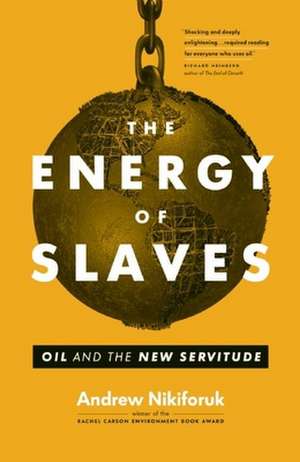

The Energy of Slaves: David Suzuki Institute

Autor Andrew Nikiforuken Limba Engleză Paperback – 29 apr 2014

Ancient civilizations routinely relied on shackled human muscle. It took the energy of slaves to plant crops, clothe emperors, and build cities. In the early 19th century, the slave trade became one of the most profitable enterprises on the planet. Economists described the system as necessary for progress. Slaveholders viewed religious critics as hostilely as oil companies now regard environmentalists. Yet the abolition movement that triumphed in the 1850s had an invisible ally: coal and oil. As the world's most portable and versatile workers, fossil fuels replenished slavery's ranks with combustion engines and other labor-saving tools. Since then, oil has changed the course of human life on a global scale, transforming politics, economics, science, agriculture, gender, and even our concept of happiness. But as best-selling author Andrew Nikiforuk argues in this provocative book, we still behave like slaveholders in the way we use energy, and that urgently needs to change. Cheap oil transformed the United States from a resilient republic into a global petroleum evangelical, then a sickly addict. Modern economics owes its unrealistic models to fossil fuels. On the global stage, petroleum has fueled a demographic explosion, turning 1 billion people into 7 billion in just a hundred years.

Din seria David Suzuki Institute

-

Preț: 119.79 lei

Preț: 119.79 lei -

Preț: 155.65 lei

Preț: 155.65 lei -

Preț: 199.70 lei

Preț: 199.70 lei -

Preț: 100.20 lei

Preț: 100.20 lei -

Preț: 149.92 lei

Preț: 149.92 lei -

Preț: 106.79 lei

Preț: 106.79 lei -

Preț: 102.20 lei

Preț: 102.20 lei -

Preț: 69.66 lei

Preț: 69.66 lei -

Preț: 129.74 lei

Preț: 129.74 lei -

Preț: 101.54 lei

Preț: 101.54 lei -

Preț: 88.58 lei

Preț: 88.58 lei -

Preț: 97.43 lei

Preț: 97.43 lei -

Preț: 75.45 lei

Preț: 75.45 lei -

Preț: 94.66 lei

Preț: 94.66 lei -

Preț: 130.59 lei

Preț: 130.59 lei -

Preț: 90.01 lei

Preț: 90.01 lei -

Preț: 150.18 lei

Preț: 150.18 lei -

Preț: 61.55 lei

Preț: 61.55 lei -

Preț: 163.64 lei

Preț: 163.64 lei -

Preț: 69.33 lei

Preț: 69.33 lei -

Preț: 109.10 lei

Preț: 109.10 lei -

Preț: 89.60 lei

Preț: 89.60 lei - 21%

Preț: 91.20 lei

Preț: 91.20 lei - 22%

Preț: 90.39 lei

Preț: 90.39 lei - 20%

Preț: 65.97 lei

Preț: 65.97 lei - 21%

Preț: 65.44 lei

Preț: 65.44 lei - 23%

Preț: 157.73 lei

Preț: 157.73 lei - 21%

Preț: 64.55 lei

Preț: 64.55 lei - 25%

Preț: 60.91 lei

Preț: 60.91 lei -

Preț: 122.25 lei

Preț: 122.25 lei - 21%

Preț: 37.81 lei

Preț: 37.81 lei - 21%

Preț: 119.78 lei

Preț: 119.78 lei

Preț: 66.35 lei

Preț vechi: 83.03 lei

-20% Nou

Puncte Express: 100

Preț estimativ în valută:

12.70€ • 13.26$ • 10.51£

12.70€ • 13.26$ • 10.51£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781771640107

