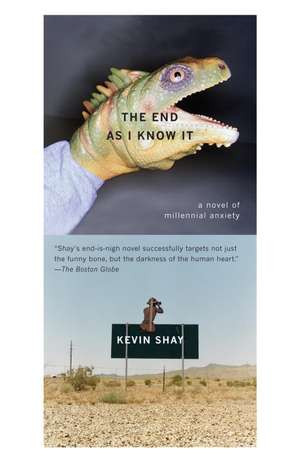

The End as I Know It: A Novel of Millenial Anxiety

Autor Kevin Shayen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2008

It's 1998. Randall, a twenty-five-year-old children's singer and puppeteer, has discovered the clock is ticking toward a worldwide technological cataclysm. But he may be able to save his loved ones-if he can convince them to prepare for the looming threat. That's why he's quit his job, moved into his car, and set out to sound the alarm. The End As I Know It follows Randall on his poignant and funny coast-to-coast Cassandra tour.

Preț: 87.60 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 131

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.78€ • 17.29$ • 14.05£

16.78€ • 17.29$ • 14.05£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 februarie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307276728

ISBN-10: 0307276724

Pagini: 371

Dimensiuni: 137 x 203 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0307276724

Pagini: 371

Dimensiuni: 137 x 203 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Kevin Shay's humor writing has appeared in print and online in McSweeney's, eCompany Now, Salon, Modern Humorist, and the anthology 101 Damnations. He was the online editor of McSweeney's in 2000 and 2001 and recently co-edited Created in Darkness by Troubled Americans, a collection of humor pieces from the site. He lives in New York.

Extras

Chapter 1

450 Days

Cutting through six layers of hangover and hideous dream, a no-nonsense knock on the door. “ ’Ousekeeping!” Must have forgotten to hang the do not disturb again. “ ’Ousekeeping!” A booming Caribbean contralto. The handle turning. But aha, I remembered the chain, which—clank!—thwarts the maid's entry. “Clean y’room?” she bellows through the crack. “Later, please,” I find it in me to croak.

She retreats. I like this maid—encountered her yesterday as I was checking in. A fiftyish hillside of a lady with steak–sized hands that make short work of motel detritus. Probably has five to seven children and cousins uncountable. If they’re the close-knit family I envision, if they have a good community around them—where am I, Illinois? Bet they have some good communities here—if they can lie low and hang together through the first few months, I like to think she and hers might make it to the other side.

Ah, who am I kidding? She’s a goner. Too bad. It crosses my mind to drop a little knowledge on her, but coming from some bleary–eyed white boy holed up in a room she only wants to tidy, it would never take. Maybe if her husband or her pastor wises up in time, she can be convinced. She seems sensible. Oh well—I can’t save everyone.

About time to pack up and check out, though I’d love to spend another day, nap until early afternoon and then drive into whatever passes for town around here. Take a stroll, grab a grilled cheese and fries, then retire to these antiseptic quarters with maybe some Doritos and a fresh bottle of Cuervo. Pass out, wake, repeat. But the deadline looms, the ironclad terrible deadline. No slots for sloth penciled into my calendar, and my plan, windpissing though it may be, is all I’ve got going. I can relax in, say, 2002, on the off chance I’m still alive.

I stand at the sink and grimace at my reflection. Underfed and out of shape, an unimpressive torso sheathed in a shrunken fraying T–shirt bearing the faded logo of some band my ex–girlfriend used to like, puffy pockets under my dry pink eyes. A drifter, that’s what I look like, the kind the police in movies are always searching for in connection with an incident. I do what can be done with my unruly ash–brown curls. Should shower, should drink water, but both prospects repel me. Is this hydrophobia? Man, rabies is the last thing I need. But no, that would require contact with wildlife of some kind. Except for speeding by roadkill, I’ve barely laid eyes on any fauna for weeks. And damn little flora, for that matter. Sounds like a Broadway musical: Damn Little Flora. I extemporize a refrain, Cole Porterwise, while taking a futile brush to my hair: “Hey! You’re in a jam, Little Flora. Too bad! You’re on the lam, Little Flora. All I can say is, Damn, Little Flora! Goodbyeeeee.”

