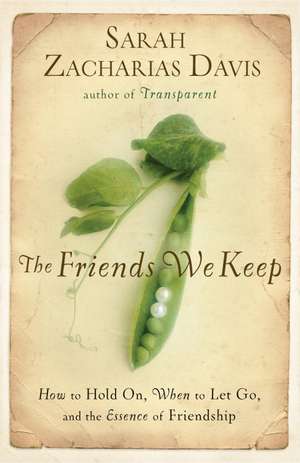

The Friends We Keep: A Woman's Quest for the Soul of Friendship

Autor Sarah Zacharias Davisen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2009

During a particularly painful time in her life, Sarah Zacharias Davis learned how delightful–and wounding–women can be in friendship. She saw how some friendships end badly, others die slow deaths, and how a chance acquaintance can become that enduring friend you need.

The Friends We Keep is Sarah’s thoughtful account of her own story and the stories of other women about navigating friendship. Her revealing discoveries tackle the questions every woman asks:

• Why do we long so for women friends?

• Do we need friends like we need air or food or water?

• What causes cattiness, competition, and co-dependency in too many friendships?

• Why do some friendships last forever and others only a season?

• How do I foster friendship?

• When is it time to let a friend go, and how do I do so?

With heartfelt, intelligent writing, Sarah explores these questions and more with personal stories, cultural references and history, faith, and grace. In the process, she delivers wisdom for navigating the challenges, mysteries, and delights of friendship: why we need friendships with other women, what it means to be safe in relationship, and how to embrace what a friend has to offer, whether meager or generous.

Preț: 98.41 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 148

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.83€ • 19.59$ • 15.55£

18.83€ • 19.59$ • 15.55£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 08-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400074396

ISBN-10: 1400074398

Pagini: 210

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Waterbrook Press

ISBN-10: 1400074398

Pagini: 210

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Waterbrook Press

Notă biografică

Sarah Zacharias Davis is an senior advancement officer at Pepperdine University, having joined the university after working as vice president of marketing and development for Ravi Zacharias International Ministries and in strategic marketing for CNN. The daughter of best-selling writer Ravi Zacharias, Davis is the author of the critically-acclaimed Confessions from an Honest Wife and Transparent: Getting Honest About Who We are and Who We Want to Be. She graduated from Covenant College with a degree in education and lives in Los Angeles, California.

Extras

My eyes flooded with tears that began rolling down my face. Horrified at my public display of grief, I had to keep myself from all-out sobbing over Isabel’s death before the person sitting next to me on the plane thought me mentally unstable and requested to be moved to another seat.

This was my third time reading the book The Saving Graces, and I cried all three times when each of the friends read Isabel’s letters after her death. I stumbled upon The Saving Graces, a novel by Patricia Gaffney, one evening when perusing Barnes & Noble for something good. The words “New York Times Bestseller” caught my eye, and I decided to give Gaffney a try, though I was unfamiliar with anything she

had written.

The Saving Graces is the story of four friends and how each is there for the others through the ups and downs of life: childlessness, broken relationships, love, illness, and death. I read the book three times because I wanted to join the friendship circle of Lee, Rudy, Isabel, and Emma again and because it deeply impacted the way I viewed friendship, both the kind of friendships I wanted and the kind of friend I wanted to be. For me The Saving Graces raised the bar, as well as the stakes.

I loved the way the others supported Rudy when she moved out of her home and through the abuse she encountered.The unmitigated appreciation for each individual friend was evidenced as Isabel wrote parting letters to her three friends. I was inspired by the manner with which the friends got snippy with each other, and yet quickly forgave and forgot.

Finally, I was moved by how the loss of one left an enormous hole that could not, nor would, ever be filled in the others. I found this especially, exquisitely stunning, thus moving me to tears each time I shared these women’s lives.They were there to defend, laugh, comfort, give physical care, and even

give space—all that real life requires. These were friendships of depth and honesty, strength and longevity. These friends loved each other in all their messiness. No one had to bring perfection to the friendship, only loyalty.