ISBN-10: 1771640103

Pagini: 296

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: Grey Stone Books

Colecția Greystone Books

Seria David Suzuki Institute

Locul publicării:Canada

ISBN-10: 1771640103

Pagini: 296

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: Grey Stone Books

Colecția Greystone Books

Seria David Suzuki Institute

Locul publicării:Canada

Cuprins

Prologue

Chapter One: The Gods of Energy

Chapter Two: The Energy of Slaves

Chapter Three: The American Empire

Chapter Four: Petro States

Chapter Five: The Viagra of the Species

Chapter Six: The Economist's Delusion

Chapter Seven: Unsettled Farms

Chapter Eight: The Urban Explosion

Chapter Nine: Peak Science

Chapter Ten: Oil and Happiness

Chapter Eleven: Japan and the Fragility of the Petroleum Age

Epilogue

Chapter One: The Gods of Energy

Chapter Two: The Energy of Slaves

Chapter Three: The American Empire

Chapter Four: Petro States

Chapter Five: The Viagra of the Species

Chapter Six: The Economist's Delusion

Chapter Seven: Unsettled Farms

Chapter Eight: The Urban Explosion

Chapter Nine: Peak Science

Chapter Ten: Oil and Happiness

Chapter Eleven: Japan and the Fragility of the Petroleum Age

Epilogue

Recenzii

"In this cogently argued book, Andrew Nikiforuk deploys a powerful metaphor. Oil dependency, he writes, is a modern form of slavery-and it's time for a global abolition movement" —Taras Grescoe, author of Bottomfeeder

"A startling critique that should rouse us from our pipe dream of endless plenty." —Ronald Wright, author of A Short History of Progress

"Our overwhelming societal dependence on oil is usually discussed in economic terms. This book looks at our Promethean petro-prowess through an ethical lens, and the result is both shocking and deeply enlightening. This is required reading for everyone who uses oil (do you know anyone who doesn't?)." —Richard Heinberg, Senior Fellow, Post Carbon Institute, and author of The End of Growth and The Party’s Over.

Awards and praise for Empire of the Beetle:

• Nominated for the Governor General's Literary Award for Non-Fiction

• Nominated for the MPIBA Reading the West award

• Globe & Mail Top 100 Books of the Year

• amazon.ca Best Books of the Year: Non-Fiction

"Nikiforuk tallies the human and ecological costs of bark beetles' destruction of wide swathes of trees, costs that are exacerbated by climate change. His plainspoken writing style is especially poignant as he gives voice to the devastating human experience of lost forests. Recommended." —Library Journal, Oct 1, 2011

""Nikiforuk leavens this tragic, instructive history with curious facts about the complex, intelligent insect ...[his] florid language, affection for the beetles, and scorn for the humans in his story...lighten the tone of what in other hands could be an overwhelmingly depressing topic." —Publishers Weekly

"...packed with statistics, vivid descriptions of bark beetle life cycles, and portraits of scientists and forest managers struggling to cope with beetle colonies..." —Los Angeles Times

"Noted Canadian journalist Nikiforuk (Tar Sands, 2008) examines the causes and results of a series of bark beetle outbreaks starting in the late 1980s, which destroyed more than 30 billion pine and spruce trees...Well written and informative. Summing Up: Highly recommended." —CHOICE Current Reviews For Academic Libraries

"...an eye-opener, not just about how much damage bark beetles are doing but on how much humans have laid the table for the bugs' banquet." —The Commercial Dispatch, Oct 26, 2011

"Nikiforuk draws on interviews with scientists, foresters and rural residents to paint a nuanced picture of beetle outbreaks and their long-term implications." —Science News, Oct 7, 2011

""A terrific book on a terrifying subject. Andrew Nikiforuk is the first person to put this ominous New World catastrophe into such vivid context. Empire of the Beetle is a chilling, fascinating, and important contribution to our understanding of a rapidly changing world." —John Vaillant, author of The Tiger

Awards and praise for Tar Sands:

• Rachel Carson Environment Book Award, 2009

• Award of Special Merit, Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment, 2009

