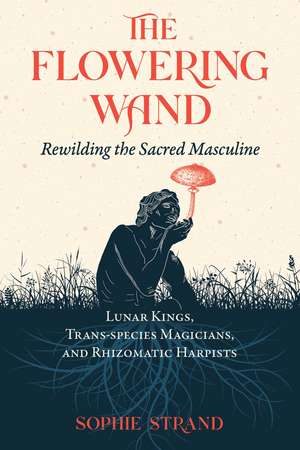

The Flowering Wand: Rewilding the Sacred Masculine

Autor Sophie Stranden Limba Engleză Paperback – 22 dec 2022

• Reveals the restorative fungi archetype of Osiris, the Orphic mysteries as an underground mycelium linking forests and people, how Dionysus teaches us about invasive species and playful sexuality, and the ecology of Jesus as depicted in his nature-focused parables

• Liberates Tristan, Merlin, and the Grail legends from the bounds of Campbell’s hero’s journey and invites the masculine into more nuanced, complex ways of dealing with trauma, growth, and self-knowledge

Long before the sword-wielding heroes of legend readily cut down forests, slaughtered the old deities, and vanquished their enemies, there were playful gods, animal-headed kings, mischievous lovers, trickster harpists, and vegetal magicians with flowering wands. As eco-feminist scholar Sophie Strand discovered, these wilder, more magical modes of the masculine have always been hidden in plain sight.

Sharing the culmination of eight years of research into myth, folklore, and the history of religion, Strand leads us back into the forgotten landscapes and hidden secrets of familiar myths, revealing the beautiful range of the divine masculine, including expressions of male friendship, male intimacy, and male creative collaboration. In discussing Dionysus and Osiris, Strand encourages us to think like an ecosystem instead of like an individual. She connects dying, vegetal gods to the virtuous cycle of composting and decay, highlighting the ways in which mushrooms can restore soil and heal polluted landscapes. Exploring esoteric Christianity, the author celebrates the Gnostic Jesus of the Gospel of Thomas, imagining the ecology that the Rabbi Yeshua would have actually been referencing in his nature-focused parables. Strand frees Tristan, Merlin, and the Grail legends from the bounds of Campbell’s hero’s journey and invites the masculine into more nuanced, complex ways of dealing with trauma, growth, and self-knowledge.

Strand reseeds our minds with new visions of male identity and shows how each of us, regardless of gender, can develop a matured ecological empathy and witness a blossoming of sacred masculine powers that are soft, curious, connective, and celebratory.

Preț: 76.93 lei

Preț vechi: 102.35 lei

-25% Nou

Puncte Express: 115

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.72€ • 15.41$ • 12.18£

14.72€ • 15.41$ • 12.18£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 21 martie-02 aprilie

Livrare express 28 februarie-06 martie pentru 49.100 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781644115961

ISBN-10: 1644115964

Pagini: 208

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.35 kg

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Inner Traditions

ISBN-10: 1644115964

Pagini: 208

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.35 kg

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Inner Traditions

Notă biografică

Sophie Strand is a poet and writer with a focus on the history of religion and the intersection of spirituality, storytelling, and ecology. Her poems and essays have appeared in numerous projects and publications, including the Dark Mountain Project and poetry.org and the magazines Unearthed, Braided Way, Art PAPERS, and Entropy. She lives in the Hudson Valley of New York.

Extras

Chapter 4

The Minotaur Dances the Masculine Back into the Milky Way

The story goes that King Minos of Crete disobeyed the gods by refusing to sacrifice a sacred bull. In retribution, the god Poseidon caused Minos’s wife, Pasiphae, to become enamored of the bull, and she then copulated with it, producing a monstrous horned child. Little is said of the Minotaur’s misdoings, but he is nevertheless deemed dangerous, or at least hideous enough, that he must be sequestered away in a labyrinth that can be neither easily navigated nor exited.

Young Theseus of Athens comes to the rescue, wooing the Minotaur’s sister, Ariadne, so that she reveals the secrets of the labyrinth. The patriarchal hero slays the Minotaur, wins the heart of the Cretan princess, and sets sail for more adventures, discarding Ariadne on another island almost as quickly as he had claimed her.

Theseus sets the template for heroic action: the knight or warrior who slays the dragon, the monster, the Gorgon. The hero contextualizes his valor, his purpose, by pushing against and defeating the adversary. But who is the adversary? Is it really a monster? What if I told you there was a secret inside every dragon-slaying, beast-destroying myth you’ve ever heard? And what if that secret was both tender and tragic? What if behind every famous monster there was a mother? When I say mother, I do not literally mean a singular human mother or even a female. Mother indicates a matriarchal, nature-based cosmology. An earth-reverent, land-based way of being that is murdered and subsumed into a “solarized” sun god pantheon.

