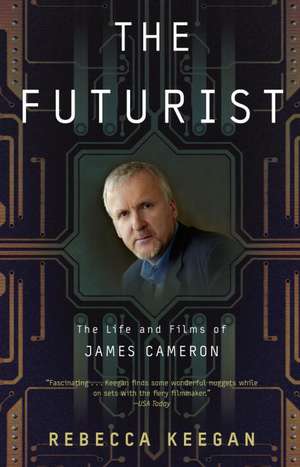

The Futurist: The Life and Films of James Cameron

Autor Rebecca Keeganen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2010

With cooperation from the often reclusive Cameron, author Rebecca Keegan has crafted a singularly revealing portrait of the director’s life and work. We meet the young truck driver who sees Star Wars and sets out to learn how to make even better movies himself—starting by taking apart the first 35mm camera he rented to see how it works. We observe the neophyte director deciding over lunch with Arnold Schwarzenegger that the ex-body builder turned actor is wrong in every way for the Terminator role as written, but perfect regardless. After the success of The Terminator, Cameron refines his special-effects wizardry with a big-time Hollywood budget in the creation of the relentlessly exciting Aliens. He builds an immense underwater set for The Abyss in the massive containment vessel of an abandoned nuclear power plant—where he pushes his scuba-breathing cast to and sometimes past their physical and emotional breaking points (including a white rat that Cameron saved from drowning by performing CPR). And on the set of Titanic, the director struggles to stay in charge when someone maliciously spikes craft services’ mussel chowder with a massive dose of PCP, rendering most of the cast and crew temporarily psychotic.

Now, after his movies have earned over $5 billion at the box office, James Cameron is astounding the world with the most expensive, innovative, and ambitious movie of his career. For decades the moviemaker has been ready to tell the Avatar story but was forced to hold off his ambitions until technology caught up with his vision. Going beyond the technical ingenuity and narrative power that Cameron has long demonstrated, Avatar shatters old cinematic paradigms and ushers in a new era of storytelling.

The Futurist is the story of the man who finally brought movies into the twenty-first century.

Preț: 106.64 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 160

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.41€ • 21.36$ • 16.88£

20.41€ • 21.36$ • 16.88£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307460325

ISBN-10: 0307460320

Pagini: 283

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 0307460320

Pagini: 283

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

As a Hollywood-based contributor to Time magazine, Rebecca Keegan has profiled actors and directors including Francis Ford Coppola, Will Smith, and Penelope Cruz. She has written trend stories about 3-D, horror auteurs, and fanboy culture and penned play-by-plays of the Oscars, the Sundance Film Festival, and Comic-Con. She spent seven years in Time’s New York bureau covering breaking news stories such as 9/11, Osama bin Laden, and the Catholic Church sex-abuse crisis. She has appeared on CNN, Fox News, MSNBC, and NPR. She lives in Los Angeles with her husband.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

1.

A Boy and His Brain

The Beginning of the End

The end of the world was coming. And he was eight. That’s when James Cameron found a pamphlet with instructions for building a civilian fallout shelter on the coffee table in his family’s living room in Chippawa, Ontario, a quaint village on the Canadian shore of Niagara Falls. It was 1962, the year of the Cuban missile crisis, and Philip and Shirley Cameron felt they had reason to be concerned about the bomb—the Camerons lived just a mile and a half from the falls, a major power source for communities on both sides of the international border. But for their oldest son, discovering the brochure was a life-changing epiphany. Prior to that moment, the boy’s only real care in the world had been getting home on his bike before the streetlights flickered on, the family rule. “I realized that the safe and nurturing world I thought I lived in was an illusion, and that the world as we know it could end at any moment,” Cameron says. From that time on, he was fascinated by the idea of nuclear war, his fears fueled by the apocalyptic scenarios depicted in the science-fiction books he devoured at night, reading under his blanket with a flashlight. He may have been the only kid at his school to find the duck-and-cover bomb drills neither funny nor stupid. “Was this crazy or just a heightened awareness of truth?” Cameron wonders. “As the world turned out so far, it was a bit paranoid. But there’s still plenty of time to destroy ourselves.”

The pensive eight-year-old boy would grow up to tell vivid stories about worlds ending, from a machine-led war in 2029 to an unsinkable ship’s descent into the deep in 1912. Each James Cameron movie is a warning against his darkest childhood fears and a kind of how-to guide for living through catastrophe with humanity and spirit intact. His own story begins with a long line of troublemakers.