My reluctance to leave the world of the four women and close the book for the third time invited explorational thoughts of friendship. What was it about their friendships that left me reluctant to leave their company and return to my own life? Is that what my friendships were supposed to look like? Did I need to find a Rudy, an Isabel, a Lee, or an Emma to fill the longing that this novel surreptitiously uncovered in my soul? Did my own small collection of friendships seem not enough compared to the bond these four shared? And why not? Was it the way they supported one another or the way they alwaysmade time for one another? Or was it the way one could behave in a manner that was very unlovable and yet still remain loved?

At the risk of making a grand, sweeping gender statement, I’ll point out that some men seem to have categories of friends. They have work friends, friends for playing weekly pickup basketball games, golfing friends, and friends forced on them by a significant other. Seldom do they see these friends outside their category of identity, yet they would call them friends.

Many of the friendships women hold, however, seem to make their way beyond the circumstances that brought them together and meander into their lives through both the valleys and the peaks, eventually ending up in the women’s souls, where they can both restore and destruct. And yet, isn’t a real friendship one that would bring both the yin and the yang, so to speak? Is the multidimensional aspect of the relationship the very characteristic that makes it a true friendship?Would I have been so captivated and, yes, envious of the saving graces if their friendships contained no shadows?

History is rife with story upon story of love, commitment, bravery, loyalty, betrayal, and disappointment—all within friendships. And in our own personal histories, many of the same stories can be told Friendship is a relationship we desire and cultivate early in our development, whether we had an imaginary friend as a constant companion or we began the first day of school as a shy, pigtailed little girl inviting another to be our friend.

For a woman, the connection to friendship is innate and essential. It feels so vital to life and to living that the desire for it seems part of our fabric of being. Cicero said friendship “springs from nature rather than from need—from an inclination of the mind with a certain consciousness of love.”1 This is certainly true across generations and cultures. Early Chinese culture held women’s friendships as almost sacred. In her beautiful work of historical fiction Snow Flower and the Secret Fan, Lisa See educates her readers about sacred friendship practices.2 The Chinese women of this patriarchal culture committed themselves to very deep friendships, knowing there was substance and soul that could exist in no other relationships.

There were two types of soul friendships: sworn sisters and laotongs, which means “old same.” Sworn sisterhoods were groups of unmarried women who became friends.These sisterhoods dissolved at the time of marriage. A laotong relationship was between two girls from different villages.Many superstitions were observed before two girls would be found to be a match.They were usually the same age and both born in auspicious years, according to the tradition. The girls were bound together in lifelong friendship, in a ceremony that was nearly equivalent to a marriage ceremony in its commitments and gravity.The larger world only learned of the existence of this tradition of special friendships when, in a crowded train station at the height of China’s Cultural Revolution, a woman was detained as a suspected spy after

fainting. Authorities searched her belongings in an effort to identify her and found papers written in a language none could identify. Scholars were brought in to examine the writings, and they discovered that the elderly woman was not a spy after all; rather, her writings were in a secret language used only by women in the region of Yao. This language was a secret for more than a thousand years.

Sadly, most of the writings in nu shu have not survived over the years as they were either buried with the women at their death to accompany them to the other world or destroyed in the revolution. In the twentieth century, the nu shu language is all but extinct and no longer needed. But its existence and use discloses the depth of friendship and community among these women—and the universal, powerful longing for friendship that exists among us, the desire to be known and heard.

How do you know your friends, and how do you find them?Most of us look back on lives decorated with stories of friendships from the time we were young. There are the friends we hurried home from school to play with every day. After donning play clothes and perhaps wolfing down a snack, we’d join them for some clandestine adventure until we were summoned to dinner at dusk. There are the friends who gave us our social life when we were teenagers, inviting us to something somewhere that opened an entire new world of cliques, jealousy, loyalty, and, ultimately, resiliency. There are the friends of our early twenties, alongside whom we entered independence, straddling worlds of codependency and experimental autonomy. There are the friends who champion us through many of the celebrations and disappointments of adult life, from marriage and professional promotions to buying a first home and having children, along with a myriad of heartbreaks and losses.