Let us start with the basics. “And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters,” begins Genesis, a text scholars agree was probably compiled during the Babylonian exile and influenced by the surrounding Sumerian mythologies. In the Hebrew Bible, deep— from “the face of the deep”—is Tehom. As scholar A. E. Whatham points out, for Babylonian captives, Tehom would have had a very different resonance than just “deep.” They would have known that Tehom of Genesis is directly tied to Tiamat, the mother sea goddess of Babylonian creation myths.1

In her earliest incarnations, Tiamat was revered as a symbol of the primordial sea that gave rise to all of creation. However, though Babylonian religion is on a rhizomatic continuity with Sumerian religion, the acts of translation between the cosmologies were not peaceful. Tiamat came to be seen as a giant, menacing snake or dragon. She serves as one of the most painful and clearest examples of a mother transformed into a monster, narratively justifying her murder.

The transformation of Bronze Age mother-goddess cultures, or partnership societies, as Riane Eisler calls them in The Chalice and the Blade, began with the violent influx of Indo-Germanic tribes into the Mediterranean, decimating existing populations. Joseph Campbell, among others, characterized the resulting cultural shift as a subjugation of lunar goddess devotion by solarized hero worship.2 In other words, nature reverence turned into nature domination.

The most well-known myth about Tiamat, the Enuma Elish, characterizes the mother sea goddess as hideous. She has a tail. Udders. She is huge. She is dangerously powerful. Her grandson, Marduk, called the “solar calf,” is envious of her power, fears her ability to give birth to inhuman deities and monsters, and destroys her in the most obscene way possible, exploding her body, ripping her apart. The Babylonian images of this battle that survive show the direct line between Marduk slaying Tiamat and the later legends of Saint George and the dragon. In similar fashion, the earlier mother religions of the underworld goddess Inanna, the sea goddess Nammu, and the other Neolithic madonnas of vegetal regeneration and birth sink into the water below the glaring solar eye of the new sky gods and their pantheon of heroes.

The mythology of the sacred bull and the labyrinth far predate Greek myths. According to the research of acclaimed mythologist Carl Kerényi and writings of scholar Anne Baring, these stories go back to the Neolithic pre-palatial period of Crete (7000 to 1900 BCE), before the Greek invasion and fall of Minoan culture in 1775 BCE.3

I’ll offer that the mythology of sacred bulls is even older than that. Images of bulls can be seen in the twenty-thousand-year-old cave paintings in Lascaux, France. From 4000 to 3500 BCE, as Joseph Campbell charts in his book Occidental Mythology, cattle cults swept across Mesopotamia, creating what he asserts is a dominant preHomeric, pre-Olympic pantheon of lunar bull gods and underworld goddesses. Ceremonial horns and bull heads have been unearthed in many Neolithic and early Bronze Age settlements, including the protocities Çatalhöyük and Harappa. More recently, the Egyptians worshipped a bull version of the god Osiris, called Apis, and also revered sacred horns and bull heads.

When we look at Greek myths—chock-full of monsters, rape, pillage, and heroic valor—we have to remember that many of these myths are translations of older stories, or at least fusions of two competing mythologies: one focused on nature reverence and mother goddesses, and the other characterized by violent heroes and a “solarization” of gods and sacred symbols. The lunar realm of the labyrinth lies, palimpsest-like, under the sunlit girth of Mount Olympus, flickering in and out of the Greek pantheon. It didn’t disappear when the Indo-Germanic tribes subjugated the earlier Mediterranean populations. But, deracinated and replanted into a new, violent mythological ecosystem, earlier gods became murderous monsters, and goddesses withered into helpless princesses.

Let us look again at the Minotaur myth. And let us look closely at what archaeologists and historians have managed to reconstruct about life on Crete, a culture that Riane Eisler asserts was the healthy precursor to patriarchy. “One of the most striking things about Neolithic art is what it does not depict,” she observes. “For what a people do not depict in their art can tell us as much about them as what they do.”4 Prior to the fall of Minoan culture, Crete had no fortified walls. Most importantly, there are no known depictions of violence or war in its extensive offering of art.

Instead, nature in all its wild fecundity is depicted in frescoes, mosaics, drinking vessels, statues, and seals. Spirals, snake-evocative chevrons, vegetation, and animals dominate the imagery. Women conduct rituals bare-breasted. Goddesses are flanked by lions. The few times that men appear, they are shown most often in positions suggesting awe and reverence, lifting their arms to a goddess or animal. Death is not depicted; neither is suffering. Physical pleasure, bulls, lunar reverence, communion with nature, and feminine divinity are prevalent. But I sense that the dominant theme here is not an object but the fluid connectivity between these symbols. Minoan culture—the origin of the Minotaur—is characterized by movement, by dance itself.

