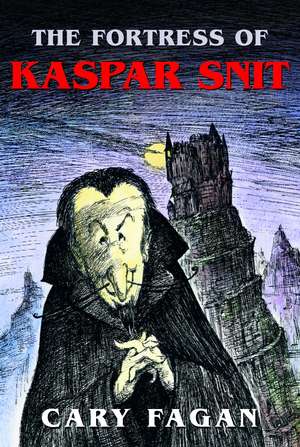

The Fortress of Kaspar Snit

Autor Cary Faganen Limba Engleză Paperback – 29 feb 2004 – vârsta de la 8 până la 12 ani

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Kaspar Snit is a villainous villain who is determined to steal all the fountains in the world. Why? Fountains are beautiful and give people pleasure, two things he can’t abide.

Can a family of four who love fountains rescue them from the hands of this dastardly scoundrel? Especially when that family is made up of the four most eccentric individuals you’d care to meet?

Eleven-year-old Eleanor, eight-year-old Solly, better known as Googoo Man, and their parents, who are, to say the least, odd, set out on a hilarious quest over mountains and across the seas to storm the fortress of Kaspar and retrieve the lost fountains.

Cary Fagan’s first novel for children is a fun fantasy that will keep young armchair travelers laughing right to the exciting end.

Preț: 51.54 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 77

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.86€ • 10.26$ • 8.14£

9.86€ • 10.26$ • 8.14£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780887766657

ISBN-10: 088776665X

Pagini: 167

Dimensiuni: 128 x 197 x 9 mm

Greutate: 0.16 kg

Editura: Tundra Books (NY)

ISBN-10: 088776665X

Pagini: 167

Dimensiuni: 128 x 197 x 9 mm

Greutate: 0.16 kg

Editura: Tundra Books (NY)

Notă biografică

Cary Fagan is an award-winning writer for both young readers and adults. In addition to several picture books published with Tundra, he also wrote the award-winning biography of Chan Hon Goh, Beyond the Dance: A Ballerina’s Life. He has won a Mr. Christie Silver Medal for Daughter of the Great Zandini, a City of Toronto Book Award for his first adult novel, and the Jewish Book Committee Prize for Fiction. Cary Fagan lives in Toronto.

Extras

Chapter 1

THE UNDERPANTS PETITION

We were in the middle of dinner when I said, “Why can’t I learn to fly?”

My mother had been raising a forkful of lasagna to her mouth, but she stopped to give me the look. You know that look – the one that parents give when you’ve asked for something once too often.

I guess my father didn’t hear – he was always thinking of something else – because he said, “I got a very interesting offer today. There’s a fountain in Istanbul, eight hundred years old, hasn’t worked for centuries. The Turkish government wants me to advise them on how to restore it. The water source comes from a stream…”

“If Eleanor gets to learn to fly, then I want to learn too,” said Solly. His name was Saul, but everybody called him Solly. Maybe when he was older he wouldn’t let anyone call him Solly anymore, but right now he was seven years old and a shrimp. Actually, he never called himself Saul or Solly. Not at home. Not at school. Not at the park. Not anywhere, ever. He always called himself Googoo-man. In my opinion, it was the most ridiculous name for a superhero ever imagined. But it came about because “goo-goo” was the first sound Solly ever made and, somehow, it stuck in that pea-sized brain of his.

As always, Solly had come to dinner dressed in his Googoo-man superhero outfit. Green stretchy pajamas with a red bathing suit pulled over it. A cape made from a bath towel with the words property of hotel schmutz printed on it. Swim goggles and rubber bathing cap with chin strap. Swim flippers. Belt made from a thousand elastic bands tied together. Two weapons tucked into the belt: a “sonic blaster” (bicycle horn) and a “neutronic knocker” (old sock filled with unidentifiable substance). Would you trust a seven-year-old kid dressed this way to save the world?

“You’re too young to fly,” I snapped, “just a kid. You can have fun pretending, like you always do. But I’m too old to pretend. I’m old enough–”

“You’re both kids,” my mother said wearily. “And for the hundredth time, no, Eleanor, you can’t learn to fly.”