And there’s every kind of friend in between. The friend you go to the ballet with; the friend you shop with—the one who talks you into a regrettable purchase every time; the one who will tell you what you want to hear and the one who has the courage to tell you what you don’t; the friend from whom you always get the latest news on everyone else; the one who will listen when you need to be heard and the one who will talk when you only have energy to listen. There’s the role model, the mentor, and the friend with whom you have a love-hate relationship.There are group and work friendships, friendships within a larger community, the “our children are best friends” and “our husbands are best friends” relationships.

If so many different types of connections are called friendships, do they all come from the same well, some single essence of friendship?What is it that creates a friendship? Is it social obligation, the fact that you wanted a large wedding party so the pictures would look better, necessity, or essential longing? And if it is longing, is the primary catalyst our longing for someone’s friendship or that person’s longing for ours? Do we need to know the answers to these questions to be a good friend or to have a fulfilling friendship—or am I simply overanalyzing that which just happens naturally?

My worn paperback copy of The Saving Graces placed back on my shelf of fiction between authors Fielding and Grisham, these were the questions I went looking to answer.

For centuries poets, authors, and song and screenplay writers have sought to define friendship—with results ranging from Aristotle’s conclusion that friendship is “a single soul dwelling in two bodies” to Ralph Waldo Emerson’s description of a friend as “a person with whom I may be sincere.”3

Certainly a distinction should be made between an acquaintance and a true friend. Is friendship simply companionship? For me, this is not the case. The Saving Graces taught me a narrower, even sacred definition of friendship.

What qualifies someone to be called your friend?

I read a sweet story by F.W. Boreham about a little boy plagued by nightmares.4 Rather than visions of sugarplums, a frightening tiger intrudes on the boy’s dreams. Night after night, the child wakes in fear, a cold sweat, and a rapidly beating heart. His parents are concerned (and probably lacking sleep if the boy is crawling into bed with them each night), and they send him to a child psychologist. After listening to the boy recount his dreams, the psychologist gets an idea. He tells the child, “The tiger visiting you is actually a good tiger. He wants to be your friend. So next time the tiger appears in your dream, simply put your hand out to shake his paw and say, ‘Hello, old chap!’ ”

And so, the story goes, that very same night the boy asleep in his bed suddenly becomes restless. He thrashes about in his bed, sweating and crying out in his sleep, until a small hand, partly hidden by cotton pajamas, suddenly juts out from the covers, followed by a sleepy little voice saying, “Hello, old chap!” Thus he made friends with the tiger.

That story makes me smile, and I suppose, partly, this is because of the old English language that scripts a little boy using amusing terms like “old chap.” But is that how it’s done? Is mere familiarity how friendships are forged? Does simply banishing the title of stranger make way for friendship? Or is something more required?

Perhaps it is the banishing of danger.The reason the tiger trick worked on the little boy’s nightmares was that it removed the danger.Maybe that works inmaking friends too. Maybe, beyond simple introductions so thatwe are no longer strangers, we enter a shared space with a person that we hope is safe—safe for us to be ourselves and to be real.

What creates that safe space? Is it simply shared interest or geography? Is friendship born in similar goals or experiences? What about behavior? If two people act in a certain way toward each other, are they friends? If so, then what does friendship look like?

As I thought about how art imitates life, and ever a lover of art, paintings, literature, poetry, films, and music, I mulled the characteristics of friendship and the numerous recent pictures of friendship, specifically women’s friendships.When I interact with these different mediums, something in them resonates with me, something that moves me, and I stop and notice.Whether it’s a tearjerker movie, a painting whose brush strokes create a gentle gesture, or lyrics so poignant, art inspires me to pay attention to what is within myself.

In the 1980s film The Four Seasons, the opening scene depicts three couples going away for a few days in the spring. Toasts and speeches characterize this holiday together, and the couples celebrate the depth of their friendships.We learn that the men were introduced to each other after the women became friends. The following season, summer, one friend is missing. During the previous few months, one couple has divorced and a cute young girlfriend has joined the circle to now complete the six. I couldn’t help but wonder what happened to the wife. Why is she eliminated from the circle of friends? And if the

women were the original friends, why have they agreed to oust her from the group?Why doesn’t the divorced couple at least get joint custody of their friends?