Let’s see, when’s checkout? A chintzy ten–thirty, giving me a half-hour to gather my wits and belongings. Normally I bring at least the guitars and puppets into the room, but no thief would bother to hit the parking lot of this generic Super 8 off a down–at–heels section of interstate, so last night I rolled the dice and left everything in the car but the small duffel bag.

OK, time to get my bearings. I sit down on the bed and lay out the components of the makeshift TripTik for my coast–to–coast Cassandra tour. My trusty road atlas. My itinerary, penciled on pages torn from a wall calendar given away by a Century 21 agent in a town I’ve never been to. And my list of names. Looking at this list used to energize me. Not so much anymore, as the column of X’s to the left of the names marches further down the page. Eight down, eight to go. Halfway through my nearest and dearest, and only one checkmark—Grandma, my most recent attempt and sole success, a few days ago in Boca Raton. But hey, I’m on a one–game winning streak. Next on the list, Damien, my best friend from college, who now warms a carrel under the auspices of the Ancient Mediterranean World Department at the University of Chicago. Maybe he’ll be an easy sell. A student of the Roman Empire ought to fathom how civilizations can collapse under their own weight. Although spending his days among tomes in dead tongues might have rendered him blind to the doomed silicon engine that drives the present-day world. Could go either way.

I open my atlas and with eyes and index finger trace and retrace the route between here and Damien’s address until it starts to sink in. Once I’m reasonably confident I can find my way to Chicago, I pick up the phone, punch a baroque sequence of calling–card digits, and wait for my manager to pick up. Which he will. I’ve never once failed to get Gene Denley on the phone on the first try, at any hour of the day. This strikes me as unseemly for a manager.

“Denley Associates.” That slow, soothing voice, giving the “so” in “Associates” that diphthongal pronunciation I initially took for Southern but later learned is pre–urban–blight Bronx. There are no associates. Gene works alone, as he has in four or five prior careers, none of which held his interest. Layers of yellowing paperwork from all these enterprises threaten to burst the seams of his little Somerville office. Another of his clients, a clown, told me she’d heard he was independently wealthy, his businesses a succession of larks. Well, if Gene has money, he hides it well.

“It's Randall,” I say.

“Randall! You're in Chicago?”

“Or thereabouts.”

“Your parents are trying to reach you, kid.”

“Both of them?”

“I wish you'd get a damn cell phone. Hell, I’d pay for it.”

He makes this offer frequently because he knows I'll refuse. This time, to tweak him, I feign interest.

“Really? You’d do that for me, Gene?”

He backpedals instantly. “Well, I could maybe help out with the phone itself. The service, you’re on your own.”

“Forget it. So who called?”

“Mom yesterday, and stepdad the day before that.”

Fishy. Ted wouldn’t call unless something was wrong with Mom, and in that case he would’ve told Gene about it. “Are you sure it was my stepfather? What number did he leave?”

“Eight hundred something. Where is it …”

I wince. My father must have signed up for a toll–free number just for this purpose. Thought I wouldn’t recognize the number, so I’d call. Sad, albeit resourceful.

“That's gotta be Dad, sneaking up on me.”

Gene sighs. “Look, just call the poor guy, why don't you? Life’s too short to burn bridges.” He doesn’t sound like he really believes this. I have a feeling Gene’s a bridge–burner from way back.

“Gene, I have a checkout time. Can we talk schedule?”

“All right. Don’t say I didn't try. So let’s see. Nothing much new. Tentatives in Connecticut and Vermont on December fourth and eighth.” As if a switch had been thrown, he’s gone from avuncular to efficient, the gentle drawl replaced by clipped consonants and a let’s–get–this–done cadence, what I think of as his public school persona. He flips between these two modes as needed. When dealing with public schools, he’s generally selling bean–counters on my affordability as a surefire crowd–pleaser and takes the businesslike tone. Pitching me to private schools, he deals with doe–eyed kindergarten teachers and educational idealists and sticks with the lulling geniality as he hawks my intangible crunchy–feeliness, talking about oral tradition and campfires and Burl Ives.