“What’s that?” my father said, blinking. “Eleanor, are you starting up again? You know your mother’s and my attitude about that. There will be no children learning to fly in this house.”

“But it isn’t fair!” I insisted. “I really am old enough. I have lots of responsibilities now. I have to walk Solly to school. I have to make my bed. I have to clear the table. Why can’t I have any fun responsibilities? What’s the use of being eleven if I can never do anything I want?”

“You get to do lots of things that you want,” Mom said, trying to sound understanding. “You went to a movie with your friends last week, didn’t you? Your father is a grown-up and he doesn’t fly.”

“That’s because he doesn’t want to. But I do.”

My mother looked at my father and raised her eyebrows. She knew it was true. But my father shook his head. “Listen, Eleanor,” he said, “I know how tempting it must seem. But your mother and I agreed before we even got married – didn’t we, Daisy? – that there would be no more flying in her family. Mom would be the last one. We want you and Solly to be normal, everyday children enjoying normal, everyday things. We want you to be just like everybody else. And being able to fly isn’t exactly like everybody else, is it?” My father flicked out his arm to uncover his watch from under his shirt cuff. “See? It’s getting late. The fountain turn-off ceremony is supposed to be in ten minutes.”

“I don’t feel like going to the ceremony,” I said.

“Of course you do.” My father smiled. “It’s a family tradition.”

My mother looked at me sympathetically. “Maybe we should excuse Eleanor just tonight, Manfred.”

“Never mind,” I said. “I’ll come to the dumb ceremony. And by the way, Dad, there’s nothing normal about a fountain turn-off ceremony. I mean, do you see anybody else on the street having one?”

“That’s different,” Dad said. “It’s still in the realm of regular human behavior. It doesn’t require any – well, any special powers. There’s nothing freakish about it.”

“Manfred!” Mom cried. “Do you think I’m a freak?”

“Of course not.” Dad put his hand on his high forehead. “This conversation never ends well.”

“But flying would be so cool,” I said, even though I knew it was a lost cause. “Nobody would have to know about it. I’d keep it a secret. Solly would keep it a secret too, wouldn’t you, Solly?”

Solly just looked at me and grinned, his mouth full of lasagna. A big help he was. I turned back to my parents. “A fountain is definitely not cool. A fountain – especially our fountain – is embarrassing.”

“That’s enough, Eleanor Galinski Blande,” Mom said.

“It’s time,” Dad said, putting down his napkin and pushing away from the table.

A couple of years ago, my mother gave me a book called The Big Orange Splot by Daniel Pinkwater (I swear that’s his real name). In this book a man decides to paint his house all kinds of crazy colors. At first the neighbors don’t like it, but then each neighbor gets inspired to decorate his own house just the way he likes it. Mom gave me this book to help me understand what Dad did to our house. I think she hoped that, after reading the book, I wouldn’t be so embarrassed.

Well, I read the book, and I was still embarrassed. The reason was simple: none of the other families on our street changed their houses. They stayed just as they were before – regular houses, each with a garage and a square of grass and a little flower bed and a spindly tree. I guess our neighbors never got the message.

Actually, there was nothing strange about our house itself. It looked just like the bungalow three doors down and the one three doors up. It was what was in front of our house that was different. The reason that the four of us now marched single file, Solly’s flippers making flopping noises, out the front door and onto the sidewalk.

A fountain.

A fountain? Not so bad, you might think. Fountains are kind of nice, aren’t they? But this was a big fountain. A very big fountain. A monumentally big fountain.

As we stood on the sidewalk I was struck, as always, by how it filled our entire front yard, right to the sidewalk’s edge. It began with a big square basin, with marble sides that rose as high as my waist. The basin held a pool of water: ten thousand gallons, to be precise. Out of the middle rose eight winged horses, carved out of marble and larger than life. The horses reared up on their hind legs, heads held high, eyes wild, nostrils flaring. On the back of each horse was a man or a woman (four of each) holding conch shells, out of which spouted jets of water that splashed down to the basin. The men were very handsome and the women beautiful, with sculpted faces that looked alive and flowing marble hair and magnificently formed arms and legs.

They were also totally naked.