Cretan scholar Nikolaos Platon, in his Guide to the Archeological Museum of Heraclion, muses about Minoan culture: “Motion is its ruling characteristic; the figures move with lovely grace, the decorative designs whirl and turn, and even the architectural composition is allied to incessant movement become multiform and complex.” Nowhere is this better displayed than in the many images of the “bull dance,” in which young Cretan women and men appear to leap and play with bulls. Some have speculated that this is part of a ritual sacrifice, ending with the slaying of the bull as a surrogate for a lunar king. Others postulate that the dancers themselves were the sacrifice, gored by the bull’s lethal horns. But nowhere in the imagery is there blood or death. What we have is dance. Cretan culture is essentially kinetic. Divinity is reached not through heroic individualism but through connective, dynamic play. God does not dwell in the leaping youth or the charging bull but is constituted interstitially between the moving figures. The dance itself is the divine.

The Minotaur, then, is a dancer. His horns, like those of the sacred bull, echoed the shape of the crescent moon and the lunar rhythms that welcome both light and dark. The Minotaur was the god of mutability and movement. He represented the fluid, pleasureful interface between human beings and the animate world of everything else.

When Theseus slays the Minotaur, he is not slaying a monster. He is slaying an entire culture—a Cretan culture dominated by the image of a feminine divinity, flanked by lions and bulls, celebrating epiphanic communion with the natural world.

In the same way, Apollo, god of order and sterility and reason, god of the left brain, kills Python, the serpent who presided over the Oracle at Delphi, son of the mother earth goddess Gaia. Snakes are traditionally symbols of the goddess.5 They are literally close to the earth, pressing their whole kinetic, shivering life force against her. In mythology, we can see the slaying or denigration of a snake as a nod to the destruction of partnership societies, nature worship, and goddess devotion.

Perseus likewise kills the snake goddess Medusa. Both Robert Graves and Joseph Campbell thought it was quite likely that the Perseus legend references the thirteenth-century BCE invasion of the Hellenes (Aryans/Greeks), who overran the goddess’s chief shrines in the Mediterranean basin.6

The myth of Saint George slaying the dragon is a direct overlay of Christianity’s thousands-of-years-long attempt to erase animist pagan European traditions. Who is the dragon? It could be Ireland’s Cailleach or Morrigan. It could be the millions of women, femmes, and queer people who were murdered during the Inquisition for their pagan spiritual practices.

Who is the monster of today’s legends? Today, we see a surfeit of media coverage devoted to weather and climate events. Has the biosphere become the monster? Every attempt to create weather- or climate-regulating technology, rather than adjusting and halting our own abysmal behaviors, posits Earth as a monster and humankind as the “heroes” who must control her and tame her and save her. Technonarcissists are the new Marduk. The new Theseus. They want the myth of progress to subsume the older (although newly investigated in the realms of quantum physics and glacial ice coring) chaos of emergent systems and biospheric intelligence. Earth doesn’t know best, our cultures insist. We know best. And we must progress ever onward toward greater control.

Before his Greek bastardization into an anonymous monster, the Minotaur had a name: Asterion, or “starry one.” His name may have referred to the constellation Taurus or to the rising of Sirius, an event that is correlated to Cretan festivals and sacred mead making.7 So when we think of the Minotaur in the labyrinth, perhaps we are really seeing a solar system. The Minotaur is the guiding star. The labyrinth’s winding courses are the paths of planets, objects, beings, galactic dust, caught in the divine pull of a horned nucleus.

And every star must have its Ariadne, whom we can resurrect from her defeated position in Theseus’s mythology. The Linear B tablets found at the Cretan palace of Knossos read, “. . . and for the lady of the labyrinth, a jar of honey.”8 This offering shows us that the lady associated with the labyrinth is sacred, honored by a gift of wild sweetness. In The Myth of the Goddess, Anne Baring and Jules Cashford point out the preponderance of bulls in the myth: Passiphae’s bull, the Minotaur, the bull-associated god Poseidon, and finally the savior of Ariadne, the horned bull god Dionysus, who rescues her from exile on the island of Naxos. Reading the images, we can consolidate all the bulls into one nucleus at the center of the labyrinth. The Minotaur is no longer the betrayed brother of Ariadne. He is Asterion, her partner in sacred movement: that of the swarming bees in the hive, dancing while they make Ariadne’s ritual honey, and that of the dance of the bull with his human partners, leaping and rolling and charging.

Despite the preponderance of labyrinth myths and images, no remains of a labyrinth have ever been located in Crete. I want to offer another interpretation: The labyrinth was never a static object or a place. It was never a stone corridor. Instead, it was an event. It was a ritual dance to honor the bull and the annual rising of certain constellations. Each “passageway” was a chain of human hands, a serpentine gyration of gestures. The labyrinth was only ever the sacred relationship between people dancing—ecstatically, kinetically—inscribing the patterns of the sky into the soft dirt of the ground.