“Any checks come in yet?”

“Nah. Your first booking was what, the week after Labor Day? Listen, when these people say net thirty they don't mean net twenty-nine.”

“I hear you.”

“You got enough cash for the next couple weeks?”

“I think I'm OK. Thanks.” Gene doesn’t know I'm still flush from selling my furniture, CDs, books, computer, TV, stereo, and all my music gear except the two acoustics I perform with. I’m not even halfway through the proceeds, and that plus the gig money should keep me above the waterline until things start to go south. Or, Plan B, I’ll run my credit cards up to their meager limits, since I doubt the issuing banks will be around long enough to collect.

I hang up with Gene and throw my stuff into the bag. Two bucks on the dresser for the maid. I open the nightstand drawer. Inside, a dried-out cockroach corpse lies on top of the Holy Bible. I pick the Bible up by one corner and shake the bug off, then stick the book into my bag. Into the drawer I place a copy of Time Bomb 2000: What the Year 2000 Computer Crisis Means to You. I started off with a full box of these in the car. The box is now about one third Gideon Bibles.

My good deed for the day. I picture a weary business traveler, on his way from a sales pitch in Rockford to another in Tulsa, idly opening this drawer, a week or three months from now. Surprised to find no Bible, he takes out the unexpected book and flips through a few pages. Some fact or another catches his eye. The number of power generation facilities in North America, maybe, or the failure rate of software development projects. Then he begins to read in earnest, his heart beating faster. Could this be for real? He goes back and starts reading from page one. He gets no sleep, devouring the book until the middle of the night and then tossing and turning as he tries to cope with what he's learned. In the morning he calls Tulsa to cancel and races toward home—the Twin Cities, say—where he'll do some online research and then gather his family for a very serious talk. On the path to preparedness, all thanks to me.

Well, stranger things have happened.

* * *

Mired in traffic on a so–called expressway, I glean from the signage that I have reached, if not Chicago, “Chicagoland,” which sounds like an ill–conceived theme park. Ride the Al Capone Cyclone. Nearly noon, rush hour long done by any sane definition, so why are we stuttering along, my speedometer needle lucky to nudge 5? At this pace I’d stew in exhaust fumes with the windows open, so I have the air on even though it’s not so hot out and I’m probably pouring CFCs into the environment. When did the Clean Air Act take effect? The AC in my 1992 Oldsmobile Custom Cruiser is probably one of the old dirty ones. Well, no need to worry about the ozone layer anymore. All the direr ecological models assume many more years of unabated industrial activity, which is not bloody likely.

One ongoing debate on the message boards is whether droves of terrified urbanites will pour out of the cities toward safer ground in 1999, or whether they’ll wait until the systems actually go down. One school of thought considers city–dwellers too smug and oblivious to make a move until anarchy reigns. The other camp foresees that at some point in ’99 the lookahead failures, imploding world markets, bad remediation reports, and miscellaneous madness will hit critical mass and spark a general exodus. I could see this being triggered by, say, one powerful report on Dateline or 60 Minutes. That’s how this world is moved, not by scientific truths but by Stone Phillips or Mike Wallace acknowledging them publicly. Global warming, for instance, was nothing until Nightline got hold of it one evening in the late eighties in the middle of a record-setting heat wave. I remember it well. Sean McDonough and Bob Montgomery had just finished calling the Red Sox game on Channel 38. I turned the dial on the tiny remoteless black-and-white in my bedroom and landed on Koppel, interviewing one James Hansen of NASA on his outlandish theory about greenhouse gas. And from that point on, everyone seemed to know what global warming was, even if they didn't believe in it. They form our minds, these newscasters, they shape the world. One high-profile Y2K snafu plus a nudge from Brokaw or Jennings could get people running.