Philip and Shirley

Cameron’s great-great-great-grandfather, a schoolteacher, migrated from Balquhidder, Scotland, to Canada in 1825. “He was a bit of a free thinker. He didn’t like the king,” explains Philip, a plainspoken electrical engineer, understating things a bit. The Cameron clan is one of Scotland’s oldest, a family of notoriously fierce swordsmen who were leaders in the Jacobite uprisings, the bitter Anglo-Scottish religious wars of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Some were executed for treason, others exiled. Philip Cameron’s branch ended up on a farm near Orangeville, Ontario, about fifty miles northwest of Toronto, where he attended a one-room school before following work north as a nickel miner to earn the money to enter the University of Toronto in 1948. “Pops is very male, strong. He was always bigger than everybody even though he wasn’t bigger than everybody,” says the Camerons’ youngest son, John David. “He was the guy you didn’t want to mess with. If it took you two turns of the wrench, it took Dad a half.”

In high school Philip met Shirley Lowe, a slim, blonde-haired, blue-eyed dynamo who drove stock cars in the Orangeville powder-puff derby and won a countywide award for her war bond painting of a city in flames. “Do you want this to happen?” it asked ominously in red paint. While a mother with three kids under age eight, Shirley would join the Canadian Women’s Army Corps, happily trooping off on weekends in fatigues and combat boots to assemble a rifle while blindfolded and march through fields in the pouring rain. She kept up her painting, in oils and watercolors, and one night a week she attended an adult education course in a subject of interest, such as geology or astronomy. “I did those things for me and nobody else,” says Shirley, who professes bewilderment that she might be the inspiration for the gutsy maternal heroines in movies like The Terminator and Aliens. “I don’t know why Jim thinks I’m so self-reliant,” Shirley adds with a shrug, her blue eyes sparkling. Philip looks up from the dining table in their Calabasas, California, home, clearly amused by his wife of fifty-seven years. “Well, you are,” he says wryly. Shirley is creative, impulsive, and fiery, Philip stoic, analytical, and precise. “It’s tough to be diplomatic with stupid people,” he confesses. Their wildly different dispositions would combine uniquely in their son, who became equal parts calculating gearhead and romantic artist.

When their first child was born, the Camerons were living in an apartment in Kapuskasing, a cold, remote company town in northern Ontario where Philip worked as an engineer at the local paper plant. Shirley had trained as a nurse in Toronto but was now a somewhat restless homemaker. On August 16, 1954, James Cameron arrived in the world one month late and screaming, an image Hollywood studio executives will have no trouble picturing. Because he was their first child, the Camerons didn’t know there was anything unusual about Jim. When he strode into a doctor’s office at eighteen months old, extended his hand, and said, “How do you do, doctor?” they learned their son was a little precocious.

Chippawa

When Cameron was five, Philip’s job took the family to Niagara Falls, and from there they moved to a comfortable split-level in Chippawa, where they would live until 1971. The family kept growing— next came Mike, Valerie, Terri, and John David. The Cameron kids freely roamed the shores of Chippawa Creek, which is actually, by non-Canadian standards, a rushing river. There were fishing trips and daredevil hikes above the deep gorges. Cameron once slipped off an algae-covered board down a hundred-foot cliff, catching a tree limb and scrambling back up, a misadventure he never shared with his parents. “What happens on the hike stays on the hike,” he says. He became a tinkerer, building and experimenting, often with his brother Mike. They made go-karts, rafts, tree houses. A favorite toy was the Erector Set, which Cameron had earned by selling greeting cards. (Shirley paid off the neighbors to buy them—mothers can keep secrets, too.) He used the Erector Set to construct Rube Goldberg contraptions for dispensing candy and Coke bottles. Once he built a mini bathysphere with a mayonnaise jar and a paint bucket, put a mouse in the jar, put the jar in the bucket, and lowered the bucket off a bridge to the bottom of Chippawa Creek. When he pulled it back up, the mouse was still alive, but probably not without having had a good shock. Another proud engineering milestone was the Summer Vacation Trebuchet, a siege engine Cameron constructed out of an old hay wagon at his grandparents’ farm near Orangeville and used to launch twenty-pound rocks at spare-lumber targets he had dragged into the cow pasture.