Throughout the movie’s four seasons, we see what each friend brings to the circle of friendship. We see the idiosyncrasies, bad habits, and selfishness, but also the commitment to one another through all the terrain in each season of friendship. And when one woman cries out in sheer frustration that, in spite of it all, she needs her friends and always will, we feel the truth of her statement reverberate through us.This was a climactic exclamation aftermonths of tension created by selfishness, lack of awareness, and judgment between the friends.

But yes, in spite of the hurts our friendships can cause, we need them, we want them.

Growing up I adored reading and seeing films of Anne of Green Gables. I still do. Anne, an imaginative and precocious orphan, comes to live with an aging pair of siblings, neither of whom has ever married. Marilla, a salty, no-nonsense woman, doesn’t have either the understanding or the patience for Anne’s emotions and antics. Matthew, her brother, is a soft-spoken and kindhearted man, though timid too.When Anne arrives in Avonlea and is invited to become part of Matthew andMarilla Cuthbert’s family, she sets out to make a friend. But Anne isn’t looking for just any acquaintance; rather, she is in search of a “kindred spirit,” a “bosom friend.”

“A—a what kind of a friend?”Marilla asked her, puzzled.

“A bosom friend—an intimate friend, you know—” Anne replied, “a really kindred spirit to whom I can confide my inmost soul. I’ve dreamed of meeting her all my life. I never really supposed I would, but so many of my loveliest dreams have come true all at once that perhaps this one will too. Do you think it’s possible?”

Later, after learningmore about a potential bosom friend, Anne adds one more requirement: “Oh, I’m so glad she’s pretty.Next to being beautiful oneself—and that’s impossible in my case—it would be best to have a beautiful bosom friend.”5

With the unflinching honesty of a child, Anne expresses what we all secretly desire: a best, kindred-spirit kind of friend. The older we get, the more reluctant we are to ask for what we want or need, but Anne does so unabashedly. And in her eyes, her friendship with Diana ismade even better when her new friend is someone that Anne herself is convinced she could never be. Could it be that we go in search of friends who embody something we wish we were or long to be?

This was my third time reading the book The Saving Graces, and I cried all three times when each of the friends read Isabel’s letters after her death. I stumbled upon The Saving Graces, a novel by Patricia Gaffney, one evening when perusing Barnes & Noble for something good. The words “New York Times Bestseller” caught my eye, and I decided to give Gaffney a try, though I was unfamiliar with anything she

had written.

The Saving Graces is the story of four friends and how each is there for the others through the ups and downs of life: childlessness, broken relationships, love, illness, and death. I read the book three times because I wanted to join the friendship circle of Lee, Rudy, Isabel, and Emma again and because it deeply impacted the way I viewed friendship, both the kind of friendships I wanted and the kind of friend I wanted to be. For me The Saving Graces raised the bar, as well as the stakes.

I loved the way the others supported Rudy when she moved out of her home and through the abuse she encountered.The unmitigated appreciation for each individual friend was evidenced as Isabel wrote parting letters to her three friends. I was inspired by the manner with which the friends got snippy with each other, and yet quickly forgave and forgot.

Finally, I was moved by how the loss of one left an enormous hole that could not, nor would, ever be filled in the others. I found this especially, exquisitely stunning, thus moving me to tears each time I shared these women’s lives.They were there to defend, laugh, comfort, give physical care, and even

give space—all that real life requires. These were friendships of depth and honesty, strength and longevity. These friends loved each other in all their messiness. No one had to bring perfection to the friendship, only loyalty.

My reluctance to leave the world of the four women and close the book for the third time invited explorational thoughts of friendship. What was it about their friendships that left me reluctant to leave their company and return to my own life? Is that what my friendships were supposed to look like? Did I need to find a Rudy, an Isabel, a Lee, or an Emma to fill the longing that this novel surreptitiously uncovered in my soul? Did my own small collection of friendships seem not enough compared to the bond these four shared? And why not? Was it the way they supported one another or the way they alwaysmade time for one another? Or was it the way one could behave in a manner that was very unlovable and yet still remain loved?

At the risk of making a grand, sweeping gender statement, I’ll point out that some men seem to have categories of friends. They have work friends, friends for playing weekly pickup basketball games, golfing friends, and friends forced on them by a significant other. Seldom do they see these friends outside their category of identity, yet they would call them friends.