If the Minotaur offers the masculine anything, it is the healing power of playful, expressive movement. The kind of movement that understands it is always in dialogue with other animals, the weather, the texture and slope of the landscape between our toes. Let the masculine learn how to dance again. And like the starry Asterion, the more we dance, the more people will be attracted into our orbit of participatory, exultant celebration.

Finally, let the Minotaur stand as a reminder: There are no monsters. Only bad rewrites of forgotten stories.

The Minotaur Dances the Masculine Back into the Milky Way

The story goes that King Minos of Crete disobeyed the gods by refusing to sacrifice a sacred bull. In retribution, the god Poseidon caused Minos’s wife, Pasiphae, to become enamored of the bull, and she then copulated with it, producing a monstrous horned child. Little is said of the Minotaur’s misdoings, but he is nevertheless deemed dangerous, or at least hideous enough, that he must be sequestered away in a labyrinth that can be neither easily navigated nor exited.

Young Theseus of Athens comes to the rescue, wooing the Minotaur’s sister, Ariadne, so that she reveals the secrets of the labyrinth. The patriarchal hero slays the Minotaur, wins the heart of the Cretan princess, and sets sail for more adventures, discarding Ariadne on another island almost as quickly as he had claimed her.

Theseus sets the template for heroic action: the knight or warrior who slays the dragon, the monster, the Gorgon. The hero contextualizes his valor, his purpose, by pushing against and defeating the adversary. But who is the adversary? Is it really a monster? What if I told you there was a secret inside every dragon-slaying, beast-destroying myth you’ve ever heard? And what if that secret was both tender and tragic? What if behind every famous monster there was a mother? When I say mother, I do not literally mean a singular human mother or even a female. Mother indicates a matriarchal, nature-based cosmology. An earth-reverent, land-based way of being that is murdered and subsumed into a “solarized” sun god pantheon.

Let us start with the basics. “And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters,” begins Genesis, a text scholars agree was probably compiled during the Babylonian exile and influenced by the surrounding Sumerian mythologies. In the Hebrew Bible, deep— from “the face of the deep”—is Tehom. As scholar A. E. Whatham points out, for Babylonian captives, Tehom would have had a very different resonance than just “deep.” They would have known that Tehom of Genesis is directly tied to Tiamat, the mother sea goddess of Babylonian creation myths.1

In her earliest incarnations, Tiamat was revered as a symbol of the primordial sea that gave rise to all of creation. However, though Babylonian religion is on a rhizomatic continuity with Sumerian religion, the acts of translation between the cosmologies were not peaceful. Tiamat came to be seen as a giant, menacing snake or dragon. She serves as one of the most painful and clearest examples of a mother transformed into a monster, narratively justifying her murder.

The transformation of Bronze Age mother-goddess cultures, or partnership societies, as Riane Eisler calls them in The Chalice and the Blade, began with the violent influx of Indo-Germanic tribes into the Mediterranean, decimating existing populations. Joseph Campbell, among others, characterized the resulting cultural shift as a subjugation of lunar goddess devotion by solarized hero worship.2 In other words, nature reverence turned into nature domination.

The most well-known myth about Tiamat, the Enuma Elish, characterizes the mother sea goddess as hideous. She has a tail. Udders. She is huge. She is dangerously powerful. Her grandson, Marduk, called the “solar calf,” is envious of her power, fears her ability to give birth to inhuman deities and monsters, and destroys her in the most obscene way possible, exploding her body, ripping her apart. The Babylonian images of this battle that survive show the direct line between Marduk slaying Tiamat and the later legends of Saint George and the dragon. In similar fashion, the earlier mother religions of the underworld goddess Inanna, the sea goddess Nammu, and the other Neolithic madonnas of vegetal regeneration and birth sink into the water below the glaring solar eye of the new sky gods and their pantheon of heroes.

The mythology of the sacred bull and the labyrinth far predate Greek myths. According to the research of acclaimed mythologist Carl Kerényi and writings of scholar Anne Baring, these stories go back to the Neolithic pre-palatial period of Crete (7000 to 1900 BCE), before the Greek invasion and fall of Minoan culture in 1775 BCE.3

I’ll offer that the mythology of sacred bulls is even older than that. Images of bulls can be seen in the twenty-thousand-year-old cave paintings in Lascaux, France. From 4000 to 3500 BCE, as Joseph Campbell charts in his book Occidental Mythology, cattle cults swept across Mesopotamia, creating what he asserts is a dominant preHomeric, pre-Olympic pantheon of lunar bull gods and underworld goddesses. Ceremonial horns and bull heads have been unearthed in many Neolithic and early Bronze Age settlements, including the protocities Çatalhöyük and Harappa. More recently, the Egyptians worshipped a bull version of the god Osiris, called Apis, and also revered sacred horns and bull heads.