The Cameron boys’ handiness with tools was not always constructive. When some neighborhood kids stole their toys, Jim and Mike visited the lead suspects’ tree house and sawed through the limbs. When the juvenile criminals climbed up to their woody retreat, it toppled to the ground. “That one they got in trouble for,” says Shirley, nodding. “You don’t do things where people can get hurt.” Philip was the stern disciplinarian in the family, usually able to get his point across in few words. “My dad used to warn me, ‘If you mess up I’ll take you to the woodshed,’” remembers John David. “I was pretty confident I knew the house, and I didn’t think we even had a woodshed. The threat was worse than any actual act.”

Early on, Cameron demonstrated a knack for assembling large groups in service of his own goals. When her oldest son was about ten, Shirley noticed his younger siblings and several neighborhood children streaming into her side yard carrying scraps of wood and metal. “I said, ‘What are you gonna do with all this junk?’” Shirley recalls. “Jim said, ‘We’re gonna build something.’” When Shirley checked on the project a couple of hours later, the kids had constructed an airplane. “Guess who was sitting in it being pulled?” Cameron was very good at telling people what to do. He took it upon himself to keep his younger siblings in line when the family went out to dinner. The oldest boy would fold his hands on the table and start twiddling his thumbs, a cue to the little ones to follow and not to grab the salt and pepper shakers.

Shirley encouraged her son’s artistic side. At his request, some Saturdays they traveled eighty miles to the Royal Ontario Museum, where Cameron pulled out his sketchbook to draw helmets and mummies. “Everything I saw and liked and reacted to I immediately had to draw,” he says. “Drawing was my way of owning it.” He created his own comic-book versions of movies and TV shows he liked, from pirates inspired by the 1961 Ray Harryhausen fantasy Mysterious Island to spaceships he saw on the first season of Star Trek in 1966. He easily won all the local design contests—to paint a mural on the Seagram Tower at Niagara Falls or the bank windows at Halloween. At age fourteen, he painted a Nativity scene for the bank for one hundred dollars, enough to buy Christmas presents for his parents and siblings.

The Cameron kids are an intense bunch, biochemically turbo-charged. Close in age and temperament, Jim and Mike were sometimes coconspirators, sometimes rivals, often both at once. Mike would grow up to be an engineer like his father, building the sophisticated filmmaking and diving technologies used on The Abyss, Titanic, and his older brother’s documentaries. Both bright and convinced of their own opinions, the two oldest Cameron boys are a technically potent and often explosive duo. They could turn a theoretical conversation on space travel into a rowdy brawl. “When they’d mix, there would be fireworks, good and bad,” says their youngest brother, John David, who likens the Cameron family dynamic to “Japan before warfare; everybody’s got their own systems.”

Dinner was served at 6:00 p.m. at the Cameron house every night and timed with military precision. “I make good carbon,” Shirley says of her culinary efforts. “I burn things.” Her sons talk glowingly of her chili and pot roast but say that it was best when Shirley didn’t bring her adventuresome spirit into the kitchen. At a certain point, dinner with the Camerons would become a contact sport. “The more of the family that gets together, the more chaotic and loud and bright and crescendoed it gets, from who gets the goddamned dish,” John David says. “There will always be a moment when somebody says something that shouldn’t have been said. It’s priceless. But it’s participatory. If you sit idly by, you’ll get chewed on.”

From the Hardcover edition.

A Boy and His Brain

The Beginning of the End

The end of the world was coming. And he was eight. That’s when James Cameron found a pamphlet with instructions for building a civilian fallout shelter on the coffee table in his family’s living room in Chippawa, Ontario, a quaint village on the Canadian shore of Niagara Falls. It was 1962, the year of the Cuban missile crisis, and Philip and Shirley Cameron felt they had reason to be concerned about the bomb—the Camerons lived just a mile and a half from the falls, a major power source for communities on both sides of the international border. But for their oldest son, discovering the brochure was a life-changing epiphany. Prior to that moment, the boy’s only real care in the world had been getting home on his bike before the streetlights flickered on, the family rule. “I realized that the safe and nurturing world I thought I lived in was an illusion, and that the world as we know it could end at any moment,” Cameron says. From that time on, he was fascinated by the idea of nuclear war, his fears fueled by the apocalyptic scenarios depicted in the science-fiction books he devoured at night, reading under his blanket with a flashlight. He may have been the only kid at his school to find the duck-and-cover bomb drills neither funny nor stupid. “Was this crazy or just a heightened awareness of truth?” Cameron wonders. “As the world turned out so far, it was a bit paranoid. But there’s still plenty of time to destroy ourselves.”