Many of the friendships women hold, however, seem to make their way beyond the circumstances that brought them together and meander into their lives through both the valleys and the peaks, eventually ending up in the women’s souls, where they can both restore and destruct. And yet, isn’t a real friendship one that would bring both the yin and the yang, so to speak? Is the multidimensional aspect of the relationship the very characteristic that makes it a true friendship?Would I have been so captivated and, yes, envious of the saving graces if their friendships contained no shadows?

History is rife with story upon story of love, commitment, bravery, loyalty, betrayal, and disappointment—all within friendships. And in our own personal histories, many of the same stories can be told Friendship is a relationship we desire and cultivate early in our development, whether we had an imaginary friend as a constant companion or we began the first day of school as a shy, pigtailed little girl inviting another to be our friend.

For a woman, the connection to friendship is innate and essential. It feels so vital to life and to living that the desire for it seems part of our fabric of being. Cicero said friendship “springs from nature rather than from need—from an inclination of the mind with a certain consciousness of love.”1 This is certainly true across generations and cultures. Early Chinese culture held women’s friendships as almost sacred. In her beautiful work of historical fiction Snow Flower and the Secret Fan, Lisa See educates her readers about sacred friendship practices.2 The Chinese women of this patriarchal culture committed themselves to very deep friendships, knowing there was substance and soul that could exist in no other relationships.

There were two types of soul friendships: sworn sisters and laotongs, which means “old same.” Sworn sisterhoods were groups of unmarried women who became friends.These sisterhoods dissolved at the time of marriage. A laotong relationship was between two girls from different villages.Many superstitions were observed before two girls would be found to be a match.They were usually the same age and both born in auspicious years, according to the tradition. The girls were bound together in lifelong friendship, in a ceremony that was nearly equivalent to a marriage ceremony in its commitments and gravity.The larger world only learned of the existence of this tradition of special friendships when, in a crowded train station at the height of China’s Cultural Revolution, a woman was detained as a suspected spy after

fainting. Authorities searched her belongings in an effort to identify her and found papers written in a language none could identify. Scholars were brought in to examine the writings, and they discovered that the elderly woman was not a spy after all; rather, her writings were in a secret language used only by women in the region of Yao. This language was a secret for more than a thousand years.

Sadly, most of the writings in nu shu have not survived over the years as they were either buried with the women at their death to accompany them to the other world or destroyed in the revolution. In the twentieth century, the nu shu language is all but extinct and no longer needed. But its existence and use discloses the depth of friendship and community among these women—and the universal, powerful longing for friendship that exists among us, the desire to be known and heard.

How do you know your friends, and how do you find them?Most of us look back on lives decorated with stories of friendships from the time we were young. There are the friends we hurried home from school to play with every day. After donning play clothes and perhaps wolfing down a snack, we’d join them for some clandestine adventure until we were summoned to dinner at dusk. There are the friends who gave us our social life when we were teenagers, inviting us to something somewhere that opened an entire new world of cliques, jealousy, loyalty, and, ultimately, resiliency. There are the friends of our early twenties, alongside whom we entered independence, straddling worlds of codependency and experimental autonomy. There are the friends who champion us through many of the celebrations and disappointments of adult life, from marriage and professional promotions to buying a first home and having children, along with a myriad of heartbreaks and losses.

And there’s every kind of friend in between. The friend you go to the ballet with; the friend you shop with—the one who talks you into a regrettable purchase every time; the one who will tell you what you want to hear and the one who has the courage to tell you what you don’t; the friend from whom you always get the latest news on everyone else; the one who will listen when you need to be heard and the one who will talk when you only have energy to listen. There’s the role model, the mentor, and the friend with whom you have a love-hate relationship.There are group and work friendships, friendships within a larger community, the “our children are best friends” and “our husbands are best friends” relationships.

If so many different types of connections are called friendships, do they all come from the same well, some single essence of friendship?What is it that creates a friendship? Is it social obligation, the fact that you wanted a large wedding party so the pictures would look better, necessity, or essential longing? And if it is longing, is the primary catalyst our longing for someone’s friendship or that person’s longing for ours? Do we need to know the answers to these questions to be a good friend or to have a fulfilling friendship—or am I simply overanalyzing that which just happens naturally?