At the moment, crawling snailwise along an Illinois highway, I hope to hell that if there is a flight from the cities, it’ll at least happen gradually. These arteries can barely carry a normal weekday’s load of commuters in and out of town. Everyone trying to leave at once is a surefire recipe for a fatal clot. And if it happens after the emergencies outnumber the emergency services, we’re talking permanent gridlock, as dozens, then thousands, abandon their useless cars and start walking. Do they press on away from the city or trudge home to await their fate? Depends how cold the weather, how bad the news on the radio if anyone’s still broadcasting. Families with young or old or sick members won't make it far. Children, grandparents will die waiting for help right here, right here along this highway—

The driver behind me blasts his horn. Must’ve closed my eyes at some point, and the car in front of me has advanced a few precious yards. I follow suit and survey the landscape. A nondescript congested highway on a bright autumn day. Mildly annoyed drivers, a cloud–speckled sky. My nightmare vision of mothers wailing for insulin and Hondas aflame for warmth fades to a ludicrous fantasy. And that’s the problem, really. To the woman in the Ford Fiesta on my right, to the couple in the Ford Escort on my left, the way things are is the only way things could be. Until one day it’s different. Koppel shows a hint of fear, America smells it, and then everything changes and cadavers litter the Dan Ryan Expressway.

Finally I pass the culprit, an Acura with a blown tire in the left lane. To think a faulty piece of galvanized rubber can delay hundreds of people for an hour. Such an outsized effect for such a tiny cause. No tinier, though, than a few lines of computer code, a few stray electrons.

Beyond the bottleneck, we start to move at a healthy clip. I turn on the radio and find a news station. Congress is wrestling with momentous blow–job–related issues. For a decade the government has piloted the ship of state directly toward a gargantuan iceberg floating in plain sight, and all anyone wants to talk about is the president's semen and where it went.

Hundreds of years from now, the scholars of whatever society arises from the ruins of ours will look back on this moment in history and proclaim:

“What the fuck was that?”

* * *

“Whoa! Big place!”

Damien’s loft is enormous, all right, but its outlandish condition is what’s put the astonishment in my voice. He warned me about the socialists he lives with—that must be some of them huddled around the TV—but said nothing to prepare me for this fantastic squalor.

“That's my room up there.” Damien points to a nonchalantly lofted three–walled room that sits over a bathroom and looks out onto the large central area we’re standing in. The rest of the cavernous place is haphazardly partitioned by unpainted drywall, with not a right angle in sight. Books, stacks of newspapers, ashtrays (full), beer bottles (ashtrays of last resort), and empty snack–food packaging cover every possible surface in the common area—“living room” seems generous. In the far corner, a shocking kitchen, the sink and countertops overflowing with mismatched dirty dishes. It’s like a movie where some character is mentally ill, and this is the scene where her son walks into her house, gasps at how far her condition has deteriorated, and realizes she’s unable to care for herself.

From the Hardcover edition.

450 Days

Cutting through six layers of hangover and hideous dream, a no-nonsense knock on the door. “ ’Ousekeeping!” Must have forgotten to hang the do not disturb again. “ ’Ousekeeping!” A booming Caribbean contralto. The handle turning. But aha, I remembered the chain, which—clank!—thwarts the maid's entry. “Clean y’room?” she bellows through the crack. “Later, please,” I find it in me to croak.

She retreats. I like this maid—encountered her yesterday as I was checking in. A fiftyish hillside of a lady with steak–sized hands that make short work of motel detritus. Probably has five to seven children and cousins uncountable. If they’re the close-knit family I envision, if they have a good community around them—where am I, Illinois? Bet they have some good communities here—if they can lie low and hang together through the first few months, I like to think she and hers might make it to the other side.

Ah, who am I kidding? She’s a goner. Too bad. It crosses my mind to drop a little knowledge on her, but coming from some bleary–eyed white boy holed up in a room she only wants to tidy, it would never take. Maybe if her husband or her pastor wises up in time, she can be convinced. She seems sensible. Oh well—I can’t save everyone.

About time to pack up and check out, though I’d love to spend another day, nap until early afternoon and then drive into whatever passes for town around here. Take a stroll, grab a grilled cheese and fries, then retire to these antiseptic quarters with maybe some Doritos and a fresh bottle of Cuervo. Pass out, wake, repeat. But the deadline looms, the ironclad terrible deadline. No slots for sloth penciled into my calendar, and my plan, windpissing though it may be, is all I’ve got going. I can relax in, say, 2002, on the off chance I’m still alive.