• Nominated for the Grantham Prize for Excellence in Reporting on the Environment, 2009

• W.O. Mitchell City of Calgary Book Award, 2009

• Shortlisted for the B.C. Booksellers' Choice Award, 2009

• Shortlisted for the CBC Libris Awards Non-Fiction Book of the Year, 2009

"Andrew Nikiforuk reveals the true costs of America's oil addiction. Tar Sands tells an important story with passion and wit." —Elizabeth Kolbert, author of Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, Nature, and Climate Change

"Read this book, be entertained, be ashamed, and then do something to stop the insanity.... This book is a slashing indictment of politicians in the back pockets of energy megacorporations, of regulators cowed into acquiescence, and of all of us who look the other way as we fill our gas tanks." —Thomas Homer-Dixon, author of The Upside of Down

"Passionate and forcefully argued, Tar Sands is a wake-up call not just to Canadians but to the wider world to take a serious look at what is happening in northern Alberta. To call this book a polemic is a compliment." —Margaret MacMillan, author of Paris 1919

"Nikiforuk offers a scathing critique of what he calls the corporate greed and regulatory indifference that have attended development of Canada's vast oil patch"-"Green Inc.," —The New York Times

Notă biografică

Andrew Nikiforuk is an award-winning Canadian journalist who has written about education, economics, and the environment for the last two decades. His books include Pandemonium; Saboteurs: Wiebo Ludwig's War against Oil, which won the Governor General's Literary Award for Nonfiction; The Fourth Horseman; and Tar Sands, which won the Rachel Carson Environment Book Award and became a national bestseller.

His most recent book, Empire of the Beetle, was nominated for the Governor General's Literary Award for Non-Fiction and selected as a top book of the year by both The Globe and Mail and Amazon. He lives in Calgary, Alberta.

His most recent book, Empire of the Beetle, was nominated for the Governor General's Literary Award for Non-Fiction and selected as a top book of the year by both The Globe and Mail and Amazon. He lives in Calgary, Alberta.

Extras

From Chapter 1:

Alfred North Whitehead, the popular English philosopher and mathematician, once wondered why the abolition of something as cruel as slavery took so long to move the human heart. Why, he asked, did it take several thousand years before an abolition movement finally emerged to break the chains in the 1850s? Why did philosophers as great as Aristotle and Seneca have no objections to fettering human muscle? In 1932 the quizzical professor offered a tentative answer: "It may be impossible to conceive a reorganization of society adequate for the removal of some admitted evil without destroying the social organization and civilization which depends on it," he concluded. Whitehead then added a caveat: "An allied plea is that there is no known way of removing the evil without the introduction of worse evils of some other type."

More than a decade ago, Donella Meadows pondered the same question. The organic gardener and lead author on Limits to Growth admitted that, yes, she was a slave owner. Although her energy helpers came with names like High Octane and Black Gold, she possessed chattel, as had Thomas Jefferson, author of the American Declaration of Independence. Her admission stunned and angered many people. What on earth was this pioneering environmental scientist thinking?

To Meadows, the admission honestly reflected how energy molds our lives: whereas Jefferson employed scores of slaves at his Virginia plantation, Meadows burned as many as 30 barrels of oil a year to get work done. Jefferson relied on enslaved human muscle, the energy system that his contemporary Thomas Paine once called "Man Stealing." Thanks to petroleum, Meadows employed invisible slaves with chains of carbon that came from ancient plants....

Before oil or coal, civilization ran on a natural two-cycle engine: the energy of solar-fed crops and the energy of slaves. Slaves built empires and nurtured civilizations from Mesopotamia to Mexico. In fact, the ancients, our practical ancestors, understood the cost and laws of energy better than most oil consumers. They knew that slaves made efficient energy converters and created healthy surpluses. With a minimum of calories provided by cereal crops, a group of organized slaves could, well, move mountains, carry a litter of rich people, build irrigation works, fight wars or simply make life easier for their masters.