My worn paperback copy of The Saving Graces placed back on my shelf of fiction between authors Fielding and Grisham, these were the questions I went looking to answer.

For centuries poets, authors, and song and screenplay writers have sought to define friendship—with results ranging from Aristotle’s conclusion that friendship is “a single soul dwelling in two bodies” to Ralph Waldo Emerson’s description of a friend as “a person with whom I may be sincere.”3

Certainly a distinction should be made between an acquaintance and a true friend. Is friendship simply companionship? For me, this is not the case. The Saving Graces taught me a narrower, even sacred definition of friendship.

What qualifies someone to be called your friend?

I read a sweet story by F.W. Boreham about a little boy plagued by nightmares.4 Rather than visions of sugarplums, a frightening tiger intrudes on the boy’s dreams. Night after night, the child wakes in fear, a cold sweat, and a rapidly beating heart. His parents are concerned (and probably lacking sleep if the boy is crawling into bed with them each night), and they send him to a child psychologist. After listening to the boy recount his dreams, the psychologist gets an idea. He tells the child, “The tiger visiting you is actually a good tiger. He wants to be your friend. So next time the tiger appears in your dream, simply put your hand out to shake his paw and say, ‘Hello, old chap!’ ”

And so, the story goes, that very same night the boy asleep in his bed suddenly becomes restless. He thrashes about in his bed, sweating and crying out in his sleep, until a small hand, partly hidden by cotton pajamas, suddenly juts out from the covers, followed by a sleepy little voice saying, “Hello, old chap!” Thus he made friends with the tiger.

That story makes me smile, and I suppose, partly, this is because of the old English language that scripts a little boy using amusing terms like “old chap.” But is that how it’s done? Is mere familiarity how friendships are forged? Does simply banishing the title of stranger make way for friendship? Or is something more required?

Perhaps it is the banishing of danger.The reason the tiger trick worked on the little boy’s nightmares was that it removed the danger.Maybe that works inmaking friends too. Maybe, beyond simple introductions so thatwe are no longer strangers, we enter a shared space with a person that we hope is safe—safe for us to be ourselves and to be real.

What creates that safe space? Is it simply shared interest or geography? Is friendship born in similar goals or experiences? What about behavior? If two people act in a certain way toward each other, are they friends? If so, then what does friendship look like?

As I thought about how art imitates life, and ever a lover of art, paintings, literature, poetry, films, and music, I mulled the characteristics of friendship and the numerous recent pictures of friendship, specifically women’s friendships.When I interact with these different mediums, something in them resonates with me, something that moves me, and I stop and notice.Whether it’s a tearjerker movie, a painting whose brush strokes create a gentle gesture, or lyrics so poignant, art inspires me to pay attention to what is within myself.

In the 1980s film The Four Seasons, the opening scene depicts three couples going away for a few days in the spring. Toasts and speeches characterize this holiday together, and the couples celebrate the depth of their friendships.We learn that the men were introduced to each other after the women became friends. The following season, summer, one friend is missing. During the previous few months, one couple has divorced and a cute young girlfriend has joined the circle to now complete the six. I couldn’t help but wonder what happened to the wife. Why is she eliminated from the circle of friends? And if the

women were the original friends, why have they agreed to oust her from the group?Why doesn’t the divorced couple at least get joint custody of their friends?

Throughout the movie’s four seasons, we see what each friend brings to the circle of friendship. We see the idiosyncrasies, bad habits, and selfishness, but also the commitment to one another through all the terrain in each season of friendship. And when one woman cries out in sheer frustration that, in spite of it all, she needs her friends and always will, we feel the truth of her statement reverberate through us.This was a climactic exclamation aftermonths of tension created by selfishness, lack of awareness, and judgment between the friends.

But yes, in spite of the hurts our friendships can cause, we need them, we want them.