Which meant that we had four naked women and four naked men on our front lawn. That added up to eight butts. It was well known in the neighborhood that the first naked people little kids around here ever saw (besides their own family) were the statues of our fountain. They discovered what people look like without clothes on by staring at our fountain. Mothers were always pulling their open-mouthed kids away from the sidewalk in front of our house. Once, around dinnertime, I caught a teenaged boy gazing at the second woman on the right. I swear he looked like he had fallen in love with her. I opened the front door and shouted, “Move it, buster! What do you think this is, health education class?” Boy, did he take off.

After we were properly lined up, my father took two steps forward. He opened a little door in the side of the basin that was invisible unless you knew where to look. Inside the tiny compartment was a small wheel-like tap and, as my father now turned it, the streams of water shooting from the conch shells slumped lower and lower until they became just a drip. Without the sound of the falling water, everything turned quiet. My father patted the side of the fountain and my mother said, “All right, everybody, back inside.”

As we filed in again, I noticed our next-door neighbor Mr. Worthington, along with his children Jeremy and Julia, watching us through the parted curtains of their front window. Mr. Worthington had once taken a petition up and down the street. He knocked on every door wearing his bowler hat, and with his umbrella on his arm. The petition demanded that my father put underpants and T-shirts on the statues. In defense of public decency, it said. After he got a whole sheet of signatures, Mr. Worthington knocked on our door and solemnly presented the petition to my father. Dad read it over and, thinking that Mr. Worthington was making a joke, laughed so hard that he couldn’t breathe. He had to lie down right in the front hall. Mr. Worthington just looked at my father until finally he put his bowler hat back on and returned to his own house.

But after that, my father did start the fountain turn-off ceremony. It’s surprising how noisy all that whooshing water can be and my father decided that, while he found the sound very soothing, not all the neighbors likely appreciated it. He turned it on again at precisely 6:45 a.m., but he didn’t expect us to get up and watch. Sometimes I came out anyway and, when my father turned the tap, there would be a little spurt from each conch shell, then a bigger spurt, and finally a gusher. At that moment all the neighborhood dogs would howl.

We began filing back into the house, with my father at the front and me coming up the rear. I felt a tap on my shoulder and turned around to see Julia Worthington standing on the sidewalk behind me. She was wearing her leotard, her hair pulled back in a bun.

“Hi, Eleanor,” she said.

“Hi, Julia.”

“Doing that crazy fountain thing, huh?” She made a goofy face, crossing her eyes and twisting her mouth to one side.

“I guess so,” I said.

“I just learned how to do a triple back flip. I’m going to do it in my freestyle program for the June finals. You want to see it?”

No, I didn’t want to see Julia Worthington do a stupid back flip. But I didn’t have the courage or the guts or whatever it took to say so and just nodded instead. She stepped onto her own lawn – unlike ours, it had actual grass – and before I could blink, she was flipping backwards in the air, landing on her hands, and flipping again. The sour truth is, I was hoping she’d crash onto her rear end but she didn’t and, when she came up after the third time, she had a smile fixed on her face like she was trying to impress a jury of Olympic judges.

“That’s … that’s great, Julia.”

“Thanks. Well, I’ve got to go. I have to practise the harp now. I’m learning a new Mozart piece.”

She gave a little wave and ran up her porch stairs. That was another thing about Julia. She couldn’t play the piano or the trumpet like everybody else. She had to play the harp. She played at every school assembly, her hands running across all those harp strings to make a sound like a musical waterfall. Julia never did anything that anybody else did – unless she could do it better. It was weird, considering how much I didn’t like her (although I wasn’t even sure if it was fair that I didn’t like her), that I still wished she would be my friend. I stood alone on the sidewalk a minute and then I trudged back into the house.

In the night, I woke up and couldn’t get back to sleep. I listened to the sound of Solly in the next room, whistling through his nose while he slept. The chair at my desk cast a long shadow against the wall that looked like the bars of a cage. It felt as if, even before I woke up, I’d been thinking about my friends at school, especially Julia Worthington. Everyone liked Julia and I didn’t think that I’d ever seen her alone at school. She always had one or two girlfriends with her in the hall, or the washroom, or at recess. I mean, it wasn’t like I was some friendless loner exactly, but I always felt on the edge of things, as if it didn’t really make a difference whether I was sitting with the other girls at lunch or going along to the movie. There wasn’t anything special about me, anything to make them really, really like me.