As a consequence, organized human muscle powered, glorified and emboldened most empires and civilizations. Until three hundred years ago, most people viewed slavery or indentured labor as part of the natural order of things. The energy of slaves brought cheap sugar, cotton and coffee to the global marketplace. But in the 18th century the employment of coal as fuel for steam engines changed this old energy order. It fostered a remarkable transition that made the abolition of slavery not only economically possible but thinkable.

Now that North Americans have exchanged slaves for fossil fuels, we regard our new hydrocarbon servants with a similar determinism. Aristotle once wrote that animals and slaves "lend us their physical efforts to satisfy the needs of existence" and that therefore humanity was divided into two groups: "the masters and slaves." It remains such. Except the new masters, consumers, command eminently more powerful and numerous mechanical slaves powered by petroleum. To most of us, until recently, this arrangement has appeared as morally correct as did the Atlantic slave trade to 17th-century British businessmen. Petroleum's fantastic and Olympian impact on civilization can't really be appreciated without examining the energy of slaves.

In 2010, Kjell Aleklett, president of the Association for Peak Oil, visited Rome. The physicist toured the Colosseum, as many tourists do, with a measure of awe. The 70,000- seat stadium took eight years to build. Slaves (30,000 to 50,000 of them) constructed the edifice at the peak of the Empire. Each slave received two bottles of wine a day and a large meal at the end of the working day. Aleklett figures that the slaves represented energy work equal to the burning of 15 to 25 barrels of oil a day, and that it took another 60-100 barrels of oil in the form of food to keep them running. "As the empire expanded the Romans needed more slaves, and ultimately, they reached the end of the road, where they could not conquer additional nations to expand the number of slaves. In this way an energy shortage could have been the downfall of the Roman Empire."

The energy expert Vaclav Smil has made some interesting observations about Roman slavery as well. The majority of slaves toiled in the fields. A modern-day petroleum farmer in the U.S. Midwest can produce, with two hours of labour in an air-conditioned machine, a tonne of wheat. The most creative Roman farmer needed 350 hours to produce an equal volume. In a day's work, an American farmer could provide enough grain to feed 180 Romans for a month. The labour of a Roman slave or peasant could "barely supply a monthly ration for a single household slave." Smil asks two impertinent questions: Can North Americans truly support a society where every person enjoys access to roughly 50 times more useful energy (heat, motion, light) than was the Roman norm? Could a Roman citizen have conceived of living in a society where every person was attended in power terms by an equivalent of 50 strong and continuously hard-working slaves?

...

The Atlantic slave trade peaked in the 1700s and thereafter experienced numerous political shocks in the form of insurrections and rebellions. One famous revolt lead by Toussaint L'Ouverture, a brilliant New World Spartacus, eventually defeated a British army of 40,000 men in Haiti. It was the only successful slave revolt on historical record. Nevertheless, rebellions and runaways increasingly challenged the economics of plantation economies throughout the West Indies in the 18th century.

But the wider abolition movement was a child of western Europe. "In no non-western countries did abolition emerge independently as official state policy, and no non-western intellectual tradition showed signs of questioning slavery per se," notes slave trade historian David Eltis. The reasons all point to England's industrial revolution.

England didn't pioneer coal burning for heat, but it did industrialize its use in the 17th century. Having cut down most of their forests for fuel, the British faced a genuine wood scarcity, and so turned to coal as a substitute. Demand grew quickly, and by the 18th century coal miners constituted a singular and rough class of men employed in dangerous work. The British mostly regarded miners with the same contempt that Romans reserved for slaves. But when water started to flood deep coal-mines and drown miners, early engineers resorted to buckets, hand pumps and horses. Horses cost lots of money to feed, and so the nation looked for cheaper pumps. Ironmonger Thomas Newcomen fashioned a one-piston device known as a "fire engine." James Watt, a quiet Scottish mechanic, tinkered and improved the design for Newcomen's mechanical pump and vastly improved its efficiency. His refined model for the steam engine appeared in 1782. Thomas Clarkson, the anti-slavery leader Samuel Coleridge called a "moral steam engine," began his campaign just five years later.