Growing up I adored reading and seeing films of Anne of Green Gables. I still do. Anne, an imaginative and precocious orphan, comes to live with an aging pair of siblings, neither of whom has ever married. Marilla, a salty, no-nonsense woman, doesn’t have either the understanding or the patience for Anne’s emotions and antics. Matthew, her brother, is a soft-spoken and kindhearted man, though timid too.When Anne arrives in Avonlea and is invited to become part of Matthew andMarilla Cuthbert’s family, she sets out to make a friend. But Anne isn’t looking for just any acquaintance; rather, she is in search of a “kindred spirit,” a “bosom friend.”

“A—a what kind of a friend?”Marilla asked her, puzzled.

“A bosom friend—an intimate friend, you know—” Anne replied, “a really kindred spirit to whom I can confide my inmost soul. I’ve dreamed of meeting her all my life. I never really supposed I would, but so many of my loveliest dreams have come true all at once that perhaps this one will too. Do you think it’s possible?”

Later, after learningmore about a potential bosom friend, Anne adds one more requirement: “Oh, I’m so glad she’s pretty.Next to being beautiful oneself—and that’s impossible in my case—it would be best to have a beautiful bosom friend.”5

With the unflinching honesty of a child, Anne expresses what we all secretly desire: a best, kindred-spirit kind of friend. The older we get, the more reluctant we are to ask for what we want or need, but Anne does so unabashedly. And in her eyes, her friendship with Diana ismade even better when her new friend is someone that Anne herself is convinced she could never be. Could it be that we go in search of friends who embody something we wish we were or long to be?

Recenzii

“Friendships take years to cultivate yet can be lost in a matter of minutes. Sarah Zacharias Davis deftly explores the complex terrain of that human bond, explaining why so many of us long to be known and how important it is cultivate at least a few faithful people who will stand beside us the rest of our lives.”

–Julia Duin, religion editor for The Washington Times and author of Quitting Church: Why the Faithful are Fleeing and What to Do About It

“Sarah’s words could not come at a better time. Too many of us have allowed our female friendships to slip on the priority scale and this book is the perfect reminder of the essential, beautifully ordained connection between women. Reading and relishing her words, I recalled with rich nostalgia the formative friendships of my childhood and emerged from the pages with a fresh perspective and heightened appreciation for the special women in my life today. This book reads like the voice of a friend, intimate and true.”

–Kristin Armstrong, contributing editor for Runner’s World magazine and author of four books, including Happily Ever After: Walking with Peace and Courage Through a Year of Divorce and Work in Progress: An Unfinished Woman’s Guide to Grace

“The Friends We Keep is a true and tender testimony to the joys and struggles we women experience in our friendships with one another. As I read I found myself nodding in agreement, and sometimes tearing up in remembrance. We don’t always get it right, but we need each other–and there is deep satisfaction to be found in the relationships we forge. I loved Sarah’s book and recommend it to anyone who seeks to know (or find) her truest friends.

–Leigh McLeroy, author of The Beautiful Ache and Treasured

–Julia Duin, religion editor for The Washington Times and author of Quitting Church: Why the Faithful are Fleeing and What to Do About It

“Sarah’s words could not come at a better time. Too many of us have allowed our female friendships to slip on the priority scale and this book is the perfect reminder of the essential, beautifully ordained connection between women. Reading and relishing her words, I recalled with rich nostalgia the formative friendships of my childhood and emerged from the pages with a fresh perspective and heightened appreciation for the special women in my life today. This book reads like the voice of a friend, intimate and true.”

–Kristin Armstrong, contributing editor for Runner’s World magazine and author of four books, including Happily Ever After: Walking with Peace and Courage Through a Year of Divorce and Work in Progress: An Unfinished Woman’s Guide to Grace

“The Friends We Keep is a true and tender testimony to the joys and struggles we women experience in our friendships with one another. As I read I found myself nodding in agreement, and sometimes tearing up in remembrance. We don’t always get it right, but we need each other–and there is deep satisfaction to be found in the relationships we forge. I loved Sarah’s book and recommend it to anyone who seeks to know (or find) her truest friends.

–Leigh McLeroy, author of The Beautiful Ache and Treasured

Descriere

During a particularly painful time in her life, Davis learned how delightful--and wounding--women can be in friendship. "The Friends We Keep" is the author's thoughtful account of the importance of successfully navigating friendship.