I made myself close my eyes, but I knew that I wouldn’t be able to go back to sleep right away so I got up and went over to the window. In the dark I could see the shape of our swing and teeter-totter set that I used to love so much when I was little. Over the back fence were the roofs of other houses and a couple of old tv antennas, even though people didn’t use them anymore. Two or three stars in the sky. And then, above the trees and maybe four or five streets away, I saw my mother moving through the night sky – the wind blowing back her hair, her hands near her sides, and her toes pointed back. So she was flying tonight. How I wished that I knew how she did it! How I wished that I could fly too! It seemed to me that just about everything would be better if I could. I watched as my mother rose higher and veered away, disappearing behind the rise of trees from the neighborhood park. It wasn’t fair that she wouldn’t teach me, that I had to be just like regular kids when I wanted to be special too. Well, maybe if she wouldn’t teach me, I would have to find out for myself. After all, that’s what Mom did.

Determined now, I climbed back into bed.

THE UNDERPANTS PETITION

We were in the middle of dinner when I said, “Why can’t I learn to fly?”

My mother had been raising a forkful of lasagna to her mouth, but she stopped to give me the look. You know that look – the one that parents give when you’ve asked for something once too often.

I guess my father didn’t hear – he was always thinking of something else – because he said, “I got a very interesting offer today. There’s a fountain in Istanbul, eight hundred years old, hasn’t worked for centuries. The Turkish government wants me to advise them on how to restore it. The water source comes from a stream…”

“If Eleanor gets to learn to fly, then I want to learn too,” said Solly. His name was Saul, but everybody called him Solly. Maybe when he was older he wouldn’t let anyone call him Solly anymore, but right now he was seven years old and a shrimp. Actually, he never called himself Saul or Solly. Not at home. Not at school. Not at the park. Not anywhere, ever. He always called himself Googoo-man. In my opinion, it was the most ridiculous name for a superhero ever imagined. But it came about because “goo-goo” was the first sound Solly ever made and, somehow, it stuck in that pea-sized brain of his.

As always, Solly had come to dinner dressed in his Googoo-man superhero outfit. Green stretchy pajamas with a red bathing suit pulled over it. A cape made from a bath towel with the words property of hotel schmutz printed on it. Swim goggles and rubber bathing cap with chin strap. Swim flippers. Belt made from a thousand elastic bands tied together. Two weapons tucked into the belt: a “sonic blaster” (bicycle horn) and a “neutronic knocker” (old sock filled with unidentifiable substance). Would you trust a seven-year-old kid dressed this way to save the world?

“You’re too young to fly,” I snapped, “just a kid. You can have fun pretending, like you always do. But I’m too old to pretend. I’m old enough–”

“You’re both kids,” my mother said wearily. “And for the hundredth time, no, Eleanor, you can’t learn to fly.”

“What’s that?” my father said, blinking. “Eleanor, are you starting up again? You know your mother’s and my attitude about that. There will be no children learning to fly in this house.”

“But it isn’t fair!” I insisted. “I really am old enough. I have lots of responsibilities now. I have to walk Solly to school. I have to make my bed. I have to clear the table. Why can’t I have any fun responsibilities? What’s the use of being eleven if I can never do anything I want?”

“You get to do lots of things that you want,” Mom said, trying to sound understanding. “You went to a movie with your friends last week, didn’t you? Your father is a grown-up and he doesn’t fly.”

“That’s because he doesn’t want to. But I do.”

My mother looked at my father and raised her eyebrows. She knew it was true. But my father shook his head. “Listen, Eleanor,” he said, “I know how tempting it must seem. But your mother and I agreed before we even got married – didn’t we, Daisy? – that there would be no more flying in her family. Mom would be the last one. We want you and Solly to be normal, everyday children enjoying normal, everyday things. We want you to be just like everybody else. And being able to fly isn’t exactly like everybody else, is it?” My father flicked out his arm to uncover his watch from under his shirt cuff. “See? It’s getting late. The fountain turn-off ceremony is supposed to be in ten minutes.”