I stand at the sink and grimace at my reflection. Underfed and out of shape, an unimpressive torso sheathed in a shrunken fraying T–shirt bearing the faded logo of some band my ex–girlfriend used to like, puffy pockets under my dry pink eyes. A drifter, that’s what I look like, the kind the police in movies are always searching for in connection with an incident. I do what can be done with my unruly ash–brown curls. Should shower, should drink water, but both prospects repel me. Is this hydrophobia? Man, rabies is the last thing I need. But no, that would require contact with wildlife of some kind. Except for speeding by roadkill, I’ve barely laid eyes on any fauna for weeks. And damn little flora, for that matter. Sounds like a Broadway musical: Damn Little Flora. I extemporize a refrain, Cole Porterwise, while taking a futile brush to my hair: “Hey! You’re in a jam, Little Flora. Too bad! You’re on the lam, Little Flora. All I can say is, Damn, Little Flora! Goodbyeeeee.”

Let’s see, when’s checkout? A chintzy ten–thirty, giving me a half-hour to gather my wits and belongings. Normally I bring at least the guitars and puppets into the room, but no thief would bother to hit the parking lot of this generic Super 8 off a down–at–heels section of interstate, so last night I rolled the dice and left everything in the car but the small duffel bag.

OK, time to get my bearings. I sit down on the bed and lay out the components of the makeshift TripTik for my coast–to–coast Cassandra tour. My trusty road atlas. My itinerary, penciled on pages torn from a wall calendar given away by a Century 21 agent in a town I’ve never been to. And my list of names. Looking at this list used to energize me. Not so much anymore, as the column of X’s to the left of the names marches further down the page. Eight down, eight to go. Halfway through my nearest and dearest, and only one checkmark—Grandma, my most recent attempt and sole success, a few days ago in Boca Raton. But hey, I’m on a one–game winning streak. Next on the list, Damien, my best friend from college, who now warms a carrel under the auspices of the Ancient Mediterranean World Department at the University of Chicago. Maybe he’ll be an easy sell. A student of the Roman Empire ought to fathom how civilizations can collapse under their own weight. Although spending his days among tomes in dead tongues might have rendered him blind to the doomed silicon engine that drives the present-day world. Could go either way.

I open my atlas and with eyes and index finger trace and retrace the route between here and Damien’s address until it starts to sink in. Once I’m reasonably confident I can find my way to Chicago, I pick up the phone, punch a baroque sequence of calling–card digits, and wait for my manager to pick up. Which he will. I’ve never once failed to get Gene Denley on the phone on the first try, at any hour of the day. This strikes me as unseemly for a manager.

“Denley Associates.” That slow, soothing voice, giving the “so” in “Associates” that diphthongal pronunciation I initially took for Southern but later learned is pre–urban–blight Bronx. There are no associates. Gene works alone, as he has in four or five prior careers, none of which held his interest. Layers of yellowing paperwork from all these enterprises threaten to burst the seams of his little Somerville office. Another of his clients, a clown, told me she’d heard he was independently wealthy, his businesses a succession of larks. Well, if Gene has money, he hides it well.

“It's Randall,” I say.

“Randall! You're in Chicago?”

“Or thereabouts.”

“Your parents are trying to reach you, kid.”

“Both of them?”

“I wish you'd get a damn cell phone. Hell, I’d pay for it.”

He makes this offer frequently because he knows I'll refuse. This time, to tweak him, I feign interest.

“Really? You’d do that for me, Gene?”

He backpedals instantly. “Well, I could maybe help out with the phone itself. The service, you’re on your own.”

“Forget it. So who called?”

“Mom yesterday, and stepdad the day before that.”

Fishy. Ted wouldn’t call unless something was wrong with Mom, and in that case he would’ve told Gene about it. “Are you sure it was my stepfather? What number did he leave?”

“Eight hundred something. Where is it …”

I wince. My father must have signed up for a toll–free number just for this purpose. Thought I wouldn’t recognize the number, so I’d call. Sad, albeit resourceful.