When we look at Greek myths—chock-full of monsters, rape, pillage, and heroic valor—we have to remember that many of these myths are translations of older stories, or at least fusions of two competing mythologies: one focused on nature reverence and mother goddesses, and the other characterized by violent heroes and a “solarization” of gods and sacred symbols. The lunar realm of the labyrinth lies, palimpsest-like, under the sunlit girth of Mount Olympus, flickering in and out of the Greek pantheon. It didn’t disappear when the Indo-Germanic tribes subjugated the earlier Mediterranean populations. But, deracinated and replanted into a new, violent mythological ecosystem, earlier gods became murderous monsters, and goddesses withered into helpless princesses.

Let us look again at the Minotaur myth. And let us look closely at what archaeologists and historians have managed to reconstruct about life on Crete, a culture that Riane Eisler asserts was the healthy precursor to patriarchy. “One of the most striking things about Neolithic art is what it does not depict,” she observes. “For what a people do not depict in their art can tell us as much about them as what they do.”4 Prior to the fall of Minoan culture, Crete had no fortified walls. Most importantly, there are no known depictions of violence or war in its extensive offering of art.

Instead, nature in all its wild fecundity is depicted in frescoes, mosaics, drinking vessels, statues, and seals. Spirals, snake-evocative chevrons, vegetation, and animals dominate the imagery. Women conduct rituals bare-breasted. Goddesses are flanked by lions. The few times that men appear, they are shown most often in positions suggesting awe and reverence, lifting their arms to a goddess or animal. Death is not depicted; neither is suffering. Physical pleasure, bulls, lunar reverence, communion with nature, and feminine divinity are prevalent. But I sense that the dominant theme here is not an object but the fluid connectivity between these symbols. Minoan culture—the origin of the Minotaur—is characterized by movement, by dance itself.

Cretan scholar Nikolaos Platon, in his Guide to the Archeological Museum of Heraclion, muses about Minoan culture: “Motion is its ruling characteristic; the figures move with lovely grace, the decorative designs whirl and turn, and even the architectural composition is allied to incessant movement become multiform and complex.” Nowhere is this better displayed than in the many images of the “bull dance,” in which young Cretan women and men appear to leap and play with bulls. Some have speculated that this is part of a ritual sacrifice, ending with the slaying of the bull as a surrogate for a lunar king. Others postulate that the dancers themselves were the sacrifice, gored by the bull’s lethal horns. But nowhere in the imagery is there blood or death. What we have is dance. Cretan culture is essentially kinetic. Divinity is reached not through heroic individualism but through connective, dynamic play. God does not dwell in the leaping youth or the charging bull but is constituted interstitially between the moving figures. The dance itself is the divine.

The Minotaur, then, is a dancer. His horns, like those of the sacred bull, echoed the shape of the crescent moon and the lunar rhythms that welcome both light and dark. The Minotaur was the god of mutability and movement. He represented the fluid, pleasureful interface between human beings and the animate world of everything else.

When Theseus slays the Minotaur, he is not slaying a monster. He is slaying an entire culture—a Cretan culture dominated by the image of a feminine divinity, flanked by lions and bulls, celebrating epiphanic communion with the natural world.

In the same way, Apollo, god of order and sterility and reason, god of the left brain, kills Python, the serpent who presided over the Oracle at Delphi, son of the mother earth goddess Gaia. Snakes are traditionally symbols of the goddess.5 They are literally close to the earth, pressing their whole kinetic, shivering life force against her. In mythology, we can see the slaying or denigration of a snake as a nod to the destruction of partnership societies, nature worship, and goddess devotion.

Perseus likewise kills the snake goddess Medusa. Both Robert Graves and Joseph Campbell thought it was quite likely that the Perseus legend references the thirteenth-century BCE invasion of the Hellenes (Aryans/Greeks), who overran the goddess’s chief shrines in the Mediterranean basin.6

The myth of Saint George slaying the dragon is a direct overlay of Christianity’s thousands-of-years-long attempt to erase animist pagan European traditions. Who is the dragon? It could be Ireland’s Cailleach or Morrigan. It could be the millions of women, femmes, and queer people who were murdered during the Inquisition for their pagan spiritual practices.

Who is the monster of today’s legends? Today, we see a surfeit of media coverage devoted to weather and climate events. Has the biosphere become the monster? Every attempt to create weather- or climate-regulating technology, rather than adjusting and halting our own abysmal behaviors, posits Earth as a monster and humankind as the “heroes” who must control her and tame her and save her. Technonarcissists are the new Marduk. The new Theseus. They want the myth of progress to subsume the older (although newly investigated in the realms of quantum physics and glacial ice coring) chaos of emergent systems and biospheric intelligence. Earth doesn’t know best, our cultures insist. We know best. And we must progress ever onward toward greater control.