“I don’t feel like going to the ceremony,” I said.

“Of course you do.” My father smiled. “It’s a family tradition.”

My mother looked at me sympathetically. “Maybe we should excuse Eleanor just tonight, Manfred.”

“Never mind,” I said. “I’ll come to the dumb ceremony. And by the way, Dad, there’s nothing normal about a fountain turn-off ceremony. I mean, do you see anybody else on the street having one?”

“That’s different,” Dad said. “It’s still in the realm of regular human behavior. It doesn’t require any – well, any special powers. There’s nothing freakish about it.”

“Manfred!” Mom cried. “Do you think I’m a freak?”

“Of course not.” Dad put his hand on his high forehead. “This conversation never ends well.”

“But flying would be so cool,” I said, even though I knew it was a lost cause. “Nobody would have to know about it. I’d keep it a secret. Solly would keep it a secret too, wouldn’t you, Solly?”

Solly just looked at me and grinned, his mouth full of lasagna. A big help he was. I turned back to my parents. “A fountain is definitely not cool. A fountain – especially our fountain – is embarrassing.”

“That’s enough, Eleanor Galinski Blande,” Mom said.

“It’s time,” Dad said, putting down his napkin and pushing away from the table.

A couple of years ago, my mother gave me a book called The Big Orange Splot by Daniel Pinkwater (I swear that’s his real name). In this book a man decides to paint his house all kinds of crazy colors. At first the neighbors don’t like it, but then each neighbor gets inspired to decorate his own house just the way he likes it. Mom gave me this book to help me understand what Dad did to our house. I think she hoped that, after reading the book, I wouldn’t be so embarrassed.

Well, I read the book, and I was still embarrassed. The reason was simple: none of the other families on our street changed their houses. They stayed just as they were before – regular houses, each with a garage and a square of grass and a little flower bed and a spindly tree. I guess our neighbors never got the message.

Actually, there was nothing strange about our house itself. It looked just like the bungalow three doors down and the one three doors up. It was what was in front of our house that was different. The reason that the four of us now marched single file, Solly’s flippers making flopping noises, out the front door and onto the sidewalk.

A fountain.

A fountain? Not so bad, you might think. Fountains are kind of nice, aren’t they? But this was a big fountain. A very big fountain. A monumentally big fountain.

As we stood on the sidewalk I was struck, as always, by how it filled our entire front yard, right to the sidewalk’s edge. It began with a big square basin, with marble sides that rose as high as my waist. The basin held a pool of water: ten thousand gallons, to be precise. Out of the middle rose eight winged horses, carved out of marble and larger than life. The horses reared up on their hind legs, heads held high, eyes wild, nostrils flaring. On the back of each horse was a man or a woman (four of each) holding conch shells, out of which spouted jets of water that splashed down to the basin. The men were very handsome and the women beautiful, with sculpted faces that looked alive and flowing marble hair and magnificently formed arms and legs.

They were also totally naked.

Which meant that we had four naked women and four naked men on our front lawn. That added up to eight butts. It was well known in the neighborhood that the first naked people little kids around here ever saw (besides their own family) were the statues of our fountain. They discovered what people look like without clothes on by staring at our fountain. Mothers were always pulling their open-mouthed kids away from the sidewalk in front of our house. Once, around dinnertime, I caught a teenaged boy gazing at the second woman on the right. I swear he looked like he had fallen in love with her. I opened the front door and shouted, “Move it, buster! What do you think this is, health education class?” Boy, did he take off.

After we were properly lined up, my father took two steps forward. He opened a little door in the side of the basin that was invisible unless you knew where to look. Inside the tiny compartment was a small wheel-like tap and, as my father now turned it, the streams of water shooting from the conch shells slumped lower and lower until they became just a drip. Without the sound of the falling water, everything turned quiet. My father patted the side of the fountain and my mother said, “All right, everybody, back inside.”