“That's gotta be Dad, sneaking up on me.”

Gene sighs. “Look, just call the poor guy, why don't you? Life’s too short to burn bridges.” He doesn’t sound like he really believes this. I have a feeling Gene’s a bridge–burner from way back.

“Gene, I have a checkout time. Can we talk schedule?”

“All right. Don’t say I didn't try. So let’s see. Nothing much new. Tentatives in Connecticut and Vermont on December fourth and eighth.” As if a switch had been thrown, he’s gone from avuncular to efficient, the gentle drawl replaced by clipped consonants and a let’s–get–this–done cadence, what I think of as his public school persona. He flips between these two modes as needed. When dealing with public schools, he’s generally selling bean–counters on my affordability as a surefire crowd–pleaser and takes the businesslike tone. Pitching me to private schools, he deals with doe–eyed kindergarten teachers and educational idealists and sticks with the lulling geniality as he hawks my intangible crunchy–feeliness, talking about oral tradition and campfires and Burl Ives.

“Any checks come in yet?”

“Nah. Your first booking was what, the week after Labor Day? Listen, when these people say net thirty they don't mean net twenty-nine.”

“I hear you.”

“You got enough cash for the next couple weeks?”

“I think I'm OK. Thanks.” Gene doesn’t know I'm still flush from selling my furniture, CDs, books, computer, TV, stereo, and all my music gear except the two acoustics I perform with. I’m not even halfway through the proceeds, and that plus the gig money should keep me above the waterline until things start to go south. Or, Plan B, I’ll run my credit cards up to their meager limits, since I doubt the issuing banks will be around long enough to collect.

I hang up with Gene and throw my stuff into the bag. Two bucks on the dresser for the maid. I open the nightstand drawer. Inside, a dried-out cockroach corpse lies on top of the Holy Bible. I pick the Bible up by one corner and shake the bug off, then stick the book into my bag. Into the drawer I place a copy of Time Bomb 2000: What the Year 2000 Computer Crisis Means to You. I started off with a full box of these in the car. The box is now about one third Gideon Bibles.

My good deed for the day. I picture a weary business traveler, on his way from a sales pitch in Rockford to another in Tulsa, idly opening this drawer, a week or three months from now. Surprised to find no Bible, he takes out the unexpected book and flips through a few pages. Some fact or another catches his eye. The number of power generation facilities in North America, maybe, or the failure rate of software development projects. Then he begins to read in earnest, his heart beating faster. Could this be for real? He goes back and starts reading from page one. He gets no sleep, devouring the book until the middle of the night and then tossing and turning as he tries to cope with what he's learned. In the morning he calls Tulsa to cancel and races toward home—the Twin Cities, say—where he'll do some online research and then gather his family for a very serious talk. On the path to preparedness, all thanks to me.

Well, stranger things have happened.

* * *

Mired in traffic on a so–called expressway, I glean from the signage that I have reached, if not Chicago, “Chicagoland,” which sounds like an ill–conceived theme park. Ride the Al Capone Cyclone. Nearly noon, rush hour long done by any sane definition, so why are we stuttering along, my speedometer needle lucky to nudge 5? At this pace I’d stew in exhaust fumes with the windows open, so I have the air on even though it’s not so hot out and I’m probably pouring CFCs into the environment. When did the Clean Air Act take effect? The AC in my 1992 Oldsmobile Custom Cruiser is probably one of the old dirty ones. Well, no need to worry about the ozone layer anymore. All the direr ecological models assume many more years of unabated industrial activity, which is not bloody likely.