Before his Greek bastardization into an anonymous monster, the Minotaur had a name: Asterion, or “starry one.” His name may have referred to the constellation Taurus or to the rising of Sirius, an event that is correlated to Cretan festivals and sacred mead making.7 So when we think of the Minotaur in the labyrinth, perhaps we are really seeing a solar system. The Minotaur is the guiding star. The labyrinth’s winding courses are the paths of planets, objects, beings, galactic dust, caught in the divine pull of a horned nucleus.

And every star must have its Ariadne, whom we can resurrect from her defeated position in Theseus’s mythology. The Linear B tablets found at the Cretan palace of Knossos read, “. . . and for the lady of the labyrinth, a jar of honey.”8 This offering shows us that the lady associated with the labyrinth is sacred, honored by a gift of wild sweetness. In The Myth of the Goddess, Anne Baring and Jules Cashford point out the preponderance of bulls in the myth: Passiphae’s bull, the Minotaur, the bull-associated god Poseidon, and finally the savior of Ariadne, the horned bull god Dionysus, who rescues her from exile on the island of Naxos. Reading the images, we can consolidate all the bulls into one nucleus at the center of the labyrinth. The Minotaur is no longer the betrayed brother of Ariadne. He is Asterion, her partner in sacred movement: that of the swarming bees in the hive, dancing while they make Ariadne’s ritual honey, and that of the dance of the bull with his human partners, leaping and rolling and charging.

Despite the preponderance of labyrinth myths and images, no remains of a labyrinth have ever been located in Crete. I want to offer another interpretation: The labyrinth was never a static object or a place. It was never a stone corridor. Instead, it was an event. It was a ritual dance to honor the bull and the annual rising of certain constellations. Each “passageway” was a chain of human hands, a serpentine gyration of gestures. The labyrinth was only ever the sacred relationship between people dancing—ecstatically, kinetically—inscribing the patterns of the sky into the soft dirt of the ground.

If the Minotaur offers the masculine anything, it is the healing power of playful, expressive movement. The kind of movement that understands it is always in dialogue with other animals, the weather, the texture and slope of the landscape between our toes. Let the masculine learn how to dance again. And like the starry Asterion, the more we dance, the more people will be attracted into our orbit of participatory, exultant celebration.

Finally, let the Minotaur stand as a reminder: There are no monsters. Only bad rewrites of forgotten stories.

Cuprins

Introduction

The Sword or the Wand

PART 1

Back to the Roots

1 Sky, Storm, and Spore

Where Do Gods Come From?

2 The Hanged Man Is the Rooted One

Thinking from the Feet

3 Between Naming and the Unknown

Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night

4 The Minotaur Dances the Masculine Back into the Milky Way

Myths Need to Move

5 The Moon Belongs to Everyone

Lunar Medicine for the Masculine

6 Becoming a Home

The Empress Card Embraces the Masculine

7 Dionysus

Girl-Faced God of the Swarm, the Hive, the Vine, and the Emergent Mind

8 Merlin Makes Kin to Make Kingdoms

A Multiplicity of Minds and Myths

9 Joseph, Secret Vegetalista of Genesis

Plants Use Men to Dream

10 Actaeon Is the King of the Beasts

From Curse to Crown

11 A New Myth for Narcissus

Seeing Ourselves in the Ecosystem

12 Everyone Is Orpheus

Singing for Other Species

13 Dionysus as Liber

The Vine Is the Tool of the Oppressed

14 Rewilding the Beloved

Dionysus Offers New Modes of Romance

15 Grow Back Your Horns

The Devil Card Is Dionysus

PART II

Healing the Wound

16 Let Your Wings Dry

Giving the Star Card to the Masculine

17 Tristan and Transformation

Escaping the Trauma of the Hero’s Journey

18 Boy David, Wild David, King David

The Land-Based Origin of Biblical Kingship

19 Coppice the Hero’s Journey

Creating Narrative Ecosystems

20 Merlin and Vortigern

Magical Boyhood Topples Patriarchy

21 Parzifal and the Fisher King

The Grail Overflows with Stories

22 Sleeping Beauty, Sleeping World

The Prince Offers the Masculine a New Quest

23 Melt the Sacred Masculine and the Divine Feminine into Divine Animacy

The Sacred Overflows the Human

24 Resurrect the Bridegroom

The Song of Songs and Ecology as Courtship

25 Osiris

The Original Green Man

26 What’s the Matter?

A Mycelial Interpretation of the Gospel of Mary Magdalene

27 Knock upon Yourself

The High Priestess Wakes Up the Masculine

28 The Kingdom of Astonishment

Gnostic Jesus and the Transformative Power of Awe

29 Healing the Healer

Dionysus Rewilds Jesus

30 Making Amends to Attis and Adonis

No Gods Were Killed in the Making of This Myth

31 The Joyful Rescue

Tolkien’s Eucatastrophe and the Anthropocene

32 Sharing the Meal

Tom Bombadil Offers the Masculine Safe Haven

33 The Gardeners and the Seeds

Healing the Easter Wound

Conclusion

A Cure for Narrative Dysbiosis

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Index

The Sword or the Wand

PART 1

Back to the Roots

1 Sky, Storm, and Spore

Where Do Gods Come From?

