more efficient, and ultimately Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid ended up in Bolivia. A 1909 report said that Sundance and Butch were killed there by a posse after a payroll robbery. News of his robberies filtered up to the Calgary area, where he had many friends. Fred Ings wrote, “We all felt sorry when he left and got in bad again across the line.”

Another story, promoted by Cassidy’s sister, was that the Sundance Kid lived under an alias and died in Casper, Wyoming, in 1957. But the account can’t really be trusted. Folklore about his partner Butch Cassidy’s death has him alternately dying in Vernal, Utah, in the late 1920s; on an island off the coast of Mexico in 1932; in Tombstone, Arizona, in 1937; and twice in Spokane, Washington, the same year.

**********

Hells Angels: Constant Wars — A group of B-17 bomber pilots stationed in England at the end of the Second World War called their aircraft “Hell’s Angels.” The name proved a popular one, and was picked up by other Allied fighter groups, including one that served with U.S. Marines stationed in Asia. When the Marines returned home to California, they hit the road on motorcycles together, keeping the name.

The first chapter of the Hells Angels motorcycle club appeared in 1948 in San Bernardino County, California. In 1957, Ralph “Sonny” Barger formed the Oakland chapter. The Angels made Oakland their headquarters and Barger became leader.

The Angels first displayed their colours in Canada on December 5, 1977, when the Popeyes gang, who had been warring for two years with the Satan’s Choice and the Devil’s Disciples over drug turf, became the Angels’ Montreal chapter. They immediately began to fight with the Outlaws as well, who were bitter enemies of the Angels.

This gave the Quebec Angels about three dozen members and, on July 23, 1983, the Angels expanded into British Columbia. In 1984, they absorbed the Thirteenth Tribe gang in Halifax.

A year later, in 1985, they shocked the public and other gangs by executing six members of the Laval Angels chapter for rampant drug use. The bodies of five of them were found in the St. Lawrence River, in weighted-down sleeping bags.

By the time the Montreal chapter celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary on December 5, 2002, the Canadian Hells Angels were connected to stockbrokers, bankers, and lawyers. They were particularly wealthy in British Columbia, where gang members owned such businesses as cellphone stores, stripper agencies, and porn sites on the Internet, and displayed a key interest in stock-market fraud.

Their drug-smuggling operations in Halifax, Montreal, and Vancouver were aided enormously by the federal government, which dismantled its ports police in the 1990s, despite strong warnings from major police forces, the provinces, and some of their own advisers. Authors Julian Sher and William Marsden of The Road to Hell: How the Biker Gangs Are Conquering Canada estimated in 2003 that forty-three Hells Angels and associates worked in the Port of Vancouver, at least eight of them as foremen and one as the training officer for longshoremen. Other gang members worked on docks in trucking, maintenance, laundry, and garbage service. While the Angels beefed up their presence in the ports, Ottawa simply walked away.

While Ottawa was dismantling the ports police, the Hells Angels of Quebec were proving themselves to be the most violent Angels on the planet. They were locked in the 1990s in a war with the rival Rock Machine that left some 165 people dead and another 300 injured, including innocent bystanders. The war was over control of downtown Montreal drug-trafficking networks. Angels hit man Serge Quesnel told his biographer, Pierre Martineau, that there was a businesslike ruthlessness to the gang’s murders. “I noticed that before executing a criminal, the guys would often ‘borrow’ large quantities of drugs from him. As a result, they pocketed hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

Gang members were particularly interested in gathering intelligence on potential enemies, and police in Montreal found gang members had rented a room overlooking the employee parking lot of the RCMP, using high-powered lenses to note and record licence numbers of cars coming and going.

By the end of the millennium, they spanned the country from coast to coast. Their almost six hundred Canadian members made up about a quarter of the membership of the Hells Angels around the world, and the Toronto area had the highest concentration of Angels in the world.

Recenzii

"With admirable diligence and dispatch, the authors harmonize the multiple solitudes that make up this vast nation into one fascinating, readable tome of transgression and terror." -- Globe and Mail