The pensive eight-year-old boy would grow up to tell vivid stories about worlds ending, from a machine-led war in 2029 to an unsinkable ship’s descent into the deep in 1912. Each James Cameron movie is a warning against his darkest childhood fears and a kind of how-to guide for living through catastrophe with humanity and spirit intact. His own story begins with a long line of troublemakers.

Philip and Shirley

Cameron’s great-great-great-grandfather, a schoolteacher, migrated from Balquhidder, Scotland, to Canada in 1825. “He was a bit of a free thinker. He didn’t like the king,” explains Philip, a plainspoken electrical engineer, understating things a bit. The Cameron clan is one of Scotland’s oldest, a family of notoriously fierce swordsmen who were leaders in the Jacobite uprisings, the bitter Anglo-Scottish religious wars of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Some were executed for treason, others exiled. Philip Cameron’s branch ended up on a farm near Orangeville, Ontario, about fifty miles northwest of Toronto, where he attended a one-room school before following work north as a nickel miner to earn the money to enter the University of Toronto in 1948. “Pops is very male, strong. He was always bigger than everybody even though he wasn’t bigger than everybody,” says the Camerons’ youngest son, John David. “He was the guy you didn’t want to mess with. If it took you two turns of the wrench, it took Dad a half.”

In high school Philip met Shirley Lowe, a slim, blonde-haired, blue-eyed dynamo who drove stock cars in the Orangeville powder-puff derby and won a countywide award for her war bond painting of a city in flames. “Do you want this to happen?” it asked ominously in red paint. While a mother with three kids under age eight, Shirley would join the Canadian Women’s Army Corps, happily trooping off on weekends in fatigues and combat boots to assemble a rifle while blindfolded and march through fields in the pouring rain. She kept up her painting, in oils and watercolors, and one night a week she attended an adult education course in a subject of interest, such as geology or astronomy. “I did those things for me and nobody else,” says Shirley, who professes bewilderment that she might be the inspiration for the gutsy maternal heroines in movies like The Terminator and Aliens. “I don’t know why Jim thinks I’m so self-reliant,” Shirley adds with a shrug, her blue eyes sparkling. Philip looks up from the dining table in their Calabasas, California, home, clearly amused by his wife of fifty-seven years. “Well, you are,” he says wryly. Shirley is creative, impulsive, and fiery, Philip stoic, analytical, and precise. “It’s tough to be diplomatic with stupid people,” he confesses. Their wildly different dispositions would combine uniquely in their son, who became equal parts calculating gearhead and romantic artist.

When their first child was born, the Camerons were living in an apartment in Kapuskasing, a cold, remote company town in northern Ontario where Philip worked as an engineer at the local paper plant. Shirley had trained as a nurse in Toronto but was now a somewhat restless homemaker. On August 16, 1954, James Cameron arrived in the world one month late and screaming, an image Hollywood studio executives will have no trouble picturing. Because he was their first child, the Camerons didn’t know there was anything unusual about Jim. When he strode into a doctor’s office at eighteen months old, extended his hand, and said, “How do you do, doctor?” they learned their son was a little precocious.

Chippawa

When Cameron was five, Philip’s job took the family to Niagara Falls, and from there they moved to a comfortable split-level in Chippawa, where they would live until 1971. The family kept growing— next came Mike, Valerie, Terri, and John David. The Cameron kids freely roamed the shores of Chippawa Creek, which is actually, by non-Canadian standards, a rushing river. There were fishing trips and daredevil hikes above the deep gorges. Cameron once slipped off an algae-covered board down a hundred-foot cliff, catching a tree limb and scrambling back up, a misadventure he never shared with his parents. “What happens on the hike stays on the hike,” he says. He became a tinkerer, building and experimenting, often with his brother Mike. They made go-karts, rafts, tree houses. A favorite toy was the Erector Set, which Cameron had earned by selling greeting cards. (Shirley paid off the neighbors to buy them—mothers can keep secrets, too.) He used the Erector Set to construct Rube Goldberg contraptions for dispensing candy and Coke bottles. Once he built a mini bathysphere with a mayonnaise jar and a paint bucket, put a mouse in the jar, put the jar in the bucket, and lowered the bucket off a bridge to the bottom of Chippawa Creek. When he pulled it back up, the mouse was still alive, but probably not without having had a good shock. Another proud engineering milestone was the Summer Vacation Trebuchet, a siege engine Cameron constructed out of an old hay wagon at his grandparents’ farm near Orangeville and used to launch twenty-pound rocks at spare-lumber targets he had dragged into the cow pasture.