2 The Hanged Man Is the Rooted One

Thinking from the Feet

3 Between Naming and the Unknown

Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night

4 The Minotaur Dances the Masculine Back into the Milky Way

Myths Need to Move

5 The Moon Belongs to Everyone

Lunar Medicine for the Masculine

6 Becoming a Home

The Empress Card Embraces the Masculine

7 Dionysus

Girl-Faced God of the Swarm, the Hive, the Vine, and the Emergent Mind

8 Merlin Makes Kin to Make Kingdoms

A Multiplicity of Minds and Myths

9 Joseph, Secret Vegetalista of Genesis

Plants Use Men to Dream

10 Actaeon Is the King of the Beasts

From Curse to Crown

11 A New Myth for Narcissus

Seeing Ourselves in the Ecosystem

12 Everyone Is Orpheus

Singing for Other Species

13 Dionysus as Liber

The Vine Is the Tool of the Oppressed

14 Rewilding the Beloved

Dionysus Offers New Modes of Romance

15 Grow Back Your Horns

The Devil Card Is Dionysus

PART II

Healing the Wound

16 Let Your Wings Dry

Giving the Star Card to the Masculine

17 Tristan and Transformation

Escaping the Trauma of the Hero’s Journey

18 Boy David, Wild David, King David

The Land-Based Origin of Biblical Kingship

19 Coppice the Hero’s Journey

Creating Narrative Ecosystems

20 Merlin and Vortigern

Magical Boyhood Topples Patriarchy

21 Parzifal and the Fisher King

The Grail Overflows with Stories

22 Sleeping Beauty, Sleeping World

The Prince Offers the Masculine a New Quest

23 Melt the Sacred Masculine and the Divine Feminine into Divine Animacy

The Sacred Overflows the Human

24 Resurrect the Bridegroom

The Song of Songs and Ecology as Courtship

25 Osiris

The Original Green Man

26 What’s the Matter?

A Mycelial Interpretation of the Gospel of Mary Magdalene

27 Knock upon Yourself

The High Priestess Wakes Up the Masculine

28 The Kingdom of Astonishment

Gnostic Jesus and the Transformative Power of Awe

29 Healing the Healer

Dionysus Rewilds Jesus

30 Making Amends to Attis and Adonis

No Gods Were Killed in the Making of This Myth

31 The Joyful Rescue

Tolkien’s Eucatastrophe and the Anthropocene

32 Sharing the Meal

Tom Bombadil Offers the Masculine Safe Haven

33 The Gardeners and the Seeds

Healing the Easter Wound

Conclusion

A Cure for Narrative Dysbiosis

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Recenzii

“If we want to locate the underlying source of our civilization’s headlong rush to destruction, we must dig deeper than capitalism, deeper even than the Western worldview, until we encounter the bedrock of patriarchy. In this exuberant tableau of resurrection, Strand reveals how even our most archetypal myths have been molded and devitalized to fit the patriarchal straitjacket, and Strand lays the groundwork for a regenerated masculinity--one that is liberated to explore life-affirming possibilities grounded in the deep wisdom of long-buried ancient lore.”

“Sophie Strand’s beautiful and poetic book is a game changer. With The Flowering Wand as a tool, it is possible to rewrite the mostly traumatizing patriarchal narratives Western males so often base their identity in and reconnect them with the underlying story of a cultural and natural deep history of mutual transformation with other beings beyond all modern binaries.”

“Sophie Strand writes with the urgency of a prophet and the musicality of a bard. Weaving myth together with botany, history with theology, her virtuosic linguistic skeins would do her beloved mycorrhizae proud. In The Flowering Wand, the masculine appears as lover, as partner, as inspirer, as friend. This is a book important in its joy, powerful in its love--exuberant in its curiosity. Taking us by the hand, Strand leads us into a garden of delights: tarot cards, ancient scriptures, Shakespearean comedies, sky gods, the Minotaur, the Milky Way. Strand holds the gates of wonder open and love comes flowing out. These are the birth waters breaking. Rejoice! The masculine is reborn.”

“A magnificent weave of ecology and myth--it is evident there’s some pretty rich dirt, culturally speaking as well as actual dirt no doubt, under the fingernails that have written this lyrical journey. A book filled with magical insight, revealing Strand’s wondrous curiosity and impressive learnings of the complex relationships between humans and nature.”

“The wisdom in this book is almost beyond expression. Sophie Strand’s The Flowering Wand reveals the full potency and profligacy of myth.”