One ongoing debate on the message boards is whether droves of terrified urbanites will pour out of the cities toward safer ground in 1999, or whether they’ll wait until the systems actually go down. One school of thought considers city–dwellers too smug and oblivious to make a move until anarchy reigns. The other camp foresees that at some point in ’99 the lookahead failures, imploding world markets, bad remediation reports, and miscellaneous madness will hit critical mass and spark a general exodus. I could see this being triggered by, say, one powerful report on Dateline or 60 Minutes. That’s how this world is moved, not by scientific truths but by Stone Phillips or Mike Wallace acknowledging them publicly. Global warming, for instance, was nothing until Nightline got hold of it one evening in the late eighties in the middle of a record-setting heat wave. I remember it well. Sean McDonough and Bob Montgomery had just finished calling the Red Sox game on Channel 38. I turned the dial on the tiny remoteless black-and-white in my bedroom and landed on Koppel, interviewing one James Hansen of NASA on his outlandish theory about greenhouse gas. And from that point on, everyone seemed to know what global warming was, even if they didn't believe in it. They form our minds, these newscasters, they shape the world. One high-profile Y2K snafu plus a nudge from Brokaw or Jennings could get people running.

At the moment, crawling snailwise along an Illinois highway, I hope to hell that if there is a flight from the cities, it’ll at least happen gradually. These arteries can barely carry a normal weekday’s load of commuters in and out of town. Everyone trying to leave at once is a surefire recipe for a fatal clot. And if it happens after the emergencies outnumber the emergency services, we’re talking permanent gridlock, as dozens, then thousands, abandon their useless cars and start walking. Do they press on away from the city or trudge home to await their fate? Depends how cold the weather, how bad the news on the radio if anyone’s still broadcasting. Families with young or old or sick members won't make it far. Children, grandparents will die waiting for help right here, right here along this highway—

The driver behind me blasts his horn. Must’ve closed my eyes at some point, and the car in front of me has advanced a few precious yards. I follow suit and survey the landscape. A nondescript congested highway on a bright autumn day. Mildly annoyed drivers, a cloud–speckled sky. My nightmare vision of mothers wailing for insulin and Hondas aflame for warmth fades to a ludicrous fantasy. And that’s the problem, really. To the woman in the Ford Fiesta on my right, to the couple in the Ford Escort on my left, the way things are is the only way things could be. Until one day it’s different. Koppel shows a hint of fear, America smells it, and then everything changes and cadavers litter the Dan Ryan Expressway.

Finally I pass the culprit, an Acura with a blown tire in the left lane. To think a faulty piece of galvanized rubber can delay hundreds of people for an hour. Such an outsized effect for such a tiny cause. No tinier, though, than a few lines of computer code, a few stray electrons.

Beyond the bottleneck, we start to move at a healthy clip. I turn on the radio and find a news station. Congress is wrestling with momentous blow–job–related issues. For a decade the government has piloted the ship of state directly toward a gargantuan iceberg floating in plain sight, and all anyone wants to talk about is the president's semen and where it went.

Hundreds of years from now, the scholars of whatever society arises from the ruins of ours will look back on this moment in history and proclaim:

“What the fuck was that?”

* * *

“Whoa! Big place!”

Damien’s loft is enormous, all right, but its outlandish condition is what’s put the astonishment in my voice. He warned me about the socialists he lives with—that must be some of them huddled around the TV—but said nothing to prepare me for this fantastic squalor.

“That's my room up there.” Damien points to a nonchalantly lofted three–walled room that sits over a bathroom and looks out onto the large central area we’re standing in. The rest of the cavernous place is haphazardly partitioned by unpainted drywall, with not a right angle in sight. Books, stacks of newspapers, ashtrays (full), beer bottles (ashtrays of last resort), and empty snack–food packaging cover every possible surface in the common area—“living room” seems generous. In the far corner, a shocking kitchen, the sink and countertops overflowing with mismatched dirty dishes. It’s like a movie where some character is mentally ill, and this is the scene where her son walks into her house, gasps at how far her condition has deteriorated, and realizes she’s unable to care for herself.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Shay takes The End as I Know It into sublimely multilayered directions.” —Los Angeles Times“[The End As I Know It] provides readers with one picaresque, laugh-out-loud funny scene after another. . . . Shay's end-is-nigh novel successfully targets not just the funny bone, but the darkness of the human heart.” —The Boston Globe“Shay endows his main character . . . with the sharp wit one would expect from a McSweeney's alum.” —San Francisco Chronicle“That Randall is charming and appealing even as he alienates everyone he loves is a testament to Shay's light and witty touch with his nutty hero. . . . Shay is a first novelist not to be dismissed.” —USA Today