The Cameron boys’ handiness with tools was not always constructive. When some neighborhood kids stole their toys, Jim and Mike visited the lead suspects’ tree house and sawed through the limbs. When the juvenile criminals climbed up to their woody retreat, it toppled to the ground. “That one they got in trouble for,” says Shirley, nodding. “You don’t do things where people can get hurt.” Philip was the stern disciplinarian in the family, usually able to get his point across in few words. “My dad used to warn me, ‘If you mess up I’ll take you to the woodshed,’” remembers John David. “I was pretty confident I knew the house, and I didn’t think we even had a woodshed. The threat was worse than any actual act.”

Early on, Cameron demonstrated a knack for assembling large groups in service of his own goals. When her oldest son was about ten, Shirley noticed his younger siblings and several neighborhood children streaming into her side yard carrying scraps of wood and metal. “I said, ‘What are you gonna do with all this junk?’” Shirley recalls. “Jim said, ‘We’re gonna build something.’” When Shirley checked on the project a couple of hours later, the kids had constructed an airplane. “Guess who was sitting in it being pulled?” Cameron was very good at telling people what to do. He took it upon himself to keep his younger siblings in line when the family went out to dinner. The oldest boy would fold his hands on the table and start twiddling his thumbs, a cue to the little ones to follow and not to grab the salt and pepper shakers.

Shirley encouraged her son’s artistic side. At his request, some Saturdays they traveled eighty miles to the Royal Ontario Museum, where Cameron pulled out his sketchbook to draw helmets and mummies. “Everything I saw and liked and reacted to I immediately had to draw,” he says. “Drawing was my way of owning it.” He created his own comic-book versions of movies and TV shows he liked, from pirates inspired by the 1961 Ray Harryhausen fantasy Mysterious Island to spaceships he saw on the first season of Star Trek in 1966. He easily won all the local design contests—to paint a mural on the Seagram Tower at Niagara Falls or the bank windows at Halloween. At age fourteen, he painted a Nativity scene for the bank for one hundred dollars, enough to buy Christmas presents for his parents and siblings.

The Cameron kids are an intense bunch, biochemically turbo-charged. Close in age and temperament, Jim and Mike were sometimes coconspirators, sometimes rivals, often both at once. Mike would grow up to be an engineer like his father, building the sophisticated filmmaking and diving technologies used on The Abyss, Titanic, and his older brother’s documentaries. Both bright and convinced of their own opinions, the two oldest Cameron boys are a technically potent and often explosive duo. They could turn a theoretical conversation on space travel into a rowdy brawl. “When they’d mix, there would be fireworks, good and bad,” says their youngest brother, John David, who likens the Cameron family dynamic to “Japan before warfare; everybody’s got their own systems.”

Dinner was served at 6:00 p.m. at the Cameron house every night and timed with military precision. “I make good carbon,” Shirley says of her culinary efforts. “I burn things.” Her sons talk glowingly of her chili and pot roast but say that it was best when Shirley didn’t bring her adventuresome spirit into the kitchen. At a certain point, dinner with the Camerons would become a contact sport. “The more of the family that gets together, the more chaotic and loud and bright and crescendoed it gets, from who gets the goddamned dish,” John David says. “There will always be a moment when somebody says something that shouldn’t have been said. It’s priceless. But it’s participatory. If you sit idly by, you’ll get chewed on.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"A fascinating journey into the mind of the master, as meticulously detailed and entertaining as Cameron's greatest works. A humanizing and warm look into the man behind the machinery. Rebecca Keegan reveals sides of Cameron never before seen by his public and gives us an intimate, warm portrait of a mysterious genius. A must read for fans and filmmakers alike. This biography will become one of the bibles for all aspiring filmmakers." --ELI ROTH, director and actor

"An empathetic and incisive portrait of the most authentic visionary - and genuine renaissance man - in the movie business." --MARK FROST, co-creator of Twin Peaks

"What a pleasure -- a writer who can really write and a subject we really need, as well as want, to know more about." —JOE MORGENSTERN, film critic, Wall Street Journal

From the Hardcover edition.

"An empathetic and incisive portrait of the most authentic visionary - and genuine renaissance man - in the movie business." --MARK FROST, co-creator of Twin Peaks

"What a pleasure -- a writer who can really write and a subject we really need, as well as want, to know more about." —JOE MORGENSTERN, film critic, Wall Street Journal

From the Hardcover edition.