“Sophie Strand’s work is a must-read for lovers of mythology and the Earth. Her work is poetic yet practical. It’s whimsical and transportive, yet it’s describing the world around you, inviting you back home to the reality of this mystical life and world we inhabit.”

“The Flowering Wand is a ‘wild thing’ and seeks out other forms of recombination and transformative fusion and gives them life. The surprising conclusion is, we humans have always been more-than-human. Are you wild enough to find out why?”

“Sophie Strand’s new book offers a luminous exploration of the radical mythic underpinning of the masculine narrative. Here the autocratic sky gods and sword-wielding dominators of people and landscapes are replaced by a dynamic ensemble of dancers, lovers, and liberators. Strand reminds us how these actors--from the Minotaur to Merlin--inspire people of all places and genders to break out of the straitjacket of patriarchal control and become more embodied, protean, dramaturgical, and emergent in our lives. Get entangled!”

“Sophie Strand’s words embody both the chthonic depth of well-myceliated soil and the crystals, sharp with insight, among its hyphae. In The Flowering Wand, Sophie remediates the ground of western culture by rerooting the divine masculine--in all its fertility, magic and imagination-- back into the earth. Through Sophie‘s richly seeded prose and deep scholarship she shows us how reclaiming this fertile, soporific energy--an energy that lives within us all--can help heal our connection with the Animate Everything and nourish the re-flowering of the world.”

“Readers will feel the words in this book tendril around their hearts and minds, forming adaptive connections and creating conversations with the ‘Animate Everything’ in the wilds of their everyday worlds. Myths that stay the same don’t survive, Strand tells us; she waves a wand toward the earth and summons up vital wisdom for our time.”

“Sophie Strand’s beautiful and poetic book is a game changer. With The Flowering Wand as a tool, it is possible to rewrite the mostly traumatizing patriarchal narratives Western males so often base their identity in and reconnect them with the underlying story of a cultural and natural deep history of mutual transformation with other beings beyond all modern binaries.”

“Sophie Strand writes with the urgency of a prophet and the musicality of a bard. Weaving myth together with botany, history with theology, her virtuosic linguistic skeins would do her beloved mycorrhizae proud. In The Flowering Wand, the masculine appears as lover, as partner, as inspirer, as friend. This is a book important in its joy, powerful in its love--exuberant in its curiosity. Taking us by the hand, Strand leads us into a garden of delights: tarot cards, ancient scriptures, Shakespearean comedies, sky gods, the Minotaur, the Milky Way. Strand holds the gates of wonder open and love comes flowing out. These are the birth waters breaking. Rejoice! The masculine is reborn.”

“A magnificent weave of ecology and myth--it is evident there’s some pretty rich dirt, culturally speaking as well as actual dirt no doubt, under the fingernails that have written this lyrical journey. A book filled with magical insight, revealing Strand’s wondrous curiosity and impressive learnings of the complex relationships between humans and nature.”

“The wisdom in this book is almost beyond expression. Sophie Strand’s The Flowering Wand reveals the full potency and profligacy of myth.”

“Sophie Strand’s work is a must-read for lovers of mythology and the Earth. Her work is poetic yet practical. It’s whimsical and transportive, yet it’s describing the world around you, inviting you back home to the reality of this mystical life and world we inhabit.”

“The Flowering Wand is a ‘wild thing’ and seeks out other forms of recombination and transformative fusion and gives them life. The surprising conclusion is, we humans have always been more-than-human. Are you wild enough to find out why?”

“Sophie Strand’s new book offers a luminous exploration of the radical mythic underpinning of the masculine narrative. Here the autocratic sky gods and sword-wielding dominators of people and landscapes are replaced by a dynamic ensemble of dancers, lovers, and liberators. Strand reminds us how these actors--from the Minotaur to Merlin--inspire people of all places and genders to break out of the straitjacket of patriarchal control and become more embodied, protean, dramaturgical, and emergent in our lives. Get entangled!”

“Sophie Strand’s words embody both the chthonic depth of well-myceliated soil and the crystals, sharp with insight, among its hyphae. In The Flowering Wand, Sophie remediates the ground of western culture by rerooting the divine masculine--in all its fertility, magic and imagination-- back into the earth. Through Sophie‘s richly seeded prose and deep scholarship she shows us how reclaiming this fertile, soporific energy--an energy that lives within us all--can help heal our connection with the Animate Everything and nourish the re-flowering of the world.”

“Readers will feel the words in this book tendril around their hearts and minds, forming adaptive connections and creating conversations with the ‘Animate Everything’ in the wilds of their everyday worlds. Myths that stay the same don’t survive, Strand tells us; she waves a wand toward the earth and summons up vital wisdom for our time.”

Descriere

Sharing eight years of research, Strand leads us back into the forgotten landscapes and hidden secrets of familiar myths, revealing the beautiful range of the divine masculine.