As we filed in again, I noticed our next-door neighbor Mr. Worthington, along with his children Jeremy and Julia, watching us through the parted curtains of their front window. Mr. Worthington had once taken a petition up and down the street. He knocked on every door wearing his bowler hat, and with his umbrella on his arm. The petition demanded that my father put underpants and T-shirts on the statues. In defense of public decency, it said. After he got a whole sheet of signatures, Mr. Worthington knocked on our door and solemnly presented the petition to my father. Dad read it over and, thinking that Mr. Worthington was making a joke, laughed so hard that he couldn’t breathe. He had to lie down right in the front hall. Mr. Worthington just looked at my father until finally he put his bowler hat back on and returned to his own house.

But after that, my father did start the fountain turn-off ceremony. It’s surprising how noisy all that whooshing water can be and my father decided that, while he found the sound very soothing, not all the neighbors likely appreciated it. He turned it on again at precisely 6:45 a.m., but he didn’t expect us to get up and watch. Sometimes I came out anyway and, when my father turned the tap, there would be a little spurt from each conch shell, then a bigger spurt, and finally a gusher. At that moment all the neighborhood dogs would howl.

We began filing back into the house, with my father at the front and me coming up the rear. I felt a tap on my shoulder and turned around to see Julia Worthington standing on the sidewalk behind me. She was wearing her leotard, her hair pulled back in a bun.

“Hi, Eleanor,” she said.

“Hi, Julia.”

“Doing that crazy fountain thing, huh?” She made a goofy face, crossing her eyes and twisting her mouth to one side.

“I guess so,” I said.

“I just learned how to do a triple back flip. I’m going to do it in my freestyle program for the June finals. You want to see it?”

No, I didn’t want to see Julia Worthington do a stupid back flip. But I didn’t have the courage or the guts or whatever it took to say so and just nodded instead. She stepped onto her own lawn – unlike ours, it had actual grass – and before I could blink, she was flipping backwards in the air, landing on her hands, and flipping again. The sour truth is, I was hoping she’d crash onto her rear end but she didn’t and, when she came up after the third time, she had a smile fixed on her face like she was trying to impress a jury of Olympic judges.

“That’s … that’s great, Julia.”

“Thanks. Well, I’ve got to go. I have to practise the harp now. I’m learning a new Mozart piece.”

She gave a little wave and ran up her porch stairs. That was another thing about Julia. She couldn’t play the piano or the trumpet like everybody else. She had to play the harp. She played at every school assembly, her hands running across all those harp strings to make a sound like a musical waterfall. Julia never did anything that anybody else did – unless she could do it better. It was weird, considering how much I didn’t like her (although I wasn’t even sure if it was fair that I didn’t like her), that I still wished she would be my friend. I stood alone on the sidewalk a minute and then I trudged back into the house.

In the night, I woke up and couldn’t get back to sleep. I listened to the sound of Solly in the next room, whistling through his nose while he slept. The chair at my desk cast a long shadow against the wall that looked like the bars of a cage. It felt as if, even before I woke up, I’d been thinking about my friends at school, especially Julia Worthington. Everyone liked Julia and I didn’t think that I’d ever seen her alone at school. She always had one or two girlfriends with her in the hall, or the washroom, or at recess. I mean, it wasn’t like I was some friendless loner exactly, but I always felt on the edge of things, as if it didn’t really make a difference whether I was sitting with the other girls at lunch or going along to the movie. There wasn’t anything special about me, anything to make them really, really like me.

I made myself close my eyes, but I knew that I wouldn’t be able to go back to sleep right away so I got up and went over to the window. In the dark I could see the shape of our swing and teeter-totter set that I used to love so much when I was little. Over the back fence were the roofs of other houses and a couple of old tv antennas, even though people didn’t use them anymore. Two or three stars in the sky. And then, above the trees and maybe four or five streets away, I saw my mother moving through the night sky – the wind blowing back her hair, her hands near her sides, and her toes pointed back. So she was flying tonight. How I wished that I knew how she did it! How I wished that I could fly too! It seemed to me that just about everything would be better if I could. I watched as my mother rose higher and veered away, disappearing behind the rise of trees from the neighborhood park. It wasn’t fair that she wouldn’t teach me, that I had to be just like regular kids when I wanted to be special too. Well, maybe if she wouldn’t teach me, I would have to find out for myself. After all, that’s what Mom did.

Determined now, I climbed back into bed.

Premii

- Manitoba Young Readers Choice Award Nominee, 2006